Contemporary Drawing: The Underdog Who Ends Up Winning

A conversation with German conceptual artist Nadine Fecht about the oldest art medium still keeping up with the times.

27/06/2019

German-born artist Nadine Fecht (1976) creates works in various art media – works on paper, installation, audio and video works, and even the development of conceptual smartphone applications. Nevertheless, Fecht's whole creative practice is based on the idea of drawing being an independent work of art; she maintains that a drawing is not just a sketch on paper but rather a practice that continues to expand. She discovered early on that the simplicity and democratic nature of drawing as a medium contains unlimited allure and potential for expression, as well as a sense of poetry, intricacy, and truth that manifests not only linearly on the surface of the paper but also in interaction with other art media.

In a way, Nadine Fecht could be called an anti-hedonistic modern-day flâneur – a city wanderer who endeavors to see what goes unnoticed because of having become so self-evident or accepted as something that is simply not seen anymore. Fecht describes her own approach to the creation of art in analogy to Truman Capote’s writings, which were based on real events; in her case – based on real-life phenomena. By focusing her attention on them, Fecht asks a provocative question – what must happen for an individual to fall outside the scope of influence of something? At the confluence of her tangents of interests, abstract concepts and issues of a sociopolitical nature meet up with an individual’s relationship with oneself and the norms that have been imposed on by society.

_Copyright%20NadineFecht_1.jpg)

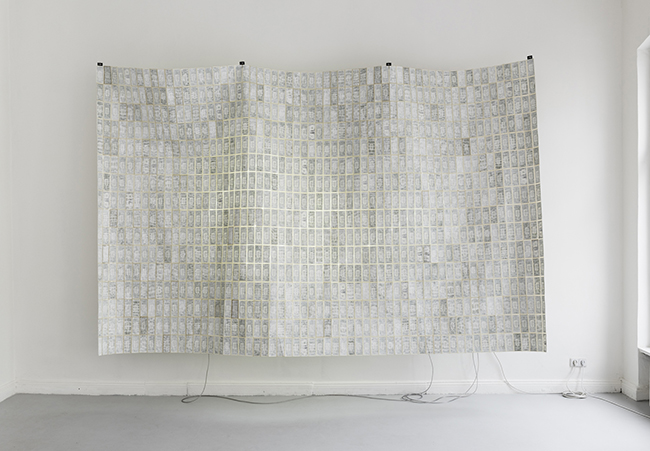

Priviledged. 2018. Copyright Nadine Fecht

During our conversation in Fecht’s studio – located in an industrial area in the Schoeneweide district on the outskirts of Berlin – she freely admits that her chosen artistic medium, in conjunction with personally set conditions, may not be the easiest way to turn an idea into a substantive form, but she sees it as a challenging venture that she has set for herself. Her studio space is whitewashed and filled with white paper rolls. In the very center of the room stands the largest drafting table I had ever seen. The crisp of bright sunlight flows through the windows and reflects in a tiny “pocket mirror” placed on the wall high above the sink. After the conversation, I was thinking for a long time about the small mirror that could barely fulfill its function. I remembered the words that Nadine Fecht said during our conversation: “As an artist, I do not aspire to talk about myself as an individual who sees the world. I am a mediator or medium that highlights a phenomenon in the world on a structural level.”

Nadine Fecht is a recipient of the Will Grohmann Prize, an endowment award given by Berlin’s prestigious Akademie der Künste. Her large-scale works on paper have been exhibited at Kunstmuseum Basel, Kupferstichkabinett, SMB Berlin, Kunstverein Harburger Bahnhof, the Museum for Concrete Art, and Akademie der Künste Berlin. This summer, from July 19 until October 13 her works will be on display during an (extensive) survey exhibition at Kunsthalle Mannheim. Her works can also be found in several private and public art collections in both Germany and Switzerland.

For the past four years, Fecht has been actively teaching conceptual drawing classes at Braunschweig University of Art and Mozarteum University Salzburg. Drawing is Fecht's key to getting into the deepest entrenched social constructs, and currently, as an interim professor for drawing, she inspires art students to find their own authentic base from which to work.

%20-%20exhibition%20view%20Kupferstichkabinett%20Berlin_Copyright%20NadineFecht.jpg)

Jedes Kollektiv Braucht Eine Richtung, 2012. Exhibition view, Kupferstichkabinett Berlin. Copyright Nadine Fecht

At first, I knew you as a new-media artist for whom I contributed a voice-act for the affirmation app© you were developing in 2017. It was later on, I learned that Nadine Fecht was also a brilliant draftsman. Tell me a bit about your background.

In the beginning, I simply couldn’t think of anything else than becoming or being an artist. Not exactly a painter or graphic artist, nor did I want to be classified as a representative of minimalism or conceptual art; I transferred from my initial studies in Karlsruhe to Berlin.

I purposely looked for a place to live in what was the former East Berlin, and by becoming a part of reunified German society, I slowly began to get to know what had previously been beyond my field of view but which I was consciously reaching towards.

I studied lens-based art at Berlin University of the Arts (UdK) under the Canadian video artist and professor Stan Douglas, and I received my diploma after graduating from the class led by the installation artist Lothar Baumgarten. Neither of these professors had anything to do with drawing, and their teaching methods were starkly different from each other as well, yet Douglas and Baumgarten have had the greatest influence on my creative work. Lothar Baumgarten was a student of Joseph Beuys, and much like Beuys was also interested in what could not be said, described or captured by words – in a sense, transcendental and magical things.

Beuys’s ‘alchemy’ has fascinated me since my schooldays – the virtuosity with which he could integrate a myriad of ‘alien’ materials into art, highlighting their characteristics or, conversely, hiding them, thereby creating a new message. This approach to material alchemy also manifests in my works. Namely, my art medium is any medium that can, relative to the subject matter, best resembles the idea which I want the viewer to experience. In terms of the medium, I consider a pencil as being on equal terms with a graphical user interface on a contemporary communication device.

I'm open to any medium, including the digital. I have a digital studio at home, whereas here, in my actual studio space, not even a laptop is brought in.

_copyright%20Nadine%20Fecht.jpg)

Affirmation app© 2017. Sound recording. Copyright Nadine Fecht

What makes up the foundation of your creativity?

Observing. Not observations made during en plein air exercises, but observations of societal phenomena, trends, attitudes and, sometimes, that sort of vague tension in the air that can only be sensed. I wouldn’t call myself a research-based artist, yet I often set specific parameters for myself so that I experience something different or from another angle. Beginning with things that are in my power to influence, such as the environment in which I live. When one is in flux categories that usually hold for stability are shifting and one falls back on essential basics which gives me a kind of independence in view.

How would you define drawing in the 21st century?

The audio-video installation close reading (2013), which was commissioned by the Akademie der Künste for a thematic exhibition titled Culture: City, includes linear elements. The film consists of a black image, an audio recording, and simultaneous subtitles in four languages. The sound material consists of four speakers whose native languages are English, Spanish, German and French, respectively. They were asked to explain in their own words, in their mother tongue, loanwords that have entered their language from foreign tongues, e.g. burnout, bourgeoisie, guerrilla, angst, etc. For example, in German, angst means fear, but in American English, the same word is used to denote a type of intangible subconscious fear one could call paranoia. Language is alive – terminology ages out and new words emerge. During the exchange of information between cultures – or let’s say communities – foreign words are adopted but their meaning may no longer be the same as in the originating language. In close reading, one only reads four subtitle lines which are the transcript and its translations of the word definitions given by the speakers in the four languages, with the specific loanword highlighted in red. I see this digital highlighting of certain words as being connectable to the concept of drawing.

_Copyright%20NadineFecht.jpg)

Close reading. 2013. Copyright NadineFecht

How would you describe the attitude of art institutions towards works on paper, especially contemporary drawing?

Along with the new millennium, drawing as a medium has experienced another renaissance – it has once again moved from artists’ sketchbooks and dimly lit ateliers to the attention of the museum audience. The number of exhibitions that feature works on paper is growing – not only at the Museums of Prints and Drawings (e.g Kupferstichkabinett Berlin) but also at art spaces that are not primarily focused on drawings and works on paper. Over the past ten or so years, it seems that art institutions increasingly want to take on the function of patron and consequently emphasize the role of drawing in art history and its growing popularity in contemporary art. Museums such as the Albertina in Vienna and Hamburger Kunsthalle have dedicated thematic (media-specific) exhibitions to works on paper, both by exhibiting works from their collections and by selecting contextual themes. After undergoing renovations, the newly opened Herzog Anton Ulrich-Museum in Braunschweig even hosted a symbolically broad exhibition dedicated to drawing through the centuries – from Dürer, Munch and Warhol to the most recent works falling under the ‘category’ of drawing.

After its successful debut in 2018, this will be the second year for the works-on-paper art fair Paper Position, an independent satellite event to the headlining Art Basel. It bears noting that works on paper, drawings, and collages require the viewer’s full attention as well as much closer viewing distances.

Drawings should not be separated but should be featured next to the showstoppers at fairs; they must be allowed to surprise the audience with either their loud tranquility or their quiet unrest. It is this outsider status that drawing has that really irritates me. In recent years though, international fairs featuring works on paper have become more visible.

Subjectivity as a material to trade. Photo: Marcus Schneider.

Subjectivity as a material to trade. Photo: Marcus Schneider

Do your works have points where the theme, material, and form of the work come together?

I develop groups and series of minimalist conceptual works. A conceptual similarity can be seen in my works – their core is made up of intangible processes and observations whose visualization does not require complicated means of expression. By way of minimalist gestures, I direct the viewer's perception in the desired direction of where the internalized takes on a new focus and acquires a more specific form. When I realized “field recording” a solo exhibition in 2011 in Berlin’s gallery for contemporary drawing, a typical white cube showroom with a grey floor, I also colored the entire floor white to dim down all visual noises. In order to also include large fields of linseed oil that would serve as visual pauses I homogenized the space so that, in its uniform silence, a conspicuous layer of dust would form on the white surface. I use digital media just as conceptually. I'm an ordinary user of Instagram and Facebook, but from day one I’ve been analyzing my and other users' behavior and interactions. These platforms are currently popular, but they may soon lose their relevance. Someday these observations will take on physical form, but first, they will be stored in my inner archive of intangible phenomena.

Before I start each work, I do technical tests and I approximately know the result that I want. After the experimental phase, I set different developmental parameters, namely, is it important in this case that there is a physical presence on paper, or can it be external? These prerequisites also play a role in the development of the work because I am convinced that the viewer will also perceive this, even if not quite to the level of pointing their finger and saying ‘This is the mark of Fecht!’ Only when the preconditions for the particular work are clear do I start the performative part – which sometimes brings unexpected surprises. In creating noise, sized 3,5 by 4,5 meters, I intended to create a sense of absence and therefore avoided my own physical presence on paper. In the end, I used huge scrolls of paper like in the Middle Ages – rolling them open at one end and rolling them shut at the other.

_Copyright%20NadineFecht_2.jpg)

Exhausted Self. Hysteria. 2006. Copyright Nadine Fecht

You are bound by concrete, but at the same time – abstract, concepts. Is there space for unconscious impulses and personal narratives in your works?

The unconscious is the foundation of everything...the way we react to the world. As an artist, I do not aspire to talk about myself as an individual who sees the world. I am a mediator or medium that highlights a phenomenon in the world on a structural level. In my beginnings, I couldn't yet fully function as an artist. I lacked the material to create. Not in terms of directly commenting on current affairs or issues that trouble society, but in the sense that it is my responsibility as an artist to be a part of what is going on and to be close to society at large. I see myself as a utopian who tries to make a meaningful contribution to society by always looking for new potential.

Let’s talk about work hysteria. If I were to be so bold as to characterize this series in one sentence, I would say it is ‘a performance that took place without any eyewitnesses’.

That is a very precise description! Drawing in itself is a performative act in which, without any witnesses, each controlled hand movement, as well as every mistake, is recorded on paper. The processuality captured in the work is a very crucial aspect. I believe that everyone can approximate how much time it takes to draw a line or how long it takes to write a sentence. hysteria (2016) consists of five separate drawings 205x140 cm in size. Taking into account these parameters, the viewer more or less understands how time-consuming it was to produce this particular piece.

The initial impulse for hysteria is based on reading Foucault’s The History of Sexuality. A passage about female hysteria stroke a nerve...and then disappointment. It's like a meme, a collective memory passed down from generation to generation. It took me quite a long time to achieve in my works the directness seen in hysteria. And also great daring. If you write the anti-affirmation ‘I am not hysterical’ hundreds of times, like an obsessed maniac, of course, the public's reaction will be ‘You are too!’ Although I am not at the center of the work, to some extent, either willingly or unwillingly, I am within its context.

‘Hysteria’ is no longer a proper term used in modern medicine, yet in feminist theory, as well as in society, the false and offensive belief that hysteria is a kind of female manifesto has taken root.

_mimikry%20wall%20drawing%20(2017)_Copyright%20NadineFecht.jpg)

Hysteria, 2016. Mimikry wall drawing, 2017. Copyright NadineFecht

You also have a work entitled Melancholia currently on display at Kunsthalle Mannheim in which ‘I am feeling blue’ has been written in red ink.

The phrase ‘I am feeling blue’ describes a melancholic mood of sadness. I am intrigued by German philosopher Walter Benjamin’s notion of melancholy who wrote in his work titled Origin of the German Tragic Drama that creative potential hides within melancholy and that enlightenment can be found. In a melancholic state, one is able to look at things while being distanced, almost detached, from their original function or meaning; for example, once this table has lost its function and opportunity to just be a table – in combination with other objects and in another context, it can generate new potential and new knowledge. The first prerequisite for starting work on Melancholia was to realize it in a large-scale, stretched landscape format so that when standing in front of it, the viewer would be looking at a vast panorama of reflection obviously expanding the viewer’s bodily dimensions. In this case, melancholy is not the emotional state of myself but of all society, which must daily face the dictation of super-capitalism. Today, in the arts as in other areas, the individual’s burden of responsibility and duty is unbearable.

%20detail_copyright%20Nadine%20Fecht.jpg)

Melancholia. 2015-2016. Detail. Copyright Nadine Fecht

In my opinion, the chosen format and theme of the work requires more than just sitting down and slowly continuing to work on a drawing. Was the creation of this work also an internal process? To what extent does daily life affect your handwriting, your grip of the pen, and your productivity each time you start up working on the same piece?

I set specific rules for myself in creating these works, and it was impossible to deviate from them. It is an emancipated act of self-discipline – a profane exercise in the grueling practice of handwriting. Every day I would arrive at the studio, refill my pen with red ink, and write ‘I am feeling blue’ until the pen’s ink reservoir was empty. These breaks in the color of the ink, as well as the uncompleted sentences, are visible in the work. By counting these breaks in the ink, you could calculate how many days it took to create this work.

Of course, the daily handwriting would change, the speed of writing would change – one day it was slower, another day it would be more energetic. The human factor that organically appears on the paper is extremely fascinating to me and in fact what I am looking for. I actually count on this human factor of imperfection to appear within the creation process – I cannot influence it nor can it be scheduled – otherwise it would be staged. If a defect cannot be transformed into a benefit, then at least accept it and include it as a part of the work. I am a human being – my creations cannot be impeccable. Because the works are minimalist, every decision or coincidence inevitably becomes part of the work, which I then pass on to the viewer to interpret.

_sweatshop(2015)_copyright%20Nadine%20Fecht.jpg)

Melancholia. 2015-2016. Sweatshop 2015. Copyright Nadine Fecht

Psychologists say that a new habit develops within 21 days. Repetition of a new activity contributes to the development of automatism. How do you feel after working on a series of drawings for weeks, even months, and then one day, ‘the final t is crossed and the final i is dotted’? Does it feel like something is missing when you return to your daily routine?

That’s a good question. From the art market point of view, it would be great if I continued to do one specific thing that would clearly show my individual signature and ‘artist’s brand’, but that’s not me. It is in my nature to be constantly experimenting with materials and changing the formats in which I work and their form in terms of content. With every new series of drawings, I introduce the viewer to something new, or to an aspect of perception I gained working on previous ones. A work of art has to give me back the added value of knowledge. When the message has been expressed, I simply move on because there is so much that has not yet been expressed. The essential topics in art might pretty much stay the same but our current handling and the required statement change essentially. I can only rely on my own sensor of relevance. My own comfort zone is definitely not a fertile place for developing art – if I do not give myself the opportunity to get to know the spherical world from another aspect, I can no longer create anything with meaning.

Do you have any special rituals for triggering the creation process?

I turn on the radio or start specific political podcasts. As soon as I hear the quiet drone of the radio and the headlines of the day being read, I’m in the mood for working. In addition, I’m focused while listening to the radio. I can't work en plein air. Although we are now outside the center of Berlin, I need to be in a more or less urbanized environment in order to work. The city's relentless sound and energy that is in the air during working hours – for me, it is crucial on a personal level.

Studio View. 2019. Copyright Nadine Fecht

You currently are an interim professor of the basic curriculum for experimental drawing at the Braunschweig University of Art. Have you, in any sense, assumed a style of teaching similar to that of your former professors Stan Douglas or Lothar Baumgarten?

Perhaps other students of theirs have very different memories than I do. The key role of the professor is to help young artists to find their authentic language and express themselves. I would say one must have a number of other abilities in addition to success in their personal career. I myself truly believe that everyone has the potential to express themselves creatively, visually or otherwise. And it is my responsibility to sense this, see it, and empathetically make students find their strengths themselves. Often times students are, for some reason, guided to act against themselves and their abilities.

During my studies, Berlin University of the Arts (UdK) did not have a specific professor-led drawing class, but I experimented a lot in various workshops, even experimenting with claymation. In my studies, I changed professors several times, which I’d advise students to do until you find someone who fits with you and moves you forward. For a while, I was in one class with mostly painting students. Every time the professor looked at my drawings, he would urge me to transfer the ‘sketches’ and move on to canvas. Hey! These are not ‘sketches’! I don't want to transfer anything onto the canvas! Another professor would say ‘do this and that’, but when I switched to Stan Douglas’s video art class, I finally experienced media-critical discourse (which included drawing as well).

_photo%20Marcus%20Schneider.jpg)

Surplus. 2013 - 2018. Detail. Photo: Marcus Schneider

How do you open up students to experimental thinking? To see the potential of drawing in video work, the potential of drawing in sculpture, the potential of drawing in shadows and in the airplane condensation trails between the clouds? If I were a student getting a classical education, I would rather reluctantly accept that classical teaching is one thing, but contemporary drawing is something completely different. Do you feel any resistance from students?

Not exactly resistance, but there is doubt. It's convenient to think in categories. They make you feel safe. You can always place your trust in categories. Especially, for the time being, I feel a tendency to rely on conservative foundations in order to feel safe. I observe my students – each one of them. I urge them to do their work with the highest precision, but even more carefully – to observe. Each one is a specialist with in-depth knowledge of something – an expert in at least one thing. In seminars, I try to help students discover their existing potential. And again I think of Beuys, who said that everyone is an artist. Everyone has creative abilities. The chosen medium need not necessarily be the drawing. However, my teaching is based on drawing – both as an autonomous work of art and the role it can play in other modern-day art disciplines: lens-based and sound art, sculpture, etc. Drawing, in my opinion, is a hypotenuse – the shortest and most accurate way for an idea to take form.

_photo%20Marcus%20Schneider.jpg)

Sweatshop 2015. Photo: Marcus Schneider

.JPG)