Why haven’t animals revolted against humans yet?

A conversation with German – Iraqi artist and animal activist Lin May Saeed

08/01/20

Lin May Saeed is a Berlin-based German-Iraqi artist whose art focuses on the relationship between animals and humans and the undeniable ambiguity in that relationship over the course of time. That contradictory relationship has included joy and love as well as cruelty, insensitivity and a groundless feeling of superiority on the part of humans towards animals. At the same time, however, humans are quite conscious of the fact that they need animals much more than animals need them.

Saeed advocates for animal rights. However, unlike overt activism, which often screams its message out loud, Saeed uses a sometimes even seemingly naïve language of art in order to elicit empathy. She is very aware of the fact that the well-being of animals is not the most popular of topics, and that applies to the contemporary art scene as well. On the contrary, her focus on animals is likely one of the factors that has long prevented her from being taken seriously. Reviews of her work often mention that she’s ahead of the times. But perhaps now, within the discourse of climate change, she’s finally in step with the times.

Saeed’s main medium is sculpture, but she also works with paper, drawing and video. She graduated from the prestigious Kunstakademie Düsseldorf, where she studied under Tony Cragg. She is known for her use of non-traditional and often humble materials (such as Styrofoam), which in a way heightens the essence of her message – Saeed’s work is about understanding and listening. Her work is about what it means to be not understood and how to find balance in a world where harmony is still a utopian dream. And this perspective might partly be based in her own personal experience and origins.

Saeed’s father is from Iraq, but Saeed herself was born in Germany and has visited Iraq only once. “I was very young when we went there in the mid-1970s, which is called the golden era of Iraq. My parents travelled to Baghdad to visit my father’s family, and we spent some time there. I’ve been told a story about how one night they went to a club and everybody was dancing. There was a person standing alone, leaning against a pillar, and my aunt said: ‘That’s Saddam Hussein. He will be the next president.’ Later, when Saddam became president, it was no longer possible for us to go to Iraq. There were two wars and a political-economic blockade. My father never went there again. He could have been forced to serve in the army. He already had German citizenship, but the danger was still too great.”

“My father died very young,” Saeed continues. “I had the telephone number of only one relative in Iraq. That was before the internet, and I tried to keep in contact. Many people fled the country as refugees in 2003, along with the start of the Iraq War and George Bush’s invasion. My relatives left Baghdad in 2006, and, like many refugees, they headed to Jordan, which is where I met them.”

Saeed shares her studio with two rabbits, who now and then during our conversation remind us of their presence with some friendly grunts, clucks and scratching.

Lin May Saeed

Lin May Saeed

Why does empathy with animals remain so rare in art?

There are certainly several reasons. One of them could be that, for a long time, visual art was not only a field dominated by male artists, but also, and perhaps more crucial, it was predominantly male content that was negotiated in art. Take, for instance, the hunting still lifes from the 17th and 18th centuries, and what you see there are hares hanging from their feet or dead pheasants and other birds draped on a table. That kind of art legitimises the killing of animals.

In the past, advocacy for animals in all their forms was often practised by women. Now we see the attribution of gender roles critically and find ourselves in a time of post-gender thinking and non-binarity. But if we look back in history, whether we think of suffragettes like Lizzy Lind af Hageby, who co-founded the modern animal rights movement at the beginning of the 20th century, or the founders of later animal rights organisations at the end of the century, most of them were women. It may then come as no surprise that for a long time there was little overlap between the male-dominated arts and female activism for animals. What I want to do with my work is to bring animal liberation and the right of animals to live to the fore through art iconography.

How did your link with the animal world start? What first got you involved?

I was a very young kid and I saw an information stand in a pedestrian zone showing photographs of animal testing. When I saw those photos, almost a world broke down for me, and I thought that things cannot go on like this. But I was a child, seven or eight years old. When I started studying at the Kunstakademie Düsseldorf in the 1990s, I noticed that people were again starting to think that wearing fur was normal. Düsseldorf is first a city of fashion, and only then a city of art. I started distributing leaflets encouraging people to not wear fur, and I did that on Königsallee, which is the most prestigious shopping street in Düsseldorf. I met other activists, who explained that many companies still do animal testing. Like many people, I was convinced that animal testing had ended long ago, that it was a story of the 1980s.

I realised that there are so many things that happen to animals and that you can see them separately, but you can also find a common denominator. There’s a name for that, which is “speciesism” – it’s a form of oppression against beings who are not human. It’s similar to the terms racism and sexism. Like, an ideology in which you think that you can do things to animals because they’re lower beings than we are. When I realised how interconnected all of this is, I wanted to focus on this in my work. But it took a long time, because I didn’t know how to do it. I finished my studies in 2001, and it took me five years to get an idea of how I could start doing work about the human-animal relationship.

The Liberation of Animals from the Cages XVI, 2014. Installation with cut out / screed cardboard, transparent paper, wood, lit up from behind with strip lights

There’s a kind of innocence in your pictorial language. Why did you choose this style of expression to speak about serious issues?

Animals are my main topic, and animals are innocent. I never consciously chose innocence as a style. But maybe I decided against something else. What would be the opposite of innocence – pictures that contain an attribution of guilt? Many people feel guilty about animals anyway, and feelings of guilt make them angry. But I don’t want this kind of mood when people look at my art.

In the past, I’ve so often experienced people getting aggressive about the topic, both in a private context and when talking to strangers in public. For example, we could get spit on during a demonstration against fur in front of the KaDeWe [a luxury department store – Ed.] in Berlin. With my artistic work I don’t want to pretend that I know much better, for example, about how to create an authoritative narrative. Having experienced aggression against myself and others, my attempt was to de-escalate the animal theme.

Do you feel that you understand animals?

Which ones?

The ones in your sculptures.

Animals – I mean real ones – are silent, they have a secret. Maybe that’s not the right word, but it’s very important for me to emphasise that I do not produce my works. My works take a long time to develop and to evolve, and the process is more like gardening. I don’t mean that I water the sculptures, but it feels a bit like that; I have to clean up, I have to do all the same things over and over again, and I look at the works for a long time.

I see my sculptures as subjects instead of objects. I was thinking about this for a long time before I decided to do sculpture and before I started my studies. There’s such a big difference between an object and a subject. For instance, recently a sculpture of mine found a new home, and the people told me that it spoke to them. I was so happy to hear that, because this is how I live with the sculptures. I try to make something that’s more intelligent than I am. That’s what I find the most exciting. That it’s independent from me.

The Liberation of Animals from the Cages VI / Asylum, 2009. Styrofoam, acrylic paint, aluminium foil, wood

Sculpture is like a living being.

Exactly. We don’t really know how intelligent animals are. Maybe they’re so much more intelligent than we think and are just keeping an oath of silence.

Then why are animals so patient and haven’t revolted against humans yet?

Honestly, I don’t know. But I love the idea that they will revolt. I tried to show exactly that in several works of mine, like Krieg from 2006. Probably they will revolt together with robots, and then they will send us home.

And home is where?

That’s a good question!

You’ve worked with Styrofoam as a material, and you once said that you’re drawn to it in large part because of its ugliness. Why did you make this choice?

There are many reasons. The first work I did with Styrofoam was in 2001, for my exam. At first, I hated it, because it makes a terrible sound, it sticks to your textiles, you have it everywhere, and it can be annoying. But in the field of sculpture, where you need physical strength to do big sculptures, Styrofoam also gave me a sense of empowerment. I could do everything on my own. Other sculptors need assistance, they need tools to lift their works of art, etc. But I never had those problems. I couldn’t afford assistance or to send my drafts to a production company. And that was also not the way I wanted to work. I prefer a more intimate work situation. All of this spoke in favour of Styrofoam. After a while, I stopped feeling aggressive towards it. Sometimes a thing that you at first don’t like at all can later become important. But of course, just the fact that Styrofoam exists shows that something is wrong. In a perfect world, there would be no Styrofoam. Styrofoam will survive us; it’s nondegradable.

I like to take something like Styrofoam or raw steel and try to make something more beautiful out of it. Because I think that a different human-animal relationship could lead to a more paradise-like world. The ugly can be turned into something wonderful. On the other hand, of course, I’m a part of the problem, because I’m one of those humans myself. If I went and did all my works in wood, it would be like a lie. Wood is beautiful, of course, more beautiful than anything else. I don’t want to fell a tree for my sculptures, though.

Another thing is that I find ugliness to be interesting in and of itself. Beauty is something that’s everywhere in the consumer industry, and that alone is a reason to mistrust it. I find it more exciting to take something that looks terrible and nobody would say is worth anything, and to make something out of it. Which means that the biggest value in the works is not the material but the time that has been spent with the sculpture. So, time is in fact the most important material.

Water relief, 2018. Styrofoam, acrylic paint, polyester wool

You said that beauty belongs more to consumerism. What about beauty in nature? Could we call the animal world beautiful?

I have a good friend who comes from East Germany; he grew up on a farm, with animals. One time we were talking about animals that I would usually call ugly animals. But he said that they’re such beautiful creatures. I couldn’t stop wondering what he found so beautiful about them, because they’re not nice looking for the casual eye. But beauty is about appreciation. My aim now is to see every animal as equally beautiful, instead of saying one is more beautiful than the other and therefore has the right to a better life. This is very much about values and seeing the dignity in those beings. Some of the ways in which the notion of Beauty is used are quite misleading. It’s something to rethink.

What are the main lessons animals have taught you since you’ve been working with this topic?

Many things. There’s one thing we can learn from animals, and that’s not to drink milk from another species. We’re the only ones who have this habit. To obtain milk, the mother cow is separated from her baby, which is very cruel. This happens everywhere and all of the time, but it doesn’t make the suffering any less when you separate a mother and child. Also, the milk industry and the meat industry are interwoven – they’re actually one industry. This industry is also killing our climate.

We rely on animals but are largely ignorant of them as fellow creatures. At which moment do you think we as humans lost this connection with the animal world, and is there any possibility of renewing it?

Now is the chance.

There was a general time in human history known as the Neolithic Revolution, when humans settled down and began to breed animals and grow plants, and a lot of problems started at that point. But if I look at things as a vegan, it’s again different, because before that time humans were generally hunters. I sometimes imagine an alternative life in history, without humans killing animals, and I think it’s a bit ahistoric in a way, of course. The history is different. But we would be able to sustain ourselves without killing animals, and this could actually be defined as something that makes us human. Usually people try to justify it by saying that predators eat meat and humans are also predators. Or at least omnivores. It would be real progress to define ourselves as the animals who don’t eat meat and who don't kill. If that were so, then I’d be happy to say that I’m a human being.

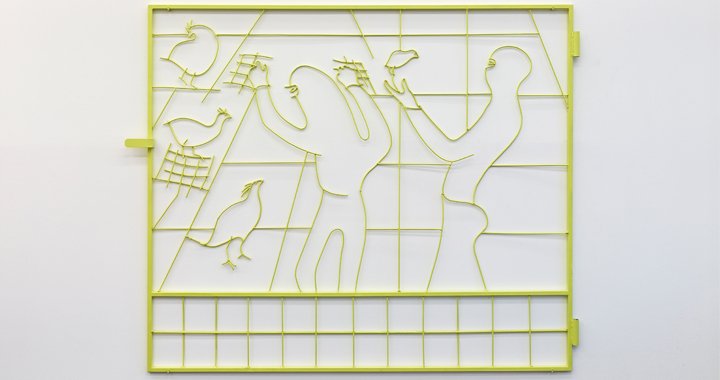

The Liberation of Animals from the Cages XVIII / Olifant Gate, 2016. Steel, varnish

Do animals need us humans?

Not in the past, but now they need us to clean up the climate mess.

Picture books about farm animals are probably the first books many parents give to their very young children, and this is a way in which they learn about human-animal relations. This is then followed by a visit to the natural history museum and the zoo. What do you think would be the right way to teach children about human-animal relations?

I see zoos ambivalently. Large zoo animals are under particular stress because their enclosures are too small, and they’re often sedated with tranquilisers added to their feed. Zoos also regularly “need” offspring, that is, the birth of young animals for public relations work. And what happens to a lot of the older animals is that they’re slaughtered. There’s so much to criticise about zoos, it would be worth a separate conversation.

Regarding children’s books, there are now some that represent an alternative human-animal relationship. In the German-speaking area there’s an initiative called Mensch-Tier-Bildung [human-animal education – Ed.] that’s founded by activists from the animal liberation movement, whom I appreciate very much and who offer workshops for educational institutions and for students of different age groups. When it comes to the future of the human-animal relationship, there’s nothing more important than the next generation.

Do you feel that your work has an impact? Do you as an artist have a voice that is heard?

I don’t really know. This is what we mentioned before, about art history and those hunting still lifes that legitimise the killing of animals. I want to show an alternative and peaceful situation. But we’ll see in the future; I think it’s a bit early to know whether things will change.

Have you ever felt that you as an artist were ahead of your time?

The people around me with whom I discussed animal issues around 2000 were ahead of their time and ahead of me. The animal liberation movement started in the mid-1970s. But it took a long time for me to develop; I find myself slow and late. Apart from that, there have been others before me, such as the British artist Sue Coe. I haven’t met her. But I admire her a lot.

Also, when you do things by yourself, it takes so long that you don’t feel at all ahead of time. I’m still thinking about the question you asked about why empathy is so rare in art. This is such a good question, and I ask myself this very often. There are a lot of musicians who have been vegans for a long time, but veganism isn’t so common in art. Of the friends of mine who are of my generation, almost nobody is vegetarian, let alone vegan. I have several ideas about that.

Between 2001 and 2006, when I finished my studies and before I began doing my art about animals, I spoke with colleagues, also women, and they warned me not to do this in my art, because I would not be taken seriously. Because it seems like a female topic, it was seen as something negative, and several times when I got studio visitors people looked at me as if I was a little kid, because I was interested in animals. Kind of like you won’t survive in this field because it’s a very soft and personal topic. Which I don’t think it is; in my opinion, it’s a political topic.

This also had to do with the “zero years”, the first decade of the 2000s, which are now also seen as a low point in feminism, for instance. A valley in one of the so-called waves, and apparently this applied to the topic of animals as well. Especially in Berlin, the zero years were terrible in this aspect. There was, for instance, a very successful gallery that was famous for showing only male artists, and this was not a secret, but people didn’t care or criticise the gallery at all. OK, there’s a group of guys and they’re successful and they sell all their works, but people went there anyway, and my artist colleagues also went to their openings and wanted to be their friends. When I asked, “Are you not angry that they don’t show a single woman?” the answer was, “Yes, but that’s their concept.” It seemed like a subliminal misogynic situation. During the zero years it wasn’t even worth trying to show a work about animals. It just didn’t make sense.

Now – and also in the context of gender equality discussions – we have a different situation.

The Liberation of Animals from the Cages IV, 2008. Installation with cut out / screed cardboard, transparent paper, wood, lit up from behind with strip lights

Why does society in general still strongly disapprove of vegans? Despite the fact that veganism has gone mainstream.

I don’t see that anymore. Vegans have been attacked massively in the past, but for years now nobody has asked me anymore why I’m vegan. I’d say that’s progress. An appreciation for veganism now exists. Of course, I live in Berlin, and this is a very open city. When I came to Berlin in 2003, I founded an exhibition space called Center, and I wanted to bring together the very different influences that I was seeing.

For example, people in Düsseldorf with whom I studied, they had a certain style, certain habits. It felt like artists in Düsseldorf considered themselves at the top of society, which I found problematic. I met a group of Russian artists in Berlin, and I found them surprisingly different. They were political, very leftist – the complete opposite of my Düsseldorf friends. I wanted to somehow bring those fields together, and that’s why I founded the exhibition space. But it didn’t work. I didn’t have a big budget. Düsseldorf artists came because they could afford the train ticket, but the Russian artists didn’t have money, and they only went somewhere if they were invited and their expenses were paid by some institution.

Why am I telling all of this? When I mentioned my animal topic to the Russian artists, they unfortunately didn’t take it seriously at all. Because for them it was just Western shit. Like a spoiled person’s viewpoint. Somebody said to me that as long as one human being is still in prison and has a bad life, we don’t have to think at all about animals. This, of course, is a very common way of thinking about animals, that a human being is more important.

Many great artists/film directors/musicians were already speaking about the issues of climate change years ago. But no one has managed to have as strong an impact in as short a time as Greta Thunberg. Why is that?

Greta Thunberg is part of a social movement, and social movements aim to reach as broad an audience as possible. In the art world, it seems that it’s the other way around, or at least it has been for most of the time. It’s about a specific small audience, and the last thing the protagonists of the contemporary art establishment are interested in is communicating to the broad masses. Exclusion – mechanisms that function through aesthetic codes – is much more usual in the art world.

An example: I wrote an article for an animal rights magazine about animals, especially live animals in contemporary art. And when it was published, I handed the issue to a very good friend and fellow artist, and I asked him if he’d like to read my article. He gave the magazine back to me saying that he didn’t like the design of the cover or the magazine’s typography, and that’s why he didn’t read it. And this has happened many times to me and in several forms. It’s often about aesthetic criticism, which is more important than the idea.

When I was studying in Düsseldorf, there was a predominant general style of communication that I would describe as a distant gaze, or an ironic postulate, that made it almost impossible to address political issues. Also, artists love to describe what their work is not about. Not what it is about.

The Liberation of Animals from the Cages III, 2008. Styrofoam, acrylic paint, wood, polyester wool

What do you think about the role of art in our society nowadays? Does it play any role at all?

One thing would be the general role of art, and the other would be how I would use it. I experienced that, for instance, on Königsallee when I distributed those leaflets against wearing fur – it was very difficult to emphasise a topic in this way. It can be a very imprecise way of communicating sometimes. You can see people immediately throwing away a leaflet, or handing it back to you with an angry comment.

With sculpture or my artistic work I can communicate how much this topic means to me. I spend my life doing these things and addressing the animal topic, which is one of the most important to me. For me, this is more adequate than practising another profession and at the same time trying to communicate the animal topic in my private time. Of course, the classic activist way of spreading information via print media, social media and “undercover recherche” is most important to inform people about animal exploitation. The rise of social media is responsible for the increasing numbers of people standing up for animals and going vegan.

You mentioned that the art world is still quite secluded, closed off. Right now, for example, you’re working on an art project that’s focused on a very complicated situation (politically, socially and also ecologically), namely, the so-called Mesopotamian Marshes, or the Iraqi Marshes – an area that was historically the largest wetland ecosystem in western Eurasia. It was destroyed during the regime of Saddam Hussein and later partially renewed, but nowadays the region is threatened by the construction of dams in Turkey. Do you think the message of this project will succeed in reaching a broader audience, or will it remain just in the circle of the art world?

I would be very happy if it reaches a broader audience. This water landscape in the desert is so unique, and hardly anyone has ever heard of it.

You asked about the innocence in my style. Two years ago, I was in Mexico, where folk art is a very important element of the culture. It’s done by many individuals, and it also has a big tradition. I saw several museums there devoted to folk art. At the same time, when you think of Germany and folk art there, it sounds terrible. At best, some old textile designs might come to mind. Art and the artist have a completely different role in the German cultural context.

It would be ideal if a work of art could communicate to a viewer without requiring cultural codes. Often art only speaks to specific groups that understand the codes written for them. This becomes very elitist, and I don’t want that. I like art for people who maybe don’t know the language, art that’s understandable without special cultural knowledge. That’s why I used writing within works that people cannot read. It turns the viewer into an illiterate person. I find this interesting as well, because animals are also illiterate and yet they still understand things, although we don’t know the extent of what they understand.

Two rabbits live here in my studio, and sometimes I wonder and fantasise about how an animal perceives the same situation that we are in. How do they perceive us? Do we make a complicated impression on them, or do they feel like it’s no problem at all?

Agri Relief, 2017. Styrofoam, acrylic paint, wood, steel, cord, paper

Do you think your rabbits are happy with you?

I hope they’re OK with me.

Do they understand that you’re fighting for their rights?

I don’t know. In any case, they don’t act like they know it!

Why aren’t people able to stop climate change? And what can be done to improve the situation?

You mean apart from going vegan, adopting and taking the train? For us who are participants in the art world, we should fly half as often and donate for our carbon compensation or, even better, let’s cut the art calendar in half. Turn biennials into quadriennials, more work in the studio, and we gain lots of time for other things. The question should not be “have you been there”, but “how did you get there”. For example, within Europe it’s possible to travel to the Venice Biennale by train, but who goes by train? It’s complicated. Also, I don’t think you have to go see every single event. I think climate change should not be a label. Hopefully we’ll be able to slow down man-made influences until there’s decisive technological progress.

Do you agree that art complements the nature of humankind?

Sure. But most arts are only important for people, which means that art is also completely anthropocentric. As far as I’ve seen, the only human art that animals like is some music.