Never listen to anybody

An interview with artist Julian Schnabel

16/11/2018

“Julian Schnabel is seen as one of the leading protagonists of painting in the last half of the 20th century and still influences painting today.” With these words, Julian Schnabel was introduced at ARoS Aarhus Kunstmuseum, where the biggest retrospective in the Nordic countries of his work is on show until March 3, 2019. It includes 40 large-format works of art, and the exhibition was organised in close collaboration with Schnabel himself and exposition architect Louise Kugelberg.

An insuppressible urge to speak in the superlative can often be observed when describing Schnabel. His breadth in painting, cinema and also his life seems to naturally lend itself to heightened emotions. He is one of those vivid phenomena that usually provoke extreme opinions – he may be absolutely revered or perhaps hatefully criticised. The documentary film A Private Portrait describes him as “larger than life”, an often-repeated quote that is, admittedly, quite precise, considering his charisma, painterly gestures, formats, density of emotions, multi-layered stories, thirst for experimentation and lust to create something new and unprecedented and live life to its fullest.

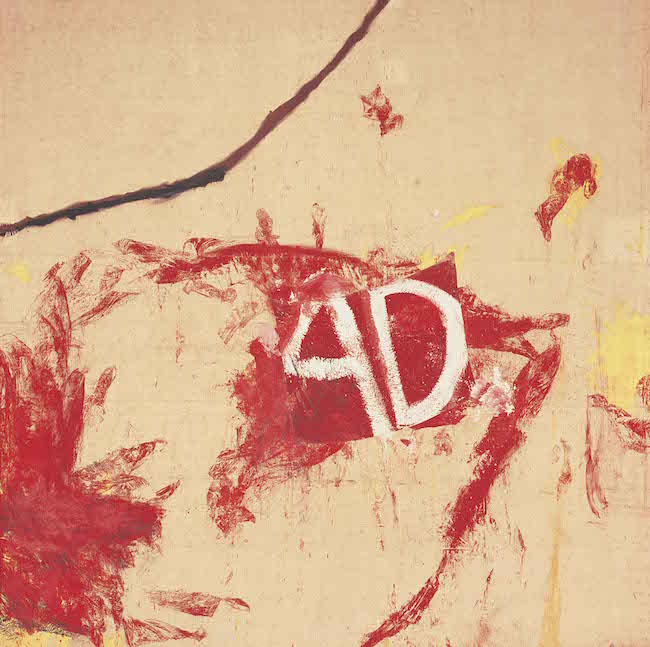

The exhibition at ARoS begins with three pieces (Anno Domini, Catherine Marie Ange and El Espontaneo [for Abelardo Martinez]) that Schnabel created in 1990 specially for the Maison Carrée, a Roman temple in Nîmes. At the time, they were the largest paintings he had ever made. When asked about his gigantic dimensions, he says, “Painting is still not that big, if you think about how big a mountain is, or an incredible landscape. Size is something that alters something’s meaning.”

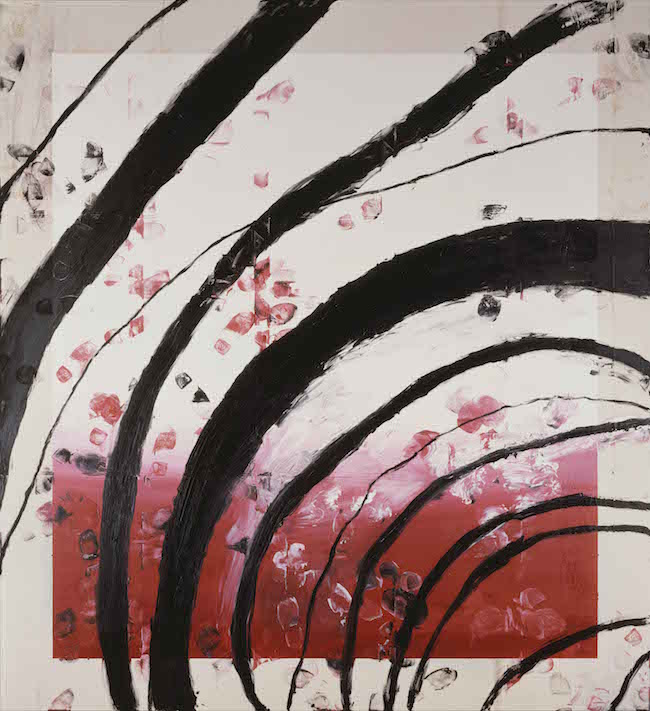

Julian Schnabel. Aktions Paintings. Photo: Anders Sune Berg

On the wall at the entrance to the Julian Schnabel: Aktion Paintings 1985–2017 exhibition we read Schnabel’s words from 1987: “Never listen to anybody when it comes to being responsible for your own paintings. It’s a mistake for young artists to want to please older ones. They’re going to make you take out of your paintings the very things that most characterise them as yours. You might think that someone is really smarter than you are, or wiser, or more experienced, and they may be. But you can’t listen to them because nobody knows better than you what you need to do. Most older artists are going to try to get you to conform to the standards that you are out to destroy anyway.”

Schnabel maintains that he’s always known he was a painter – as a child, when he was working as a chef at a New York restaurant, and also today, when he’s known as a film director. His newest film, the much-discussed At Eternity’s Gate, premiered on September 3 at the Venice Film Festival, with Willem Dafoe receiving the Coppa Volpi for best actor in his portrayal of Vincent van Gogh.

Our conversation took place in the vestibule of ARoS, next to the paintings mentioned in this text. Schnabel had just arrived from Paris that morning, where his exhibition Contemporary Interpretations (on view until January 13) had opened the previous evening at the Musée d’Orsay. He is the first contemporary artist to be featured at this famed citadel of art. The journalists in attendance wanted to know whether he is happy. “(..) if I wasn’t happy, I’d be really stupid,” he answers.

Julian Schnabel. Aktions Paintings. Photo: Anders Sune Berg

In a documentary about your life, the gallerist Mary Boone says that you turned the New York art scene upside down in the 1980s. Looking back with the perspective of time, what was your power back then? How did it happen?

I don’t know. I think I was very persistent. It’s very hard to answer a question like that... I think I probably wanted more than anything to make something that I hadn’t seen before. When you’re young, you want agreement for something, you want somebody to see what you see. And what do you see? Maybe you’re not seeing anything, and maybe you have nothing to offer them yet. If you look at the world now – I mean, people sending all of this stuff on the internet – they want to show something that they’re doing. You can’t even see what they’re doing, but they want to share it. There’s no reason to show anybody anything unless you have something to show them. But it takes a while to kind of figure that out.

At that time – it was 1978 – all I wanted to do was to invent something that I hadn’t seen before and find a way that I could make a painting that was personal to me.

And then, when I was in Barcelona, I saw benches created by Gaudí in Park Güell. I had this room with a closet that was sort of my size, and I got the idea – how about if I made the armature like that, covered with plates... I had seen a very terrible white mosaic in a mediocre restaurant I had gone to. White plates – because there were reflected lights and you could break these things and that could be on the surface. Instead of making something decorative, just make white plates! So I went home and made a painting called The Patients and the Doctors in 1978.

I remember I used to go Max’s Kansas City a lot. I went to that bar. I knew all these older artists who were siting there, and I said: “You should come over to my studio. I think I’ve got something that I want to show you.” And I remember these two guys coming over and looking... And I was very, very convinced that I had done something really great [laughs]. And one of them said: “That’s not a painting, that’s relief. A three-dimensional thing.”

I think the art is in communion with the working man. And they speak to that work, and the work speaks back to them. And in the solitude of that, something happens. I was working in a restaurant, and my father was very concerned. I had dyed blond hair, and I was working nights until three o’clock in the morning, and then I went home to paint. Then I had to go to sleep at about noon. And I got to sleep for five hours, and then I’d get up and go to work at six o’clock. My father was worried, because he thought I was a cook, but I knew I was a painter. It kind of charged me with this sense of identity.

I’ve been making this movie about Van Gogh now. You see this guy where people don’t really understand what he’s doing, but when he’s alone in nature, he’s extremely happy. Even though he gets lonely at a certain point, before that he pushes it to the far edge of life. There’s a scene where Willem Dafoe [Van Gogh – Ed.] is lying in this field and he pours dirt on his face. He takes the dirt and he sits up with this big smile on his face. Like he’s in the right place at the right time. I guess I got a lot out of making the paintings, and my connection with those things made everything else – obstacles or whatever – pretty irrelevant.

Julian Schnabel. Aktions Paintings. Photo: Anders Sune Berg

When talking about your career, you always say “I’m a painter”. But that’s kind of lost its relevance in today’s context of contemporary art processes. Painting is not a medium that’s widely represented at prestigious art shows, such as the Venice Biennale.

I think you’re right. Yeah... But it’s kind of not so interesting to me. A lot of the art that’s being made is also not so interesting to me. But Van Gogh is really good. Which painters do you like?

I guess I’d say Cy Twombly as the first one... He’s one of my favourites.

He was a good friend of mine. He liked my paintings a lot. And I liked his paintings. He gave me some things.

I knew him for almost 30 years. I was a kid when I met him. Twombly came to my studio in 1986 and saw two drawings on the floor. “Can I have those?” I said, “Yeah, you can have them.” And Cy said, “I’ll give you something for them some day.” And many years later he did – he gave me two drawings. And one day I was in Italy, and his brother-in-law – I think his name was Giorgio Franchetti – took me to his house. Cy didn’t know I was coming, but my two drawings that he had picked up from the floor were framed in 16th-century gold Florentina frames next to his bed.

That must have been a nice feeling.

Yeah. And he had this incredible Picasso drawing, this line drawing. I said: “What a great Picasso!” And he said to me, “I made that drawing.” So he made a Picasso. And so I thought, “OK, maybe I could do that, too.” I actually painted a couple of Picasso paintings that I have at home just because I wanted to have some lead paintings. My daughter Lola and her sister came home one day and saw them: “When did you get that?” I said, “Today.”

%20VIII_%202016_%20oil_%20plates%20and%20bondo%20on%20wood_%20182_9%20x%20152_4%20cm_%20private%20collection_%20Photo%20by%20Daniel%20Martinek%20Photography.jpg)

Julian Schnabel. Rose Painting (Near Van Gogh's Grave) VIII, 2016. Oil, plates and bondo on wood, 182,9 x 152,4 cm. Private collection. Photo by Daniel Martinek Photography

Picasso has always been particularly important for you.

The Blue Period and Rose Period show at the Musée d’Orsay now is really breathtaking. I mean, also the fact that he was 20 years old when he was doing these paintings. And people always think they’re blue because they’re supposed to be sad. But they’re blue because he wanted to make blue paintings, to limit his power and make a paint that he hadn’t seen before.

Your own work is now on show at the Musée d’Orsay in Paris. What does it feel like to exhibit your paintings next to Picasso and Van Gogh?

When Picasso was alive, he knew the director of the Louvre. They were friends, and he said, “Picasso, would you like to hang a painting next to somebody’s painting in the museum?” And Picasso said, “Yes, I’d like to hang it next to Zurbarán.” So, I mean, for me to hang these painting of Tina Chow next to Van Gogh’s self-portrait and look at the two paintings together, it was a very powerful feeling and a kind of respect. You don’t always get that kind of respect.

Julian Schnabel. Aktions Paintings. Photo: Anders Sune Berg

Are you happy?

Twenty people kept asking if I was happy, but if I wasn’t happy, I’d be really stupid.

You still do your art by yourself, by hand. What is so fascinating for you in that process? Do you believe that it’s a way to transfer your energy to the viewer, to the audience?

Sure. I mean also...I make something, and if it’s not right, I have to change it and find a way to make it better. I can’t order it, and then somebody sends it to me, and there it is and that’s it. That doesn’t work for me. I mean, it’s an interaction between... And the making of the thing, the process of doing it, is very much a part of the subject.

Julian Schnabel. Anno Domini, 1990. Oil on white tarpaulin, 670,6 x 670,6 cm. Courtesy the artist. Photo from Julian Schnabel Archive, 1990

Your retrospective here at ARoS begins with large-format pieces, of which three – Anno Domini, Catherine Marie Ange, and El Espontaneo (for Abelardo Martinez), made in 1990 – were located in the Maison Carrée in Nîmes for five years. At the time, they were the most monumental pieces you had made.

Yes, these paintings were made for the Maison Carrée, which is a Roman temple built by Caesar for his daughter. The way that these paintings were made... For example, for Anno Domini, I took a tablecloth, which is actually in the middle of the painting now, and I threw it at the canvas. So, all of these very carefully described images are made by just throwing a tablecloth at the painting. It looks like there’s a guy holding a piece of cloth there, and his arms are coming off there, it looks like there’s the bottom of somebody’s feet, but these things are not made with some preconception of a figure. It was just formed like that by throwing a tablecloth. And then, obviously, there are some parts that are more red than others, and I think really, in the most literal sense, seeing the bullfights in Nîmes affected these three pictures. Every day the bulls went into the ring, they died, so it was just “Anno Domini” – the year of.

Catherine Marie Ange was made the same way, by hitting the canvas with a tablecloth, and I thought this has something to do with angels. At one point I was thinking about calling it Los Angeles. Then, as I was walking out of the museum, there was a door that had been locked for seven years. I opened the door and found the identity card of a young girl that had been there that whole time. Her name was Catherine Marie Ange. So I figured that was about an angel, and I called the painting Catherine Marie Ange because of that identity card I found on the floor. But obviously, I’m looking at it as subjectively as anybody else. I didn’t think “Catherine Marie Ange” and then illustrate what I felt about this person, because I didn’t even know her. So, it just has something to do with my own subjectivity, or our subjectivity.

I hadn’t seen the paintings for a while. It’s kind of nice to hang them up and look at them and remember that time. I remember seeing Goodfellas by Martin Scorsese in Paris. There were a lot of people watching the movie. It was a very good movie. And then I took the train down to Nîmes. I had these three paintings in this temple [Maison Carrée – Ed.]. Nobody was in there, just me looking at the paintings and thinking, “Well this is...the ecstasy that I’ve chosen.” I want to just stand here and look at these things, and the audience is not there.

There’s a huge incongruity between art and life. And it’s funny as you get older, also. I don’t want to go to any openings, or I don’t want to meet any people. It’s... When you’re young, you think, oh, this is going to be a great thing, it could be exciting. But if a lot of people come, you can’t see the paintings. And if nobody comes, it’s a problem because the people don’t care. So you have to really just like to look at the paintings. I mean, it was my pleasure to see them in this space.

These paintings were painted vertically, not on the floor. On a ladder. I painted these paintings in Montauk, outside of a studio.

Is it important for you to paint in nature, or is it just for practical reasons?

No, I can see better. I like to be outside.

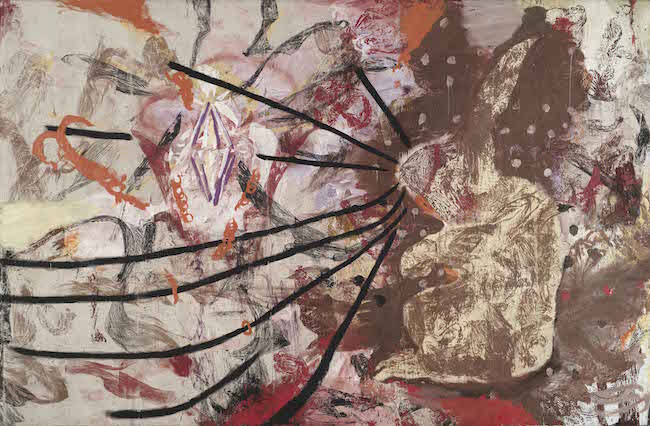

Julian Schnabel. A Carrot Is a Diamond to a Rabbit, 1990. Oil on tarpaulin, 472,4 x 721,4 cm. Courtesy the artist. Photo: Tom Powel Imaging

It seems that coincidences and random, chance events are important for you.

See, this painting [A Carrot Is a Diamond to a Rabbit – Ed.] is not as tall as the other ones. I started to work on this particular painting, and it drove me crazy, because it didn’t go with these three paintings. So I put it away for 22 years, and that’s the good thing about painting that’s different from movie making, for example. You can actually put your painting away for 22 years and nobody can say, “What happened to my money you put into the movie? You didn’t put your movie out for 22 years!” Well, that doesn’t happen if you’re a painter.

A Carrot Is a Diamond to a Rabbit has never been shown with these three paintings. And so it looked quite different, and I didn’t know if it was good or bad. But I guess after a while I felt like I could look at it.

It’s more busy…

It’s more busy, but it’s fine. And maybe that’s why I couldn’t look at it. But I quite like it now. And the dots that are there were made by taking a tennis ball, dipping it in paint, and then throwing the tennis ball at the painting. So, these painting have something to do with the notion of printing and drawing. I looked at it afterwards, and I thought this looks sort of like an Easter rabbit, like a chocolate rabbit, in a way. But it was not my intention to make a big rabbit – it was just a part of the process in forming the painting. There’s a way that paintings function where things fill up and then they get emptier, and that kind of rhythm, or transition, is something that I think about when I look at anything. I think that sometimes you want to make a requiem, and sometimes it’s a solo piano piece. There might be different impulses.

Julian Schnabel. Aktions Paintings. Photo: Anders Sune Berg

Returning to the monumental size of your paintings. This exhibition at ARoS distinctly represents the scope of the formats.

I don’t only make really big paintings. But I wanted to show some really big paintings in this space, because there was an opportunity to do that.

You know, some people like to surf in really big waves. I think that there’s an opportunity, or a sense of scale, that happens in the water or in nature. Painting is still not that big, if you think about how big a mountain is, or an incredible landscape. Size is something that alters something’s meaning. But I mean, obviously, when Caravaggio was making a painting like The Beheading of St. John the Baptist, people saw a big black painting. It looked like a screen. Maybe, when they saw it, they felt more like they were entering another story about life. So, it’s not really a new tendency. If you look at a Renaissance painting in Venice or whatever, there’s a kind of all-encompassing feeling to them that pulls you in. I mean, if you go to the Giotto chapel in Padua...

I’m not comparing my own painting to those things, but it’s a human impulse to sort of address something in between heaven and earth. It’s physical. We’re all about five and a half, six, six and a half feet tall. So, at a certain moment these things look taller than us, and so our perspective is relatively the same. We walk into that thing.

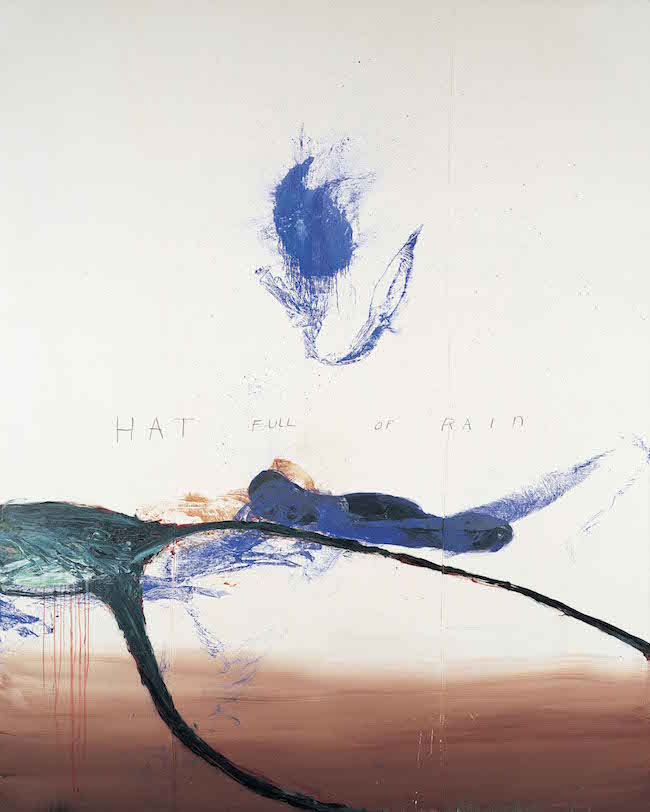

Julian Schnabel. Hat Full of Rain, 1996. Oil and marker on tarpaulin. Courtesy the artist. Photo from Julian Schnabel Archive, 1996

It seems that the substance itself is very important for you – the materiality of a surface, the physical feel of the paint. You’ve painted on velvet, on found materials that you’ve come across in various corners of the world. Their “former lives” and the imprints they’ve left behind have influenced your painting.

You look at it [War (Mexican Painting), 1986 – Ed.], and it’s not a new piece of white canvas. This was a piece of material that covered a truck in Mexico. The truck was broken down on the side of the road, so I asked the truck driver if I could buy his tarp. When I stretched it out in a plant nursery in the jungle, I saw an image in this canvas, a form that looked like an ostrich or a skeleton. Like some sort of monster. So, I drew what I had seen in the dirt. I had spent a lot of time in Mexico since I was a teenager, and I kind of felt like the violence of that country was coming up through my feet and I was just painting what I was feeling. I didn’t have any preconceptions about what I was going to paint. So, that was the first painting of this group.

After that, I went to a gas station and I talked to two other truck drivers so I could do two more. So, this is called War, and that one’s called Apathy. And that painting is called Consumption. And a really crazy thing happened. There was a guy named Albert Olsen, and he was not Jewish. Before Hitler came to power in the 1930s, he had a girlfriend named Hilda. She was Jewish. When Hitler came in, he left and went to London. But she stayed and married a Jewish man, and her whole family was sent to Auschwitz. And they were all killed, except for her and her sister. Albert Olsen felt like he should have called her and told her, “Get out of your house right now and just don’t look back,” but he didn’t do that. Anyway, after the war he went and found her in Czechoslovakia, and he got her sister and he brought them back. When I met them, they were living in Mexico. I was making this painting and I thought – I don’t know, does it really look like war? And I figured that if she were to see it, she would know if it looked like war or not. So, I picked them up in a jeep, and we drove over to look at this painting. She said yeah, but the face looks too human. So I painted the eye red and put some reddish brown in the eye, and then she thought it felt more like war.

Now, that’s the story, but you don’t need to know that to look at the painting. But it’s interesting how paintings can be a litmus test where people look at something and they start telling about themselves or they relate to it in some way that’s personal. I think that, probably, when I look at a painting – or the paintings that were available for me to see when I lived in New York in the early 1970s – what I could see didn’t really speak to me. I needed to make paintings that were more for me. It kind of didn’t necessarily fit in with what was going on there then, but it changed the way people were making paintings. And then...I guess the landscape of paintings looks quite different now.

Of course, if you ask Tarkovsky who his influences were, he’d say he didn’t have any. Of course, he did, but what he’s saying is, “I wanted to do it my way. I wanted to do it in a way that was personal to me.” And so, I think that’s probably what you see here. I was experimenting, and I still am, I guess.

Julian Schnabel. Big Girl Painting, 2013. Oil on canvas, 414 x 386,1 cm. Private collection. Photo: Tom Powel Imaging

It seems that it’s impossible to separate your painting and your films, these two forms of expression. They overlap in a way, they’re linked to each other. The Painting for Malik Joyeux and Bernardo Bertolucci (2006) exhibited here clearly brings to mind the surfer’s character in the film Basquiat, where he emerges from the wave above the skyscrapers... Or the newer plate paintings – Rose Paintings (Near Van Gogh’s Grave) – are obviously linked with your recent film, At Eternity’s Gate...

That’s a good way to put it, because I didn’t try to make...to separate. But obviously, when you apply yourself to a particular medium, and you have to work with that material, something comes up that’s different than using other material. But it’s funny, because I hadn’t thought about the image of surfing behind the buildings and Basquiat for a while. The same person who gave me that footage took the photograph when we were in Hawaii in 2004 that formed the basis for Painting for Malik Joyeux and Bernardo Bertolucci. I spent a lot of time looking at waves while surfing, and I still do it.

In that painting it’s a guy actually standing in the tube. There’s all of these different quantities of white, whether it’s the spray, or the reflection, or the bottom of the water, or the way the lip is coming over, and then... How do you compete with something as dramatic as that? I mean, when I was a kid I saw Seven Samurai by Kurosawa, and when these guys are riding their horses through the mud in the rain, it’s very, very powerful, particularly if you’re sitting in the front. And it’s very big and very violent. So how do you compete with that? Well, you have to make something that’s still, because you can’t compete with that.

Julian Schnabel. Last Attempt at Attracting Butterflies, 1994. Oil on canvas, 411,5 x 375,9 cm. Private collection. Photo: Ken Cohen Photography

In addition to absolute joy about life, death is also almost always present somewhere in your work. Are you not afraid of thinking about death so often?

But this is my way of dealing with death. I mean, this is a good question, because basically these paintings are all about that, and the movies I make are about that. I guess this is my way of dealing with death and mediating life through making things and addressing those questions. Because, when you see the movie about Van Gogh, it’s really not just about painting. It’s about anybody that ever wanted to make anything. It’s about just being alive, being in the present.