Our role is to emancipate the imagination

Interview with Maria Vilkovisky and Ruthia Jenrbekova, the founders of Krёlex zentre in Almaty

Airi Triisberg

Krёlex zentre is a conceptual artistic para-institution founded by Maria Vilkovisky and Ruthia Jenrbekova in Almaty, Kazakhstan. Krёlex zentre produces a wide range of cultural activities, including exhibitions, performances, sounds, images and texts. The imaginary art institute also publishes Shalazine, a journal on contemporary art, activism and subcultures in the post-Soviet region. The conversation with Maria Vilkovisky and Ruthia Jenrbekova is focused on the intersections of cultural activities and movement politics in Kazakhstan. It was produced as part of the research project by Airi Triisberg which is reflecting on the political biographies of artists, cultural workers and political organisers in Eastern Europe.

I keep asking one question from the people I interview: How did you become politicised? I find the answers very fascinating because they connect personal narratives with larger political histories, and pinpoint tensions or conflicts that exist in different social contexts. I would like to start our conversation with that very same question. How would you describe your trajectory of politicisation as artists?

When we started to practice as artists, the artistic milieu in Almaty was very depoliticised. Politics was usually considered somewhat dirty. Art was supposed to deal with broader issues, such as human values. This attitude was quite characteristic for post-Soviet countries in the late 1990s and early 2000s.

In 2009 artists Alexander Ugay, Elena and Viktor Vorobyev and curator Yulia Sorokina started organising regular meetings of artists in Almaty. This initiative was called Hudsovet, which roughly means Art Board. The format was imported from Ukraine, originally it existed in Kiev where it was led by Nikita Kadan and other artists from the R.E.P. group. For us these gatherings gave the initial impulse to start thinking more politically. The situation of collective discussion was already very thought-provoking in itself. Hudsovet was one of the first examples of self-organised and artist-led initiative in Almaty. The connection to Kiev was also important, we were sometimes discussing over Skype about political processes in Ukraine after the revolution in 2004/2005.

Upon joining the Hudsovet, we realised that our local art scene is full of highly contentious issues, and in order to sort them out it is necessary to read. We started to read various theoretical texts, and as far as we remember Walter Benjamin was particularly important at the time, so we reflected on his ideas about aestheticisation of politics and politicising art. We decided for ourselves that, as artists, we will need to do art politically: to do aesthetic things but with certain political meaning. We avoided direct political message, it seemed too bold for us. In 2011 we made an interactive post-Cagean event, which was somewhere between musical performance, lecture and happening. We were thinking at the time that an open participatory form of this event was in itself political and it would be excessive to include any direct political message. We felt that an art work can be political just due to its form. Later our understanding became more complicated.

We decided for ourselves that, as artists, we will need to do art politically: to do aesthetic things but with certain political meaning.

In the spring of 2012 we took part in the contemporary art festival in Bishkek and during this trip visited the newly established ШТАБ/ Stab (School of Theory and Activism Bishkek). We went to their office together with a group of other artists from Almaty and our discussions with Georgy Mamedov and Oksana Shatalova, the founders of Stab, were all about politics. Stab was explicitly leftist and queer-feminist platform. It was our first encounter with an openly political artistic organisation.

How did you feel about that?

It was very thought-provoking for us. After returning from Bishkek we had lots of things to read and reflect, we came back with a list of theoretical literature. In autumn we went back to Bishkek for one month as participants of Stab residency programme. This residency was a turning point for us. Our first presentation as collective of krёlex zentre took place in Bishkek. There was a lot of interest from the audience, we were not used to that. We were talking about creolisation in Central Asia. It seems that such conceptualisation of ourselves – not in terms of ethnic or national groups, but in terms of creolised and mixed “new” identities – touched a nerve. In Central Asia, many of us come from mixed families and have more than one identity.

Katya Nikonorova, The 8th of March Triptych. Image from the Second Sex exhibition, 2013. Photo by Krёlex zentre

In 2013 you organised two exhibitions around feminism and gender issues in Almaty. What was the context for those projects?

For us it was a very personal issue. Ruthia was in the beginning of her transition at that time. We were thinking about what gender means. We wanted to open a conversation with our colleagues and ask how other artists respond to this question. In order to take part in the exhibition, there was only one condition – to read Simone de Beauvoir’s book Second Sex. We asked artists to respond to it. While preparing for the exhibition, we organised a series of meetings where we familiarised ourselves with the history of feminist art. We were using the art space L.E.S. (Local Experimental Society). L.E.S. was initially a commercial co-working space in the centre of Almaty, then the owner decided to add an art space in order to make it more fancy. In 2012, Maria took the job as curator there. The owner gave her free hands in terms for content. At the time L.E.S. was the only contemporary art space in Almaty with weekly event programme and the art scene in the city gravitated around it.

However, Second Sex was not a feminist event. Most of the participants did not associate themselves with feminist ideas. This exhibition was more like a poll, a demonstration of what artists think about gender issues. Therefore, most of the art works in our exhibition were not feminist. There was a whole range of perspectives from the openly anti-feminist reactions to the most radical feminist positions.

Would you say that these exhibition changed the course of conversation about gender and feminism in Almaty?

It is hard for us to see the direct connection between what we did and how things developed. We cannot say that our exhibitions had a significant social impact. However, I remember the reaction of feminist researcher Svetlana Shakirova who attended the round table that we organised in the frame of the exhibition. We invited key figures from feminist NGOs and Shakirova was the founder of Gender Studies Institute in Almaty in the 1990s. She saw the exhibition and said "It took only 10 years for artists to start talking about gender issues." It would be fair enough to say that we initiated the talk about feminism in the context of contemporary art and culture.

After participating in our exhibition, some artists continued to develop these issues in their work. For example, Katya Nikonorova and Zoya Falkova, they are now feminist artists. Before our exhibition we did not know any feminist works by Zoya, but her contribution to our exhibition was a strong anti-patriarchal statement. Later she moved quickly towards making feminist art.

We continued working around these topics with another exhibition which also took place in 2013. It was titled Woman’s Business and it was dealing with women’s engagement in public life.

The feminist spectrum in Kazakhstan seems to have developed quite a lot since 2013. Would you bring a few examples of local initiatives?

Some NGO-s working with feminist and LGBT issues have existed in Kazakhstan since 1990s but they have not been seeking visibility in public sphere. This changed around 2015 when new organisations started appearing.

One of them is Feminita which has from the very beginning supported lesbian, bisexual and queer women. Feminita was founded in 2015, at the time even traditionally feminist organisations in Kazakhstan were not visible. One of the first that appeared was openly queer, in our context it was an unusual move. Feminita started with a large-scale research about the needs of lesbian, bisexual and queer women in different parts of Kazakhstan. They were travelling from one city to another and meeting women in local places. Therefore, this research also enabled community building and awareness raising.

Feminism has recently become quite popular and trendy, especially among young urban women with relatively good education. It is very much influenced by the Russian-speaking public pages and groups in Vkontakte and Facebook. That is the reason why there is also a presence of trans-exclusionary radical feminism in Kazakhstan. The feminist organisation KazFem is modelled upon radical feminism in Russia. Again, it was founded around 2015. KazFem is addressing issues around gender based violence and inequality, for example domestic violence and gender wage gap. They also organise demonstrations on the 8th of March – which is not easy – and smaller street actions.

There is also Kazakh version of the #MeToo movement to address sexual violence. In Russian-speaking contexts the commonly used hashtag is #NeMolchi, it means “Don’t Stay Quiet.”, and in Kazakhstan this movement is known as #NeMolchiKz. We have been collaborating with Alma-TQ, a transgender support group which was also established in 2015.

I am interested in the question of movement politics in post-Soviet contexts. It is not so easy to find examples of that. For example, in Estonia there is a growing liberal civil society which is organised in small-scale NGO-s that are dependent on government or EU funding. There are very few political initiatives that would maintain the autonomous structure of a movement, network or composition. These initiatives are usually short-lived – they come together in situations of urgency when quick reaction is needed, but once the campaign is over, they dissolve or in the best case transform into something new. How about Kazakhstan?

One example that comes to mind in response to your question is the so-called Kazakh Spring. In 2019 the president Nursultan Nazarbayev resigned after reigning more than 30 years. We never thought there would be a second president in Kazakhstan! This political transition opened new space for expressing dissent, triggering a wave of civil activities under the slogan Oyan, Qazaqstan, or Wake Up, Kazakhstan.

Oyan, Qazaqstan aims to become a movement. They try to function without hierarchy and leaders, and refuse to register officially. They are constantly emphasizing that the movement is not associated with any political party and does not belong to any political agenda. The aim is to make Kazakhstan more democratic. It is very much about the right to protest, to influence politics and to vote: one core demand is that presidents must be elected and changed, and elections must be real, not fake. The movement also addresses other civil rights, such as freedom of assembly and speech.

Banner “You can’t run away from the truth”, unfurled during Almaty Marathon in 2019. Photo by Tamina Ospanova

Oyan, Qazaqstan is also interesting because it has brought forth a circle of young artists who are actively contributing to the movement with slogans and visual images. This kind of collaboration is new. One famous example is the banner with the text “You can’t run away from the truth” which was unfurled during the annual Almaty Marathon, some days later another banner was hung on a traffic bridge, quoting a sentence from the constitution: “The only source of power is people.” Both protest actions led to the arrest of artists and activists who were held responsible for these banners, whereas the slogans “You can’t run away from the truth,” “I have a choice,” and “For fair elections” went viral on social media and began to circulate in pickets and demonstrations.

Prior to that, a very important moment for the political awakening in Almaty was the environmental movement that mobilised against the construction of a ski resort in the unique mountain landmark named Kok-Zhailau. It was the first movement that was massive. There were thousands of people who were ready to take the risk and protest in order to defend this natural landmark. Most of these people were not politically engaged, they were just trying to resist this absolutely uncontrollable power that can do whatever they want.

There is also Kazakh version of the #MeToo movement to address sexual violence. In Russian-speaking contexts the commonly used hashtag is #NeMolchi, it means “Don’t Stay Quiet.”, and in Kazakhstan this movement is known as #NeMolchiKz.

These are very powerful examples, but I am also thinking about more unspectacular modes of organising that I have found when doing research in post-Soviet region. I am often a bit hesitant how and when can one adequately apply the vocabulary of movement politics. Is a movement defined by the size, such as big street mobilisations? Or is it more about organising structures and modes of participation? Let’s take for example the recent development of feminist politics in Estonia. Feminism has a strong support base right now whereas many initiatives started from intimate reading groups or conversation circles gathering around the kitchen table. Most of such groups never reach the visibility that would “raise” them into the status of a movement. Yet as many feminist thinkers have pointed out, the kitchen table has been a key site of organising in many times and places.

How do you see this question from the perspective of Kazakhstan? In the situation where movements are not so easily constituted, are there perhaps alternative forms of political organising that are more common or relevant?

There have been some attempts to conceptualise the term тусовка. [1] In Russian language, tusovka is a circle of people who know each other quite well and often times meet here or there. It is connected to urban lifestyle – let’s say you live in the centre of Almaty, you go to cafes and parks, you visit friends and parties and generally hang out within the same network of people. For example, we are part of the tusovka of contemporary art in Almaty, and recently we got involved in techno music tusovka.

The techno scene is a good example of tusovka which is getting more active and more politically conscious in Almaty. You might have heard about Horoom Nights party series in Tbilisi, these parties are organised by LGBTQI activists who are creating safer spaces for queers within techno scene. We have something similar now in Almaty, a non-commercial techno club organised by two queer women. We made a 3-day exhibition in this club in 2018. The audience was a mix of art and techno publics, and we had some interesting political discussions with them. It was surprising how this space enabled talks that would usually happen only between friends. Like you said, previously the place for such talks was indeed mostly kitchens. But recently contemporary art and some underground nightclubs have become spaces where sharp political talks can happen.

Of course, there is also a lot of fear in Central Asia. The fear of doing something not acceptable is constantly in the back of your head. But this fear does not prevent you from being in disagreement. The dissent is still there, even if silent and invisible. When you talk to people, you hear that most of them are deeply dissatisfied.

Postcard by Krёlex zentre, 2015.

In the past months I have interviewed artists and activists from post-Soviet region about their political biographies. I have been hesitant how to work with those narratives without reproducing the stereotypes about authoritarian countries where civil society is oppressed with repressions and violence. Meanwhile, the tables have somewhat turned. Our conversation takes place in the midst of Covid-19 quarantine. We are located in different parts of European Union where our basic rights for movement, assembly and democratic participation have massively been restricted. I think this is a good moment to ask what we can learn from the experiences of people who are active in contexts where the restrictions on civil liberties were already harsh before. Last week I was collecting visual images linked to political organising in Belarus. I found plenty of images with one person holding a sign in public space, because organising collective protests is more difficult. However, collective protests are currently not permitted even in those countries that are considered liberal and democratic. Can you think of any tactics from Kazakhstan that might be useful today for example in Vienna where you now live?

Once we made a street installation which is similar to what you just described. It was after the massacre against the striking workers of the oil field in Zhanaozen. In December 2011 the workers were shot and killed and the whole protest was very brutally oppressed. Everyone was in shock. We made four human size snow figures in the park. It was in the last days of winter, two and a half months after the violent events, there was still snow. The snow figures were standing in a group, holding signs: "This is a picket. This is a real picket. No kidding. We are scared." The message was clear – it is not a game, we are really protesting here. We are really scared but nevertheless. We stayed in the park for a while, observing people who passed and made photos. Later on the images spread in social media.

Maria Vilkovisky, Ruthia Jenrbekova, Till Ulen, Snow Picket. Intervention in public space, 2012. Photo by authors

One story of autonomist organising in Estonia starts with the snow figure. The snow figure protesting against climate change was the first gesture that was collectively done in 2006. There are such odd chains of association how some forms of protest travel from one context to another. But in the situation of weak movements, like Estonia or Kazakhstan, a snow figure might have the strength of a demonstration.

We personally believe in weak power. Krёlex zentre is based on the idea that the powerless and non-existent have their own power.

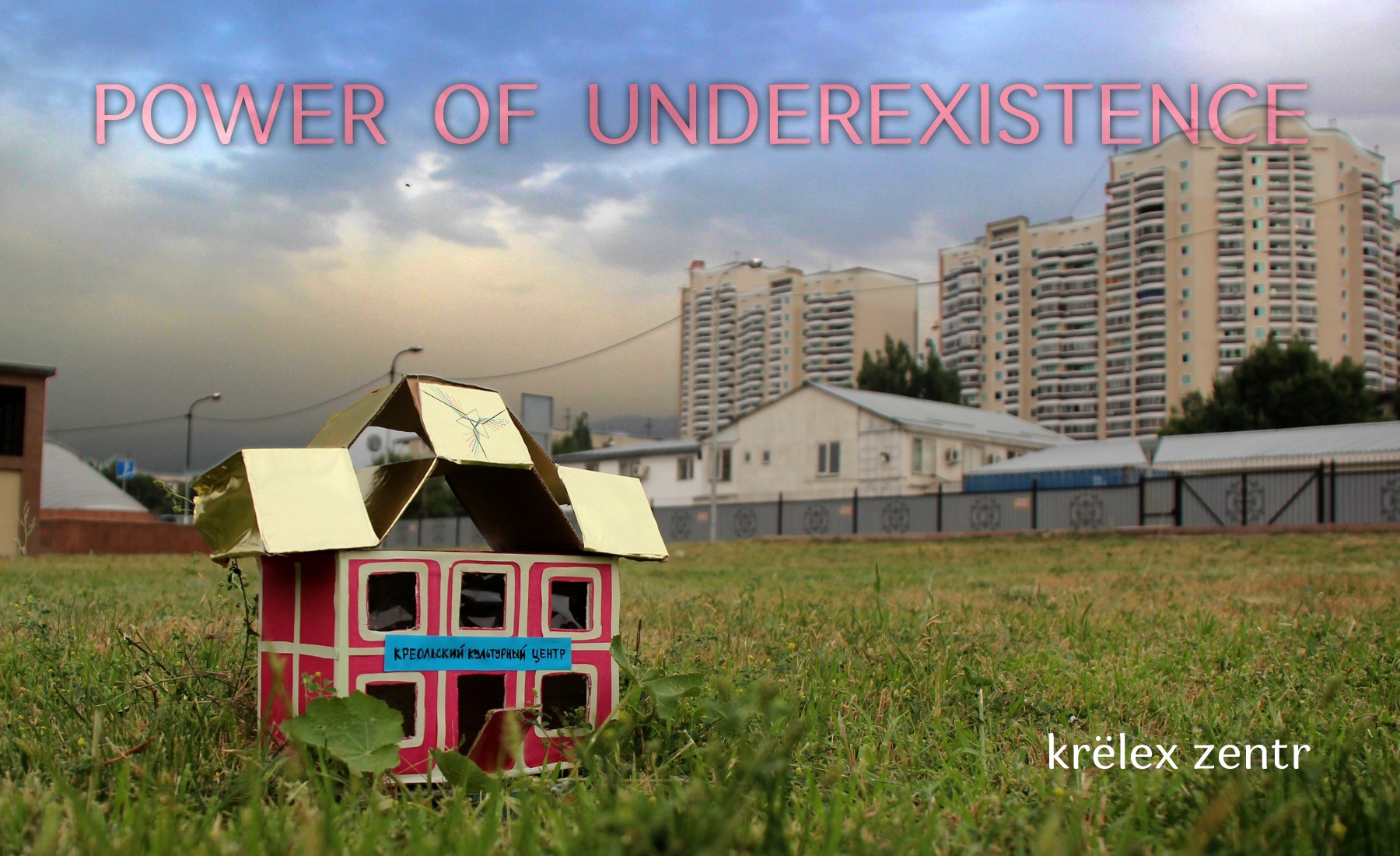

We personally believe in weak power. Krёlex zentre is based on the idea that the powerless and non-existent have their own power. We have a postcard where our cultural centre is made out of a shoe box. It is something that does not exist in reality, but on the image it is integrated into landscape. That is how we understand the role of artists. As artists we are dealing with imaginary things that don’t exist. Nevertheless these non-existent things can produce certain effects. Our role is to emancipate the imagination which is oppressed by solid reality. Imagination cannot forcibly break through the limitations of the stronger solid reality, but it can transcend and emancipate from its constraints.

[1] See for example: Viktor Misiano, The Cultural Contradictions of the Tusovka, Moscow Art Magazine 1/2005

The interview was made with the support of the Fellowship Program for Art and Theory at Künstlerhaus Büchsenhausen.