The museum is a forum

An interview with Sam Keller, the director of the Fondation Beyeler

29/11/2018

The Fondation Beyeler is not only the most-visited museum in Switzerland but also currently one of the most innovative and dynamic art spaces in Europe. It is a museum with not only its own character but also its own voice. It acts as a sort of flagman for the institutional environment – in addition to its basic mission of providing a secure and lasting haven for art and an ideal space for displaying art, it also serves as a platform for debates and discussions, thus forming a live dialogue between its visitors and current events and trends. At the same time, the museum deftly embodies a balance between art and entertainment that is sometimes difficult to find in this fragmented 21st century. Since its opening, the Fondation Beyeler has always stood apart with its superb exhibition programme and its ability to turn each show into an event.

The Fondation Beyeler was founded by legendary Swiss art dealer and collector Ernst Beyeler and his wife, Hildy, in 1997 (exactly 13 years before Ernst’s death). It was based on the core of the couple’s art collection, consisting of approximately 200 works of modern, post-Impressionist and post-war art: Picasso, Braque, Mondrian, Klee, Rothko, Giacometti, Francis Bacon... As Beyeler himself once said, the artwork in his collection gave him a better feeling than the money in his bank account.

The Fondation Beyeler found a home in the peaceful, picturesque park on the property of the Villa Berower. The museum building, designed by Italian architect Renzo Piano, exudes the essence of simplicity and an almost irrational poetic beauty. And it is this idyllic harmony between architecture, art and nature that has made the Fondation a destination for not only art lovers but also architecture aficionados.

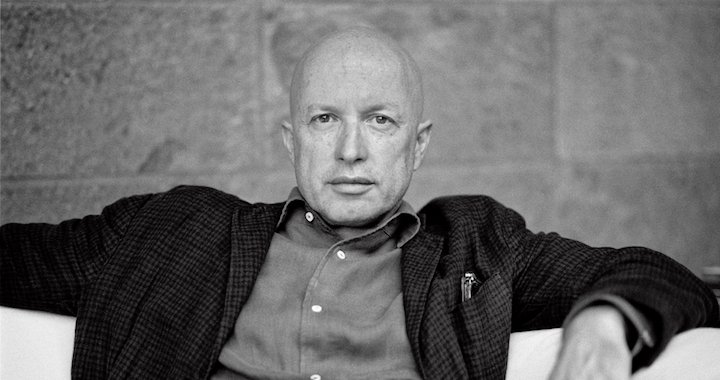

Sam Keller has been the director of the Fondation Beyeler for the past ten years; in fact, Beyeler himself selected Keller as his ideological successor. Before coming to the Fondation, Keller served as the director of Art Basel from 2000 to 2007, and he is considered one of the brightest visionaries on the current art scene. During his time, the Fondation Beyeler has grown to more than 300 works of art, including work by contemporary artists and long-term loans from other institutions and private collections. Last year the art world learned of the museum’s plans to build a new extension designed by well-known Basel-born Swiss architect Peter Zumthor. Symbolically, the project will be Zumthor’s first public architecture project in his native city.

Keller has a sharp mind, lots of charm, a showman’s talent and abundant charisma. During our conversation, which lasts about an hour, he smokes five cigarettes and the smile never vanishes from his face. We talk about what the museum as an institution can learn from nature and the laws that govern it, about the role of museums in the 21st century, and about why it was so important at precisely this moment for the Fondation Beyeler to organise an exhibition of work by controversial Polish-French artist Balthus (1908–2001). Among other things, the show includes Thérèse rêvant (Thérèse Dreaming, 1938), the painting that raised a scandal last year at the Metropolitan Museum of Art for supposedly romanticising child sexuality.

Balthus. La Rue, 1993. Oil on canvas, 195 x 240 cm. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Bequeathed by James Thrall Soby © Balthus Photo: © 2018. Digital image, The Museum of Modern Art, New York/Scala, Florence

After the moral panic that occurred at the Met, everyone was waiting with curiosity to see how the public and press would react to the Balthus exhibition here at the Fondation Beyeler. The show has now been on view for already more than a month, and, contrary to the Met’s experience, the reviews praise the Beyeler for doing this exhibition, even in the context of the #MeToo debate. Why was it so important for the Fondation to put on this show, and what kind of impact do you think it’s had, if any?

First of all, all of the exhibitions we do have their starting point in our collection and our history. In this case, we have one of Balthus’ masterpieces in our museum on long-term loan from a collection with which we’ve had a relationship for half a century, which is longer than our museum has existed. And we wanted to place this work within a context. It turns out that one of Balthus’ best friends was Giacometti, andwe have an important Giacometti collection. Other artists, including Picasso, collected Balthus’ works. But our one work by Balthus was a bit solitary, and we wanted to show it together with other works by him so that our visitors could better understand what led to the creation of these pictures and how our piece fits into his overall oeuvre.

We had already started to plan this exhibition before the #MeToo controversy came to light. Obviously, the situation at the Met led to us having a discussion about it at our museum. We asked ourselves what it means for us, and we decided that this is an opportunity – an opportunity for a museum to show why exhibitions as such are important, as well as what museums can provide that social media cannot. We also decided to extend both the educational programme and the ability for visitors to discuss and interact – our goal was to make the museum into a forum. Consequently, we’ve created a special programme that includes a podium discussion in which we open up the topic of freedom of art: what does it mean, does it have limits, should there be boundaries, etc.

We’ve also created guided tours for visitors that focus on that same topic. In fact, we have one of Balthus’ former models guiding the tour through the exhibition, and people can ask her directly what it was like to model for the artist. We also have a permanent staff member from our educational department at the museum who wears an ‘Ask me’ button and who is, to our surprise, very often approached by visitors. Most people ask questions about completely different topics [laughs], but people do appreciate it. Usually you have to book in advance to participate in the museum’s educational programme, but in this case you can get instant answers. It’s an opportunity for us to have one-on-one communication with our visitors, and that’s a good thing.

We also wanted visitors to have the opportunity to voice their opinions in this discussion, so we set up a wall on which we posted the statement by the woman who requested that the Metropolitan Museum take down the painting of young Thérèse Blanchard [Thérèse rêvant]. But on the same wall we’ve also posted the opinions of the artist’s friends and art scholars, and visitors can add their own opinions to the wall. We’ve also set up an online forum so that people can remotely participate as well. So, this show was an opportunity to show what a museum can do, and also an experiment of how a museum can act and react in this kind of situation. So far, the reaction has been extremely positive – we’ve not had any protests or anything like that.

So, nothing like what happened with the showing of Maurizio Cattelan’s Kaputt (2013), an installation featuring five taxidermied horses attached by their necks to a wall, which elicited protests by environmental activists.

Exactly. There have, of course, been negative reactions, but they have not been violent. I think one call to the police was made, in which someone complained that there’s pornography in the museum and that this shouldn’t be allowed, etc. We spoke to the police andin the end they turned down the case based on the fact that, in Switzerland, the law guarantees freedom of art and freedom of expression. So, even that turned out to be a good thing for us in terms of being a test for what could happen in such a situation.

So far, we’re very pleased with the media as well. The media like sensation, and we were a bit wary of what the tabloid press might do. But we’ve only had one critical article, in Der Spiegel, which had a bit of a sloppy argument but was, nevertheless, critical. Most articles, albeit with different arguments behind them, have focused on the art.

We also had a positive experience with some collectors who usually don’t lend out their works by Balthus simply because they love them so much. However, they decided that now was a good moment to lend them out for public viewing, which is why some of the works on view in our exhibition have not been seen by the public for decades.

Balthus. Les enfants blanchard, 1937. Oil on canvas, 125 x 130 cm. Musée national Picasso-Paris. Donation by the heirs of Picasso, 1973/1978 © Balthus. Photo: RMN-Grand Palais (Musée national Picasso-Paris) / Mathieu Rabeau

In a sense, the Balthus show is proof that museums currently have more freedom than, for example, social media. What do you think is the role of the museum in this rapidly changing world of ours?

I think that museums should not forget that, first of all, they are a safe place to keep art [laughs]! To conserve art for research, for the public, for education and for future generations. But a museum in the 21st century is also a museum for the people; it’s a place where people can actually exercise their civic rights. What good does it do for us to have freedom of expression and freedom of art if people are not allowed to post major works of art on Facebook just because there’s nudity in them? Consequently, some of these images can only be seen in a museum.

In addition, I think we have to learn that, in a democratic society, it’s very important to have a variety of opinions. We have to live with and understand the fact that people in our societies have different opinions; we must even support this fact, and we need to encourage people to have an exchange of opinions instead of having a dictatorship based on only one opinion. So, I think it’s also an experiment on how opinions come about in a democratic society: what is allowed, what is not allowed, what is good, what isn’t good and so on. Of course, a museum is a place for entertainment – a place to enjoy oneself – but it’s also a place for debate. Today, the culture of debate and discussion is something that seems to be increasingly fading away, but I believe that museums can actually help give people a voice and to have it heard.

Maybe we took these rights for granted for too long, especially in a liberal society like Switzerland. It used to be normal to have one’s opinion tolerated or heard, but now that this has been put into question, museums can step up and say yes, it still is possible. It is possible for people who have opposing opinions to go to the same place. They don’t have to shout at each other; they can even listen, and they can learn. Even we, as a museum, can learn from our visitors. We can learn from opinions that are different, and I think that society needs this. Museums shouldn’t be the only places doing this, but they should be the main players when it comes to art.

Museums cannot save the world by themselves; we have to understand that there are limits to what art can do and what museums can do. But we are great platforms, and we can do more than we have done up to now, especially in terms of the values that make up the basis of democratic society. Many of these values are essential for art and for museums, and here at the museum people can learn and practise using them. That will make museums even better.

Balthus. Therese, 1938. Oil on cardboard on wood, 100.3 x 81.3 cm. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Bequeathed by Mr. and Mrs. Allan D. Emil, in honor of William S. Lieberman, 1987 © Balthus. Photo: The Metropolitan Museum of Art/Art Resource/Scala, Florence

Everyone is obsessed with numbers today: the number of Facebook ‘likes’, record-setting prices at auctions, visitor numbers to museums/exhibitions and so on. Not long ago, museums were being touted as ‘the new churches’; now in some places they have to compete with shopping malls. How can art museums find the right balance between being entertaining (which is something many museums are focusing on) and being educational, that is, showing art for art’s sake? It does not look like an easy task.

No, it’s not. Balance is a key word that I always use with my staff. We like to refer to a quote from Albert Einstein: ‘Life is like riding a bicycle. To keep your balance, you must keep moving.’ I think the same applies to a museum – you cannot just stand by the one point of view you’ve always had and say that this is the way it is; you have to keep moving, you have to move along with society. However, you also have to reflect on these changes in a critical way, that is, evaluate what is good and what is not all that good. If you stand by one thing, that also means you’re not standing by something else.

We try to create a good balance between modern and contemporary art as well as a good balance among our visitors: well-educated art enthusiasts, scholars, the general public. We have programmes for the typical museum-goer generation as well as for very young people. We try to keep a balance between organising exhibitions, collection research and education. We try to keep a balance between exhibitions that attract a lot of people and those that we know are not going to attract a lot of people, yet we do them regardless, because we think that they’re important. So it’s a mix, but this mix never stays fixed. There’s always trial and error, and the museum reacts to developments in society.

What I think helps us in trying to foresee forthcoming developments in the art world is being close to the artists – we involve them in this dialogue. It also helps to live in the moment yet understand that a museum is a long-term project. If you only react to what’s happening right now, you’ll never be able to build a great museum.

A museum needs long-term plans. Some of the things we’re doing can be compared to planting seeds that will hopefully grow (at least some of them) so that the next generation will be able to harvest them. We’ve learned this from observing nature. As you can see, our museum is in a park, and when you have to deal with plants, you also learn a lot about museums. We want visitors to come every day and to have the museum and park looking good, but we also know that these trees are 200 years old and that at one point they will all die. Then we will need new trees, and if we don’t plant them now, the next generation will not have any great trees. There are other things you can learn from nature, for example, the fact that monocultures are not a good thing. Accordingly, we try to implement diversity.

We also know from nature that everything is connected by underground root systems.

Exactly. We also know from nature that, sooner or later, everything dies, although nothing disappears completely [laughs]. If you don’t plant, you can’t harvest.

The Fondation Beyeler. Designed by Renzo Piano. Photo: Mark Niedermann

When speaking about the recent Bacon/Giacometti exhibition here at the Fondation Beyeler, you said that you’re happy you can still afford to do such shows. How have current events in the art market affected the museum scene?

Well, they certainly have. Obviously, there’s both good and bad in everything. The art market is helpful because it discovers artists; the market also supports artists’ careers in the period before museums begin to acquire their work. However, these record auction prices that works by established artists are fetching are really a problem, because they greatly increase insurance and shipping costs. Also (even though our museum has perhaps not yet felt these repercussions), the higher the value of the work, the more hesitant the owner is to lend it out. In the end, it’s more work, and more work means higher costs.

One way in which we are affected is that it becomes increasingly harder for museums to do the kind of exhibitions that they want and need to do. Many museums can no longer afford to organise the kind of shows they would like to. As we all know, an aspect that concerns acquisitions is that, for a museum, time is an important element. A museum has to have some critical distance to what is happening now, and it would rather collect an artist over time, yet some works of art simply can’t be afforded anymore. Even with contemporary art, things can move very quickly. For example, there was an artist we showed here two years ago, and at the time, the works were priced under 100,000 euros. But over the past two years, the prices for this artist’s work have gone up by so much that we can no longer afford any work by this artist – an artist whom we have exhibited in the past. So that is, of course, a concern, and it makes things difficult.

Museums seem to have a major part in that whole ecosystem. They play an essential role in the validation of art, and they do research and many other things that cost money, while private buyers benefit enormously from the work being done by museums yet give back very little. In terms of balance, this aspect is very unbalanced. In essence, museums are being punished for hosting exhibitions of artists who then become so hyped that the prices for their work increase to the point that the museums can no longer continue to do their primary task.

The Beyeler Fondation’s founding collection focused on approximately 40 artists, and the collection is still expanding. How do you decide which new names to add to the collection?

Although the Fondation Beyeler is a public-private partnership, the founding collection was donated by the Beyelers, who also donated the building, which was very generous of them. The Beyeler collection spans roughly a century, from the late 19th century to the late 20th century, with most of it from the first half of the 20th century. At the time the museum was established, it did not have an acquisitions budget, and all of the works were donated by the Beyelers. Now the museum does have an acquisitions budget, and most of the works it now acquires are post 1950, the period from which the collection had the fewest works. And, of course, there is the contemporary art of the 21st century.

The works in the original Beyeler collection were, of course, contemporary at the time – that is, when artists like Picasso, Giacometti, Rothko and so on were active – whereas our contemporary artists are Gerhard Richter, Richard Serra, etc. Originally, the collection had no female artists, which at the time was very typical for collections built in the 20th century. So, this is also something that has been corrected. In addition, the original collection was very strong in terms of painting and sculptures, but now it has, of course, expanded to other mediums. For example, we have an important collection of work by Wolfgang Tillmans. We have work by Philippe Parreno, Pawel Althamer and other artists who work in different media. And we’ve added works of performance art by, for example, Tino Sehgal. We also acquire works from many of the artists with whom we do exhibitions.

What makes a great collection? Is a collection a personal memory or a collective one?

Well, the collections built by private collectors obviously differ from those of museums. Even the Beyelers, when they acted as private collectors, had different criteria for collecting, and they did not donate to the Fondation all of the works that they had collected privately, because they believed that the museum should preserve only the best for future generations. And not everything needs to be preserved; what is important in a particular period of time may not match what is important to a specific individual. Once the Beyelers had decided to donate their collection to the museum, they acquired more works specifically for the museum, and those were then kept separate from the works they had at home.

We at the museum, of course, now collect for the collective memory, but we are lucky to be in a situation in which we are not the only museum in the area – there are many museums here. Which is why we don’t think only about ourselves but also consider what is already here in Switzerland or Germany and especially in the city of Basel – what does the Kunstmuseum have, what is in the Hoffmanncollection and so on. We think about how we can build a great collective memory together, as a region.

In addition, we continue to focus on creating a history by trying to acquire important works of art which, together with what we already have in the collection, are more than the sum of their parts. For example, oftentimes a certain artist has a connection to another artist in the collection – sometimes in the same generation, sometimes across generations. We also sometimes show artists not as part of a certain grouping – say,German painters, French modernists or American abstract expressionists – but instead we try to show how these groups are not closed boxes but are in fact interconnected. We intertwine works from different generations or different geographical locations. Basing acquisitions not only on subject matter and medium, but also on other shared characteristics that are more abstract or anecdotal, makes for a rich and complex collection.

A good collection has some criteria that it follows, but not too strictly – it has to be like a living organism, like a truly interesting person. It has a personality, but not like that of, say, a character in a Hollywood action movie, who is simple and can be understood immediately. The deeper you go into a collection, the more connections you’ll discover. Good collections work for first-time visitors, but they also work for someone who comes back repeatedly, or for someone who does research and knows the collection really well – and this includes the people who work in the museum and our scholars. They continue to discover new things in the collection.

View of the permanent collection of the Fondation Beyeler. Monet room, 2013. Claude Monet, Le bassin aux nymphéas, around 1917–1920 and La cathédrale de Rouen: Le portail (Effet du matin), 1894. Fondation Beyeler, Riehen/Basel, Beyeler Collection Ellsworth Kelly, White Ring, 1963, private collection, © 2013, Ellsworth Kelly. Photo: Serge Hasenböhler

That fits with your comparison of a collection to a jungle – a place where everything is connected. I once had an interesting discussion with Thaddaeus Ropac in which he said that he believes that all good art should end up in a museum. Do you agree?

I think that there’s a natural way in which good art travels from the studio to a gallery or an art fair, a biennial, a kunsthalle or a temporary exhibition space, and from there to a private collection or perhaps even somewhere else. Great works of art usually end up in a museum or private collection that either regularly lends out the works or gives the public and scholars access to them. It’s in the interest of the artist, and of the art world, that this artwork is studied and seen. But it’s also in the interest of society at large, because it enriches our knowledge about ourselves, our time, our history. Again, that does not mean that this should be written into law, but we know that a museum is the safest place for a work of art in the long term. There are, however, some exceptional private collectors who have done a great job of keeping artwork over the centuries and giving others access to it.

But in general, I would agree that all good art should end up in a museum. Our life cycle is relatively short compared to that of a masterpiece. We live to a maximum of, say, 100 years, but if a work of art is truly great, there will be more than just two or three generations wanting to look at it. Moreover, perhaps the work will develop even more meaning in a period that comes after the artist’s death, or after the collector’s death. It’s like a family. If you have children, you will have noticed that when they grow up, they want to do some things differently than they were done when they were young. It’s natural that children will want to live not only according to their family’s heritage but will also want to add new things or change things. Likewise, for a museum, its history is always very important, and the historical artwork will always be treated very well, at least in most cases. I would say Thaddaeus is right, in general.

When Ernst Beyeler founded the Fondation Beyeler, the art world was still a very close circle. These days, art is everywhere, and many are trying to profit from it. Does it help art to maintain a level of quality and a core mission?

We all know that quantity has its advantages, but quantity also carries the risk of diluting quality. Why should it be any different with art? There’s not necessarily less quality in art today, even though there probably are more artists out there actually creating art, exhibiting it and living from it; there are also more magazines and more ways to display art. This increased quantity has its positive side, but if we go back to the metaphor of a landscape, it’s much easier to see something in a desert than in a jungle.

For my generation, we had to travel to see art. We had to save money to buy a book about art. Getting access to information was difficult, and to see a work of art was a really special thing. Now it has become much cheaper to fly, and because of the internet, everything is accessible. Everything grew so exponentially that we now have another problem, almost the reverse form of the original problem – we have too much information. However, I don’t think that one case is necessarily better than the other; we’re still only learning how to deal with this new landscape. I’m generally positive that we will learn; human beings are incredible learners and adapters to different landscapes. The differences between peoples who live in the desert, the jungle or in the polar regions are vast. It’s quite amazing how they’ve all adapted, so I’m positive that we will also adapt to this situation.

In general, more art is a positive thing for society, but it makes the work of a museum harder to do. Especially in terms of the element of time. If we think of the different dimensions at play, quantity is only one of the dimensions causing the problem. Fifty years ago, most museums didn’t even collect living artists; they had a whole lifetime in which to choose which art to preserve for the next generation. Nowadays, most museums are also showing art that’s fresh out of the studio. That creates new opportunities, but it also carries a new risk: we’re giving up this great thing called time.

So, museums just have to learn to do both: they have to become more multi-dimensional, but they still need to be very good about keeping the perspective of time, that is, keeping themselves at a critical distance from things, such as resisting trends and such things. But on the other hand, museums need to be extremely well informed and ‘in the middle of it all’ so that they can adapt very quickly to what is happening now, for example, in terms of their educational programmes or, sometimes, even going so far as making changes to an ongoing exhibition. It makes the work in a museum very challenging but also highly exciting. I wouldn’t want to live in another time.

You once said, during your early years at Art Basel, that you learned a lot about art from the art market. Do you think that the art market is still a good place to learn about art?

I think that art fairs have always had an advantage in terms of having a lot of concentrated information in one place at one time – information not only in the form of objects but also in the form of people who have information. Art is also a consensus. However, because there are so many art fairs and biennials now, they’ve lost some of this consensus-making process; it’s done differently now. Nevertheless, they’re still great places for meeting a great deal of people in a short time and seeing a lot of art.

But to really learn, you have to see a proper show, you have to study a proper book. I think a lot of people in the art market today think it’s enough to just follow people’s Instagram accounts and listen. We shouldn’t forget that there’s value in reading a book, in spending time in front of a work of art and in talking to an artist. It’s not that art fairs are a bad thing, but they’re not able to deliver the full picture. That would be impossible. They have tried – they have put more effort into education and into involving the artists, and they have done an incredible job with that. But it’s still not enough. Museums are needed more than ever, I believe.

Ernesto Neto. Gaiamothertree, 2018. Zurich Main Station. Fondation Beyeler. Photo: Mark Niedermann

The Fondation Beyeler is the most-visited museum in Switzerland. In many interviews, you’ve made it clear that you’re not interested in franchising the museum. In the meantime, the Fondation is a very active lender of artwork and collaborates with other museums all over the world. You’re also doing satellite projects, like the Ernesto Neto installation in Zurich’s central station last summer. Why are collaborations so important?

I think that life is essentially the act of collaborating [laughs]! I think this is how humans became the dominant species on this planet (which is a problem in itself) – through collaboration. And it’s the same for museums. We, as a museum, love diversity, and we think there should be diversity in museum models. It’s exciting to work with others who think the same way we do, but it’s also exciting to work with those who are very different.

For instance, we are now collaborating with the Museo del Prado and the Pushkin Museum, which is fantastic. It’s distinctly different than collaborating with museums like Tate Modern, Louisiana or Stedelijk, which are similar to us. The model of a franchise adds a lot of tension to the hardware, whereas we believe it should be more about the software – about the art itself. Collaborating means learning from each other and getting to know the best practices; it gets you outside of your own museum. It’s about sharing, which is a very good thing. It’s also a great way in which to make the museum a living organism. Of course, there are also practical reasons, such as cost reduction and so on, but apart from all this – even if there were no cost reductions – it’s still very important.

The same thing applies when it comes to public art. A museum is not just what happens within its walls; the museum encompasses everything that it produces within the world of culture. Sometimes a museum can consist of the relationships it has – it is also ‘a part of the museum’ when we visit an artist in his studio, or if an artist comes to visit us here. Art is at its best in a museum – at least, that applies to the vast majority of it – but some art truly is better in other locations, for example, outdoors or in a very urban environment, or perhaps in a completely different context. I learned that when I was doing a project – actually, a demonstration – with Santiago Sierra for Art Basel.

In the anti-immigration demonstrations that took place, especially in Germany, people held banners that said things like ‘Ausländer raus!’ (Foreigners out!), and they also wrote xenophobic things like that on walls and so on. Sierra did the inverse of that: he made banners that said ‘Inländer raus!’, meaning ‘Citizens out!’, and had a group of southern-looking people (i.e. Spanish, Portuguese, Italian, Turkish) go on a ‘demonstration’ while holding these banners. People were, of course, shocked about what the ‘demonstrators’ were saying. Sierra did the same thing on a beach in Majorca where Swiss and German tourists love to go, thereby putting a spotlight on the ongoing tension between the Spanish residents and the tourists. From that, I learned how very good it can sometimes be to change the context of a work and how that can give it new meaning.

We also try to do a public art project every year, which means that the art goes to the people instead of the people having to go to the art. For example, by holding the Ernesto Neto project at the Zurich railway station, which is one of the most-visited places in the whole country, we had maximum diversity in terms of the people who saw it. Even if over 70% of the Swiss population goes to a museum at least once a year, that still means that a quarter of the population does not. And that quarter can be reached there, in the train station. Not to mention the fact that there are people who are not so fortunate as we are to live in a country with so much good art, and the train station is the number-one entry point for tourists coming into the country from all over the world. It was a very good experience.

And Ernesto Neto is a great artist as well.

Not all artists can do a project that would work in this context.

You spent many years together with Ernst Beyeler. What did you learn from him, and what of that is still relevant today?

He wasn’t the kind of teacher who tells you to come with him, to do this like that and so on – not at all. He taught by example, and he was more of a mentor. He helped you find your own way: do what you want to do, I will support you. When he first asked me to be the museum’s director, I told him that I had never been a museum director – I had only worked at the lowest level of a museum when I was a student, so I didn’t know much about it. He said that I would have much to learn, but that shouldn’t be a problem. I asked him what he would like me to do, to which he replied that I have to do it my own way. He never told me to do an exhibition in a certain way... That’s one thing I learned from him – that good teaching is not telling people what to do but saying, ‘I know you already have a lot of the basics down, so go and make your own experience.’ A good teacher trusts that the student will make well-informed decisions and, if needed, will help the student and give them the means to do what they want to.

He gave me freedom and opportunities, but also challenges. So, yes, it was a big challenge for me [laughs]! I never had the typical student-teacher relationship with him. I learned other things from him, like from his comments. For example, sometimes we would sit here and watch the visitors coming out of the museum, and he would say, ‘The best thing about this job is that we get the satisfaction of seeing how much people appreciate our work.’ This was encouraging, especially during times when you’re very tired, and it helped us to remember why we do what we do. Look at the people coming out: they’re experiencing a reaction. They might have just spent the best hour of their day, the best day of their week or even, as I’ve actually heard sometimes said, one of the best moments of their life. We are very privileged. It’s great to be able to work if you have motivation like that.

Another thing I did is accompany him when looking at art; that’s still very relevant to me. He would be silent when looking at art. He didn’t look at everything; he could also walk by things. But when he saw something that sparked a reaction in him, he could stay and look and look – much longer than an average person would have done. He would spend five, ten, even fifteen minutes looking at one painting. I would think to myself, ‘What is he doing?’ And he did it silently. Learning how to look is very difficult to teach to another person. Not everything reveals itself instantly.

We would also talk about, for example, why he did not sell this Picasso or this big, wonderful Water Lilies triptych by Monet. He answered: ‘I exhibited it two times. I wanted to sell it, but nobody wanted to buy it. At the time, it was too radical for people – they would say, “Perhaps it’s unfinished...” I spent time with it, and then I grew to understand that it was a great work. By the time people wanted to buy it, I no longer wanted to sell it.’

I also remember a conversation with him about a specific work from the collection which he had bought and put up for sale in his gallery. It eventually sold, and then later, as a collector, he bought it back at a much higher price. I asked him if this didn’t frustrate him, to now have to pay 100 times the amount he had sold it for. He said that if you know it’s a great work, and if you have the money, go for it. He often paid record prices for artwork. Now people wouldn’t see that as being expensive, but it was a record price at that time. If you see that it has great quality, if it’s a potential masterpiece, and if you have the ability, buy it. You’ll regret the things you have not done, not the things you have done.

One of the main qualities of his collection, he said, was that he had collected ‘tried and tested’ works. He would say: ‘I don’t care about being the first one, I want to be the last one. It is not my honour to say that I discovered this artist before everyone else did.’ It was important to him, especially in terms of the museum collection, to not be the first one but rather the last one to own the work of art. So, it’s alright to take some time until things have been ‘tested’ and then pay a much higher price. Those are some of the many things that he said and which have stayed with me. Sometimes they help me make decisions.

But he was a very humble person as well: he would ride a bicycle when his clients were already travelling by private jet. Can we even speak about such a quality as humbleness in terms of today’s art market? Or has it gone, along with Beyeler and ‘the gentleman’s handshake’?

First of all, I think humbleness is something that comes from within a person and which cannot be learned. It forms from the experiences a person has gone through, and it’s also influenced by one’s cultural surroundings. Of course, it helps that Basel is an old city, very understated, and actually favours people like that. Unlike, for example, a young city where people come in, make big promises, and then disappear. Yes, he was humble, which came from his upbringing but also from his experience. Maybe this was something that helped him keep his feet on the ground...to not lose his bearings whilst in the midst of rich and famous people. But he was also a man of enormous ambition and vision, so it was not enough to be humble [laughs]. He had one foot on the ground, but he was also like a tree – with deep roots and with branches that reached up to the sky. In fact, the branches couldn’t go high enough for him. I think that both are necessary – both roots and branches.

What happened with the gallery that he had here in Basel?

We discussed what should happen to his gallery, and in the end he decided – and I was very supportive of his decision – that he is the gallery and that the gallery is he. It was founded by him, and it would end with him. He stated in his will that the gallery should close one year after his death. Sometimes we discussed whether the gallery should continue, but we decided that it would be better for the Fondation Beyeler to have just the museum. Although it would be nice to have a gallery as a source of income [laughs]!

But if you want to be a serious museum, you have to be only a museum; you cannot be involved in the art market as well. I, myself, have never sold a work of art. I have never wanted to do that. I think Beyeler made the right decision. It was a great time – in his prime, he had one of the greatest galleries in the world, and no one could do it better than him, but times are different now. Good things can also have a good end; they don’t need to go on forever until they meet a bad end. I think it was a happy ending that went according to plan. The gallery’s stock was sold to benefit the museum, as was everything from his private estate. Which is one reason we can continue to collect and create exhibitions.

In the 1980s, Beyeler switched his interest from Europe to the American art scene. Why did that happen?

I think Beyeler was one of the best-informed gallerists of the time. He had already begun travelling to America in the 1950s. Also, Basel was amongst the first cities in Europe to show American art, which I think also had a big impact. Beyeler was friends with Mark Rothko, Barnett Newman, Roy Lichtensteinand many other artists, so I think it was also his personal experience. But most of all, there was a kind of canon. After the Second World War, things shifted and he was a witness to how things developed and how the New York school became important and so on. And, because he always wanted to collect the best art of his time, he had to go to America. As a successful art dealer and collector here in Basel, he had access to that.

But he was not exclusive. He also collected Giacometti, Bacon... He continued to collect European artists as well. What he added was American post-war art – abstract expressionism and pop art. And once Robert Rauschenbergwon the prize at the Venice Biennale, it was clear that this was not happening just in America – it had also become a dominant art movement here. Beyeler was witness to that. One of his best friends, who was also one of his most important intellectual conversation partners, was William Rubin, the chief creator of the painting and sculpture department at MoMA. The two of them were very close and often exchanged ideas. The MoMA canon was one that Beyeler championed very much; he influenced it, but it also influenced him.

What’s interesting is that, after a while, Beyeler left America and went back to Europe, to Baselitz, Kiefer and Richter. I think the last work he bought was by Neo Rauch; German painting had again become his focus. Sometimes I would ask him why he hadn’t bought this one or that one, and he would say, ‘Well, I missed that train; I’ll get on the next one.’ He didn’t try to cover everything. There were certain things that were important to him and that were important to art history, and that was enough.

With this, I can also come back to your question of why this is such a great collection. Because it was a collection that was made with deliberate, informed decisions. No museum can cover the whole world – that’s an illusion. It’s much better to go in the opposite direction. And Beyeler could do that because there are other great museums in Basel, in Zurich, in Germany, in Paris that cover lots of things, so you don’t have to do it all. No one can do it all.

The extension project of the Fondation Beyeler by Atelier Peter Zumthor. House for Art and Pavilion (right-hand side), view from the Berower Park. Courtesy Atelier Peter Zumthor & Partner

You used to be quite critical regarding museum expansions, but now you’re doing it yourself. At what stage is the Fondation Beyeler extension project now? Do you already have a date for construction to start?

No. Tomorrow I’m actually going to Peter Zumthor’s studio, which is in the mountains. It all takes time. The planning takes time, the permits take time, raising the money takes time. But time is a good thing for a museum; it may be one of the most important materials that we work with.

One thing that I didn’t mention about Beyeler was that he would always say: ‘Quality first. Quality is the most important thing. When you orient yourself towards quality, all other things will follow.’ That was always a guideline for him, and that’s also one of the things I try to continue with. For example, when you’re constructing a building, you have three main parameters: quality, time and money. And you have to prioritise. Yes, the budget is, of course, a limit.But the time in which we live and work is also limited. Perhaps, if you’re a commercial investor, the money is the most important thing. Or, if you have to build quickly, like in an emergency, then you’re limited by time. But for us, a museum, quality is what limits us. Quality comes first, and, seeing as the budget is also limited, the easiest thing to be flexible on is time. Once the museum is built, who cares when it opens? Once it’s built, it will be there for generations. Future generations will not judge it on how quickly it was built or how much it cost – they will judge it based on its quality.