Woodstock, raves and the image recycler

An interview with British artist Seana Gavin

Seana Gavin is a British artist whose collages pick up on the vibrations of an era with neurosurgical precision – both the easily visible vibrations that confront us on a daily basis and those that quiver on the metaphysical plane – reminding us once again that not being able to see something does not mean it does not exist. Her collages are like Alice in Wonderland’s interplanetary adventures, in which the past, present and future coexist in psychedelic symbiosis and mushrooms embody architectural forms reminiscent of 1960s and 70s sci-fi amidst references to 1990s rave culture, tunnels of reality between dreaming and wakefulness, ancient civilisations and a 21st -century rocket shooting off into space.

Gavin spent part of her childhood in Woodstock and part of her youth travelling around Europe in the 1990s with the Spiral Tribe sound system collective and participating in illegal raves. She was only fifteen years old when she joined the underground rave scene in 1993, staying with it for a whole decade. Some of Gavin’s photos and diary entries from that time were released this summer in the photobook Spiralled, published by IDEA Books. With 192 pages, the book is one of the rare truly personal documentations of that movement.

Gavin’s collages, for their part, are on show along with work by forty other artists in the Mushrooms: The Art, Design and Future of Fungi exhibition at Somerset House in London until September 13.

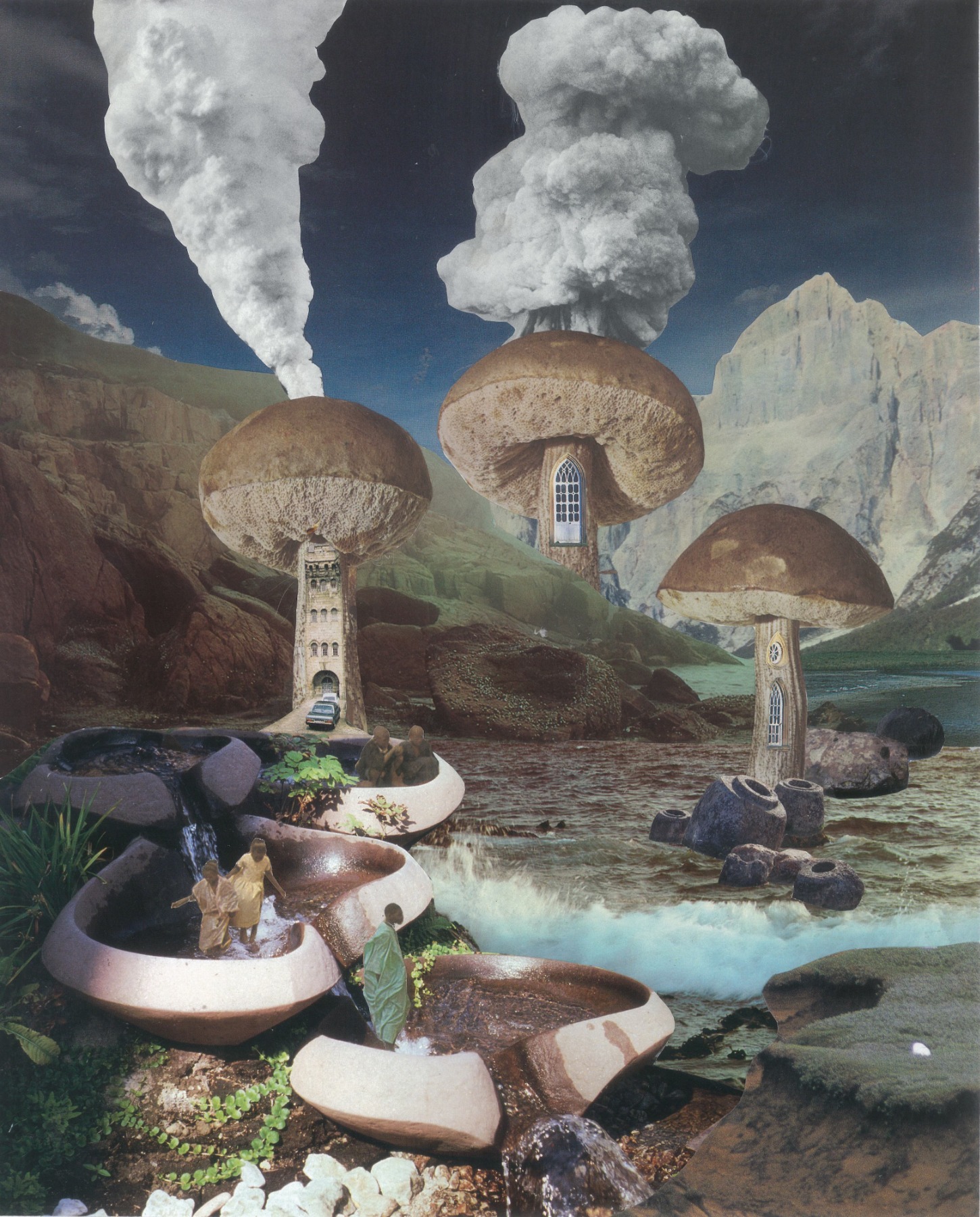

Seana Gavin. Untitled Mushroom Chimneys, 2017.

Our conversation about art, mushrooms, raves, Woodstock and the possibility of a third Summer of Love took place on Zoom. Gavin joined me from a small town in Oxfordshire, to where she had moved already a couple of months before the Covid-19 pandemic began.

In reference to Mushrooms: The Art, Design and Future of Fungi, the current exhibition at Somerset House, which also includes your own work, I’d like to start our conversation with mushrooms. As we know, humans share nearly 50 percent of their DNA with fungi, and we even contract many of the same viruses as fungi. Mushrooms existed before us, so in some way they’re our elders and we are their descendants. We diverged from them 650 million years ago. But at the same time, people are afraid of mushrooms, afraid of their “mushroom identity”. Why is that?

Do you mean that people can be repulsed by fungi? I guess they think of them as mould and decay and not clean. But yes, that’s interesting. I knew that mushrooms were more closely related to humans than plants, but I didn’t know how connected we were to mushrooms until this show at Somerset House.

I’ve always been fascinated by fungi from an artist’s perspective. They’ve always fascinated me, both physically and aesthetically, as a form. There are millions of species, and their variety is incredible – their shapes, their colours, their sizes. So I’ve never been repulsed by fungi myself. Mushrooms have regularly appeared in my collage work, ever since I began making them. It wasn’t such a conscious thing for me – like I said, I was just interested in them physically.

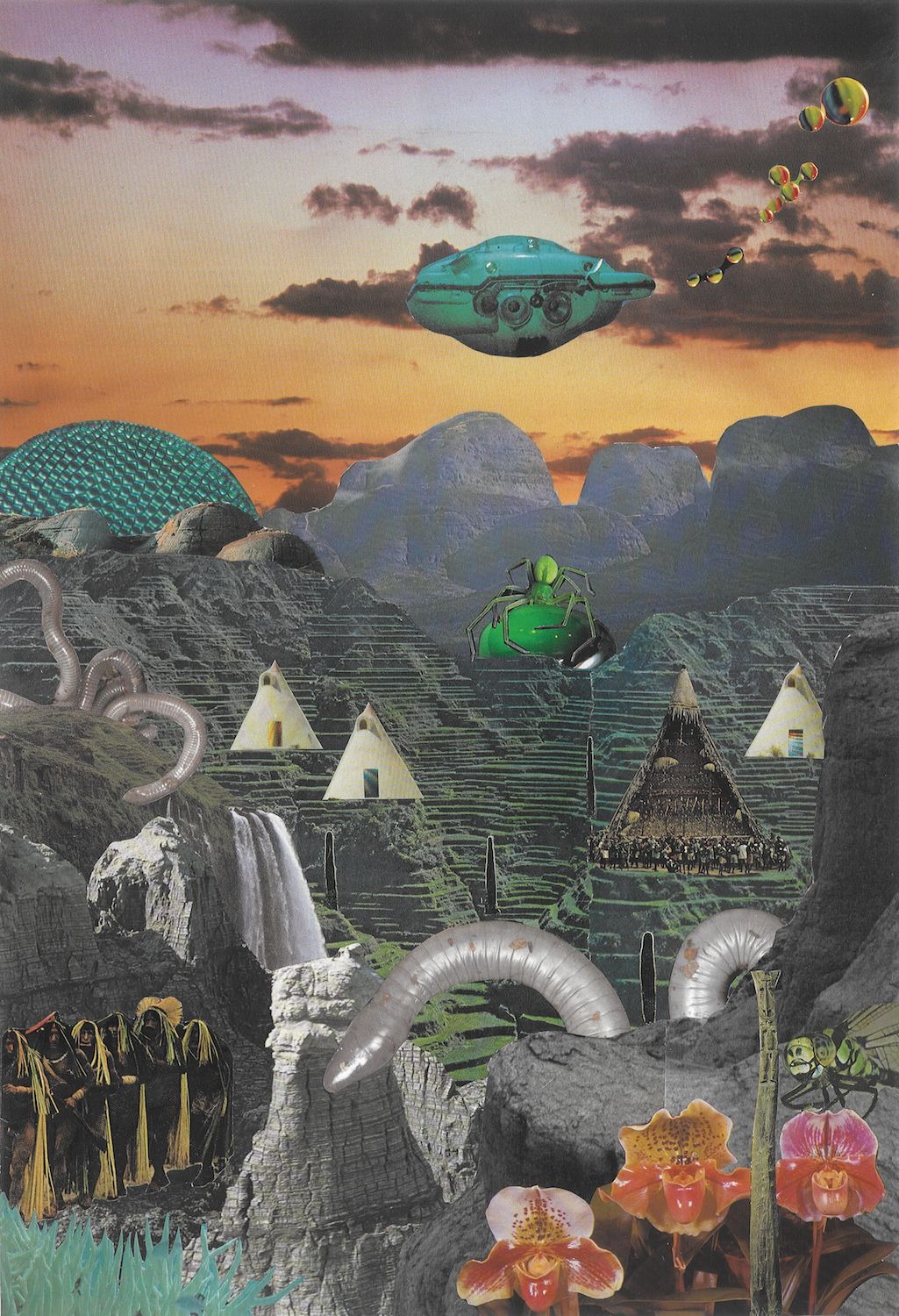

Seana Gavin. Glactic mushroom highway, 2019.

I guess my work is quite surreal, and the landscapes I make are often inspired by science fiction. I think that relates to my childhood – fairy tales, Alice in Wonderland, science fiction and so on. I’ve always liked to play around with the mushroom as a form, changing the scale of them, making them really oversized, which also changes the human relationship to them. I also like to play around with mushrooms architecturally. I turn them into buildings and imaginary architectural structures.

I’ve always liked to play around with the mushroom as a form, changing the scale of them, making them really oversized, which also changes the human relationship to them.

I was so happy to be included in the exhibition at Somerset House, but it wasn’t until the show opened that I realised the general public’s huge fascination with mushrooms. I mean, they’re so popular, people absolutely love them. And the exhibition is so popular that we’re getting thousands of visitors a day. It’s such a broad spectrum of people, too. Lots of people are interested in mushrooms from the edible perspective. It’s a big thing now with the health food movement, because mushrooms contain so many nutrients. For example, there’s an alternative mushroom coffee powder and things like that. And then, of course, there’s the psychedelic side of mushrooms as well as mushrooms as a sustainable, biodegradable material in the world of design. In fact, the future of fungi as a construction material is something I didn’t know about before this exhibition. And also that fungi can create a kind of underground network through which they communicate with each other. In any case, it’s a fascinating show, and there’s a series of talks and workshops coinciding with the exhibition as well.

Seana Gavin. Times gone by, 2014.

You mean networks like a kind of fungi internet?

Yes, something like fungi intelligence. Scientists have already done tests with them and explored how fungi react to things physically. It’s almost like they’re actually thinking and there’s a thought process going on in there with how they form.

Renowned mycologist Paul Stamets also speaks a lot about the importance of mushrooms in the architecture of our existence. He has found that mushrooms could help save the world’s ailing bee colonies, because there’s a fungus that provides powerful medicine in fighting honey bee viruses. Do you agree that plants and also mushrooms have a kind of consciousness?

I think they do. I remember a book that my mum had on the shelf when I was a child. It’s called The Secret Life of Plants and is all about how plants communicate, including with each other. My mother has always said that she speaks with her house plants. And I believe plants can probably pick up on energy and vibrations. So if you play music in your house, it probably helps your plants to grow. I think they definitely have some kind of consciousness. In a way, I think nature and the botanical world connect us to the universal consciousness. I’m not religious, but I feel that nature is kind of like God, in a way. Like our higher self. That’s what I see in nature. I feel like there’s a kind of consciousness flowing through everything.

In a way, I think nature and the botanical world connect us to the universal consciousness.

You already mentioned the psychedelic side of mushrooms. Interest in this aspect has noticeably increased in recent years, and currently we’re experiencing something like a psilocybin mushroom explosion. What’s your opinion on the current psychedelic renaissance?

I feel that interests and trends tend to happen in cycles, and it seems like there are a lot of parallels between the early 1990s and the things going on now. You know, it kind of skips a generation. Like, first it was the free love era of the 60s, when that whole new world opened up. Then there was the punk era in the 70s, and in the 90s a variety of subcultures. Then it seemed to have gone to sleep for a while, people conformed, including the younger generations, who were generally more interested in materialism, becoming famous and how many Instagram followers they had. But now it feels like more people are looking back to the 90s again and seeking an alternative lifestyle.

I feel that interests and trends tend to happen in cycles, and it seems like there are a lot of parallels between the early 1990s and the things going on now.

It makes sense that the increasing interest in mushrooms as a psychedelic substance is a comeback in that cycle. I personally haven’t been dabbling in them myself, because, well, I did experiment when I was much younger, but I didn’t have a very good time with it, so I wouldn’t go there again. But I do find it really interesting how mushrooms seem to be so popular again at the moment. People are really into microdosing in various forms, like mushroom sprays, etc. I’ve been at weddings and other events where these mushrooms have come out. There’s definitely a bit of a revival going on.

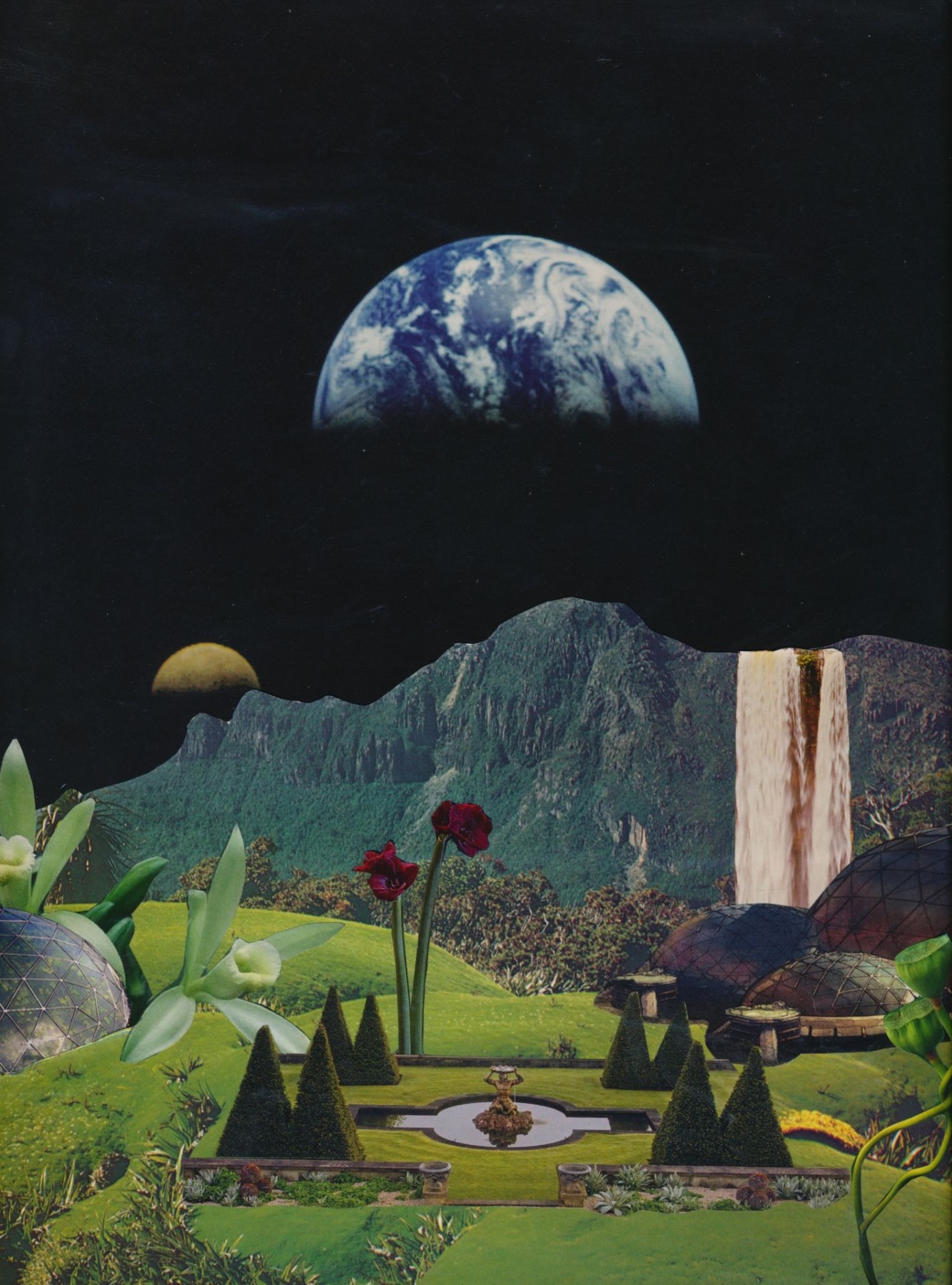

Seana Gavin. Evergreen Metropolis, 2018.

You stopped experimenting with these substances because of bad trips. Is there such a thing as a bad trip if you look back on it from a distance? What have those bad trips taught you, if anything?

Well, I try not to have any regrets. I experimented more with acid than with natural mushrooms, and maybe if I had started with more of the natural stuff, then I would have had a better experience. I think with acid it’s more chemical and toxic. I guess I was just too young to handle it. I never really had a good time and always had bad trips. But it probably opened up my imagination. I mean, when people look at my work, they say they can see clear psychedelic references, which aren’t necessarily intentional, but the ideas that go into my work or the visions that come up in it probably stem from those experiences.

Some of my pieces depict utopian paradises, landscapes and other worlds. But other times they have a darker edge, which may stem from my history with bad trips. But I also believe that you can’t have good without bad. And also in our daily lives, we have to have this balance – we can’t have one without the other. I feel like in my work I’ve always explored both sides of the spectrum.

Yes, psychedelic references are one of the first to come to mind when looking at your work. But as far as I know, you also practise lucid dreaming. When did you start that, and what have you understood about life via lucid dreaming?

From a very young age, I’ve always been interested in my dreams. As a small child, I had lucid dreams without even realising it – I didn’t really know what they were. When I got older, I learned that was the name for what was happening to me. Basically, I would wake up inside a dream. I was aware that I was dreaming, and I could control what was happening in the dream. But now that I’ve become more interested in lucid dreaming, I realise that there are people who work really hard to be able to do just that, but for me it was occurring naturally. Because I’m a distinctly visual person; when I wake up, I often have the feeling that what I experienced in my dreams was real. Sometimes it seems that the dream world is simply a parallel world to our daily life. Like sometimes you wake up and you think “was that reality?”

In my work I’m more interested in the different states of consciousness rather than reality itself. And in the places where the rules of reality don’t really exist. That also makes my work more fun to create, because I can add in really surreal elements.

In my work I’m more interested in the different states of consciousness rather than reality itself.

Can you say that dreams are in some way objective? That they’re real?

Well, I guess they are real for the short time that you’re experiencing them. Because if you’re experiencing it, then it’s real in some way. It’s hard to 100 percent know what is reality, but sometimes you really don’t want your dreams to be real.

You’re interested in the concept of time as well. What fascinates you most about the different ideas of time? For example, for the Hopi Indians, time is a continuum, without a defined past, present or future. They don’t even have a word in their language for “time”. What have you discovered anew in the notion of time while looking at ancient civilisations?

Yes, time has become a bit of a recurring theme in my work after I had my solo exhibition in London in 2014, which was called End Times. I was creating these visions by combining ancient civilisations with ideas about future civilisations, which somehow coexisted in the present. I was mixing up all kinds of different references from the symbolism of the Egyptians, the Aztecs, the ancient Greeks and so on. They worshipped many gods. For example, in Egypt, the sun god Ra was the ruler of time.

There are a lot of theories about measuring time. And all of these cultures measured time before we had clocks. One of the earliest devices to tell time was, of course, the sundial – a sun-powered clock that indicates the time of day by the position of the shadow of some object exposed to the sun’s rays. I started looking into the sundial as a subject when I had that exhibition, and I realised that there were so many different theories about time in different religions. Like in Hindu philosophy, they believe that time is an illusion.

In my work, I’m often creating science fiction-like landscapes. I’ve always enjoyed watching retro sci-fi films, which often feature ruins or ancient civilisations that have withstood the test of time. The evidence of those civilisations might just live on for thousands of years.

This imagery often inspires my creations. I don’t apply these things intentionally, but I guess they kind of seep into my mind and into my work. When I’m creating a new piece, I don’t really overthink what I’m doing. It’s a very intuitive, organic process. When I’m working, I feel like I’m almost in a meditative state. It’s all unfolding, something is taking over. I try not to analyse or overthink.

When I’m working, I feel like I’m almost in a meditative state. It’s all unfolding, something is taking over.

We often use the expression “here and now”. Like this conversation is also happening “here and now”. Is it possible to be, to feel, to define “here and now”?

It sometimes feels like everything’s kind of existing at the same time. If you start thinking about the past or what might happen in the future, it all becomes quite abstract. I think we often go about our lives on autopilot. We do a lot of things in our daily lives very mechanically. But to be fully present, you sometimes need to stop what you’re doing, which relates to mindfulness or meditation, in which your brain isn’t thinking, you’re just still. And maybe those are the only moments when you can be really, truly aware of the present.

It’s good to stop whatever the task is that you’re doing, even if you’re walking in nature, like la, la, la...just looking around. You actually have to stop and, wait a second, look where you are, look at your surroundings and be really conscious of your existence, and be aware of how amazing it is.

Do you believe in the multiverse theory, and have you ever had a multiverse experience? Judging from your work, one might assume that you have.

With the work I make, sometimes I feel like I’m connecting to parallel universes. I often make these hybrid creatures, mixing different humans with animals. Sometimes I think that if it’s something I can imagine in my mind, it’s also something that could actually exist in a parallel world. When I enter the state I’m in when I create a work of art, it could be that I tune into parallel universes or different worlds. I’ve always been interested in the idea of life on other planets and what exists beyond us on Earth. I think it’s likely that there are other life forms beyond our planet. At least, it’s more likely that they do exist than that they don’t. Why should we be the only living creatures in the whole, entire, endless universe?

When I enter the state I’m in when I create a work of art, it could be that I tune into parallel universes or different worlds.

That’s what many people say about their psychedelic experiences, that they meet entities from different parts of the universe.

Yes, I remember reading Robert Anton Wilson’s book Cosmic Trigger I: The Final Secret of the Illuminati when I was about fourteen years old. It was more related to people taking mescaline, but there was a whole chapter about meeting this figure called Mescalito – a little green man that they communicated with. Meeting this little green man was something recurring, something that lots of people were experiencing when they took mescaline.

Seana Gavin. Somewhere other than here, 2014.

You spent your childhood in Woodstock. How do you remember those days, and have you ever been back there? If yes, does the place still have the same energy as before, or has that been lost?

I spent my childhood in Woodstock from when I was about four until about nine, so it was quite an important chunk of my childhood. I do remember it really well, so vividly. I definitely think the place left its mark on me. There were still lots of references to the 1969 festival and psychedelia, and also quite a few people who were left over from that time. There were kids at my school who were called Star and Rainbow. Woodstock was built on an Indian burial ground, and I always felt it was a bit like Twin Peaks. There were a lot of strange sightings of UFOs and so on. I myself had a lot of strange childhood experiences there, seeing lots of unusual, unexplainable things.

Woodstock was built on an Indian burial ground, and I always felt it was a bit like Twin Peaks. There were a lot of strange sightings of UFOs and so on.

The town was also a magnet for creative people. There was a history of musicians, artists, poets and writers ending up there. I really missed Woodstock when I moved to London at the age of nine, where I spent the rest of my childhood and teenage years. It was quite a big change. I longed to go back to Woodstock, but I didn’t get back there for at least ten or fifteen years. A really long time. And when I finally did, I really felt it wasn’t the same place to me anymore.

It’s weird, because it was basically like travelling back to my childhood, and at that point in my life it felt kind of sad, and there was a strange empty feeling there. I mean, there were still things there that I remembered as a child. Like the Tibetan monastery that was still there. I remember we visited it with my mum and my twin sister when we were five. We sat in a room full of about fifty Buddhist monks, all in meditation, and my sister and I just sat there quietly and instinctively meditated along with them. I’ll always remember that – it just felt like the natural thing to do. So yes, the monastery is still there, and my father still knows people who live in Woodstock. We visited a few of them, but overall it just felt a bit empty and strange.

Seana Gavin. Solar eclipse free Festival, Hungary, 1999.

But Woodstock definitely has a history of counterculture, DIY culture. Lots of people building their own houses, etc. I still have this book from when I was a child – it’s called Woodstock Handmade Houses. You know, people built these crazy mushroom-shaped houses. And maybe that’s where the inspiration for my mushroom architecture stems from!

So, in essence, only a shell of Woodstock’s former energy remains there today?

I went back there a second time, about four years ago or so. It feels very much like a weekend-focused place now, but I was there mid-week and it just seemed empty. But it’s a very beautiful landscape, surrounded by the Catskill Mountains. I think that’s also where my love for nature began, even though I became quite urbanised after that as I grew up in London. But I think part of me is always connected to nature, and that goes back to my time in Woodstock.

You studied drawing at Camberwell College of Art, but you eventually turned to collage instead. How did you come to work with collage?

I did a drawing degree at Camberwell, but I didn’t have the best experience at art school. There was too much overthinking. The course became very focused on the conceptual. But for me, using that side of the brain blocked my natural creative flow. I actually didn’t make any artwork for several years after I left art school. I had to wipe a clean state and just start afresh.

It was my sister, Francesca Gavin, who’s a curator, who suggested collage to me. She was like, “I think you should try this, I think this is something that you could connect to.” I remember the first collage I did; it felt like such an immediate thing. I just started playing around with pieces on the page, and it just fell into place, and I was like, “Oh wow, I don’t feel blocked anymore!” I no longer had the feeling that I used to get with drawing or painting, when I was faced with the daunting feeling of an empty canvas in front of me. But with collage I felt free again, and I discovered the joy of creating again and just having fun.

In the beginning – I guess this was about ten years ago – I never even imagined that anyone was ever going to look at my work. I didn’t make it for an audience. It was just a creative outlet. And then there was a quiet winter, and I decided to do a whole heaven- and hell series. Which was quite Hieronymus Bosch inspired – very full of symbolic images. I showed a couple of those works to someone, and that eventually led to a solo exhibition.

Seana Gavin. Rave in a quarry, near Brighton, 1999.

That was the first time I showed my work to the public. There was a great response, and then it just flowed very naturally after that. But I really made a point in the beginning of not looking at any other collage artists. For the first year or so, I didn’t want to feel like I was being influenced by any other work I saw. I wanted to feel like I was developing my own style and my own approach to it. But of course, after a couple of years I began looking at what else was out there.

I love Max Ernst’s collage series, for example. But he had a very different approach. His work is all mainly black and white, using black-and-white illustrations from different books that he combined together. Now, in the contemporary world, we have an almost endless choice of material to work with. We are overloaded with books and magazines. We have much more choice with how to approach collage.

In fact, now it seems to be becoming quite a popular medium, with many thousands of collage artists in the world. But when I began with it, I didn’t really feel like it was on people’s radar.

Why is it becoming so popular now? What’s your explanation for it?

I don’t know, I guess it just became one of those trends moving through the art world. Or else maybe it’s just a natural way for people to respond to the overload of imagery around us.

I feel I’m kind of like an image recycler. You know, I find these old images and turn them into something new. I don’t know, maybe it’s people’s sense of awareness as well, because as a medium, collage is quite ecological. Back then, when I was thinking about how to resume working, I was faced with this dilemma – how many young artists can afford oil paints and all the other necessary materials? But collage is free. You can find free newspapers and magazines everywhere. You don’t really need that much to get started and actually turn it into art. There aren’t many tools to buy, except for glue, scissors and a good cutting mat. It’s quite easy and accessible.

I feel I’m kind of like an image recycler. You know, I find these old images and turn them into something new.

What kind of materials do you use? Newspapers, magazines, books? Do you search for them, or do they find you?

I use mainly old books and magazines. I do have a huge collection of images in my studio that I’ve amassed over the past decade. Every time I come across a second-hand book shop or charity shop, I have to go in. I love the older, more vintage photographic material from the 1960s, 70s and 80s. The colours are more exaggerated and have a more grainy feel to them, sometimes more resembling paintings. I’m very attracted to that kind of material, old National Geographic magazines as well. Sometimes I also find books or magazines with very hyperreal, clean, contemporary imagery. I often like combining the two, because it gives quite an interesting contrast. It’s like mixing time: the past, present and future.

Seana Gavin. Dawn of a new world, 2020.

I have an ever-growing library of material that I use. I try to organise it and keep images in separate folders. When I look through books or magazines, I sometimes come across images that I know will be useful at some point, and then I try to file them in folders. For example, I have a folder for body parts, and it helps with the process when I’m trying to find specific things. Every once in a while I have to find things on the internet and get them printed, especially if it’s for a commission. But I try to do that as rarely as possible, because the quality of a printed image is never the same as when you’re taking it directly from the source.

A recent interview with Teeth Magazine stated that, in our uncertain times, your work and creative vision “provide attractive escapism”. Is that your goal? Or, quite the opposite, through your work do you try to open portals to different coexisting realities?

I guess in some ways I want viewers to feel like they’re really physically entering a space. That’s where my art background comes in. When I’m making my pieces, I’m very aware of having this sense of perspective. In that sense, my work might give a sense of escapism to the viewer, as if they’re actually physically travelling in their mind, travelling to somewhere else.

You travelled through Europe in the 1990s and early 2000s with the music, arts and free party sound system collective known as Spiral Tribe. This summer saw the launch of Spiralled, a photobook that brings together photographs you took during that period while participating in and documenting the illegal rave scene. Why did you think this was the right time to open your archive to the public and release the book?

It all began last summer, when I had a solo exhibition, Spiral Baby, at galeriepcp in Paris. It showed an archive of photos that I’d taken between 1993 and 2003, when I spent periods of time travelling with sound systems, including Spiral Tribe, across Europe. I had emotionally buried that period of my life until that exhibition.

Meanwhile, in the past few years there’s been a huge interest in the rave movement and subcultures of the 1990s. That’s when I started thinking that it was time to share my archive and not just keep it to myself. Especially because there weren’t many people documenting it at the time. Those were the days before smart phones, and not many people had cameras at the parties and events.

So I had that show, Spiral Baby, and it led to me being exhibited at the Saatchi Gallery last summer, in the group show Sweet Harmony: Rave | Today. The show coincided with the thirty-year anniversary of the so-called Second Summer of Love, which was in 1989, when the acid house movement started to develop in the UK.

I had wanted to compile my photos in a book already before both of those shows, but in the end, having exhibitions helps to get a book printed. It was quite a fast turnaround. I got the publisher in January, and we were originally going to launch the book in May. Then Covid-19 came along and delayed everything. But in the end, I think it worked in our favour, because by the time we did release the book, which was the end of June, it was like perfect timing for the release of this book in a summer when no music events or festivals are happening. Gatherings of more than six people are not allowed, at least not here. So I think people are really nostalgic for those kinds of events. And also the fact that these images are from a different era, from the 90s, which adds a whole other level of nostalgia for when life was very different, for a time before social media and the technology we have now. So it ended up being a great time for the book to come out.

For some people, it brought back memories. But I think the younger generations also really kind of long for something like that. They don’t have the opportunity to experience a life like that for themselves, especially not now, when there are so many limitations on how the young can have fun and travel.

If we assume that all processes are cyclical, do you think there could be a “third summer of love” in the near future? Or have social media and the post-pandemic era made that impossible?

I wouldn’t be surprised if some kind of version of a summer of love happens, but I think it would be different from what it was in the late 80s/early 90s. There’s a lot of press in the UK at the moment about there currently being many parallels with that period of time. And actually, there’s been a big surge in illegal raves happening all over the UK. Some of these parallels involve the distrust of our government and the restrictions on and closure of lots of venues and clubs. And then Covid-19 on top of that. But people really have this desire to dance and just be with other people. So yes, I think a third Summer of Love is possible.

I wouldn’t be surprised if some kind of version of a summer of love happens, but I think it would be different from what it was in the late 80s/early 90s.

I’m not sure it would be the same, though, because I don’t think it’s possible to repeat. When something’s brand new, the beginning of a scene – when it’s really new, fresh and exciting – it’s got a different edge to it that you can never really recreate in the same way. Especially now, when we have all this technology and social media. I mean, if we went back to one of those rave parties now, everyone would have their mobile phones out and would be taking a thousand photos. That would take away some of the mystery of it; it just becomes too overdone.

Seana Gavin. New years day, abondoned factory Rome, 2002.

Why did you stop your travels back then? Did you just grow up, or what happened?

I removed myself from the scene after the tragic loss of my best friend. He died suddenly at a party in France. I carried on, attending parties for another year or so, but after he died, that was really the end for me. I guess I started seeing more of the reality, drugs kind of took over the scene, and we lost a few other people as well. I think that was the turning point for me.

I removed myself. I set up my life in London and began living a more healthy, calm lifestyle, and I lost touch with a lot of those people. The book has actually been very healing for me. And I’m now getting back in touch with a lot of the friends from back then. It’s allowed me to focus on the positive side of the scene I was in and remember the good stuff, instead of it just being tainted with how it ended abruptly for me. A lot of people in the book, whom I haven’t spoken with in almost fifteen years, have recently gotten back in touch with me. They’ve really enjoyed looking through it, and it brought back a lot of great memories for them, too, which made me very happy to hear. That was part of the point in publishing it.

What are the main lessons you’ve learned from that period of your life?

I was very young when I entered that scene, so that period reminds me of the thinking you have when you’re that age. Everything was so exciting and new and an adventure. And the fearlessness that I had... I think it’s a good reminder for me to not be uptight. Because when we get older, we get more and more uptight in certain ways and fearful of irrational things. I think it’s just a good reminder of the mentality I had back then. There was a real sense of freedom. I was spending entire summers travelling along with the sound systems. I really lived very minimally. I had a small bag and didn’t have many possessions with me. We weren’t surrounded by mirrors; I was very unselfconscious. So much freedom came along with living that kind of lifestyle. It’s a good reminder to not get so attached to things. Because possessions don’t necessarily make us happy.

Seana Gavin. Seana, Mariannenplatz squat, Berlin, 1996.

And that’s possibly one of the things that Covid-19 has shown us so vividly – that in reality we need very little. Because having lots of things or lots of money doesn’t save us. The virus doesn’t discriminate. It’s interesting that Covid-19 is mostly talked about as something very bad, a terrible calamity that has fallen upon us. But, as we know, the white of the yin-yang also contains a black spot and vice versa. What do you think is, or could be, the positive aspect of Covid-19?

Obviously, the fact that millions of people have died due to the virus is horrible. But I feel that there have been a lot of positive aspects of the virus as well. Like you said, a more socialist equality has emerged. Especially when everyone was just staying at home. The virus forced everyone to stop, like pushing a big pause button. And we were all in the same situation. Before Covid-19, especially in the cities, the pace of things was so fast, and you felt like you had to operate at that same pace in order to succeed. There was always this pressure to succeed, to do well, to make money. But you know, that leads to stress, anxiety, feeling burnt out and not looking after yourself.

Of course, everyone reacts differently. But a lot of people I’ve spoken with were doing lots of exercise, eating healthy food at home, spending more time with their families than they probably ever had the opportunity of doing, and also connecting back to nature and a more simple life. Walking through nature was my main form of entertainment during that period. I mean, I’m lucky to live where I do, because I was able to walk safely without bumping into other human beings and without much anxiety, just really appreciating the simple things. Just watching, for example, the interaction between dragonflies or going for walks with my camera to admire a super moon (there’ve been quite a few super moons during this period!), which has really mesmerised me.

We have started to grow vegetables. I know a lot of people who’ve set up allotments in their gardens and want to be more self-sustainable. I’m sure nature and animals have also benefited from the lack of traffic on the roads. With all the air traffic on hold, air quality improved as well. Pollution definitely decreased. So, there’ve been a lot of benefits from this period of time, and I know many people who say they kind of secretly hope it stays this way for a while. Now that people are starting to go back to work, though, I think it’s quite hard, because they’ve had this break and they’ve been living a more simple, pure life without many of the usual stresses. It’s quite hard to adjust to normal work again. But maybe in some ways things will never really go back to how they were. Maybe some of the changes will stick.

I guess it wouldn’t be a surprise if the younger generations began rebelling against the way things are for them.

But for young people – teenagers and the youth going through all this right now – they’re having quite a tough time. It must be quite strange to grow up with fears and concerns and restrictions, and also missing a lot of school. And all the talks regarding Brexit, which have been going on for a while now. So yes, I guess it wouldn’t be a surprise if the younger generations began rebelling against the way things are for them.

Seana Gavin

You can follow Seana Gavin via Instagram