Bodily memory is a long-term memory

An interview with Israeli artist Yaara Zach

Yaara Zach (1984) is an Israeli artist living and working in Tel Aviv. Zach is best known for her body scale objects and sculpture-based installations involving ready-mades and industrial materials that are related to the body but at the same time are new and unused. Zach’s exhibition Black Friday, which has a rather extraordinary and significant history of creation, is currently on display at the Givon Art Gallery (through August 1) in Tel Aviv. The opening of the exhibition was planned to take place in the days when, suddenly, the COVID-19 crisis had intervened quite radically and unexpectedly. As the pandemic emerged, Zach’s works, which were produced between 2016 and 2020, gained a whole new sense of agency and the feeling of having an almost telepathic context.

In an essay on the exhibition titled A Prototype for Survival, writer and curator Naomi Lev writes: ‘Yaara Zach uses industrial materials to create an imaginary natural world. Is it imaginary, though? Her current works are based on nature and natural evolution, and are inspired by animals’ means of survival as well as our own survival instincts. The works in this show were made prior to the pandemic that has conquered our globe, yet they represent elements from the past as well as from the present. They bring forth moments of birth, death, and rebirth while creating a groundbreaking experience that proposes a mirror to a multilayered existential reality.’

Yaara Zach holds a BFA and an MFA from the Bezalel Academy of Arts and Design. Her works have been included in various solo and group exhibitions in Israeli and international exhibition venues including The Israel Museum, Jerusalem; Tel Aviv Museum of Art; the Moscow International Biennale for Young Art; the Berardo Collection Museum, Lisbon; the Bezalel Academy Gallery, Tel Aviv; RawArt Gallery, Tel Aviv; Artport, Tel Aviv; Janco Dada Museum, Ein Hod; Ashdod Museum of Art; Haifa Museum of Art; and Petach Tikva Museum of Art.

Arterritory sat down for the following interview with Yaara Zach.

The works in this exhibition were made before the pandemic. In some way, you appear to have foreseen its coming. How did the idea for this exhibition come about?

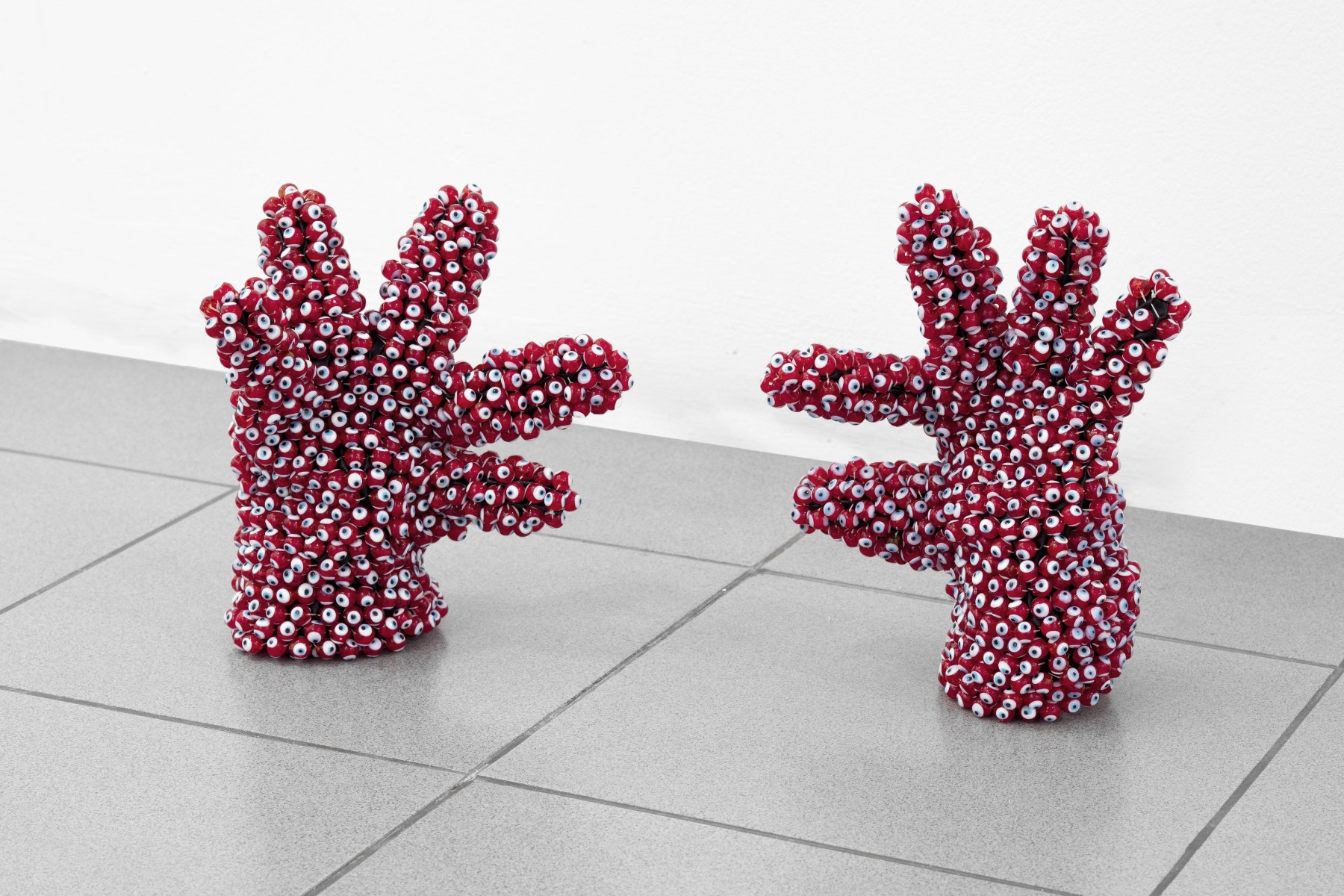

The exhibition continues my involvement in the past decade with ‘surviving objects’, which draw their logic from mechanisms developed by organisms for the purpose of survival. Colour, shape, structure – all of these play a role. The exhibition evolved from the work Evil Eye, an object made of a women’s suit covered in evil eye beads (traditionally used for protection from the evil eye, a curse believed to be cast by a malevolent glare). The beads were stitched into the suit on both the inside and outside, in a sort of cellular multiplication of an overflowing body. Over time, a coating formed around it that fossilised it. This work, which originated from thinking about the object’s magical power, collapsed under its own weight. I started it in 2016, and it lay in my studio for a few years and permeated the works that were to follow. The logic of the exhibition was based on infection. Parts started to encroach upon one work from another – to infect each other.

Yaara Zach. Tent, 2019-2020, fur coats, sportswear, tent, latex, stainless steel, paint, steel cable. Photo: Tal Nisim

One of the things that came up very forcefully when people started talking about Corona was the fear of contact – not just with other living bodies but also with still objects. The objects became potential carriers of a living body. This is something I engage with – the moment that the body and the object are united.

Yaara Zach. Black Friday, exhibition view at Givon Art Gallery, Tel Aviv. Photo: Tal Nisim

Have you ever been confronted with the reality of survival? What does surviving mean to you? Quite often we use it just as an abstract word – as a part of storytelling – since we are used to believing that whatever happens, one way or another, things will turn out alright.

My works touch upon my biography, but indirectly. I deal with situations the body enters as a response to extreme conditions. The body becomes something almost completely other, submerged in its own survivalist existence. Some works in the exhibition refer to bodily situations of invasion, penetration, freezing, disappearance, and collapse, and also to the enormous vitality that exists in dangerous situations. Many of the works are in a condition of response, but it’s not always possible to know what they are responding to. They have no single narrative, but several narratives fitted upon each other. At the same time, they always return to my bodily experiences.

Yaara Zach. Black Friday, exhibition view at Givon Art Gallery, Tel Aviv. Photo: Tal Nisim

Some of them are taken from the Israeli street and the experience of wandering and living here. The context in which I grew up as an Israeli, soaked in the atmosphere of constant survival. Whether during times when missiles are falling, or when there are terrorist attacks, and even during times that are apparently quiet, the survivalist, militarist experience is an inseparable part of existence here. Precisely because it’s usually suppressed, it permeates the most everyday places and moments, and finds expression in meeting people, in street life, in the language, and in body language. This reality is internalised in them. The experience of the lack of boundaries between territories, between living bodies, and between spaces activates me. This exists in works like Tent, that was built of dozens of synthetic fur coats that were disassembled and reconnected, or the works Cocoons, Hungry Eyes, and Pale Horse, some of which are made of latex and some of silicone, materials of insulation and separation. The sculpting action is of penetration. Pipes penetrate the structure and create a flexible alien skeleton. Sculpture often has an issue of power relations.

Yaara Zach. Black Friday, exhibition view at Givon Art Gallery, Tel Aviv. Photo: Tal Nisim

What did you understand about yourself, about your daily habits and relationships with the world/things around you, with non-human animals, while working on this project?

Already at the beginning of preparing this project, the works touched upon moments when human and animal bodies connect, when humans are stripped of all their shells and remain bodies, organisms activated by places of survival. At some point during the process, I got pregnant and the work continued during pregnancy and after I gave birth, which really intensified these places in the works.

The experience of pregnancy was very powerful. Often, the bodily experience is almost transparent. When all physicality changes, bodily needs and abilities rule – our awareness of our physicality is almost unceasing. During the final hours before childbirth, I couldn’t tolerate light at any level and crawled into a dark place. This was not a choice but a necessity. I had to do this. I think something in my perception of myself as an animal first and foremost was strengthened in these moments and permeated my later works.

Yaara Zach. Tent, 2019-2020, fur coats, sportswear, tent, latex, stainless steel, paint, steel cable. Photo: Tal Nisim

There was a moment when the works were almost finished, but the exhibition had not yet opened and I was waiting for the lockdown to end, when something almost completely opposite happened that fascinated me: the city of my birth, Haifa, was flooded with wild boars, and jackals were wandering around Tel Aviv. The urban space returned to function as nature, and animals returned to rule it for a moment, instead of us.

Yaara Zach. Pale Horse 2018-2020, silicone, pipes, thread. Photo: Tal Nisim

Which are the most animalistic characteristics in human animals?

As I see it, there is no real distinction between humans and animals. I deal with places where the human body is revealed in its animalistic form. I referred to this in an exhibition called Black Friday. Many of the items I bought for these works were purchased all at once, during a Black Friday event, and immediately cut up and turned into new raw materials. This was also an expression of the sensations that arose in me during this event and what I absorbed from the surroundings. This was a sort of ‘hunting in the heart of the city’. Naomi Lev referred to this well in the exhibition text (link to exhibition text).

Yaara Zach. Red Hands, 2016-17, gloves, evil eye beads, thread. Photo: Tal Nisim

Yaara Zach. Evil Eye 2016-2020, beads, suit, thread. Photo: Tal Nisim

It is well known that the human species has a short-term memory. We can see it already. Everyone was hoping for a change, but as soon as the situation gets better in many places, these ideas of change move further away. How fast we will forget about this pandemic? And are we learning something from this situation, or will we just quickly adapt to it?

We have to distinguish between forgetting and the internal or external mechanisms, often aggressive, of enforcing forgetting. We can easily indicate points in time that left their mark and sowed the seed for chains of events and developments as a result of an event that caused a collective trauma. It is actually the body that is less obedient in this respect, and therefore, in my eyes, it is more interesting. Bodily memory is a long-term memory and can awaken automatically given the right trigger. When the Corona crisis started, I thought about it largely through my son, who was one year old at the time. I thought about what sort of world he would grow up in, and what would be possible in terms of intimacy and touch. It’s interesting to see how physicality and intimacy are translated into danger, with the boundaries of the body and of space being threatened or unclear. This is an aspect I dealt with in my previous project Unreasonable Doubt, which was shown as a solo exhibition in the Petach Tikva Museum and at the Moscow International Biennale for Young Art in 2018 (link to Unreasonable Doubt).

Yaara Zach. The Couple (I,II), 2019, jacket, thread, plastic (on the floor). Photo: Tal Nisim

Yaara Zach. The Couple (I,II), 2019, jacket, thread, plastic (on the floor). Photo: Tal Nisim

If we look at this pandemic as an opportunity to re-valuate/question our attitude towards things, existence models, and ideas about how we are going to live in the future, what are the main lessons the art world should learn from this crisis?

I was fortunate that the exhibition opened exactly during the break between the first lockdown and what seems, at present, to be turning into a second lockdown here in Israel, and not for practical or medical reasons. One of the things that shocked me during the first lockdown was the loss of public space. In a city like Tel Aviv, where private spaces are small and all of life takes place in the public space, this was a very strong experience that broke the illusion that this space is a safe thing; it reinforced the awareness that it could be taken away at any moment for various reasons. For me, this awakened the desire to create works for the public space. This is a new project that I am working on.

Yaara Zach. Left Hand, 2016-17, glove, evil eye besds, thread. Photo: Tal Nisim

Yaara Zach. Untitled, 2019-2020, industrial embroidery on silicone, metal, steel cable. Photo: Tal Nisim