“Art is a bodily activity of movement in space”

An interview with artist William Kentridge

23/04/2019

One of Europe’s oldest art forums, the Holland Festival, was founded in 1947 and will witness its 72nd edition this year. The festival has always had a simple and laconic air about it as it announces its programme of the best opera, dance and music performed by the world’s best artists. This summer, the Holland Festival (May 29 – June 23) is titled “The World on Stage” and will introduce a new model of collaboration involving two associate artists. Both of these artists, William Kentridge (South Africa) and Faustin Linyekula (Congo), live and work in Sub-Saharan Africa. In addition, both of them work on a global scale and have a very unique, personal artistic voice.

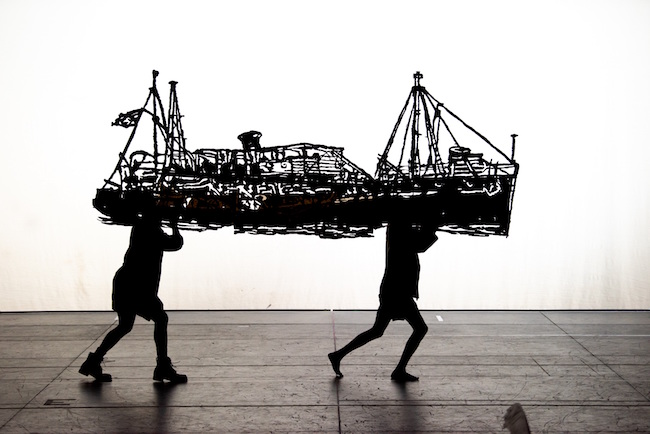

The Head & The Load © Stella Oliver

The Holland Festival will open with Kentridge’s new music theatre production The Head & The Load, an epic homage to the hundreds of thousands of African porters and carriers who served in the British, French and German forces during the First World War. The music for the production (which combines music, dance, film, mechanised sculpture and shadow play) was written by Philip Miller, one of South Africa’s leading composers.

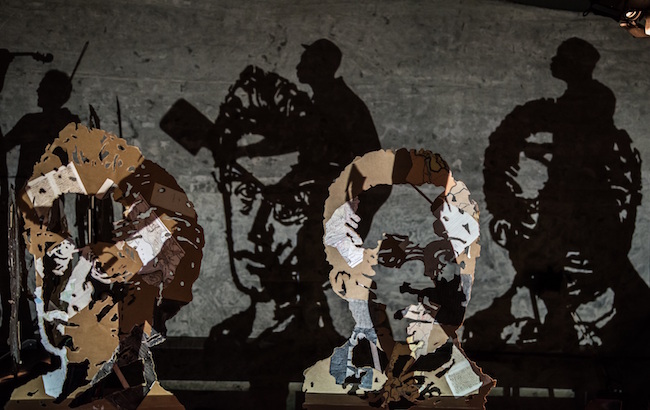

Paper Music @ Berliner Festspiele - Foreign Affairs © Christopher Hewitt

In addition to the opening show, the festival will also feature Kentridge’s cross-genre performances Paper Music and Ursonate, and the Eye Film Museum will host the retrospective project-exhibition William Kentridge: Ten Drawings for Projection (June 3 – September 1). The latter event will include the series of ten short films about South Africa’s turbulent history that Kentridge made between 1989 and 2011. They marked his breakthrough onto the international art scene, and in 2015 he donated the films to the Eye Film Museum. The exhibition will also include the film installation O Sentimental Machine (2015), which revolves around a speech recorded by Russian revolutionary Leon Trotsky while he was living in exile in Turkey.

Kentridge was born in 1955 in Johannesburg, South Africa. He studied politics and African studies at university and then fine art at the Johannesburg Art Foundation. He later also studied mime and theatre in Paris. Today he is known as a multimedia artist who merges film, sound, music, sculpture, collage, theatre, animation...and seemingly simple charcoal drawing into a single artistic whole with admirable virtuosity and lightness. It embodies both the unworldly and the topical. Like the palimpsest technology he uses so often, Kentridge’s works are like a procession in which the global intertwines with the private, history with the present day, technologies with the artist’s presence in the studio. His art illuminates the past in order to be conscious of the present and to survive in the future. It contains no estrangement; instead, it is saturated with a feeling of presence. It addresses the viewer poetically but also very directly. It challenges the viewer both intellectually and emotionally. Although Kentridge is considered a political artist, his artwork embodies the authenticity of a handmade drawing. He is a drawer, both in the literal and figurative sense. His work has been shown at the Venice Biennale, documenta, Tate Modern in London and the Museum of Modern Art in New York; as an opera and theatre director he has worked with the Metropolitan Opera in New York and the Royal Opera House in London. Kentridge is without doubt one of the most prolific artists of our day.

This interview took place virtually. Kentridge was in his studio in Johannesburg, and I was in Riga. When he finished answering my last question, the time was 10:30 in the evening in Johannesburg (11:30 pm in Riga) and the rain had just begun to fall outside his window...

The Head & The Load © Stella Oliver

The title of your work The Head & The Load is taken from the Ghanaian proverb “the head and the load are the troubles of the neck”. What are the biggest troubles for artists in the times we’re living in right now?

You are certainly asking me hard questions! Let’s come back to that first one in due course.

In your artwork, you choose to speak about very serious subjects (like the aftermath of apartheid and colonialism, totalitarianism, war and injustice) in a lyrical way. Why did you choose this kind of language?

One doesn’t choose one’s language; one discovers what one’s language is a long way into the work.

I think that what was clear to me from the first few years of working in my studio was that there’s a mixture of a personal connection to the images I was making – whether they were of me and my wife, or my family, or childhood memories – and things beyond that, broadly. Images of what was happening in South Africa or broader questions that interested me. It was a bit like a diary in which everything was allowed in, from the personal to the political to the social. And it was about gradually discovering the uncertainties one has about understanding one’s immediate life or merging one’s uncertainties of understanding the broader social life. And if the net result is lyricism rather than stridency, that’s a bonus, but it’s not something that you would attempt to do. It’s what you discover at the end.

The Head & The Load © Stella Oliver

Your artwork very often contains the idea of history as collage. Is there something we can name as objective history, or is all of history a patchwork made up of subjective fragments?

I don’t think that the fragments necessarily have to be subjective. It’s a question of understanding that a single narrative that proclaims an understanding made through the procession of events always comes from a particular viewpoint, and that there are always other viewpoints. And that to understand history is to understand the range of different ways of understanding the world, and to also understand the sources of one’s own ignorance. It’s understanding what is ignorance that has been constructed by other people. It’s understanding facts that are hidden from us, or facts that are there but we don’t see them because our heads are so full of other thoughts. And that there are things that we see but can’t give them the importance they deserve because of other patterns of thinking that we have. So I think that history as a collage is an important way of understanding the world. What it does is it makes us sceptical of the certainties that come with a single narrative of history.

Procession is one of the elements that’s very common in your work. As we know, procession is also part of religious ceremonies and public celebrations. Why is the ritual of procession important for you as an artistic tool?

One of the things about procession is that it enables one to draw this wide range of people, as opposed to a single static image in which you have your eight people that can fit across a canvas – more if you make them very small. If they’re coming towards you, you’re still stuck with those same eight people coming towards you. But if it’s a lateral procession, you can itemise all the people in the world that you’re interested in or who come towards you. So the sideways procession, which comes all the way from Plato’s Cave, is of people carrying objects that cast shadows on the wall. Up till the drawings that I do. There’s something about the multiplicity of people in the world that is shown in these lateral, sideways-moving processions...

The Head & The Load © Stella Oliver

Your art is a multi-faceted, multi-dimensional practice that combines drawing, theatre, music, sculpture, performance, shadow play, etc. Does this, in a way, provide an answer for the future of art? That is, in these fast-changing times, can the authenticity and the true essence of an artist’s expression only be found in relation? In this relation that leaves an imprint that’s impossible to copy or replicate?

I don’t have any predictions of this being the future of art. I’m very aware of the debt I have to the last hundred years, to what Dada achieved from 1916 onwards. The way in which they, through their repudiation of art as a form, enabled art as a practice to be so much wider. So if you’re an artist, you can work with music, with theatre, with performance, with poetry, with dance and still preserve your heart as a visual artist.

If you’re a poet or a writer, this would be much more difficult, and this has to do with the risks and the brazenness of the Dadaistsand the Surrealists that followed them 100 years ago. And it certainly means that in the art world there is an openness regarding what one can do, which is a blessing. I’m not sure that it will last forever, but there’s no sign of it abating at the moment. All forms – whether they’re film, writing, poetry or music – are available to the artist as part of the vocabulary through which the world can be explored or remade or reimagined.

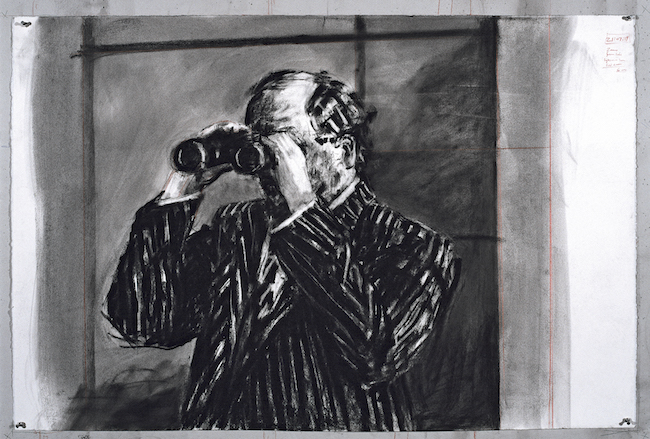

William Kentridge. 10 Drawings for Projection. Drawing for the film Tide Table (2003).

You once said that “drawing is a non-verbal thinking process”. But is making art a conscious process? Or is it a special zone – not the real world we live in, but something that comes out, because there is some mystery about it as well?

These are such hard questions you ask me! Trying to put a finger on what it is that one does. I think one starts with an impulse, a connection to the world somewhere – either to the world outside, to the social world, or to the world of the history of image making that one responds to. And then, through the process of making, one discovers not what the answer is but, I suppose, what the question is. I think of it much more simply in the sense that one invites the world into one’s studio. In the form of images, memories, dreams, photostats on the wall, postcards, books, all the things that a studio is filled with – physical things for the most part.

And then one fragments and rearranges the world, and one sends a rearranged image of that world back out into the world in the form of a film or a drawing or a novel. And that is the work of an artist. This taking of elements from the world and reconstructing them. In a way, showing at the most basic level that all our understanding of the world is this construction of a possible coherence from a mess of different fragments, which could result in an incoherence but which we have a deep psychic need to render into a coherence.

You’ve said that you have a need to be making marks on paper. Why? And why do you have a need to make them with charcoal?

I think the impulse to be an artist is not that you have something specific to say, but instead you have the need to do something to make a physical manifestation of yourself. It always has to do with a lack or an inadequacy in the world – that to be yourself in the world is not enough. You need to leave some trace of yourself that is outside of yourself. So you can see yourself in the way that other people look at something you have made; so this independent object to be looked at can stand in for yourself at a certain point. And this is the need I mention for making a mark, but it could just as well be a need for making a sound, for making a gesture. One would have to speak to a psychoanalyst to discover what is the deep origin of this need in some people and the absolute lack of this need in other people and to understand the blessing of not having this need.

Why is it important for you to create your art by yourself, by hand?

Art is a bodily activity of movement in space, in the studio. It’s the use of muscle and energy, of finding the edge of what your body is, even if it’s just the edge of your knuckles when you’re doing a very fine detail drawing. That’s a central part of art. It’s not a cerebral activity in which you sit in a chair and think, at least not for me. It’s only when I’m up off the chair and moving, or in contact with the material, that I feel like there’s a life or a thought that I trust. The thoughts I have when I’m just sitting in a chair are non-existent – my mind goes into neutral gear. I wouldn’t trust those thoughts as far as I could spit.

And so the hand for me is an essential part of art. There are many projects I do in which many other hands are involved, such as in making a sculpture or weaving tapestries. But it never helps for me to have someone else doing the drawing. It would feel very strange to delegate that activity to someone else. But there are a lot of activities at the edge of the drawing in which many other people are vital.

The Head & The Load © Stella Oliver

You’ve always been an artist of black and white. Does this mean that colour is insignificant for you?

No, there’s definitely colour in my work. But most of it is found colour on maps or on colour charts. Some people are tone deaf, while others can hold a tune. I’m one of those who is tone deaf, and I would also say that I’m colour deaf. It’s not that I can’t see when colours are wrong or awkward in how they fit together, or wonderful when they are correct, but in the same way that knowing when something is out of tune doesn’t help me to sing in tune, the fact that I can see when colours are wrong doesn’t help me to mix colours that feel appropriate. When I mix colours, I always end up in the same, very narrow range. So my only hope is by finding and assembling colours in different ways.

But there’s something about monochrome work, about black-and-white work, that connects to printing, to black-and-white photography, to the history of image-making techniques like engraving and etching and woodblock printing, that brings the work closer to the world of printing and writing and reading and further away from the world of the simulacrum of the textures of the world that you get in, say, the tradition of oil painting in northern Europe from the Renaissance onwards.

Your work is full of different kinds of references, and you have a huge collection of images and things to which you refer to throughout your working process. What do you collect and what do you consider worth collecting?

I’m not a collector by nature. Over the forty years or so that I’ve been working as an artist, I’ve ended up with several images in my house that are mainly images of prints by artists that I’ve loved and images that were very important to me as a student, as a young artist. Images by Goya, some images by Dürer or Rembrandt. But for a lifetime of looking at art, there are very few objects and images that sit on the walls of my house.

But there’s a kind of a slowly increasing vocabulary of images in the objects and images that I draw. Each time I think I’m drawing something new, I discover that I’ve already drawn it 15 years ago. I once made a list of things I’ve drawn and a second list of things I have not drawn, and I found that even though I instructed myself to only draw things from the second list – from the list of things I’d never drawn before, such as a hippopotamus rather than a rhinoceros, or certain breeds of dogs, or kinds of food – I found that I would rather draw 403 rhinoceroses than draw my first hippopotamus. So, it’s not like one has free choice of what images one is going to draw; certain images sit in one’s muscles and inside one’s head. Others are foreign to that.

Very often you work in a large-scale format. Why? Do you agree that monumentalism impacts viewers more directly?

Monumentalism is interesting, particularly if you’re working with projection, because you could do a small drawing and it becomes enormous when projected onto a large wall. So, I work a lot with a kind of provisional monumentalism. I sometimes do small drawings that turn into large-scale tapestries, and more recently I’ve been working with sculptures that have expanded from something you could hold in your hand to something you can walk underneath.

And I’m still uncertain about what that shift in scale means, whether it’s just a kind of bombastic manspreading or whether there’s something fundamentally different in the weight of an object of that size that confronts you. I’ve made some large sculptures that are being cast, and when they’re finished, I’ll be able to assess whether they’re folly or whether there’s an interest in them.

William Kentridge’s monumental frieze Triumphs and Laments on the banks of Tiber River in Rome, 2016. Photo: Una Meistere

William Kentridge’s monumental frieze Triumphs and Laments on the banks of Tiber River in Rome, 2016. Photo: Una Meistere

In 2016 you created Triumphs and Laments, a 500-metre-long impermanent frieze on the embankments of the Tiber River in Rome. It was left to decay there. Do you agree that an ephemeral imprint can sometimes be stronger and leave a more lasting impression on viewers than something permanent, also in art?

Triumphs and Laments was not ephemeral by design; it was ephemeral out of necessity. It works with nature, with the changing colour of the wall, with the bacteria either dying or flourishing on the travertine walls. I thought the images would last a good seven years, but in fact they will probably last four years. It’s sad to see some of the images disappearing, but they’re at the halfway stage now, and they have a magical presence of seeming to emanate out of the rocks themselves, like a fortuitous stain on the blocks of stone.

And when they’re gone, they will remain a presence for those who remember them as a memory, or for those who see them in a book, or for those who hear about them. But then the embankment walls will become a blank canvas again for other people to draw on. So there’s an appropriateness with the way our memories disappear and histories disappear; but also, this work doesn’t proclaim itself as the one final definitive history of the city of Rome and of Italy. Instead, it’s one viewpoint from which many others can either be critical or devise their own histories.

Do you believe that art can make the world a better place? Does it have the power to change anything in this advanced capitalist society that we’re living in now, which is balanced around extremes?

The way I think about the power of art is by thinking about it in my own case, from my personal art experience, from the ways that I’ve been shaped by historical events around me, by familial impulses and by the particular books I’ve read, the films I’ve seen, the music I’ve heard at different points in my life, and I realise that there’s a huge amount of consolidation of who one is.

Through these cultural works, through these confirmations of impulses that one has, suddenly there’s the excitement of a new way of seeing the world, of a sense of community with other people in the world who’ve read the same book that you’ve read, and you find a connection with each other through that book. And I think that this way in which individuals construct themselves – even in advanced capitalist societies – is fundamental to who we are.

I don’t have a sense of a work of art immediately changing society, although, having said that, many of the things that appear on social media appear to have this power. And, instead of being simply a 200-character text, they could just as well be a good or bad piece of art. The world changes, and it’s changed through the people in it, and they’re changed by many different things, of which art, literature and music are just several fundamental and essential elements.

What is the biggest responsibility of an artist today, if any?

The biggest responsibility... I always take comfort in Gabriel García Márquez saying that the revolutionary duty of a writer is to write well, or, for an artist it would be to work conscientiously in his studio. And everything else will flow out from that.

Do you think future generations will be able to understand how we lived and what we thought by looking at your art and today’s art in general?

If you looked at my art, you might get a particular viewpoint on the history of South Africa over the past forty years, but it would be one particular take on it. Now, I would hate to have the responsibility of representing South African history or South African art overall. But it happens. We know that our sense of different cities is formed by, for example, detective novels set in those cities, which we then imagine. Like our sense of different places is structured enormously by the operas we’ve seen about them, the novels we’ve read about them, the stories we’ve heard about them, the films we’ve seen.

We’re always trying to construct a coherence from whatever fragments we get, and even if the fragments are imperfect, or even wrong, that doesn’t stop us from imagining what that world could be. And that seems to be one of the fundamental characteristics of what it is to be human. It’s this insatiable need to make sense of the world as it presents itself to us.

William Kentridge © Jochem Sanders