Is there such a thing as the idyllic village?

A conversation with the Polish architecture collective PROLOG +1

My conversation with the architecture collective PROLOG +1, which is curating the Polish Pavilion at the 17th International Architecture Biennale in Venice, took place on March 5 at the Zachęta National Gallery of Art in Warsaw. It is precisely this institution, which is one of the most significant sites and points of reference on Poland’s cultural scene, that organises the country’s representation at the Venice Architecture Biennale. And it was on this very same day that the biennale announced it would postpone its opening until August 29 due to the disruption caused by the COVID-19 outbreak.

PROLOG +1 is a group of architects (and in this case also curators) established in 2017. The founding members – Mirabela Jurczenko, Bartosz Kowal, Wojciech Mazan, Bartłomiej Poteralski, Rafał Śliwa – decided to band together because, as they say, “if a project is discussed in a non-hierarchic group, the result is less subjective, covers more problems and more likely will be accepted by the wider audience. ” Robert Witczak has now joined the group as well, in connection with the biennale exhibition. All of the members have at one point or another studied architecture at the Wrocław University of Technology, but they are now spread out across Europe, each in their own city.

Trouble in Paradise exhibition identification. Graphic design: zespół wespół. Polish Pavilion at the Biennale Architettura 2020.

Even before the COVID-19 crisis, the PROLOG +1 architects’ main mode of communication has been virtual. In Warsaw – on one of the rare occasions they convened in person – four of them met with Arterritory.com and, between our various train and airplane schedules, we found a couple of hours to talk. Ten days later, on March 15, Poland closed its borders.

You’ve put rural areas at the focus of your project “Trouble in Paradise”. Why have you centred your attention on the countryside? What is the message you wish to relay?

Wojciech Mazan: It was important from the very beginning to try to find new ways to describe the subject that we are talking about. And in this case, the name itself is a point of reference. We wanted a title that is a bit more descriptive and that tries to recognise the condition that we are seeing. So for us, the paradise part of the title can be read to some extent as something that the countryside was and might be.

Polish society has an idyllic image of what the countryside is. At the same time, it doesn’t really recognise the change taking place. If you get outside into the Polish landscape, you cannot really tell whether the country’s image is homogeneous or not. It is rather a kind of mix of various factories, various faces of the development of the villages. Basically, it is not very coherent, unlike what you would see in a Swiss village, in a Portuguese village or in a Spanish village. And this poses the question of whether we really have a good image of the countryside or not, because most of the time people have this connotation of the idyllic image, this connotation of paradise.

After the collapse of the communist era, Poles wanted to move to the countryside in order to seek out opportunities to realise their own potential, their own individual needs. But the global market is increasingly changing this rural landscape. People are not taking into consideration the possibility of planning and of particular legislation in order to control what is happening in the countryside. I mean, it is obvious to everyone that life in cities needs to be organised. People need cities to be well organised. So, there exists certain knowledge in this regard. In fact, there is huge knowledge behind the planning of a city, but at the same time, if you look at rural areas and villages, this process was more intuitive. They were developing, you know, in a kind of customary, traditional way – a father would teach his son how to build a house, and so on. This had been the normal way of transferring knowledge from generation to generation. Very intuitive. There was no planning, no set of tools for how to do it. And... We are trying to look at this body of knowledge and trying to find tools we can use to talk about architecture in the countryside. Because we simply don’t have them.

Rafał Śliwa: It is a question of what the countryside is. Because there are different definitions of it. I mean, ask yourself whether the countryside is just everything beyond the urban environment, or is it actually a settlement. A human settlement. A kind of collective endeavour to live outside in some small organic way. And if you look into the history of the development of the countryside, it seems to be only quite recently that we have begun to talk about this being an environment that might be used differently than just for agriculture. If you look at more recent history, you notice that we have never really discussed whether the countryside is actually just an open space beyond the city, or is it a precisely defined area in which we are supposed to live in a certain way.

So for us, the paradise part of the title can be read to some extent as something that the countryside was and might be. And trouble can be interpreted as the current context – problems that we are seeing within the countryside.

Bartosz Kowal: If this idyllic village... Does it even exist? Are there any problems looming on the horizon? We see some problematic forces appearing, but they may not yet be visible to everyone. And maybe that is motivation to see the countryside as a paradise. Maybe we just need some small changes in our thinking to get this paradise back.

Polish society has an idyllic image of what the countryside is. At the same time, it doesn’t really recognise the change taking place.

Wojciech Mazan: It always somehow goes back to this dichotomy between urban and rural. And this is something that we struggled with from the very beginning. In the case of Poland, 93% of the entire country is rural. ‘Rural’ is basically defined as everything that is not a city. Which in fact shows the problem – that we don’t even understand who we are. We don’t really have a proper understanding of how to call this 93% of our country. And that is exactly why we decided to use this exhibition to look and focus on the countryside, to move beyond the city and try to develop a set of tools, methods and ways to describe and understand what the countryside is for us.

You are asking about the future of the countryside... It is important to say that the whole endeavour for us starts with the general post-socialist context. So, what we see from more or less the mid-1990s onward is basically a shift in the migration pattern from the countryside to the city, which we had observed for fifty or so years after the Second World War. Beginning in the mid-1990s, the numbers of people going to the city stagnated to some extent. And in some cases we even saw a retreat from the city towards the countryside, which is basically the opposite direction to what was going on in the rest of the world, which was and still is urbanising.

So, we crossed the 50% mark of urban versus rural...and then what do we see here thirty years after the transformation of 1989? We are still seeing internal migration from the city outwards. It is interesting to look at it. If you look at different contexts that have tried to describe the countryside, they always follow the storyline that the countryside is depopulating and what are we going to do about it. In our case, I think the context is a bit different. And that is why I think for us it is quite relevant to look at the countryside, because we are not fully aware of this dynamic from the city towards the countryside. We are not recognising it, and we don’t have the tools or methods to describe it. This brings with it, of course, challenges but also some opportunities.

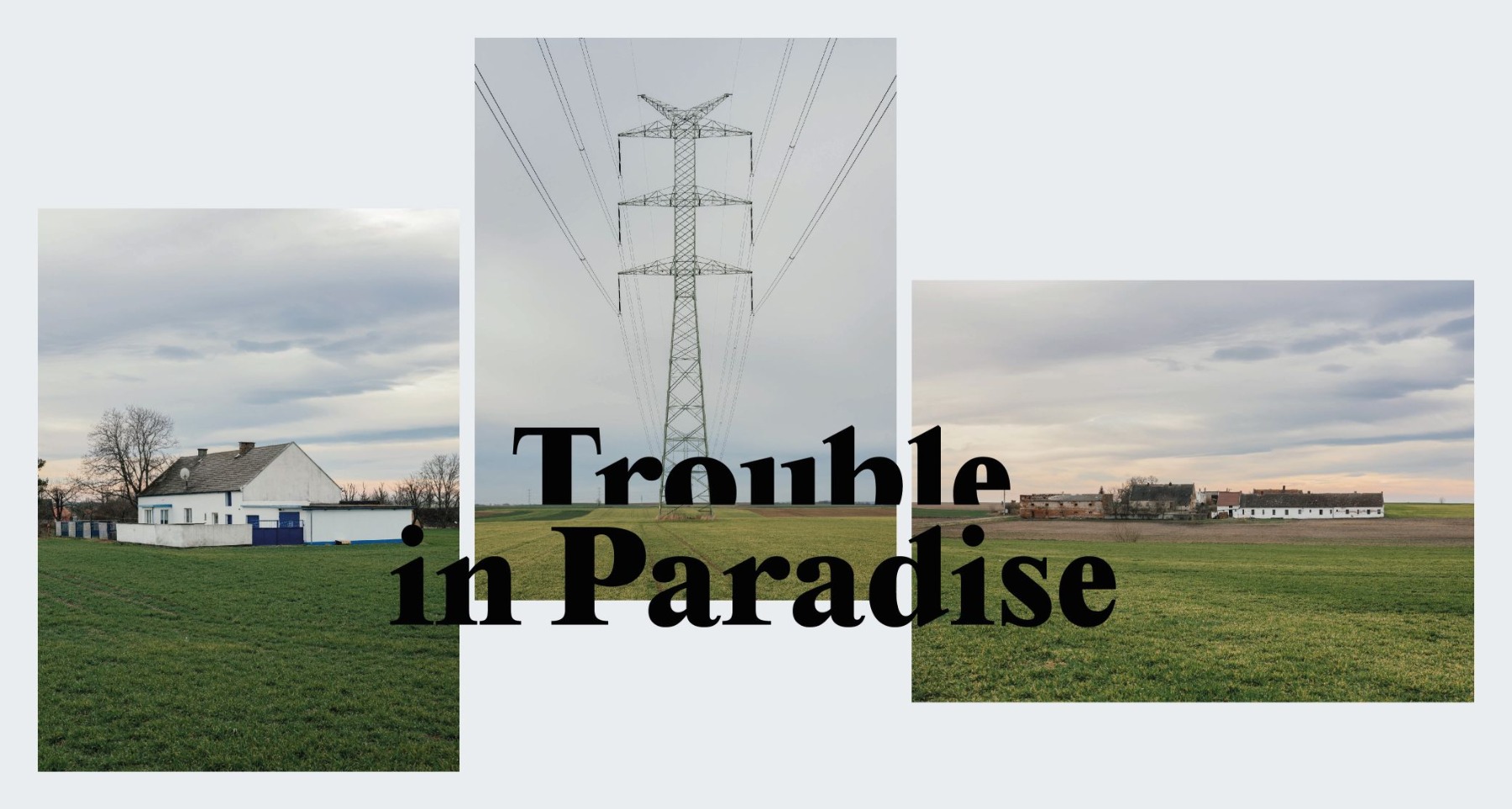

Dwelling–Territory–Settlement, 2020. Analytical part of Trouble in Paradise exhibition. / Photos: Michał Sierakowski. Polish Pavilion at the Biennale Architettura 2020.

But the world of architecture has always had closer ties with the city than with rural areas. Has architect’s role changed in today’s world?

Wojciech Mazan: Yes. The difference between what we see in the city and in the countryside, we are basically being challenged to look beyond our own profession. We are sitting here and talking about architecture from the perspective of a curatorial team, how we are seeing the profession moving forward, meaning that I think we have to be more fluid, we have to change the boundaries of what was formerly conceived as architecture. Because some people would argue that what we are looking at is actually not even architecture but planning, which is a different discipline. For us, however, they are still somehow linked. I mean, being responsible for an exhibition, looking at the scale of a building, looking at the scale of the environment... For us, all of these endeavours still subscribe to today’s view of architecture. The architectural method, or the tools that we are able to use as architects, are still helping us to deal with these problems.

Bartosz Kowal: We believe that people influence things, such as architecture, and this is also what we are trying to address in our exhibitions. For example, what the family looks like influences house design. And we also seem to believe that this house should stand physically close to another house, in other words, it should create a kind of settlement. And this settlement, in turn, is set in a specific environment. So, from this very first small decision – how people design their houses – to learning about how those people are going to live. And step by step these decisions influence the whole environment. Looking at it from other direction, by first focusing on the environment, you still return to exactly the same place.

Rafał Śliwa: The question about the role of the architect... That is not something we have a simple answer for. The role of people today can be defined simply from the perspective of how relationships between people are managed. Of course, they were different a hundred years ago, and they are different today. Likewise, they will be different again tomorrow. But for occasions such as the Venice Biennale, we would like to open up the conversation to see the possibilities of an architect as a person who can propose different ways of managing things, different ways of ownership, different ways of establishing social contacts. And all of that precisely from the fact that architecture is knowledge about ways of living – about how people lived, in terms of architecture, a hundred years ago, fifty years ago and today. And that is exactly what we are trying to clarify. It is a cross section of the Polish countryside. From looking at the ways of living over the past hundred years, you can tell precisely that the forms of living that we are proposing today may actually involve entirely different disciplines. And so then the question of the role of the architect is no longer the same as it was, say, twenty years ago. We are no longer designers, right? We no longer give just utilitarian answers. It is impossible to simply write a kind of handbook for how to do things.

It is interesting to observe the countryside phenomenon, because it hardly exists anymore in the classic understanding. The countryside is actually agriculture, and agriculture is the starting point for the class society, no matter whether we are talking about workers back in the socialist era or the middle class of today.

The world changes, and yet this is a difficult, painful process. It is not so easy to change human nature, to switch things around.

Rafał Śliwa: Isn’t it like this, though, that the first thing you want to do is actually sit down together at the table and see how things are? You can use dialogue. There was a very nice poster about this during the Second World War. There were so-called victory gardens in the United Kingdom, and there were beautiful posters about how to engage people in gardening: “You can use the land you have to grow the food you need.” And basically, if you start from this very simple observation of looking at what you have around you, what people are around you, you can engage in the community, in the common spirit. And there are also different, new ways of managing economies today, with countless examples, such as Airbnb. People share necessities with each other, they exchange things for what they need... It is the time of the shared economy. The cities have learned this, so why not the countryside, too? If we can engage people from the countryside in this discussion, then you can see that everyday contact – the real contact between people – is actually even better in the countryside than in the city, because they live in a small community.

Wojciech Mazan: I would like to add that, within this exhibition, there is the part where we are analysing things and the part where we are trying to propose strategies for the future. First, we have to sit down at the table and understand things. So, what do we see from the one hundred years of history that we are analysing? We see that we are looking at the countryside through the lens of three specialties: the environment, the settlement, the dwelling. What do we see over these one hundred years? We see a tendency for one of these areas being, let’s say, the leading one. There were always projects imposed on the countryside, projects that began either with the larger environment, such as vast attempts at nationalisation, or they began with plans for a specific settlement, or they began with a specific project in a socialist country for what the family should look like. It always somehow pulled to that one direction and tried to impose a totalitarian project of sorts on the countryside. These things never began in the countryside and moved outward, and they usually never looked at all the aspects of the project simultaneously. So I think that the path towards the future for us is to be aware of that.

The project has, first of all, tried to challenge the conditions that we see. And what do we see currently? Basically, we see quite drastic isolation in the countryside. But we would like to challenge this. And for us, the path to challenging it is to basically take an overall view, to look at the project from different scales and to try to somehow develop it, starting from the qualities that are characteristic to the countryside.

Robert Witczak: Trouble in Paradise... Why is this... I would say sexy. It captures the dichotomy that is very present but actually misleading. We live in a world of dichotomy between crisis and hope/promise, between the public and private, between rural and urban, but this actually doesn’t help us to understand the situation. So, what we wanted to do is position ourselves between those dichotomies. As an architect, I would now somehow sort out the clichés, the stereotypes of living in that condition of dichotomy. But it is interesting to observe the countryside phenomenon, because it hardly exists anymore in the classic understanding. The countryside is actually agriculture, and agriculture is the starting point for the class society, no matter whether we are talking about workers back in the socialist era or the middle class of today. These classes are actually imposed on people by a kind of economic situation, a situation that forces them to live in a way that serves the economy.

We would like to look at the commons – not only as a source of resources but also as a set of rules, laws and practices. We are asking the participants, the project teams in our exhibition, to find those commons – those resources and practices in the countryside. We would like to answer the question of how we will live together without the public and private situation that is very present. Maybe it is not so visible in the city, but it is more vivid in the countryside.

The biennale takes place in Venice, a city that shows clear evidence of the climate crisis as well as the effect of mass tourism, which does just as much damage as the aqua alta. Your exhibition, which conceptually refers to the global climate crisis, will also be part of the mechanism that is slowly destroying this city. Does this contradiction not trouble you? How do you justify it?

Rafał Śliwa: Yes. But, you know, how otherwise can you do it? History actually shows that knowledge has been made and disseminated through exhibitions. For example, if you think about the Paris exhibition from the past century and from over 150 years ago, it was a great endeavour to show knowledge. This is a hard question to answer, because there has been a history of doing things like this in the past century – trying to speak to the masses instead of limiting knowledge to the universities. And it has worked. Actually, it is becoming more and more popular in terms of learning, in terms of opening opportunities to say things. And isn’t it so that we still need places to speak, we still need places to meet, we still need places in which to engage with others in person? Digital media don’t allow us this sort of communication. I mean, we (our team) is trying to do this. Basically, every week we have a Skype session that somehow ends up stretching to five hours long. It is a long time, and we are all exhausted by it. At the end of the day, though, we see that every in-person meeting we have is much more consistent and much more effective than any Skype meetings we do. And, being aware of all this, we realise that real-life contact between people is crucial in the context of the exhibition. It is crucial for learning and sharing.

Bartosz Kowal: I think there are worse things happening in Venice than the exhibition. Such as the cruise ships and tons of tourists who just want to visit Venice to take two or three photos of the city on the water. Venice is a venue for discussions about art, about architecture, about dance and all of this. I think this is a perfect place. The exhibition is a good thing.

Rafał Śliwa: Of course, big events like the biennale are full of contradictions.

Bartosz Kowal: I think we are maybe trying to change things in some way. I mean, instead of showing the newest Polish achievements in architecture, we are asking questions about life in the countryside and about the happiness of people living there. We ask normal questions that are relevant to normal people. We are not following fashion or ambition. We are just trying to do something that we think has potential and is kind of missing from the discussion. We want to talk about a normal problem.

I am just saying that under radical circumstances we really are capable of changing things.

Yesterday the European Union adopted the Green Deal, which stipulates that we must reach zero CO2 emissions by 2050. It has already received much criticism for being too slow. It has been accused of failing to act...

Wojciech Mazan: Well, carbon dioxide has been reduced by 25% due to the coronavirus outbreak. But that is a rather drastic way of doing it, right? I mean, of course, it is possible. The question is just are we willing to go for it? I am just saying that under radical circumstances we really are capable of changing things. In the early 2010s we had the huge eruption of the volcano in Iceland. The combined carbon dioxide that was emitted from the volcano was still lower than whatever would have been produced by all the planes flying within that period had they not been grounded. So, we are able to radically reduce emissions. I think it is just that we are still somehow oblivious to the crisis that is coming.

Bartosz Kowal: So-called hedonistic sustainability is quite popular. In a way, we would really like to live our lives as we used to live and just find technological solutions that allow us to not change anything... If people don’t believe that things need to change, it won’t happen.

That is greenwashing – people reducing their responsibility for the ecosystem by making a contribution that actually doesn’t change the situation.

Rafał Śliwa: I think it is more up to the state than it is to us. You know, we drink coffee, and then some percentage of the profit from that coffee goes to institutions that are promoting this kind of problematic situations in the world. And you know what? This is precisely the same system that is putting guilt on you as a consumer for what’s happening.

Bartosz Kowal: You pay a few euros more when you buy an airplane ticket in order to decrease the carbon footprint of your journey. So, we are paying more and feeling released from the responsibility.

Robert Witczak: That is greenwashing – people reducing their responsibility for the ecosystem by making a contribution that actually doesn’t change the situation.

Wojciech Mazan: It is basically another way of defining everything by the market, right? I mean, if there is a will to look for green solutions, the market will find a way to capitalise on it – simply by adding a euro to your ticket, by adding fifty cents to your coffee to make it “greener” and for you to feel a bit better. But again, this goes back to that what we should be advocating in the exhibition – trying to look for the new centrality that we would like to have as the structure for our path towards the future. Right now the driving force for everything is simply capitalism. If only we were willing to release ourselves from the regime of the market and accept that things would be shared equally among people...

What I want to say is that with our project we are at least trying to be aware that the current condition is problematic and that we should look for ways to challenge it. It is important to change our behaviours, but in the end, I believe (and I would argue for this) that we have to try to change the whole thing...

Robert Witczak: Sustainability doesn’t affect only the environment. It affects all aspects of life, also the economy, culture and social life. Everything is interconnected.

Prolog +1 (authors of the Trouble in Paradise exhibition in the Polish Pavilion at the Biennale Architettura 2020). From left: Rafał Śliwa, Robert Witczak, Bartosz Kowal, Wojciech Mazan, Mirabela Jurczenko, Bartłomiej Poteralski, 2020. Photo: Paweł Starzec.