Being is not only about thinking

Interview with a member of “Slavs and Tatars”

25/09/2018

The name of the individual member of the “Slavs and Tatars” – one of the most notorious guests of this year's Survival Kit – who had come to Riga during the opening days of the festival is probably not at all hard to find out for anyone who wants to. But, as he insisted many times during our conversation, his name is not important, because “art is already too often about personalities and not about ideas”. “Slavs and Tatars”, an international artist and researcher group founded in 2006, is not strictly anonymous, but its individual members – whose line-up is also constantly fluctuating – choose to better keep their personal identities in the shadow in order not to distract the gaze from the ideas and activities of the group itself.

“Slavs and Tatars” is a rather unique and mobile group who work in cycles that are defined by themselves and by their interests. Sometimes these cycles of work manifest in artworks, sometimes – in books and other publications. All their archive is freely accessible online, as uncovering and spreading an unknown knowledge has been the group's goal since the beginning. They use the region “between two walls – the Berlin Wall and the Great Wall of China” as a “platform that allows them to question some assumptions of the Enlightenment”. It is hard to question the Enlightenment from the geographical centres, because “centres are always rotten. Things get interesting in the borders of empires, borders of knowledge. Borders are interesting in terms of identity”.

These borders of empires and knowledge are indeed what drives the various work cycles of “Slavs and Tatars”, and for this year's Survival Kit they had chosen to show some of the results of their interest in transliteration and the alphabets in their written form, and how alphabets, often conceived as innocent linguistic elements, are in fact tools for empire building. Right before the guest member of the group gave the local audience a lecture-performance on this subject, we sat down for a tea to have an unfortunately short, but rather lively conversation.

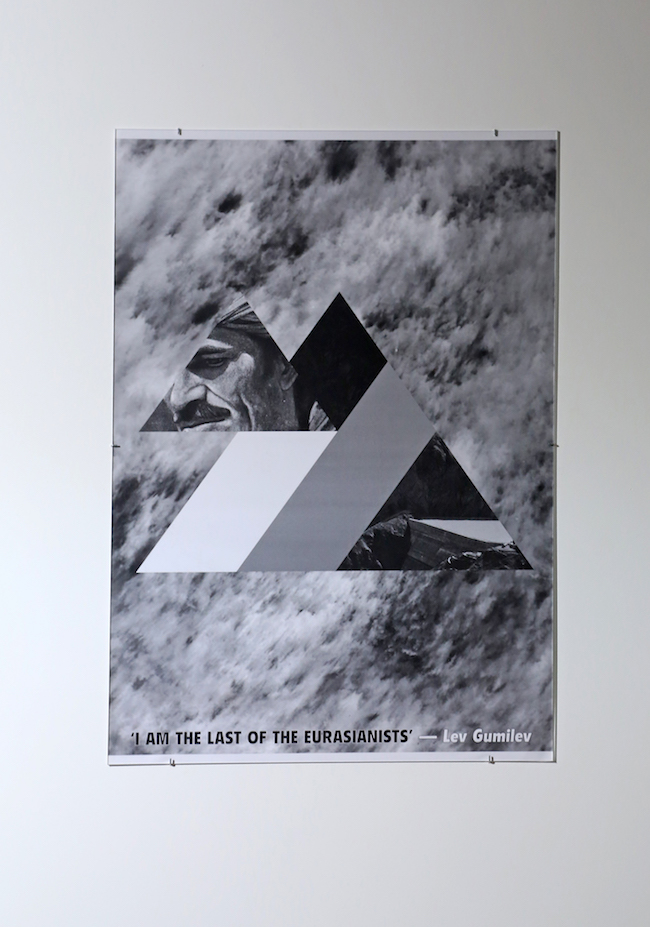

Slavs and Tatars, Last of the Eurasianists, 2008. Photo: Margarita Ogoļceva, Latvian Centre for Contemporary Art, 2018, screenprint on paper; 100×70 cm

Arterritory: Slavs and Tatars define themselves as a group of artists who concentrate on the region between two walls – the Berlin Wall and the Great Wall of China. It's like one third of the world. Is there anything at all common to this vast area?

Slavs and Tatars: Sure, there is something absurd about this. We deliberately chose a region which is way too big to be homogenous. You cannot say anything singular about such a big region. But, honestly, I think it's still the most interesting artistic gesture we've done thus far. Choosing such a large region shows, first of all, the humour in our work. It's a gesture of not taking ourselves too seriously. Choosing such a region goes against the idea if specialization, and we really are very much against it. We are against specialization of knowledge, for us knowledge is much more interesting when it is more lateral, you know? More vertical. But also... We often give lectures – like tonight. We have two or three of those every month, around the world. And people assume that we're some sort of specialists of this region, but, again – how can you possibly specialize on such a large region? We are not experts, and we are not even pedagogues. The idea of pedagogy assumes that one person knows and the other person doesn't know.

One person leads.

Yes, exactly. But we initially started as a book club, and in a book club there is no leader – it's sharing together. And it's one of the things that people often overlook – instead of being specialists, we have actually devoted ourselves to this region because we don't know it. In art world, people – and especially groups of artists – usually devote themselves to things they already know. Even here, at Survival Kit, if you look at the books that are presented and being sold, you see that those are the same old people upfront – Guy Debord, Boris Groys, Barthes etc. It's the names we all know. The art world is full of this kind of self-referential speaking between the same people. None of our books ever mention any of these people. Don't get me wrong – we've read them all. But we don't see the point in citing someone you've already read. What's the point? For me, when I'm reading, I'm much more interested in things I don't know. We started “Slavs and Tatars” to try to seek the kind of knowledge that is not being taught in universities. Everywhere in the world – be it Moscow, Tehran or New York – in the universities, they have the same editorial approach. That's sad. I don't think it’s conspiracy, it's just a kind of consolidation, a kind of lazy thinking. Well, let's say it's all an Enlightenment form of knowledge. It starts with Descartes and then it goes on and on, blah, blah, blah, in one straight succession. But there should be as many bodies of knowledge as there are places of knowledge, you know? Whether it's pre-modern knowledge or pagan knowledge, of theosophy, or anti-Enlightenment thinking... Why is it all one lineage?

Well, I suppose because it is widely believed that the inferences that the Enlightenment arrived at are universal. That cogito, ergo sum is equally true in Holland, and in Iran, and in Japan.

But we also have to understand that the results of that “enlightenment” are things like colonialism and genetically modified foods, and environmental disaster that we're living in now. It's that idea of putting the human first. And, by the way, I don't believe in cogito, ergo sum. I believe that sum, ergo cogito is at least equally important. Being is not only about thinking!

Ok.

There's a metaphysical being, a kind of being which is phenomenological. As much as there is a rational being. It's not one or the other. But Enlightenment really said that the mind is first. And that's why... You know, now people in the West are starting to understand all this Ayurvedic medicine, and the importance of stomach... It's starting, right? But people in India have known that for thousands of years! They have known that this (Pointing to stomach.) is just as important organ as this (Pointing to head.), but we have been focusing on the latter for 600 years and thought that all else is nonsense. But now we realize that actually no, this is also important! It's not one or the other.

But I guess we very quickly reeled away from my first question.

About things common in this region? Alright. I can perhaps name some micro-phenomena. One might be that generally across this region you don't split dinner bills.

(Laughs.)

Right? It's true! For me, one of the most depressing things in the world that you see in the West is, like, six people having dinner and then one of them saying – oh, I didn't have that one glass of wine, so I'm going to pay less. It's the most depressing form of humanity. Splitting those bloody twenty cents less or more. In our region, that generally doesn't happen. But it happens in the West. What else? (Thinks.) Well, yeah, in general, there has been less Enlightenment legacy in our region. That manifests in, for instance, a kind of still surviving superstitious-slash-mystical approach to plants, you know, grandmother's secret knowledge of herbal medicine etc. That is not scientific, but it's not all nonsense either. This is something you find in the Baltics, in Russia, in Poland. And what's especially interesting about Eastern Europe for me is that Eastern Europe was the first “orient”. You know, before all these European countries went and screwed Africa and Middle East, the first time they took something as “orient” was when they met Slavs and Balts, and...

You mean, during crusades? Or earlier?

A little later, actually. It really happened when Rousseau and Voltaire argued about, like, who is more civilised – the Poles or the Russians? Those were the first “wild” people, you know. And even the Nazis, they had all these theories that Slavs were lesser people, and that's why they were good dancers – because they were mixed with other races, so that they almost had bodies of black people, but in white skin. Such crazy race theory stuff.

I've heard that today's Neo Nazis in the West regard Slavs much more highly, being very influenced by Putin's alpha figure.

Yes, of course, and Putin himself has played enough with them. But in reality, of course, Russia is a very diverse country, and a country that was familiar with Islam long before the West. Many people believe that after 9/11, when U.S. started it's “war on terror”, Russia had a chance – and missed it – to show the world that there are alternative ways to coexist. Islam is deeply integrated in Russia's culture; in fact, there are some people who believe that Islam came to Russia even before Christianity, which did so in the 10th century. I believe that has always been Russia's strength – being both the West and the East. It's not only Western, it's not only Eastern. Of course, it's a geopolitical advantage, but it's also an intellectual advantage. It could use it if it were more honest about it, and not so cynical about it. But, of course, Russia's failing is that it wants to be Western so badly.

So, not messing with the dinner bills, herbal medicine... Anything else?

(Laughs.)

I would add picking mushrooms.

Right, it's starting now, isn't it?

Yes, it's the season. When Westerners find out about this phenomena, they often freak out, because they can't believe every regular person here knows which mushrooms are edible and which are not. But perhaps there are some “larger” issues as well?

Um... I think that something common to our region is an idea, or a sense that ancient history is as important as the recent history. That something that happened 4000 years ago is as important as something that happened 40 years ago. I have a sense that the more Westwards you go, the more amnesiac people become about the ancient history. That's past, that's done.

Slavs and Tatars, Kidnapping Mountains (Over-Here), 2009. Photo: Margarita Ogoļceva, Latvian Centre for Contemporary Art, 2018, screenprint on paper; 176×120 cm

Really? I think people everywhere in the West still consider Ancient Greece and its heritage to be very important.

Yeah, but that's a lie. It's fiction.

What do you mean?

This culture came to us mostly through Islam. There was no direct link. I was taught this nonsense all my life, in my Western education. That America is a direct descendant of Greek ideals and so on. That's nonsense. Even the idea that Europeans are descendants of Greeks and Romans is nonsense. It's a fantasy.

But we should distinguish between the overall popular awareness of the ancient history as something important and the narrower, scholastic approach to its continuity.

But this idea of continuity is a problem. Certain Greek ideals of society or ethics, or whatever didn't exist in a straight lineage from the Hellenic world to the founding of European societies. European societies went against these ideas for most of their history. And I would even argue that they go against them today. But for some reason it's how we like to present ourselves. It's the same as in Iran, where they are obsessed with Ferdowsi and the Book of Kings – you know, the kind of Iliad of the Persian literature. But that was actually written in and about the part of Iran which today is Afghanistan. It's about the invasion of these regions and not at all what Iran is today.

Ok, but let's stick to the idea that in your region of interest people consider the ancient history as equally important. How exactly does that unfold?

Well, I'll give you an example. When I was first living in Russia, which was in the 90-ies, during Yeltsin, people would talk about political issues and mention Ivan the Terrible in the same breath as they would mention Yeltsin. It doesn't qualify for judgement, it's not something good or bad, but there is a kind of helplessness in the face of history. The sense that you will fail, a defeatism. That history will always beat you, but you will try regardless. There is not that sort of positivism, which is a very Anglo-American idea, the idea that I can do this. I can do this. I am in charge of my life. I have agency.

The idea of progress?

Yeah, the idea that things get better. I don't believe things get better. If things get better, then how do you explain that in the 16th and 17th century in Poland and Lithuania you had more Muslim representatives in an elected government than you have in any European country today? Bloody 400 years ago. Is that progress? I don't know. Even the idea of modernity, which has allegedly brought us so many new things... I don't think that a modern man, a man from the 20th century, is essentially different from a man of the previous centuries. In the same way that Internet has not changed who we are. That's not something that you find very commonly said. It's considered that we're living in a kind of paradigm shift today, with the Internet. Or that somehow what Durkheim and Marx, and Freud, and Weber, whatever they all said, you know, that industrialization and science brought modernity, and that we don't need tradition and faith anymore... I don't believe that. I believe that we need tradition and we need faith. The question is – what kind of faith? In fact, one of our biggest failings in our idea of a political society today is that people like yourself and myself look down upon people of faith, we say that they are the ignorant ones...

I don't.

Ok, not you and me literally. But, let's say, generally in our milieu, we consider that religion is something for the masses, that it's reactionary, it's right-wing. But it's our responsibility to make... To find a kind of progressive idea within this idea of faith.

Wait, why? We do we need it?

Because... (Thinks.) If you look at... Perhaps first I could give a strategic, a pragmatic, almost a cynical answer. If you look at the examples of successful civil disobedience in the 20th century... Let's say, three examples – Martin Luther King, Ghandi and the fall of communism. Religion played a huge role in all three of those. The way we've presented them to ourselves has been kind of secular. But King was not a black secular leader, he was a Baptist who had heavily invested in his religion.

So you would say there is a correlation between successful disobedience and the presence of faith.

It's not only about correlation... We need all the tools we can get when fighting injustice. And, so, to ignore something that has been a part of human history for as long as we know, and to put it aside and to quarantine it is like using only half... You know, it's counter-intuitive. We tend to think the opposite way- that religion has actually contributed to our injustice. But it has actually liberated us as much as anything. After all, religion and faith is a body of knowledge that we can either ignore, that we can fight against or that we can use for our advantage – to advance beliefs and ideals that we believe in.

Alright, but that's the pragmatic answer.

It's the pragmatic answer.

Is there another answer?

From a more philosophical perspective, I think that it's important to have other forms of knowledge that are not so focused on analytical faculty. And this knowledge can be gnostic, or it can be a spiritual knowledge of a different tradition... And even if we look at certain figures who belong to the Western philosophical canon – I don't believe that you can understand, for instance, Hegel, Heidegger or Deleuze purely analytically. There's other parts of it. And there's just so many... Well, for instance, one thing we have recently done, we just published a book on a gentleman named Hamann...

You mean the philosopher?

Yes.

He used to live in Riga for a short while. We have a short street named after him over the river.

Oh, really? Well, it makes sense, the Berens family, who sponsored him, lived here in Riga... He's actually a super interesting guy. You know, he was friends with Kant, but he was basically the first anti-Enlightenment thinker. He decided to critique the Enlightenment, but from a very dual perspective which is very rare. He critiqued it from a Lutheran theology perspective, but also with a heavy mix of sexuality, with a lot of talk about genitalia. When I read the dedications of his works, for me it is clear that the guy was on another level, he was smoking something. I don't know what, but definitely something. So he would dedicate a work, for instance, “for the boredom of the public by a lover of boredom”. You know, in the 18th century, which is so obsessed with clarity, he was all about obfuscating. And then there was an episode when some intellectual attacked the letter “h” in German language and insisted that they should remove all the “h-es” when they are not pronounced. Remove from writing. And Hamann decides to do a defence for the letter “h”, and writes an apology to the letter “h”! And then, after that, he writes a follow-up – and apology to the letter “h”, but from the perspective of the “h” itself!

(Laughs.)

He puts himself in the position of the letter “h”. I mean, it's brilliant! It's super avant-garde for the 18th century. And my question when I read this is – why did nobody ever tell me about Hamann?! And it's not even me – most intellectuals in Germany don't know Hamann. Because, again, we have this consolidation of knowledge – he doesn't fit in our genealogy. Despite the fact that Kierkegaard called him “the greatest humourist of history”.

Yes, I suppose also here most people who drive by Hamann's street have no idea whom it is named after. And what exactly did you publish about him?

We just published a bi-lingual edition of some of his works and wrote a short introduction.

Oh, that's very nice. But to take a step back a little – I don't think you truly answered my question on what is the non-pragmatic answer to the question “why we need faith?”. If there is one.

I think it can work as a kind of tonic to the secular age we are living in now. And that's important. To make us more... Oh, all the words we are trying to use in this regard sound terrible! Even a word like “holistic”. But “holistic” in a true sense of being whole. As in – complementing our other faculties.

Slavs and Tatars, Exposition view, 2018. Photo: Margarita Ogoļceva, Latvian Centre for Contemporary Art, 2018

As this conversation inevitably – and unfortunately – is approaching its end, perhaps we could quickly return to unravelling the mystery behind your group. What was the initial idea behind the foundation of “Slavs and Tatars”? You said you started as a book club.

Yes, and we never actually planned to be artists. Our motivation was to translate things that are not translated before, to reprint things that have been out of print for a long time, to plug these gaps of knowledge... It was really about making knowledge available that was not readily available. That was the original idea. We didn't mean to become artists. It was actually the artworld that in fact invited our publications into its space, partly because they didn't fit in other categories... So, if you look at our books, you can see that they are analytical but they are not scholarly. They're not academical. They're journalistic, but they're not journalism... They're kind of sitting in an in-between space, again. Books that most publishers are not willing to accept. And this is important... We keep coming back to this... Because... Art has always been a platform for us, but it has never been a subject matter.

What do you mean?

I mean that our work rarely, if ever, touches upon art itself. The medium of art is a language, is a tool, but it's not... You know, there is a lot of art that is about art. Like perception studies and... We're not interested in that. We're not saying that's not valid – it's just not what we are interested in. We're interested in language politics, medieval advice literature, transliteration and topics like that. For us, art is a way – like religion, in some ways – to grapple with these ideas, but not in a purely analytical manner.

So one could say that because your interests are so unorthodox that they don't fit in any pre-defined areas of cultural activity, you have simply found the medium of art as the closest, best possible vehicle you can get?

Yes, exactly. A vehicle to educate ourselves and those who want to be with us. And we have a rather large appeal – I can tell it by the audience that comes to our lectures and by the response on the social media. And that's something I'm rather proud of.

Thank you very much.