White canvas is ugly

An interview with artist Michaël Borremans

The Coloured Cones exhibition by Belgian artist Michaël Borremans is on show at Zeno X Gallery in Antwerp until February 20, 2021. Borremans is one of the best-known painters of our time, and his work, which is deeply rooted in art history (any conversation with or about him almost always includes references to Velázquez, Manet and other masters), is characterised by an enigmatic and surreal mood, a mysterious feeling of losing oneself in time and space, as if having difficulty tracking familiar landmarks and stepping into a strange dream. Every stroke of the brush, the corporeality of each colour and substance, its thickness, the fall of light on it, the glare – everything bears significance, and this entirety turns a two-dimensional plane into a breathing space inhabited, in most cases, by strange images. Regarding Borremans himself, it is said that he always paints while dressed in a suit, never begins working on a pure white canvas or page, and once had a studio located in a church. All of which is true.

Befitting the times, our conversation took place via Zoom. Borremans was in his studio somewhere in rural Belgium not far from Ghent. Because “city life is less pleasant than before”. The pandemic was present in our conversation but did not take centre stage. The pandemic has also transformed his present exhibition, which was supposed to open in May. Instead, Borremans continued working on it. As he admits, “Painting is very exciting when it’s at its best.”

Does art have the ability to change people? Does it have the power to make them better?

Seeing art has changed me a lot, but I’m very receptive to it. Of course, not everybody is the same. For me, art makes life worthwhile; if there were no art or literature or movies, life would be the most horrible place imaginable. Poetry and art provide the spice of life. Art makes you reflect in a good way, and it can sometimes lift you up. But I’m very sensitive to paintings. I’ve seen paintings in museums that have made me cry out of... not sadness, but out of emotion.

How do you feel in these uncertain times? Has the current situation had an impact on your art? Your work has always been filled with a strange feeling of mystery, the absurd, impossibility – and now suddenly, all of this has become a part of our everyday life.

Well, I can only tell you that I don’t always know what I’m doing or where I’m going, but I’m definitely convinced that this situation will affect my work. But I don’t know exactly how these processes work, and I’ll only be able to see the potential impact of them on my work after some time. So I do realise it’s going to incubate in the works somehow, I just don’t know how. I can’t see it now, but I feel it. There’s not much more I can say about it, because I realise it’s happening, but I don’t know what form it will take. It’s certainly already in progress, but I will only perceive it later on, because right now I’m still in the middle of it. The pandemic has had an impact on everybody’s life.

I have three studios. Two of them are in Ghent, and one is in the countryside, where I’m mainly working now. Because city life is less pleasant than before. I have this luxury that I can make this choice.

You once had a studio in a church in Ghent.

I don’t have the church anymore, it was a temporary solution. Of course, it’s a pity, but I moved to another studio for large formats, one that has more sanitary facilities and heating and things like that. The church was very wonderful as a place to work, but it was not very comfortable.

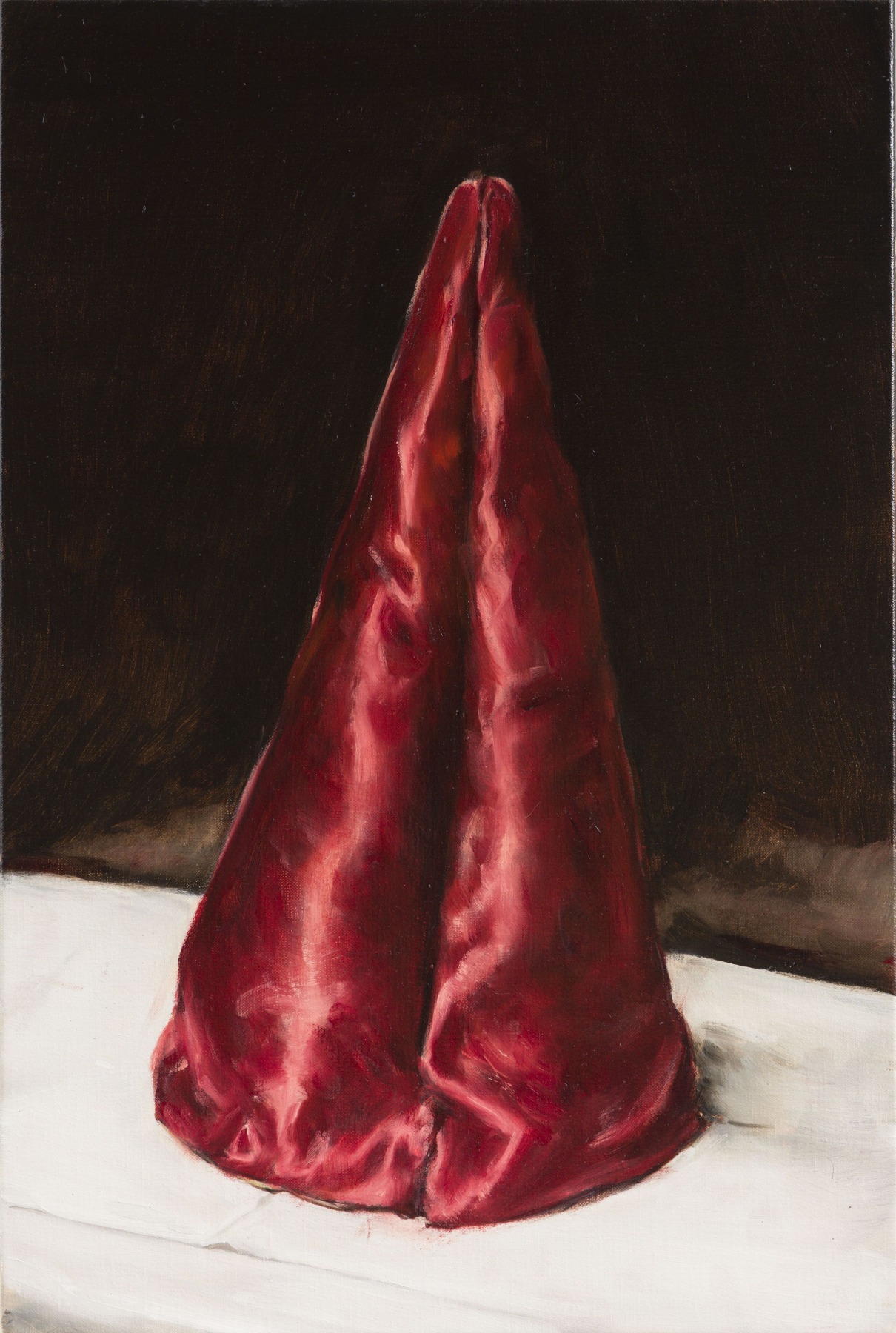

Borremans Michaël. "The Pope". Oil on canvas / 60,2 x 40,2 cm / 2020 / Photographer: Peter Cox / Courtesy Zeno X Gallery, Antwerp

Did the church environment have an impact on your painting?

Yes, absolutely. The church had a very special effect on my way of working, on my concentration, because I was raised Catholic, and for me, churches... even subconsciously you consider it a holy place. I had my canvas where the altar was, you know, on the same spot. That was the best location in terms of light. Of course, it’s all in the head, but for me, it was like a magical experience to work there.

I had my canvas where the altar was on the same spot. That was the best location in terms of light.

“I still like the idea that people come together in a building to reminiscence about life and death.” So you once said when talking about churches and religion. After a fairly long period of time in which we felt super-powerful and tried to avoid thinking about death, existential questions have now suddenly returned to people’s lives. Do you tend to think a lot about death?

Yes, but I often think about it in terms of having arranged things as best as I can for the people around me before I leave this world. So, I try to arrange things, and I’m working on it right now. But these are practical issues.

I’m not afraid of death, but I do hope I can live for another thirty years. Because I want to still do some things in my work, I still have a lot of plans and ideas, and it would be pity to leave before I’m finished.

On the other hand, though, death is the final solution. It’s relieving to know that we have it. I mean, we’re born and then we die, and in between we’re in this place, whatever it is. There’s no escape anywhere. We don’t know exactly what death is, although we probably lose our consciousness and no longer exist, which is fine. I just want to be practical about it, because I’d be leaving things behind. My work and this beautiful country studio, which I’ve been restoring and decorating over a span ten years...

And if someone were to buy it after I’m gone and paint everything white, I’d come back as a ghost and haunt him until he left (laughs)!

Borremans Michaël. "Girls on the Dancefloor". Oil on wooden panel / 22,2 x 29,6 cm / 2019 / Photographer: Peter Cox / Courtesy Zeno X Gallery, Antwerp

Tell us about your new exhibition, Coloured Cones, at Zeno X Gallery.

Here I can see that the coronavirus situation has had an effect. The exhibition was planned to open in May, but it was postponed because of the pandemic. The exhibition was finished, but I kept working on it and making new works for it. So the show has changed a lot from its initial setup.

This whole project came about almost by chance. And the things that emerge by chance are always the best things. This is the task of the artist – when something interesting happens visually, the artist is capable of tracking it, perceiving it, noticing what’s happening. Because we all see the same things, but the artist sees them in a different way or sees interesting things happening with ordinary things because of his or her imagination.

The things that emerge by chance are always the best things.

So, I saw something very uninteresting, like these samples of fabric I had sitting around in the studio in the shape of cones; fabric for another project, shiny, like satin. But then I started portraying them. They’re all different in size and colour, but they’re shiny like satin. And they refer to different characters and different individuals. My attempt was to have the context of a portrait. In Western cultural history, very often over the past several hundred years in portrait painting, the sitters were dressed in their best dresses, which were often made of satin. It was always challenging for the painter to portray this material, and it was to show off his mastery. That was not important to me; I just wanted this kind of rhetoric, this implicit link with Western cultural history in portrait painting.

Borremans Michaël. "Coloured Cones". Oil on canvas / 88 x 120 cm / 2019 / Photographer: Lieven Herreman / Courtesy Zeno X Gallery, Antwerp

It was very difficult to make the paintings interesting, because the subject is almost nothing. It’s just a cone of fabric. It was technically the most difficult thing I’ve ever had to do.

It was very difficult to make the paintings interesting, because the subject is almost nothing. It’s just a cone of fabric. It was technically the most difficult thing I’ve ever had to do.

For you, is painting something you do and control with your mind, or is it more of a spontaneous, unrestrained process? Where are you when you paint – in the reality of the studio or somewhere else?

Preferably, I’m inside the painting when I’m painting. But being totally in a painting is hard to achieve. If it happens, though, it’s wonderful. And if it doesn’t happen, it’s can be dreadful, because you can get dark thoughts while you’re working, and you don’t want that to happen, because it has a bad influence on your working process. But painting is very exciting when it’s at its best. I mean, that rarely happens, but when it does, it’s an exciting place to be – when you’re totally in the painting, and you feel the paint and you feel that... It’s difficult to describe, but it certainly gives you a kick, and it’s addictive. But the execution of the painting is really only the last part of a long process. Conceiving the idea and developing the concept for a painting can sometimes take years. Sometimes it takes a day, sometimes it takes two months. Sometimes things simmer for a very long time.

And that’s why I like to have different studios, because I can leave works everywhere and come back after a month or whatever. Here at the country studio, it’s even better, because I have different rooms where I work. Right now I’m occupying five rooms, and I can work on something, then close the door, lock it and go back in two months to check if I’m still seeing it with the same eyes or with different eyes. And to see if I’ve come up with an answer for a specific problem I created in the painting. This is something that suits me very well. Some artists work with assistants; I work with different studios and just do my tours of them.

Conceiving the idea and developing the concept for a painting can sometimes take years.

You do everything by yourself, without an assistant?

I actually have two people who assist me with practical things. But I do all of the painting myself, even the preparation of the ground layers, even the cleaning of the brushes.

Borremans Michaël. "Conehead". Oil on canvas / 36 x 30 cm / 2020 / Photographer: Peter Cox / Courtesy Zeno X Gallery, Antwerp

Do you believe that you can transform your energy and transmit it to a viewer in some way through gestures, through physical touch?

Yeah, absolutely. It’s absolutely like this. Of course, that’s a romantic viewpoint that doesn’t really fit with a conceptual attitude, but I think... I’m very hybrid in these things. It’s very true that, in the medium of painting, every individual can develop his or her own signature or style. Not everybody can do this, but if someone wishes to, it is possible. So painting is always a very, very personal thing.

Of course, I have colleagues who do not execute paintings themselves, but that’s also not a problem, because it fits their philosophy of conceiving a work of art. We live in times when very different ways of working are accepted, which is a good thing. Painting is only a medium. Some artists’ work can be perfectly executed by someone else, but not my work. I’ve tried it.

Painting is always a very, very personal thing.

How does painting fit into the frame of contemporary art? Painting has been declared dead many times. It’s not found very often in the big, prestigious exhibitions.

Yeah, I realise my work is not accepted in certain surroundings, it does not seem to fit in a fashionable way, what I believe to be a good thing. But the reason might also be the fact that there’s not that much interesting painting going on today. I’m not very interested in the art world or what happens in it. But I consider myself clearly a contemporary painter. I use an old medium, but it’s just a fucking medium. Photography will be ancient one day, too. Modern media age much faster than old media. But painting is always discussed, which is ridiculous. But that’s because we have a lot of very bad painters nowadays.

I don’t really want to be mainstream, so it suits me fine, you know. It’s not like you have a choice in these things. You are who you are. As an artist, you cannot plan what kind of artist you’re going to be. For me, there was never any other way – I’m this artist that I am now, and it was never a choice. It’s just natural.

I consider myself clearly a contemporary painter. I use an old medium, but it’s just a fucking medium.

You came to painting when you were already about thirty years old.

Thirty-four. I only did drawing and some graphic work before.

What was the trigger that turned your attention to painting?

Well, one day I had an epiphany. I was in my studio and starting a new work, and... something strange happened... I realised no, no, that won’t do. All of a sudden I saw the light – I want to be a painter. So then for about four, five, six years I painted only for myself, before I showed anything. I was teaching back then, so I had an income. And when I thought my painting was OK, I quit teaching and tried to live from my work, which I did successfully.

You never paint on a white canvas. Why? Does a new beginning scare you?

No, white canvas is just ugly. It’s just white. It’s blinding. If you give a certain colour to the surface of a canvas, then you already have a starting point. I try to make my canvases beautiful.

Before I start to do a painting, I make a monochrome painting. Some of them are so beautiful that I find it a shame to make another painting on top of them. So I have a series of monochrome paintings in my stock that I will never paint on. And when I’m old, I’ll make a show with my monochrome paintings. So that’s how versatile I am (laughs). I feel like there are different artists living inside of me. One has the leading role, of course, but I try not to neglect the other artists in me or the other viewpoints I have in art. Because every attitude you have as an artist restricts another attitude. That’s the sort of thing I tend to think about sometimes.

My drawings are totally different and have more to do with cultural ideas in the public space and things like that, whereas the paintings are much more introspective and more... simplistic or minimalist? I also flirt all the time with ideas for sculptures, but I have no time to execute them.

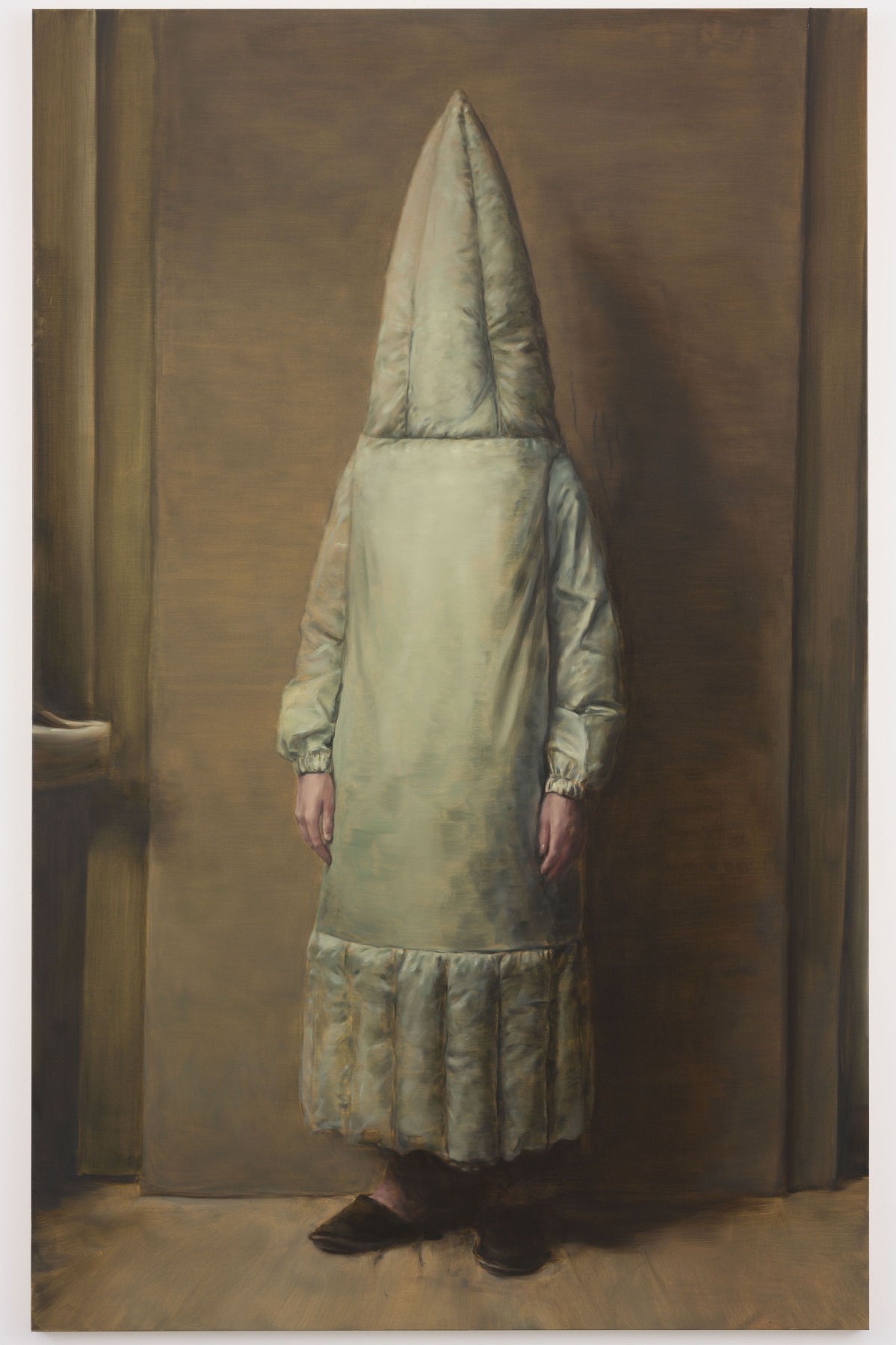

Borremans Michaël. "Large Rocket". Oil on canvas / 300 x 190 cm / 2019 / Photographer: Peter Cox /

Courtesy Zeno X Gallery, Antwerp

In some way, your cones are sculptures, too.

Yes. They’re so beautiful. I have them here on my table and I enjoy them. I have to place them in other scales and in other contexts. These are experiments, but I have to try.

I’m very happy with my cones. Some of them are more beautiful than others, just like humans. So maybe I’m going crazy and these are my new friends (laughs).

I’m very happy with my cones. Some of them are more beautiful than others, just like humans.

Speaking of beauty, there’s a strong presence of it in your artwork. Although maybe the beauty is a bit strange, surreal, frightening... What does beauty mean for you? Is it important to you?

It is important, but it’s not the most important thing. In my painting, the element of beauty is important in the sense that it has different functions. One of these is to draw the viewer to the work.

To make the work appealing. Beauty’s not the goal; it’s a tool to get the viewer’s attention. I’m not sure if I succeed in doing this, but that’s what I try to do. So, this is one function of what we can call beauty. It has a function to seduce.

But then sometimes there’s another beauty in the paint itself. I can enjoy the beauty in a painting style and the way the paint is applied to the canvas and how you see the strokes and the pentimento and so on, and that can be very beautiful. But that’s a beauty more like poetry, and that’s real beauty. This is what I really appreciate a lot in paintings in general – if the paint becomes poetry. I’ll give you an example: if I look at the still lifes of Manet, such as flowers in a vase, which is a very vulgar theme in painting (by the way, Manet had his own take on this subject), it’s pure painterly poetry. It’s the definition of painting, or what painting should be. To me, that’s really beautiful and very appealing, but it’s not the beauty I would use to seduce, just the beauty that can move a person.

Borremans Michaël. "Dodgy Bob". Oil on canvas / 60,2 x 44 cm / 2020 / Photographer: Peter Cox / Courtesy Zeno X Gallery, Antwerp

And then there’s maybe a third element of beauty, if we can call it beauty, and that’s introspection. I try to be introspective in painting, to have a certain silence in the image. Like you have in a church, or like the quality of an icon. In other words, I try to create an image that is not just an image. An image that is also a painting, of course, but one that gives you more than a regular image would, one that radiates something or has soul, which is a very wrong word to use these days in art. I want to create an image that just sticks out and doesn’t leave you alone. That could also be due to something irritating I put into the work, or an element of beauty. It can be both.

I try to be introspective in painting, to have a certain silence in the image. Like you have in a church, or like the quality of an icon. In other words, I try to create an image that is not just an image.

Beauty can also be irritating from a contemporary viewpoint, which I find very interesting. Yes, beauty is a complex given in artwork, and it functions in different ways, but it is important, of course.

And what about the image?

The image, the subject, the conceptual part of a work – that’s also important. Why I paint this subject in this manner and in this style and present it in this context. I think painting has been conceptual ever since Marcel Duchamp. Unless you make old-fashioned paintings. Painting has been declared dead many times, and a lot of painting we had before is totally no longer relevant. If I paint your portrait, that’s no longer a relevant way to use this medium; it’s old-fashioned. Painting has now been relieved of all its functions, from the documentary function it had in the past.

So painting is free now. We can do crazy things with painting. We can do things like Magritte, who was a very conceptual painter, and Man Ray made some interesting paintings. I think the medium has become much more exciting precisely because part of it has died now.

Painting is free now.

You’re deeply connected to art history. What’s the most important thing you’ve inherited from it? You mention Velázquez very often.

I looked at a lot of his work because his style of painting was most appealing to me, also technically. It suited my temperament, because I cannot work very slowly. I always stand up when I paint, and I paint rather quickly. You don’t see it if you look at one of my paintings, but I need to paint fast and be very concentrated. It gives the work energy if you paint fast. If you paint too slow, then the world becomes slow, too.

One of my favourite painters is Jean-Siméon Chardin, who was a Rococo painter and whose work was also a bit romantic, but today it’s very much appreciated because it has a contemplative quality. If you’d ask me if I could have one work of art from the whole history of painting, I’d want something by Chardin. But I cannot do his style of painting. I have a different temperament than sitting down with glasses. I cannot sit still. I’m energetic when I work.

Is the physicality of painting important for you?

Painting is very physical. Even when painting on a small scale, I paint with my whole body. I really do. I move around even when I work at a table. It’s a kind of energy, and the energy goes into the painting.

Do you always wear a suit when painting? That’s what people say.

Sometimes, yes. That’s the legend, but that’s who I am.

Sometimes I dress up like a woman to see if it has an influence on my work.

And, does it?

Yes. It’s difficult to walk around in high heels (laughs). I’d like to have a female police uniform and see what kind of painting I’d make then (laughs again, adding “that’s a joke”). But I tried it a couple of times, and I once also tried to make a painting dressed like a rabbit.

And?

An artist should never avoid experiments, you know. But unfortunately I didn’t see much difference in the paintings. That would be exciting, though.

That would be too simple.

It has no influence whatsoever, I’m afraid.

An artist should never avoid experiments.

Sometimes you cover the faces of your images. Are you trying to make them more anonymous?

I made a series of works with the faces totally covered. I used costumes that cover the whole body and are used in the film industry to film movements against a green screen. I don’t know exactly how it works, but I found a couple of these costumes and decided to include them in some works, because it’s interesting to make a portrait of someone who looks totally anonymous.

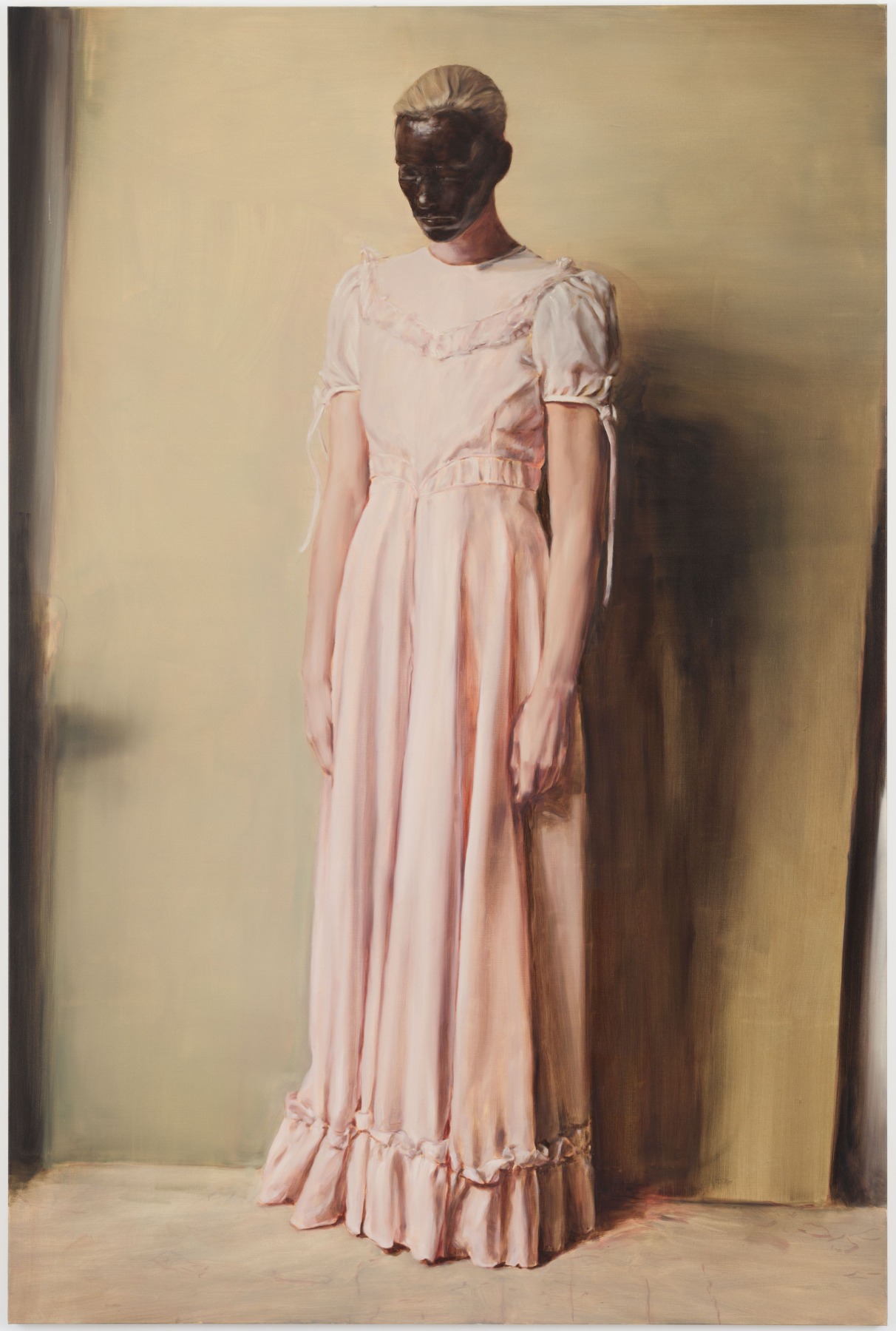

Borremans Michaël. "The Angel". Oil on canvas / 300 x 200 cm / 2013 / Photographer: Peter Cox / Courtesy Zeno X Gallery, Antwerp

And how about Angel (2013), which seems to be one of your best-known paintings – a woman in a pink dress but with no face. Or rather, her face is hidden by a black “mask”, which makes her unrecognisable.

I painted her face first.

Why?

Oh, that was a very intuitive decision. That was back in the church, when I was looking for a model. I had this Disney princess dress. It was very large-sized, so I had to find a tall model who could pose for me. For some reason, while she was there, I had the idea that I should paint her face black. Because everything was pink and white, and I wanted to make an image. And she was a bit androgynous, you know, with short hair and a bit male-looking. With the black face she’s like a compression of gender and race. Compressed, in a way, and dressed in a nice pink dress.

You painted her in the church?

Yeah, and it was very magical when I took photographs of her and when I painted her face. I was... it was just a good moment. Sometimes you just know in the moment that something good is happening.

Sometimes you just know in the moment that something good is happening.

Do you still use photographs as sketches for your paintings?

Always. My photos are my sketches, my studies. Before I work on something, I make a lot of photos. I try different colours, different lights, different poses before I get it right. It’s really an important part of the process. And then the painting is the last part, but it’s the most important part, of course. You’re making a painting based on the photo or on different photos, and that’s always... it works or it doesn’t work. You have a fifty percent chance that it will become interesting. Because the painting is different than the photographs, which are not interesting in and of themselves. You have to make them interesting in the painting.

When I make photos, I’m already painting and I see a painting in them. So the photographs themselves... they look strange. They don’t look like photographs, they don’t look like paintings, and they’re not really interesting. But for me, they’re a good tool to work with. That’s how it developed in my case, because I want to make original images. In the beginning I did work that was based on images I found here and there. The basic images were not mine. But then I wanted to conceive the images all by myself.

And at what point do you know a work is “finished”?

I don’t know how, but I always know when it’s finished. I never have doubts about whether it’s finished or not. Well, to be honest, sometimes I do, but mostly not. If I have doubts about the painting, about whether it’s good or not, the fact that I have doubts means that it’s not good enough. I have to be 100 percent convinced that I can not do it better. I destroy a lot of work that’s almost very good, but... not good enough for me. So I’m very severe, and I’m very selective.

If I have doubts about the painting, about whether it’s good or not, the fact that I have doubts means that it’s not good enough.

You once said that a painting can be like a knife in the eye. Can you explain what you mean by that?

That’s what someone else said – this knife in the eye. I forgot his name. He was a famous curator in the 1980s, and he said to me: “I thought you were a very bad artist, but now I see your show. You’re a very good artist. Your work is like a knife in the eye.” He was very conceptually minded, but he saw the true vocation of my work.

Borremans Michaël. "Merry Missile". Oil on wooden panel / 21,5 x 14,8 cm / 2020 /

Photographer: Peter Cox / Courtesy Zeno X Gallery, Antwerp

Tell me about your films – although I’d probably call them reanimated paintings instead of films.

I’ve only made a few. Maybe seven. Just recently I’ve been working on one with the cones, in which the cones are dancing. They do a Renaissance dance, a court dance, very beautiful. But I have to do other music for it, not Renaissance music. I want to make the music myself.

You were a member of the Singing Painters group.

I quit, but they replaced me. I grew tired of it because we were not developing anymore. But they attracted other musicians, and now they play more jazz music. We used to do more like noise and punk rock. But I do music by myself now and with some other musicians.

Does music mean a lot to you?

I play music every day. When I take a break from painting, a lot of times I pick up my guitar. I have instruments in all my studios. I find it very relaxing. For me, playing guitar is like meditation might be for someone else. Because I’m so bad at playing guitar that I need to put all my focus in it, and then my mind can relax. I cannot think of other things while I’m playing. I’m not the best player, but I love doing it.

You once said that it’s better for an artist to be poor. Why?

Maybe I’ve changed my mind. I find it good to have money. It’s very practical and comfortable. Then at least you don’t have to worry about money. But it is true that young artists... Well, you can fund young artists occasionally, but not structurally, because if you do that – and it’s been proven in the past – you get more artists and more mediocre work. If you don’t fund them, you have fewer artists and better work. It’s tough for the artists, but I believe that to be true.

In funding artists, you have to select which ones, because some artists are capable of making money with their work, while other artists (such as performance artists and so on) aren’t. And they need support, of course. I think artists should have something like a union. Like actors have, so we can pressure governments to support art in the right ways, because right now we’re all individuals and we’re not very well organised.

Title image: Michaël Borremans. Photo: Alex Salinas