Allowing the snowman to live

An interview with painter Ēriks Apaļais

If life had not thrown some completely unexpected hurdles in our way, young Latvian painter Ēriks Apaļais’ solo exhibition Ģimene (Family) would still be on view until March 29 in the Great Hall of the Latvian National Museum of Art. Right now, however, as elsewhere in Europe, all museums and cultural institutions in Latvia are closed, and Apaļais’ exhibition has unwittingly taken on a completely different context.

Apaļais organised the exhibition together with an impressive team: Katerina Gregos (curator of the first Riga Biennial of Contemporary Art, or RIBOCA), Astrīda Riņķe (director of the Alma Gallery, which has long represented Apaļais), designer Rihards Funts and the GolfClayderman group. And, as long as we’re listing names, we should also mention the special guests who show up here and there in the exhibition: Orson Wells, Andrei Tarkovsky, Marcel Broodthaers, Vija Celmins and Stéphane Mallarmé.

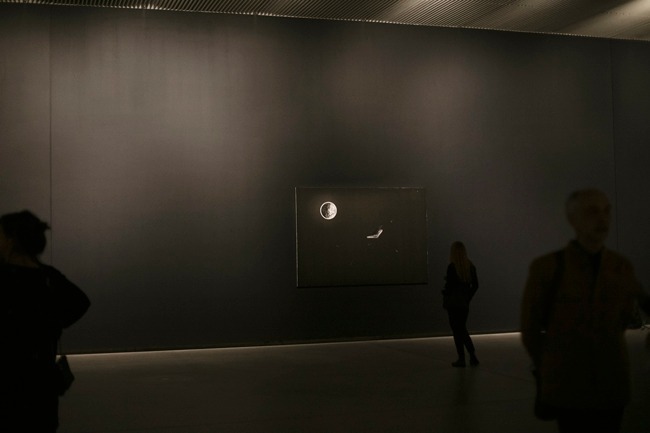

The impressive show is divided into several spatial and thematic sections that are seemingly well defined, although I have to admit that the actual boundaries between them are not obvious – just as it is not obvious to what extent the exhibition is a retrospective of a single artist and to what extent it is a very conceptual reflection with autobiographical dimensions. In any case, it seems that Apaļais and Gregos have put to use the museum’s Great Hall (the largest space in the museum’s basement level) in such a way as no other artist or curator before them has dared to do. His minimalist paintings are displayed only along the walls of the dimly lit space, allowing visitors to view any of them from a distance of three as well as thirty metres, thereby experiencing a bit of the cosmic void that seems so conspicuous in some of the paintings.

When I ask Gregos what initially attracted her to Apaļais’ work, she responded: “I was struck by his very distinctive and memorable ‘signature’ style: monochrome colour fields where figures and objects float in space and in which allusive, elliptical narratives unfold on the basis of minimal pictorial clues. It is not easy for a painter to create a unique visual language today, and Apaļais is one of the painters who manages to do so. His work gets under your skin and lingers in the memory for a time to come.”

Apaļais is an original and thoughtful painter of the young generation, which is, of course, a delight in and of itself. But these qualities are also confirmed by his success in the Purvītis Prize competitions, RIBOCA and elsewhere as well as his unusual ability to articulate his thoughts. “Unusual” in the sense that artists do not always stand out for being able to speak in detail and at length about their work – which is not, after all, their responsibility nor should it be. Bet Apaļais nevertheless demonstrates not only a clear ability to reflect about his work but also an evident and intense desire to do so, and the listener realises that, in this case, it is not a choice but rather an insurmountable drive on the artist’s part to analyse the process of his work, its motifs and its contexts again and again.

Do you yourself like the exhibition?

Yes, I guess I’m satisfied.

It’s a retrospective of your life as an artist as well as of your everyday life.

But I wouldn’t really call it a retrospective, although many want to call it that. I don’t perceive it that way. A retrospective is more about looking back on the past. Whereas here, the fragments of the past are linked with the present in order to underscore a single guiding line that… How to define it best? In any case, when Katerina [Gregos] and I met, she wanted to better understand what I was really interested in, in order to show my interest better. And then came the idea about the supposedly chronological sections, but it was never at any point intended as a retrospective.

And what is that single guiding line?

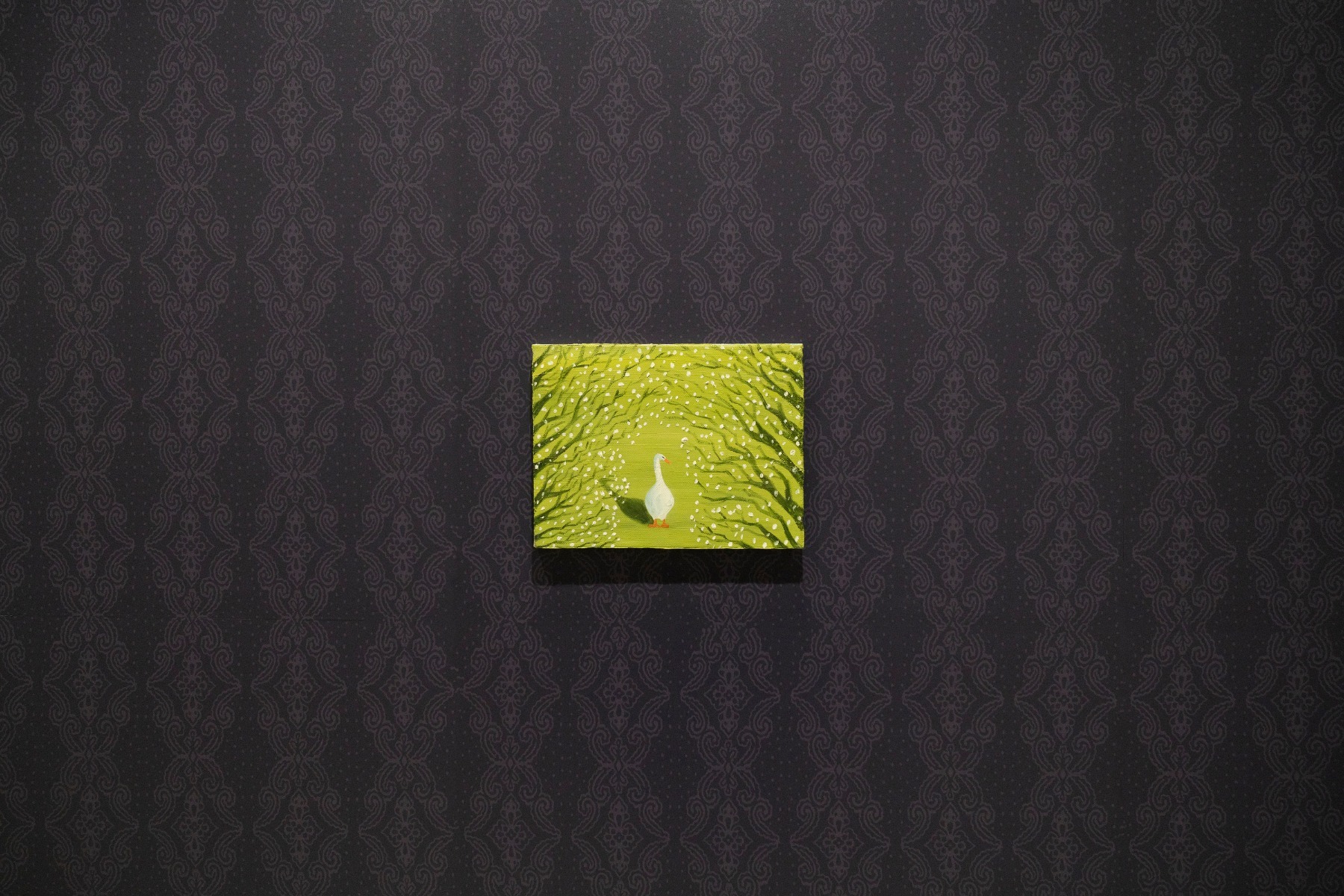

It could be called a process. At the very beginning of this process are the colourful works in which the image is fairly unified and in whose characters you can feel a kind of self-deprecating humour as well as a critical distance and also some kind of methodical approach. But the works were in no way fragmented; they weren’t deconstructed in any way. They were fairly unified.

Was the self-deprecating humour already there as you were painting, or did you notice it later?

Already as I was painting.

Photo: Toms Harjo

And approximately when did you make those works?

2006, 2007, 2008. And after that I moved on to the black, matte backgrounds with images that are in some way already taken apart, where the fragments are flying around. And then come the paintings – like in the “Tukums–Tomsk” section – in which I return again to the concrete, the specific, but now in a kind of different register. Because at some point when I was trying to take apart the images… Well, for example, a snowman. That’s an image that always pops up for me. And I project various meanings into that snowman image which aren’t directly linked with the snowman, because it’s precisely in him that I’m able to project this memory space in which I’m arranging all of those references (both autobiographical and in relation to art history) that I also have to take into account.

As I articulate my images after taking them apart, I end up looking around for new forms. But those searches aren’t spontaneous or expressive; instead, they’re linked with a specific brushstroke, with the way in which I apply the paint. When I apply the paint, it’s like a performative pattern, as if I were writing something by hand. But at the same time, as I’m painting I equate the writing to some kind of expression. The way in which a person applies paint has a kind of intonation; there’s a kind of intention there, something I want to say, and that’s when the path begins, the search for what it is that I want to say. And if what I want to say is linked with memory and images, a lot of crucial points appear: how can it be expressed at all, how to pronounce it, and so on. Accordingly, the intonation contains both an encoded or registered longing to say something sensible and a crucial motif. You could say that I’m creating an analogy between speech and the painterly pattern. While the abstract expressionists took words away from images, I try to somehow modify and adapt this mass of abstract language to my own interests and use abstract means to try to return to the specific. To objectivise the subjective, you could say.

For example, the painting with the water lily is supposedly specific, but I’ve arrived at it by following all sorts of roundabout ways. That is, after concretising the subjective it’s possible to paint a uniform flower. So, the work ends up being basically about constantly saying or writing something out, but as I do so the intention has already changed; something is transformed through the act of saying it. And at some point I just have to capture it, capture the multiple layers of the process by using the materiality of colour. There are lots of points of reference, and at some point they all somehow come together, and I capture that.

The great joy came in the fact that I was able empty the characters and look at language as something relative. Linguists who specialise in semantics usually look at specific meanings that we can all agree on, that we can describe and that are rooted in something somewhere. In this case, we agree that this or that thing has a specific name and we can ascribe this or another meaning to it. But there’s also the second level, which is difficult to define, which includes the individual layers, the personal experience, the mythological perspective, where words acquire subjective additional meanings. And it’s basically impossible to define those meanings. Or to measure them. Or to describe them. Difficult or impossible. I don’t know, at least it seems so to me. But maybe I’m wrong.

Photo: Toms Harjo

I completely believe you when you say that the way in which you apply the paint reveals the intonation that you talk about. But there’s some kind of untranslatability that always appears here, an obstacle between the artist and someone else. Can you try to explain the appearance of this intonation in more detail?

One example, which I’ve already used. When I paint a snowman, the bottom ball of snow emerges from a brushstroke that’s kind of like a figure eight. For example, if you look at paintings by abstract expressionists, I think for them it happens more spontaneously and more directly. In my case, I give expression the opportunity to express itself, but at the same time I also try to objectify it. I try to look at it critically in some way. As an utterance.

While it’s happening, or afterwards?

While it’s happening. At the very moment it’s happening. It’s a complex process. There’s the image, the snowman. I watch how it’s built, I look at the frame and the construction, I look at how I can deconstruct it. You can think that way about images or letters or other writing symbols – why they contain such and such a form and structure. A snowman it like a pictogram; you can perceive it as a symbol, and if it’s a symbol that’s based in my individual mythology, I can express it in some way through my own alphabet. Let’s say, for example, a brushstroke can be made with pressure, like this, or it can be geometric, made like with a ruler, where the hand is completely ‘neutralised’. And then it turns out that I’ve used the letters of my alphabet to express the symbol, and it’s something that’s visible and recognisable – a snowman. I could just as well paint pure abstractions, but that would be like… (Thinks.) I think pure abstractions would be too serious.

Is there seriousness in your paintings?

Yes, somewhat.

Photo: Toms Harjo

Would you go so far as to say there’s even humour in them?

It’s hard to tell. Humour is too fluid a thing to be defined so easily. It’s got something mischievous about it, but it’s not a joke, it’s not quick wit that can be easily understood and laughed about. I’m basically not interested in things that can be quickly understood and then easily forgotten. I don’t think it’s even possible to definitively and statically describe things like these images, which have these individual layers that grow word by word. And so, in my case, humour is a kind of attempt, but it’s an attempt that you know is bound to fail anyway. Nevertheless, I’ve been given all of these tools – tradition, creativity, something like that – and I’m able to put them to use in some way. But leave the definitive definitions to science. Art that can be described and concretised relatively quickly is problematic. In that case, I think art has already ended. The person doesn’t have a very developed sense of imagination, or else… There’s got to be some kind of abstraction in the thinking. Yes, I don’t know…

Is there any connection between the snowman and the fact that your name is Apaļais [‘the round one’ in Latvian]?

No, none at all, of course. (Laughs.)

Really? None at all?

Well, maybe a connection that I’m not aware of consciously.

Photo: Kristīne Madjare

But why exactly did the snowman appear?

Because while I was studying in Germany, I fairly quickly saw what contemporary art needs to look like, and…

Wait a minute. You “saw what it needs to look like” – what does that mean?

It doesn’t mean that I saw what good contemporary art is; I saw what contemporary art needs to look like. You can see what kinds of compositions are usually used in a space, what kinds of materials are used, what kinds of media are mixed, what kinds of references to larger movements are made and what short appropriations or insertions are used, or, in response to that, what sort of interpretations or materials were in fashion at that time. And when I saw all that, I understood that I do not want to make that kind of art. It’s hard for me to say so about myself, but I definitely didn’t want to create…

It’s said that originality in art is, on the whole, a concept that has transformed itself so many times that nothing can be said about it anymore. ‘Original’ was once considered something good, then it was something bad, because it was associated too much with the cult of the genius, and appropriation artists tried to not be original but actually became original precisely because of that – there are so many possible modifications, but in the end, the teachers who told us about all of this nevertheless expected something original from us, their students. In the sense that you can’t just make something that looks like a contemporary installation, in which you prop something up against a wall and write a text that says “the viewer is looking at this, and the meaning is in that look” or whatever. These standardised approaches…

My teacher was Andreas Slominski, who imparted a great deal of information through his presence alone. All he had to do was say three words to me, or just look at me, and I already received so much information that I… I really soaked it up. And in our theory seminars I realised that people can think and speak interestingly, but the people who think interestingly aren’t always the ones who make interesting art. The fact that you understand theory well doesn’t always mean that you’ll be able to make an interesting work of art. I caught on to that very quickly. School tried to stimulate us to search for our own type of interests. To search for what actually interests me as a person. Me or other people – what is it that actually interests? And interests can be very diverse. For some it was simply a kind of lifestyle – you go to school, you do a little bit of this or that. Others were very refined, really knew a lot and were very talented in their work. Then there were those who had a lot to say but were perhaps too limited, too constricted. I was lucky in the sense that I had very knowledgeable people around me whom I could learn from. Both fellow students and teachers.

Photo: Toms Harjo

How did the idea of this exhibition begin? How did it come to fruition?

Katerina Gregos had already seen my work at the Alma Gallery before the first Riga Biennial of Contemporary Art. She knew Astrīda Riņķe, who has participated in Art Brussels. Apparently Gregos was intrigued by that one large-format work of mine displayed at the Alma Gallery when it was still located on Rūpniecības iela. Then she invited me to participate in the biennial, and later, when we met for dinner, we got the idea of developing this sort of collaboration. We took part in an open competition for projects, won and got the opportunity to organise an exhibition.

You’re not even forty years old, and you already have a solo exhibition in the Great Hall of the Latvian National Museum of Art. Do you feel a sort of tingle of responsibility? You’re now an authority figure for life.

Any solo exhibition, no matter how big or small, instils some anxiety in me. Most of the artists I know get very anxious and worried before exhibitions. If I only showed you what some of them have written to me before opening days… (Laughs.)

Photo: Toms Harjo

The exhibition description contains a very predictable reference to “Freudian quality”. That doesn’t bother you?

I think Katerina mentions it very cautiously. I was in fact reading Freud when I painted my naïve works. I was reading about his concept of Das Unheimliche. I don’t know how to translate it – maybe ‘eerie’, or ‘uncanny’? It contains the root heim, which means ‘home’, and heimliche is something that must remain secret, hidden. And then the negative prefix makes it an antonym to what is homey and hidden/secret. It’s what’s suddenly come out, to the exterior, and turns out to be eerie. It’s a feeling between hominess and uncanniness. And I think that’s exactly what appears in those works of mine.

And then there’s the concept of Deckerinnerung, which speaks about memories that may be hidden or concealed. If we take the snowman again – what’s so interesting about a snowman? It’s so undistinguished, so common, so popular, seen on all the Christmas cards. But why exactly a snowman? And that’s partly where the humour lies – sometimes I consciously use symbols that are hard to solve. As Ruta Čaupova once told me, “You’ve taken that snowman and settled him into a sort of metaphysical space, allowed him to live there.” (Laughs.) How does one settle a snowman into a metaphysical space so that he’s allowed to exist? It would be a space in which you couldn’t critically catch the snowman doing anything, I don’t know, improper… That’s the mischievousness. If I just painted a decorative snowman, everyone would just say ha ha, someone’s painted a snowman. But if, while painting the snowman, you think about intonations, pronunciation, memory and childhood, then it’s clear that the snowman isn’t just a snowman anymore; it’s much more.

In his memoirs, Freud wrote about a patient of his who always remembered a bucket of ice placed on a table, and the patient couldn’t understand why he always remembered this one specific image. Why did he always see that bucket of ice? Gradually he remembered that his grandfather died around that time, and his gaze at that moment had fixed itself specifically on that object, on that bucket of ice. And that memory acted as a lid on an experience that he didn’t want to remember, didn’t want to think about – the object suddenly became a lid, something that covers up. But memories can also sometimes be completely imagined. I’ve experienced it, too, and only with a lot of effort do I understand that what I remember is in fact something entirely constructed by me.

“The virginal, vibrant, and beautiful dawn, / Will a beat of its drunken wing not suffice / To rend this hard lake haunted beneath the ice / By the transparent glacier of flights never flown?” [translation by Henry Weinfeld] Do you have any idea what this lake is and why it must be rended open?

Well, many people have written about Mallarmé.

But I asked about what you think.

Why do I like Mallarmé in the first place… I now feel like I want to return again to that unified image I spoke about in the first section, but which is followed by the black works in which everything is sort of fragmented. Mallarmé also spoke about fragmentation. But I also saw a kind of big dead end in him. I’m not really sure whether that’s a solution.

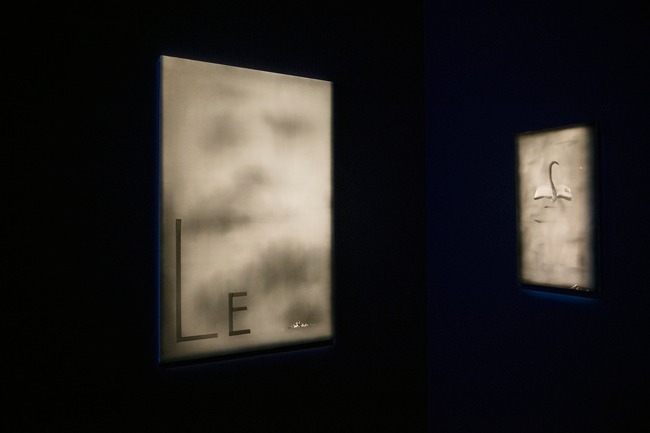

Photo: Kristīne Madjare

What’s not a solution?

How can I say it? Before Mallarmé, Romanticism constructed metaphors that contained analogies between the processes of the soul and processes in nature. For example, “nature is the mirror of the soul”. I watch a stream flowing and feel a process taking place in my soul. That’s a metaphor that you read and think to yourself, “Ah, how beautiful!” There’s a stream flowing within you, and you feel good.

But Mallarmé takes that same metaphor and looks at it critically, both the stream itself and the structure of the metaphor. He takes those nouns of nature used by the Romantics – the mountain, the stream – and looks at them already as culturally created constructs of sorts. And then he takes those words – which also have gone through certain processes, certain paths by which they have been created and gathered meanings that we agree on and that form the conceptual frames through which we understand things – and Mallarmé arranges them on the page in such a way that the meanings are no longer linear. For example, if a person believes in God, he can project very much onto the unknown. He can strive for the unknown, he can trust in the unknown, he’s got a lot to work with there. But then “God’s head was chopped off and the sun fell to the earth”. Now everything’s on the same level, on the same surface, in terms of usable material. It’s no longer possible to project your own longings onto some phantasm or illusion; you come to realise that it’s all a man-made construct.

And, basically, I think his poetry is about… Well, the swan is the one who would like to rise, to soar away, but it’s no longer able to do so because the opportunity is not there. The swan is just a sign; I think Mallarmé even refers to a black swan. A black swan frozen in a lake – a symbol frozen on a piece of white paper. The written and the said, even if they are metaphors, are self-critical metaphors, and they don’t make you gasp with joy; instead, they’re more likely to drive you to despair. Because you understand that everything’s out there on the surface and everything’s frozen. And language is just a material, just a construct; you can’t project anything onto it. No illusions, because those can be critically examined as well.

There was a period when I supposedly understand all of that, but something in Mallarmé’s ideas didn’t fully convince me. After all, we can imagine an alternative situation in which, even if it’s all a construct, you can nevertheless take the elements and… for example, equate God with a button. Actually, you can take practically anything and turn it into some kind of meta-element, find some kind of thrill in the interplay of the many elements that have the potential of meeting in their trajectories. I’m interested in and perplexed by the fact that any element can potentially become something. You can equate something really full-blooded, deep and well thought out with something completely flat, and there’ll be an equals sign between the two of them. Mallarmé supposedly has this element of play, but it seems to be at a stage that could still be modified or developed a bit.

Does this possibility of equating anything with anything worry you?

It doesn’t really worry me. It perplexes me.

Perplexes.

Yes, because there’s something… (Thinks.) Well, no, there’s also something good in it. Through this sort of approach you can liberate yourself from authorities, traditions, various dogmas. I’ve done that to a certain extent in my “memory object” works. But there’s also a downside to it – you relativise it all, and then you realise that you’re just, like, “what?” The answer to that might be a game or returning to the unified image, in which you then try to meld all of the fragments and separate elements back together again.

Do you take notes when you paint?

No, not particularly. There’s no time to do that while painting; it’s a pretty intense process for me.

Photo: Kristīne Madjare

Do you plan your painting?

What do you mean?

Well, you have status as an artist. You make new works of art from time to time, you’re a professional. Do you plan your painting process like you would a job that needs to be done every day?

More likely not. I’ve tried to do that, but I understood it doesn’t work for me. I once tried going to the studio and painting regularly for a whole month. I did about a dozen or so paintings in that month, of which one was good. (Laughs.)

So what’s the alternative to an approach like that?

That I go to the studio when I’m inspired. Of course, if I’ve got a show coming up, I go more often. But on average I paint about two or three paintings a month. Of course, the process doesn’t involve just the actual hours I spend painting – it’s always going on in my head, too.

Do you plan to continue and develop the “Tukums–Tomsk” section?

Well, we only exhibited some of the works in this section, about half of them or less. But right now I have no plans to continue working on it. I’m painting other things now. But maybe I will in the future. I don’t know.

Tell me about your long and successful collaboration with the Alma Gallery.

Well, I can definitely say that the relationship between an artist and a gallerist is very complex. That’s usually what artists say. It’s a bit of a power play, and you also develop a personal friendship… But Astrīda Riņķe is a person who really loves art. She’s not a gallerist who thinks primarily about how to earn money. Katerina is the curator of this show, but Astrīda can definitely be called the co-curator. She has a very sharp eye, and lots of the details in the exhibition were her decisions. It’s pleasant to work with her, because you see that she’s genuinely interested. If a gallerist is alienated from art and you talk to them like you would with a bank teller, then it all just right away seems useless.

Photo: Toms Harjo

And what is it that you’re interested in right now? Besides art.

Lately, I like flowers and the sea.

Flowers and the sea…

They’re similar to snowmen in the sense that you should never paint flowers or the sea. I could perhaps even envision an exhibition on that theme.

Ēriks Apaļais. Flowers and the Sea.

Well, maybe the title would be different. (Laughs.) More likely it could be about some kind of… Not that I’ve now lost my mind and have started painting flowers and the sea. No, I’m interested in flowers as something that you’re supposedly not supposed to paint. Well, obviously, everything is allowed, but in the art of today it’s very important that you thematise something like flowers. Flowers and the sea as capacious and meaningful symbols that the art market could thematise – in the context of Romanticism – through, for example, Charles Sanders Peirce’s classification system. As things that I could contextualise at a meta-level as a single, unified image.

Alright, Ēriks, thank you and good luck!

Photo: Kristīne Madjare