Freedom of Thought without Freedom of Speech

A conversation with Abdulnasser Gharem, Saudi Arabian conceptual artist and former lieutenant-colonel in the Saudi Arabian army

‘It's not of paramount importance whether a gallerist finds your artwork good or not. Important are the causal questions and how they are answered: Are there still paradigm shifts in art? And who can work these out?’ is how Berlin gallerist Christian Nagel encouraged an audience of fine art students to think more deeply about what a successful artist's career means. ‘In Sharjah, UEA, we were in conversation with Abdulnasser Gharem from Saudi Arabia. He already has quite a long history, previously having been a lieutenant-colonel in the Saudi Arabian Army for more than two decades (before retirement in 2014). As a conscientious objector, it was a moral question of whether I could represent this artist's work or not. There are no conscientious objectors in Saudi Arabia. In this way, a gallerist encounters unusual positions that stimulate reflection or reconsideration that go beyond the edge of the Western world,’ Nagel continued. His example immediately caused my neurons to fire: firstly, how much do I really know about Saudi Arabia's cultural scene other than the antipodes: the Saudi Crown Prince's highbrow purchase of Leonardo Da Vinci's Salvador Mundi for a record-breaking $450.3 million in 2017, and the fact that art production is virtually impossible under the country's local laws. The seemingly contradicting strands of heavy censorship, politics, and the generous investments of Saudi Vision 2030* for creative economics raised another question regarding how the concept of artwork can evolve to a level that presents a new contribution and perspective to the Middle East and to contemporary art.

Abdulnasser Gharem / As one of the co-founders of the art movement Edge of Arabia, Abdulnasser Gharem has become one of the most important promoters of contemporary Saudi art, bolstering art education at home and encouraging its exhibition abroad.

Abdulnassser Gharem (b. 1973) is an internationally acclaimed self-taught Saudi conceptual artist who lives and works in Riyadh. Spanning a variety of mediums – including photography, video, sculpture, painting, and performance – Gharem's work challenges the artistic conventions and prejudgements of modern-day Saudi Arabia. The artist catapulted to fame following the April 2011 record-breaking auction at Christie’s Dubai. His thought-provoking sculpture Message/Messenger (2010) – which uses the Dome of the Rock in an allegory for the peace process – still holds the record for the highest sale of any living Gulf artist. He donated the proceeds to the Edge of Arabia campaign to foster art education in his native country.

As a former lieutenant colonel in the Royal Saudi Arabian army, issues such as authority, control, and the notion of freedom can be traced throughout his body of work. Quoting Saudi art collector and curator Basma Al Sulaiman: ‘Abdulansser is not opposed to the government. Though he is disciplined and courageous, he is not aggressive and he is not trying to break the rules. He has conviction, yes, but he has subtlety, too, and respect. In Saudi Arabia it's hard to achieve anything without these. That's what's so clever about him and his art.’

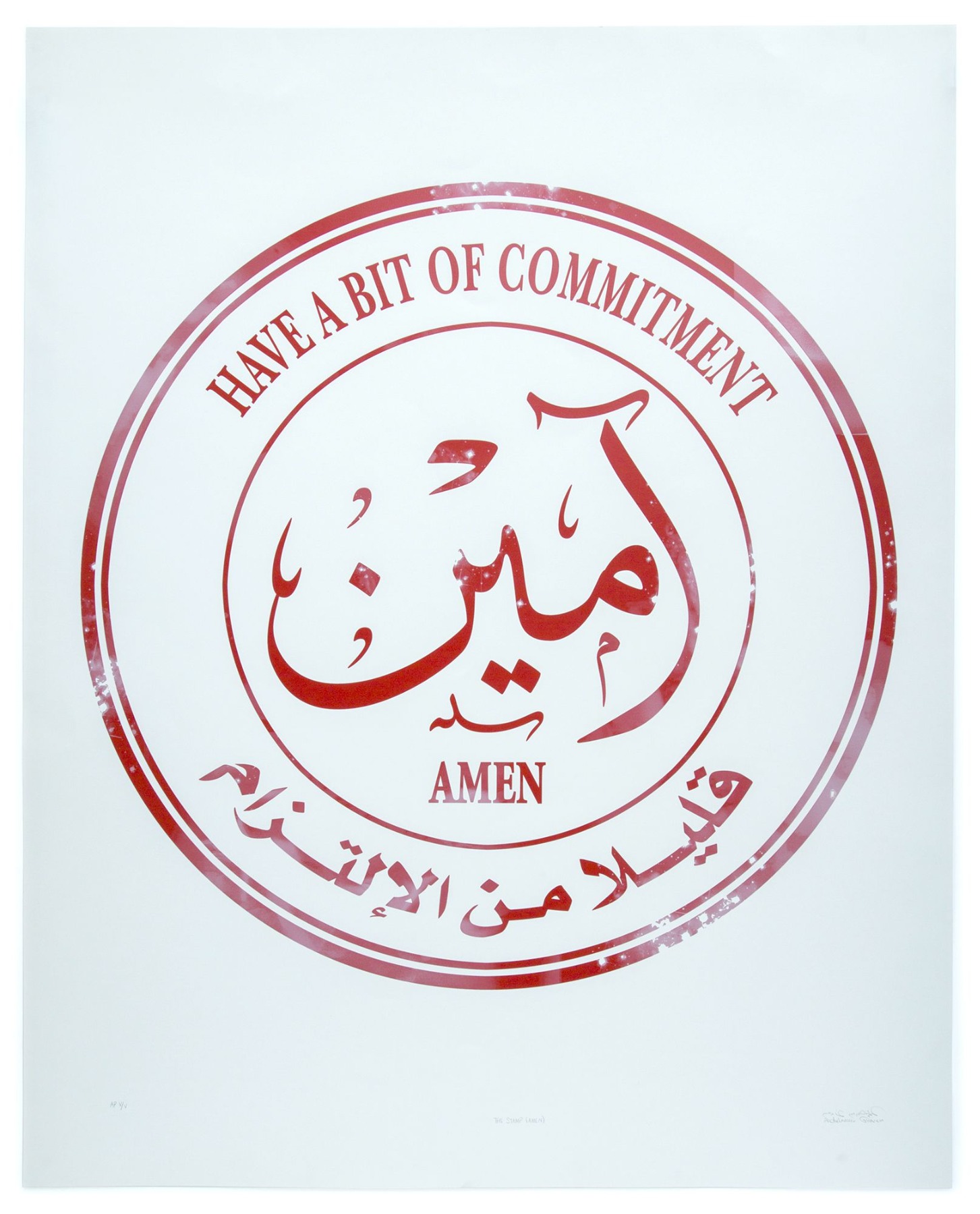

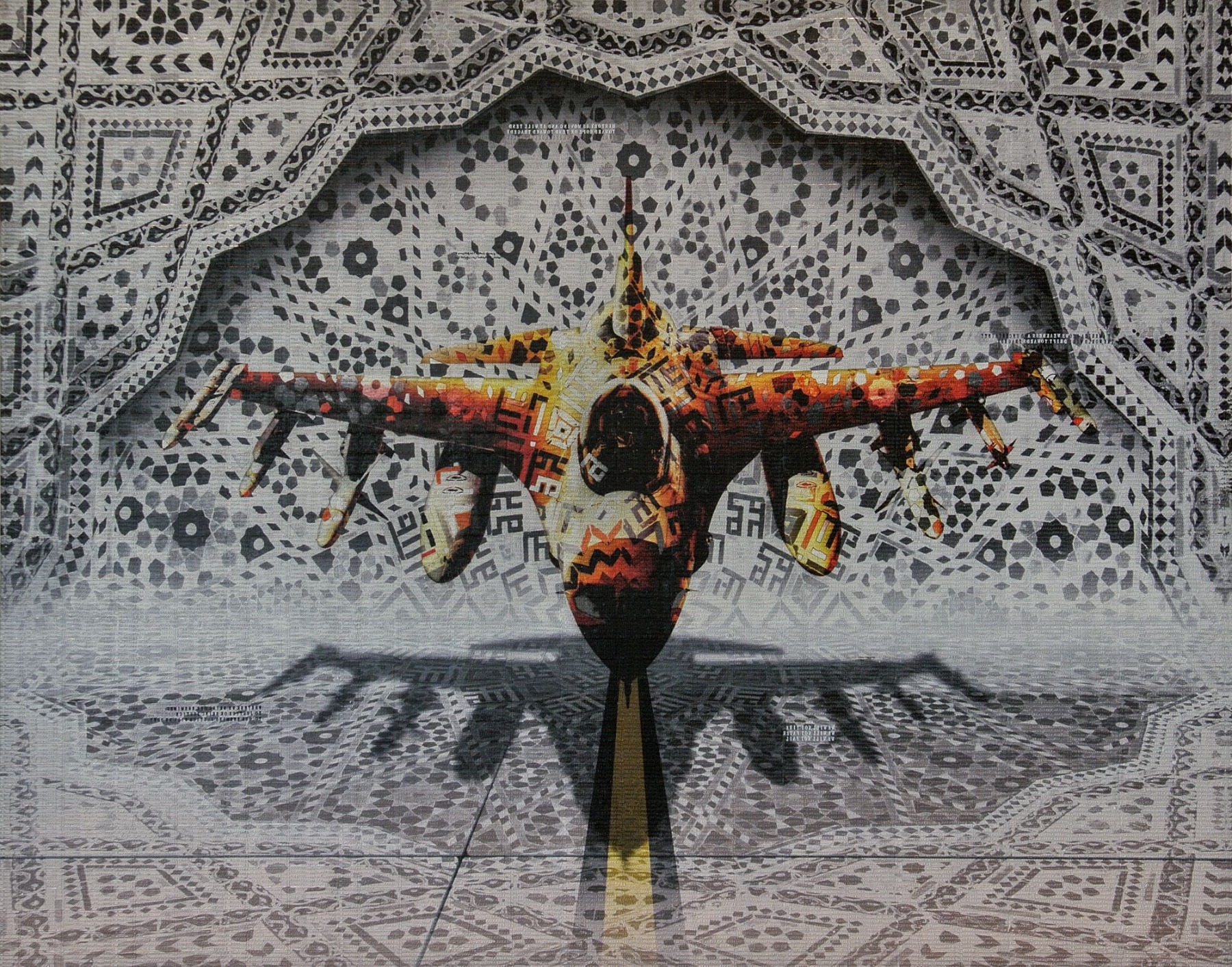

Gharem’s vibrant 'rubber-stamp paintings', as he calls them, hold hidden (mirror-inverted) politically and socially astute messages in Arabic and English. The painting Pause II (2016) is the artist's personal reaction to the terrorist attacks on September 11, 2001, which have laid the foundation for much of his body of work. ‘To me, 9/11 was like a pause,’ says Gharem, explaining how, to him, the Twin Towers resembled a pause sign on a TV remote control. 'It was like the whole world just stopped (and asked): What's going to happen now?’ When he later found out that two of the hijackers were his classmates, he wondered why, with the same early education, they had chosen this horrific path in life.

The Process of Stamp Painting | PAUSE II from Gharem Studio on Vimeo.

As part of his response, Gharem and his brothers have been running collective workshops since 2013 for young Saudi talents who have artistic instincts but not the environment in which to implement them. His studio is a place where emerging talents can think individually, survive and thrive together. This is vividly captured in his video work Aniconism (2015), a satire of an achievement that should not even be an achievement. It shows a group of male art students in traditional dress participating in a painting class – they are using as their model a nude female mannequin that Gharem bought in Dubai. To get it through Saudi Arabian customs, the artist had to dismantle the mannequin and divide the pieces among different pieces of luggage, thereby hiding its true nude form. ‘The film shows the will of artists in the country to engage with the aesthetics at the core of art history. I believe this is the first time that art students in Saudi Arabia have drawn a female figure as such,' Gharem explains.

The Story Behind Aniconism from Gharem Studio on Vimeo.

Taking on the role of both mentor and financier, Gharem teaches his students one thing above all: to be free in mind, even if not everything can be said openly in Saudi Arabia. According to Gharem, 'Arab nations are in need of independent thinkers’, and that what is needed are more individuals who can think outside of their own cultural lens, not daredevils who believe that a pebble can topple a carriage. Social changes in an ultraconservative country that has just begun to reform itself should take place gradually, and spaces for criticality are therefore pivotal.

Abdulnasser Gharem and I recently spoke via Zoom, each on our own side of the computer screen in Riyadh and Berlin, respectively. A curious mind knows no limits or physical borders, unless you aren't human. In the currently delicate worldwide socio-political climate – where nothing has a stronger influence on opinion than media news feeds – we need to self-educate ourselves by remaining unconditionally curious and, if possible, learn from life rather than from search engines. Especially when right-wing populism has found contemporary art to be a venue that can also be exploited. Gharem's curiosity breaks new ground, not only in terms of art and activism but also as something completely different that could divert ‘bored’ young Saudis from engaging in jihad. I'm confident in saying that Adunasser Gharem has redirected the trajectory of recent Saudi Arabian art history. I hope that these artistic manifestations that transcend the boundaries of freedom of expression in Saudi Arabia’s complex matrix of ideologies will bring about the change that Gharem has envisioned.

Abdunasser Gharem has exhibited in Europe, the Gulf States, and the USA, including at Gropius Bau Berlin, LACMA, The Victoria and Albert Museum, and the Louisiana Museum of Modern Art, as well as at the Venice, Sharjah and Berlin Biennales.

SUBVERSIVE FORMS OF SOCIAL SCULPTURE at Sharjah Art Museum / Abdulnasser Gharem. Concrete Block (2018) © Abdulnasser Gharem

SUBVERSIVE FORMS OF SOCIAL SCULPTURE at Sharjah Art Museum / Abdulnasser Gharem. Hemisphere II (2018) © Abdulnasser Gharem

As a former officer in the Royal Saudi Land Forces, you have no doubt experienced times that are much harsher than the current lockdown going on due to the pandemic. How did you spend the lockdown earlier this year?

That is very true.

During this time in which we had to adhere to strict distancing protocols, I could peacefully read books from cover to cover. I finished reading two thick books of Dante Alighieri's writings translated into Arabic. This could be only possible during a confinement (heartily laughs). A book I would recommend to others is The Theory of Communicative Action by the German philosopher Jürgen Habermas.

We are living in a digital age of rapid communication. Everyone should acquire additional tools to effectively deliver their message, including passing their ideas through artwork.

Just as the pandemic started, I began to set up my new studio space in Riyadh. It is much bigger than the previous space. Now we are organising the library.

Currently eleven artists – men and women – are practising art at Gharem Studio. They aren't my team. These are a bunch of talented individuals, including musicians, a fashion photographer, and a performer. This is not a residency but a long-term collective for young artists, some of whom have been practising art with me for five years. Artists need to be around each other in our country.

The hardest part, of course, was to distance yourself; not just from society but also from those closest to you, since everyone could be a carrier of the virus. It was a good lesson for everyone to care for others in a very simple way.

Aniconism (2015) © Abdulnasser Gharem![]()

Is it common to work in shared artist studios or workshops in Riyadh?

No, it is not. In Riyadh there is no such thing as a salon-like gathering space where one can exchange ideas with other artists – a place with its own library of specialised books on art and culture, and where you can have photography and drawing classes. Artists work under different conditions that require finding alternative solutions together.

Some years ago I took printmaking classes for five months in Spain, just to understand the medium itself – the processes involved in producing a lithograph, etching, woodcut, silkscreen, the significance of different paper, what is hard press, cold press, etc.

Now, everything that I learned there – the theoretical and practical knowledge – I’m passing on to younger artists who want to try their hand at printmaking. I became a link for them to a practice that's not accessible to them here in Riyadh.

When looking at Goya's etchings in museums, I can explain to students how certain things were acquired.

In Riyadh there is no such thing as a salon-like gathering space where one can exchange ideas with other artists. Artists work under different conditions that require finding alternative solutions together.

In retrospect, how did you master this unusual double life – a full-time career as a soldier and an artistic practice, both of which require a high degree of self-discipline.

In the beginning it was very hard. As an officer, I was busy beyond words, but producing art both begins and evolves in the mind. The time spent in the army provided me with a lot of important subjects and ideas that I would later go on to manifest in my artwork. I saw a lot of wars.

I remember sometimes sleeping for only one hour because I was in the army during the day and I did art at night. I am grounded when developing work. Art is not about aggression or how strong one is.

Finally, I'm now a full-time artist. Actually, since 2014. These last six years have been equal to 23 years spent in the army – a very exciting and busy time.

I remember sometimes sleeping for only one hour because I was in the army during the day and I did art at night.

Is it a challenge being a full-time artist in Saudi Arabia?

When I started in the 90s, it was not possible to make a living as a full time-artist in Saudi Arabia. Now it's possible; however, you have to be exceptionally good at what you do.

You are not the only artist in your family. Gharem Studio is run by you and your brothers. What is the relationship between your individual practices?

I have two brothers – one is a musician and the youngest, Aljan, is a visual artist. Together we are 11 siblings.

These things usually start in the household during childhood. As they got older, I took my siblings to exhibitions abroad. When we started Edge of Arabia, Ajlan was very young. He assisted us, learned in the process, travelled with us, and eventually worked as a member of the movement.

In 2014 he showed me a sketch of a project titled Paradise Has Many Gates, and asked me what I thought of his idea. I believed in it and said let's do it. We built Ajlan's cage-like installation in one day in a desert outside of Riyadh, documented it with film and photos, and dismantled it on the same day so that no one would see us.

Paradise Has Many Gates (2014) © Ajlan Gharem

Could you elaborate?

We had to dismantle it because people would protest – a mosque is not a cage, etc.

Currently the installation Paradise Has Many Gates is on view at the Vancouver Biennale.

It took some years for Aljan to come up with good ideas. He had many ideas before, but I knew that he could do better.

It takes time for artistic maturity to be reached.

And this is what I'm telling younger artists – guys, calm down. We are not looking just for a new work of art but for a new concept / new perspective!

Somehow this story of Ajlan's ‘mosque’ reminded me of the incident when Venetian authorities shut down the working mosque installed by Swiss artist Christoph Büchel as part of his presentation for the Icelandic Pavilion in the 2015 Venice Biennale. What are your views on this episode?

I think that Büchel's presentation was amazing. Ajlan's installation talks about religion needing to be transparent. You know what kills good ideas/intentions? Demagogic speech like that by Emmanuel Macron in late October of this year. He didn't choose the right word – he attacked Islam as a religion, but not extremism, which does not represent Muslims. Such inconsiderate statements make people nervous; it infests people with fear – strategically – before elections. Who is he to publicly scorn a religion?

In terms of free expression in art, how can the far-right be countered from entering without sacrificing the very thing that makes contemporary art what it is?

For me, limitation in free expression is a privilege. It makes me think more. It should not kill creativeness. Back in the 17th century, the Jewish thinker Baruch Spinoza was disliked by both Christians and Jews; nevertheless, he became a great and appreciated philosopher. With that said, everyone has their own conditions. Heavy censorship exists not only in Saudi Arabia but also in China, Russia, and Egypt. Regardless, you have to understand your environment and simply be realistic and smart.

For me, limitation in free expression is a privilege. It makes me think more. It should not kill creativeness.

The seemingly contradicting strands of Islamic censorship and the Saudi Vision 2030 endeavor raise questions about the interactions and boundaries between the fields of contemporary art, politics, economics, and religion. Could you comment on these generous state investments for diversifying the arts and culture?

There are many good things in the blueprint of Saudi Vision 2030. I find the updates in the education programme especially positive. Recently authorities allowed philosophy to be a subject at school. That is very promising. Musicians are free to perform music. Boys and girls can go to concerts and take classes together. Women are now driving and allowed to be in public without the veil. It has been only five years since the relaxing of some of these restrictions. In the beginning these were major steps for families raising daughters, but now this is almost mainstream. In my opinion, these are great, long-awaited changes.

Who do you think are better drivers in Riyadh, men or women?

Give me one year to answer this question. (Laughs)

There are imperfections in Saudi Vision 2030, too. They are not focusing as much on education as on commissioning impressive museum buildings designed by some of the world's most famous architects. What's the point of building museums without people having a proper cultural education? This summarises the problem of Saudi Vision 2030 from where I stand.

Another problem – there are inevitable restrictions in the types of art that will be endorsed. A local artist is granted government support only if he or she becomes a part of the regime's campaign, so to speak. If you do not agree to contribute to propaganda that delegitimises divergent opinions, you fall out of favour. A lot of good positions won't be included in their programme.

But it is a good thing, in a way.

What's the point of building museums without people having a proper cultural education? This summarises the problem of Saudi Vision 2030 from where I stand.

Is it?

Yes. Artists struggle, but therefore we are on a quest to find other solutions. I had to learn how to write project concepts and convincing proposals in order to attract funds from the private sector, from people who believe in us.

Capital Dome (2012) © Abdulnasser Gharem

There is a well-known credo that I like to remind myself of, as well as point out to my peers and the people I work with – Every limitation is an inspiration.

Is that what motivated you to establish the art movement Edge of Arabia?

We started to think about Edge of Arabia in 2003, but the first show only took place in 2008, in London. We realised that it was not possible to work in our country on the scale that we would like to. As I probably already mentioned, we don't have a developed art infrastructure, there’s very little formal art education, and freedom of speech is nonexistent. Edge of Arabia was created in order to seek opportunities for advancement and exposure outside of the country.

We reached out to the private sector for financial support. We learn how to do things while in the process and simply by doing: how to write convincing project proposals, exhibition concepts, educational programmes, etc. When local art collectors saw that we were planning to go for the Venice Biennale, they immediately jumped on board, as if they were just waiting for the right person who is qualified enough to take the first move. These are art collectors with a discerning eye and refined taste. They are guests at the biennials, they visit art fairs abroad. We became free from government influence.

It was an amazing experience and a long-needed move at the time. I would say the biggest achievement for us was the exhibition at the Saudi Pavilion at the 2009 Venice Biennale.

One of the members of Edge of Arabia, Ashraf Fayadh, was arrested and jailed by the Saudi Arabian court on charges of apostasy in 2015. What went wrong in his case?

Ashraf is a poet. He is not free yet, but eight years jail-time is better than a death sentence.

He wrote a book but published it in the wrong place, in Riyadh. We reached out to many institutions outside of the country for help, including Human Rights Watch and the American ambassador. Writers and artists in many countries took part in an initiative to support him. We are still working on his release. Hopefully we will soon have good news.

Was this the only incident involving a member of the movement?

Yes. Afterwards we focused more on working outside of the country.

Note that a visual language is open to many interpretations and it is less harmful compared to the spoken word.

A visual language is open to many interpretations and it is less harmful compared to the spoken word.

Has there been a backlash in Saudi Arabia concerning what you have shown outside of the country?

Oh, yes.

I'm curious about your work The Safe (2019)**. I first saw the installation in the Unlimited section of the last Art Basel show. This autumn the work was displayed again during Berlin Art Week.

I'm not showing The Safe in Saudi Arabia.

The show in Basel was an amazing experience... and a bit scary, too. Saudi authorities were upset with the installation. They did not know what to do, how to respond to the display. Back then, I became a little bit nervous. In the end, of course, everything was good.

I deliberately did not give interviews to the New York Times or Bloomberg in order to avoid the story being used for their propaganda against my country.

Other than that, I was glad to see so many visitors queuing in front of the entrance of the installation. I had to ask the fair crew to usher visitors through it in roughly 40-second intervals.

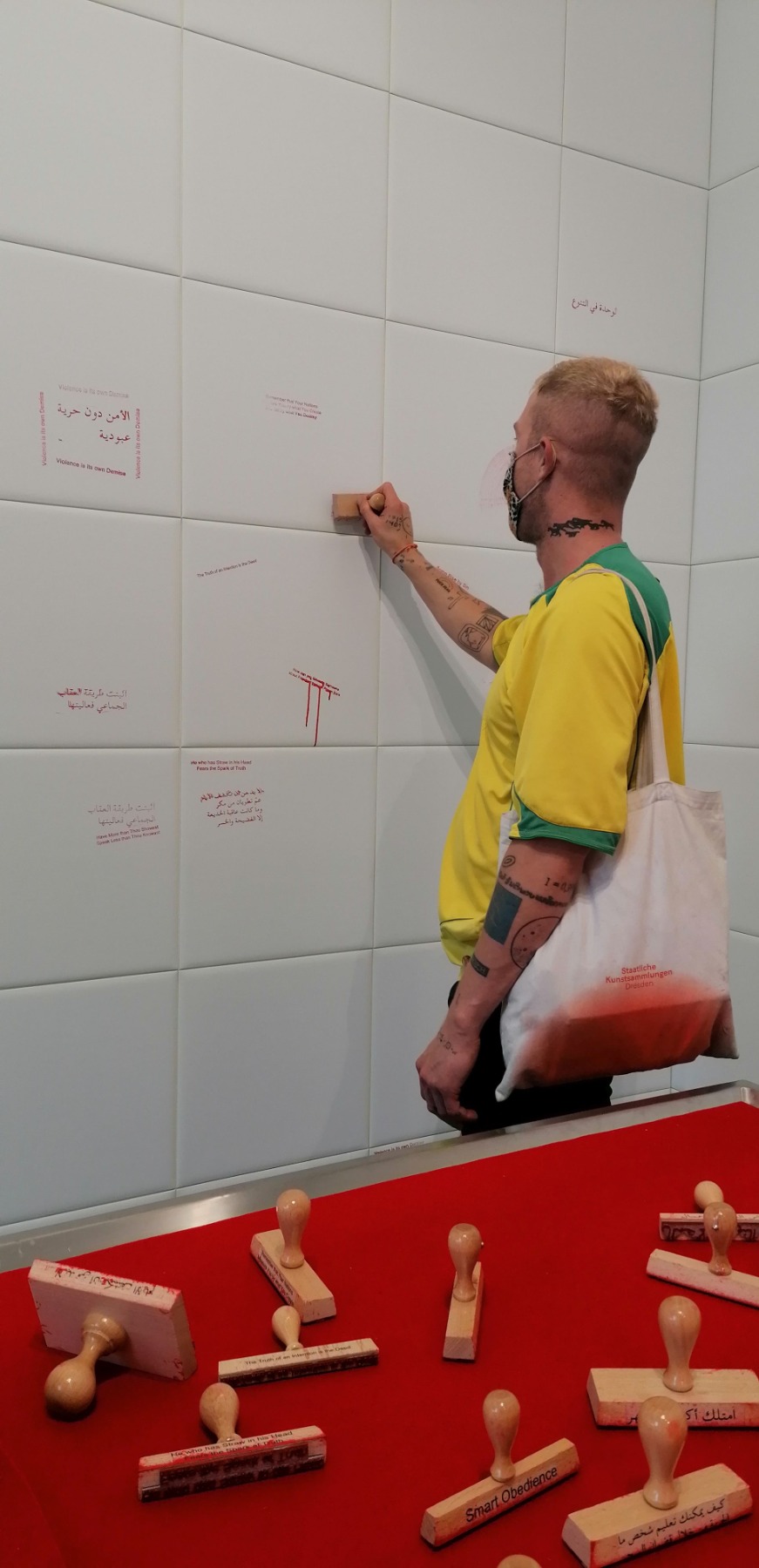

A visitor engaging with the installation The Safe (2019) at Galerie Nagel Draxler (Berlin, 2020) Photo: Elina Norden

Part of the installation The Safe (2019). Photo: Elina Norden

I insisted on doubling my time slot inside the installation.

No problem. Very smart, girl! (Laughs heartily)

I remind my students of their autonomy – independence in their own thoughts or actions. The freedom of thought is a human right, and a person’s free actions occur primarily in the mind and not in nature.

I'm also explaining to them the difference between free thinking and free expression. For our country, we need these emerging artists as free thinkers. I also warn them because we have seen a lot of talented people who expressed themselves freely on Twitter end up in prison. Why would you do that, really? Be smarter than that. Be realistic. You can pass your idea on through an artwork.

There are many artists and intellectuals who enjoy so very much the adrenaline of working against the government that it is as if they have forgotten their true talent. And we miss them as artists.

The freedom of thought is a human right, and a person’s free actions occur primarily in the mind and not in nature.

How do you manage to stay true to your artistic criticism without ‘pulling a tiger's whiskers’ and playing into the hands of the system?

Look at the title of my first solo exhibition in Berlin.

Smart Obedience.

I obey certain rules, however, most of my artwork is based on research.

Exhibition view Smart Obedience at Galerie Nagel Draxler (Berlin, 2020). Photo: Elina Norden

So, does that mean that the government can't deny facts?

Exactly. They can't find an excuse. If you read the poems and reversed phrases in my stamp paintings, they originate from the writings of various philosophers that I enjoy reading. What is there to oppose there? I'm not opposed to the government. I'm not even trying to convince anyone. I think that convincing someone is kind of an aggressive act. I want to do the right thing – to keep on looking from a humanitarian perspective that comes from many different angles, and to continue establishing a dialogue based on understanding.

The Stamp (Moujaz) (2017) © Abdulnasser Gharem / This enlarged stamp sculpture (made for Glasstress, a collateral event for the Venice Biennale sponsored by Fondazione Berengo) features the word ‘Moujaz’, which means ‘in accordance with Sharia law’.

Amen Stamp Print (2012) © Abdulnasser Gharem

How would you describe the primary art market and gallery scene in Saudi Arabia?

We have only one good contemporary art gallery – and a population of 33 million people. I'm very grateful to work with contemporary galleries abroad: galleries in Dubai, Gallery Nagel Draxler and Brigitte Schenk in Germany, Gallery Kinzinger in Austria. Oh my, Ursula Krinzinger is simply an amazing gallerist. Legendary!

Artists mostly sell works directly from their homes. When we started Edge of Arabia, there were young people following our activities. They became young collectors with us. They learn about the art we create, ‘contemporaneity’, and the art world ecosystem.

Another area for improvement is Saudi customs at the airport. We don't have a recognised contemporary art infrastructure as such. That complicates collecting art in Saudi Arabia. Oftentimes authorities won't even let a painting cross the Saudi border.

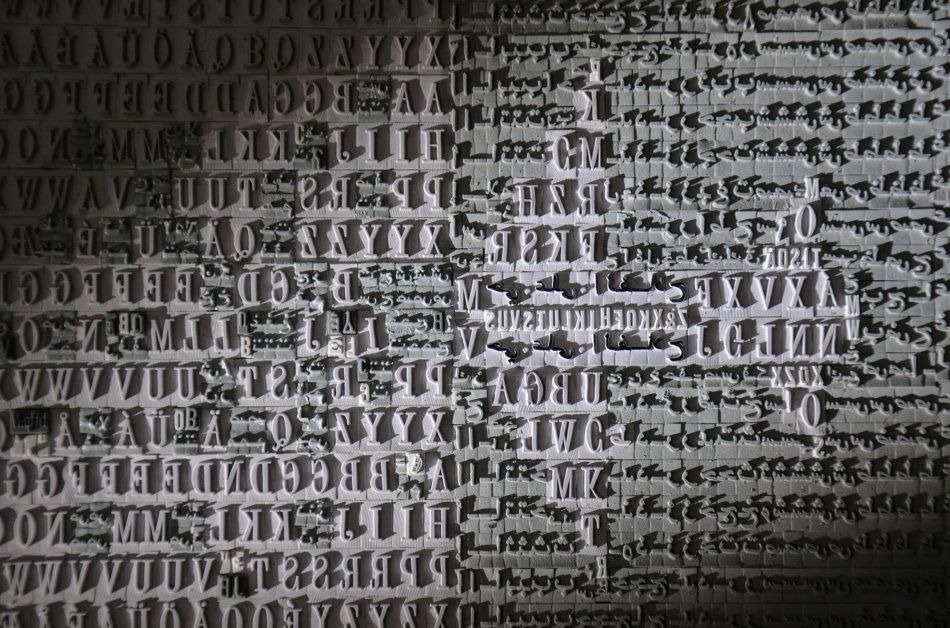

Detail from stamp paintings © Abdulnasser Gharem

(Detail) Prosperity Without Growth II (2020) © Abdulnasser Gharem / The artist’s fascination with stamps transfers to paintings and sculptures. In this case, the rubber stamps on aluminum provide the canvas for digital print and gold and coloured paint.

Pardon me?

Exactly. Unless you know someone who knows someone who can solve the problem. So, lately we’ve been trying to establish a dialogue with the authorities, such as the Ministry of Culture, to do something about these very basic things.

A good example is Sharjah in the United Arab Emirates. The city is similar to Riyadh. In 1993 the Sharjah Biennial was established. They had a lot of difficulties to overcome, but they gradually learned from the process. It became clear that if there is to be an art fair, paintings need to be allowed to pass through customs. Saudi Arabia needs the entire package: a supporting infrastructure, diverse art museums, an art biennial, local galleries, international art gallery branches, and an art fair.

In Transit II (2012) © Abdulnasser Gharem

Transitions are not easy, but it is so amazing to witness them taking place. Because the Saudi contemporary art scene is still in its infancy, you have a chance to mould it in a way that is right for the community. The Western model is not necessarily the ultimate one.

That's a very good point. We should not copy what's happening in cultural metropoles in the West. It simply isn't going work the same way here. In many Gulf States I’ve seen the authorities’ desire to stimulate a contemporary art scene by showing highly respected pieces from the West, but the general public here was simply baffled. For example, a public sculpture by Richard Serra was unveiled in the Qatari desert, and people asked: Who is Richard Serra and why is his sculpture in the desert? This is what I mean with prioritising and investing in education. Authorities should gradually introduce the public with this kind of art: what is land art, who is Richard Serra, his education and influences, and an artist's statement.

A public sculpture by Richard Serra was unveiled in the Qatari desert, and people asked: Who is Richard Serra and why is his sculpture in the desert?

Have you ever thought about stepping into the official cultural sector? Would you be a challenge for them?

I would not mind under one condition – they must let me do what I believe in. I am not against anyone, but I insist on mutual respect.

Honestly, I prefer working with nonprofit organisations and engaging directly with society without any economical interest on my part. This is more important for me than an official's seat with the highest salary. Honestly. I want to stay an artist rather than become a state employee. I want people to see me as Abdulansser, a Saudi who is just like them. I want them to think: If he can establish this space for free thinking by himself, we too can develop things. The mission of Gharem Studio is to build a new narrative for society. Here in the studio we come together as a collective, learn from each other, and think individually together. As an example, I was doing the budget for 2021 the other day and the students were with me, watching how to do this specific kind of paperwork. We talk about ethos, logos, and pathos, and how to be strong in self-governing.

Where is your art taking you now?

For some time now I've been doing research on how social media influences us. These platforms are important to me. But there are widely known alarming aspects of them. It is a temple of hatred. Twitter has become a place for organised aggression. Society is now eager to offer, on a daily basis, a new victim on the altar of social emotionality. If you want to find someone or something to hate without valid evidence, go on Twitter. Those who will engage in hatred will be the ones who know the least about the particular matter. Why do people hate? Because they are afraid of their future. This is so visible in the Arab world. There are social media armies, fake accounts in Saudi Arabia just for one purpose – to spread fabricated stories and to promote something wrong. And it takes over like a tsunami – thousands of retweets of fake news flooding the web with unimaginable consequences. There's no way to stop that from happening. I am currently working on this topic.

Twitter has become a place for organised aggression. Society is now eager to offer, on a daily basis, a new victim on the altar of social emotionality.

There is ‘good’, ‘bad’, and ‘in-between’ to be found on social media. Often I wonder if sharing news on political tensions is raising awareness, or actually encouraging more hatred among the communities involved. Just posting something is not activism – it is the most passive and non-heroic of acts.

That is a problem. You don't mean to do wrong – you share information because you care. Nevertheless, there will be people who will twist what you have said or reposted into something that is beyond recognition, and you will be in trouble. It concerns me what's going on on social media.

How can one become a successful cultural collaborator?

That’s an amazing question.

I'm focusing on blind spots in cultures. My focus is to bring into the foreground the issues that people don't want to see or, because of their position, they can't see. I want to reposition them and show this 'new area' that is part of their culture.

This is very important now in the whole Arab world. Saudi Arabia and the State of Israel are in talks to normalise relations. Domestically, there are disagreements between the conservative and liberal segments of society. State leaders can promote normalisation, but is society going to accept it? I wonder why people don’t or won’t. Is it just because they want to say ‘no’?

I'm focusing on blind spots in cultures. My focus is to bring into the foreground the issues that people don't want to see or, because of their position, they can't see.

As if by inertia.

It is definitely confusing to communities after such a long period of feuding. However, when I become confused about something, it is a sign that I must do proper research on it.

The philosophers Jürgen Habermas and Baruch Spinoza have influenced me. I believe in otherness, and I'm open to learn from others.

What is something in the Saudi world that Westerners should aspire to?

We have a lot of cultural resources in Saudi Arabia – archaeology, the history of Arabic languages, music, mythology. Our mythology has been banned in the educational system for at least the last fifty years because the radicals didn't want us to express it in art or music. Saudi Vision 2030 is now releasing what was locked away for a long time.

And it’s not just our arts – the people themselves are something to aspire to as well. Saudis are generous, warmhearted, and have a great set of values.

Society is transitioning, opening up to others, and we want to share our stories with others. We are becoming ‘normal’ again. Visitors are about to discover amazing facets of our culture and lifestyle of which they had no idea before.

Message Messenger (2011) © Abdulnasser Gharem / This ornate, golden dome-like sculpture is held up from one side like an animal trap, and inside there is a small dove. It is an artist's commentary on religion, which is beautiful but can also be used for ill.

(Detail) Message Messenger (2011) © Abdulnasser Gharem / This ornate, golden dome-like sculpture is held up from one side like an animal trap, and inside there is a small dove. It is an artist's commentary on religion, which is beautiful but can also be used for ill.

* Saudi Vision 2030 is a strategic framework to reduce Saudi Arabia's dependence on oil, diversify its economy, and develop public service sectors such as health, education, infrastructure, recreation, and tourism.

** Abdulnasser Gharem made his debut with The Safe (2019) in the UNLIMITED section of Art Basel in 2019. With this work, Gharem implicitly memorialises the murder of Jamal Khashoggi, who was a dissident Saudi journalist and Washington Post columnist. Gharem has recreated the oppressive atmosphere of an isolation cell as a space in which to think and contemplate the threats to media freedom that are ongoing worldwide. Visitors were invited to leave their ‘imprint’ with stamps on the padded wall, or to write a statement by hand. The stamps bear phrases such as ‘Smart obedience’, ‘Remember that your nations measure you by what you create and not by what you destroy’, and ‘The difference between the terrorist and the martyr is the media coverage’. – Ed. note.