Maria Kapajeva. If a subject does not let you go ‒ you have to do

Elnara Taidre

Maria Kapajeva’s exhibition ‘When the World Blows Up, I Hope To Go Down Dancing’ recently finished its run in Tallinn; starting from January 16 these works will be on view at the Finnish Museum of Photography.

Maria Kapajeva, a Narva-born Estonian artist, has spent 14 years in Great Britain. Since 2009 she has been teaching at the Department of Photography of University for the Creative Arts, Farnham. She has also held workshops and taught courses at other art colleges in Great Britain, Estonia, Russia, Germany, USA and India. Her solo exhibitions have been shown in Tallinn, Narva, Riga, Vilnius, Copenhagen, Białystok, Oakland and Bangladesh. Maria’s art is rooted in the practices of contemporary critical art ‒ an artist’s need to actively explore both the latest theories and the current social situation, including the conditions of disadvantaged groups in society. While Maria’s projects are based on serious research, their findings are presented using the language of art ‒ not as dry quasi-scientific conclusions but as intriguing visual narratives and captivating spectacles. Serious content is presented through creative interpretations, stories and metaphors, without force-feeding the viewer edifying lectures but offering emotions and food for thought instead.

Still from ‘Ten Ways Not to Become the Invisible Woman After 40’. 2020

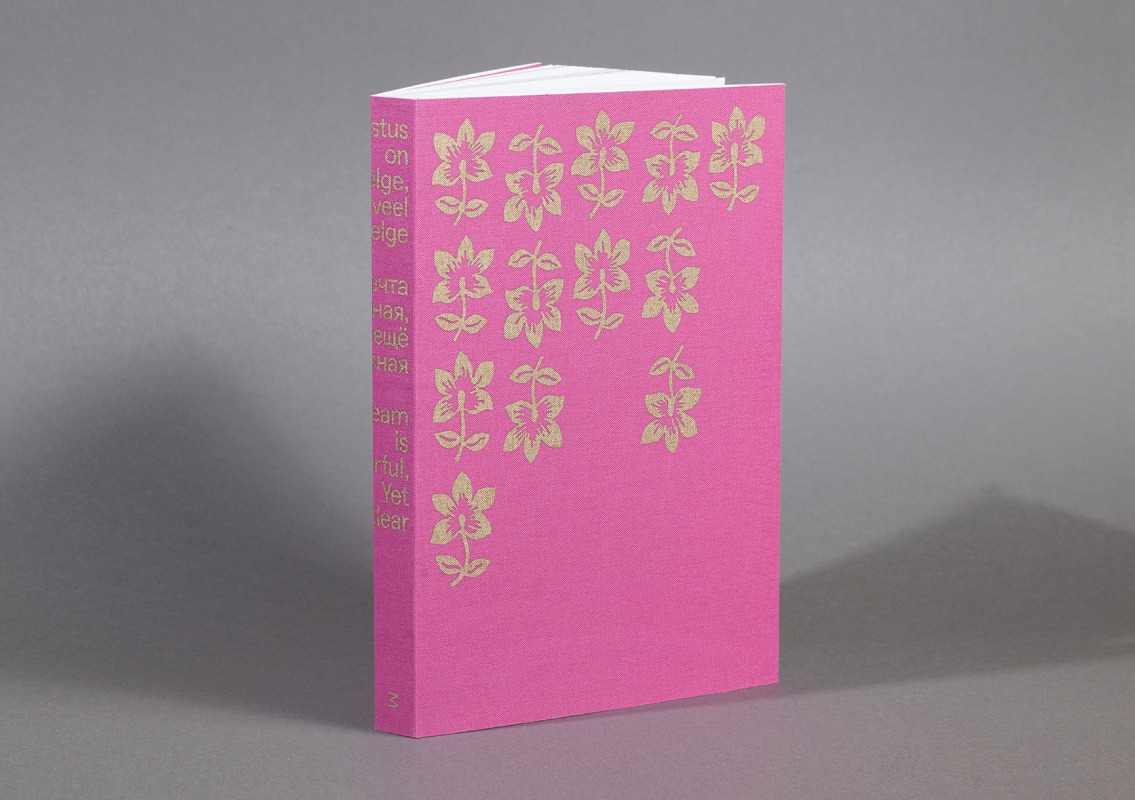

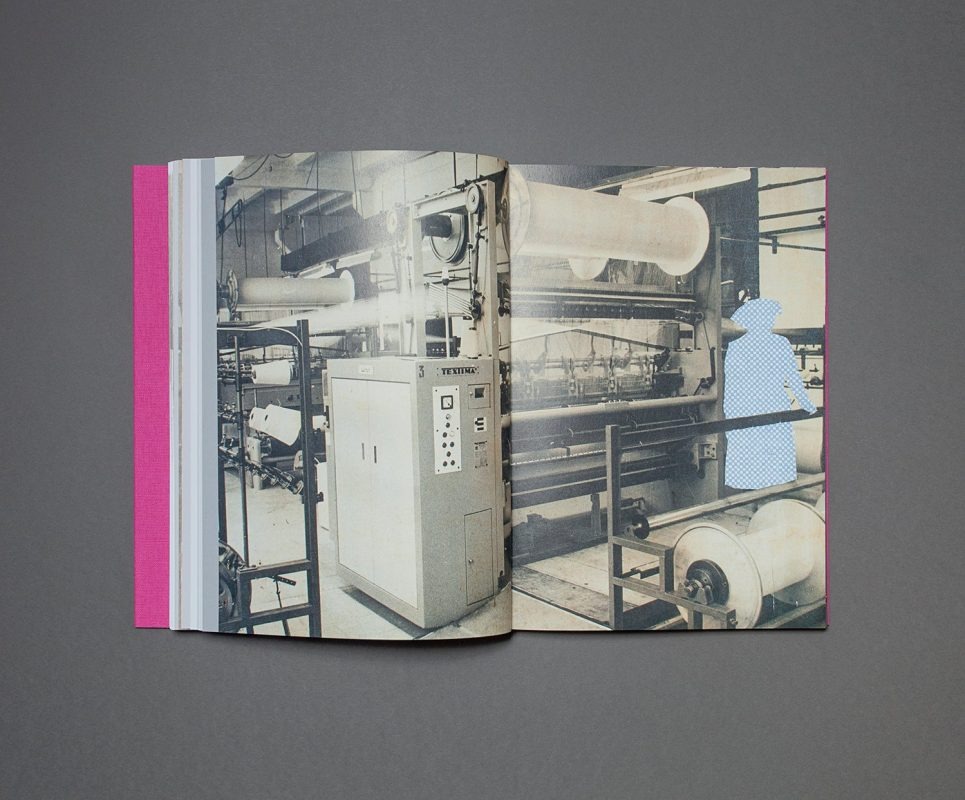

2020 was rich in developments for Maria: the artist moved back to her native Estonia; her book ‘Unistus on helge, veel ebaselge // Мечта прекрасная, ещё неясная // Dream is Wonderful, Yet Unclear’ was published by the Milda Books publishing house; her solo exhibition ‘When the World Blows Up, I Hope To Go Down Dancing’ ran at Tallinn Art Hall. In all of these projects, one of the most important lines in Maria’s art can easily be traced: study of the status of woman in a post-Soviet situation. It combines the personal dimension with an in-depth research of the issue in general. For instance, her book ‘Dream is Wonderful, Yet Unclear’ is a summary of an identically titled research project at an artist residency in Narva, dedicated to the local industrial giant, the Krenholm Manufacturing Company, its post-war history and closure following the collapse of the USSR, an event directly affecting Maria’s family. Her ‘When the World Blows Up…’ exhibition dealt with the situation of a forty-something woman focusing on self-realization ‒ with the pressure put on her by a society that still has not overcome its patriarchal ideas of woman’s role where family and children are always a priority. Using her personal experience as a point of departure, the artist creates generalized images and metaphors, revealing the context and scope of the problem. From 16 January 2021, these works will be on view in Helsinki, where the Finnish Museum of Photography is hosting Maria Kapajeva’s exhibition under the same title. We spoke about all these things ‒ without the help of Zoom or Skype, sitting across each other with an ordinary phone recorder between us.

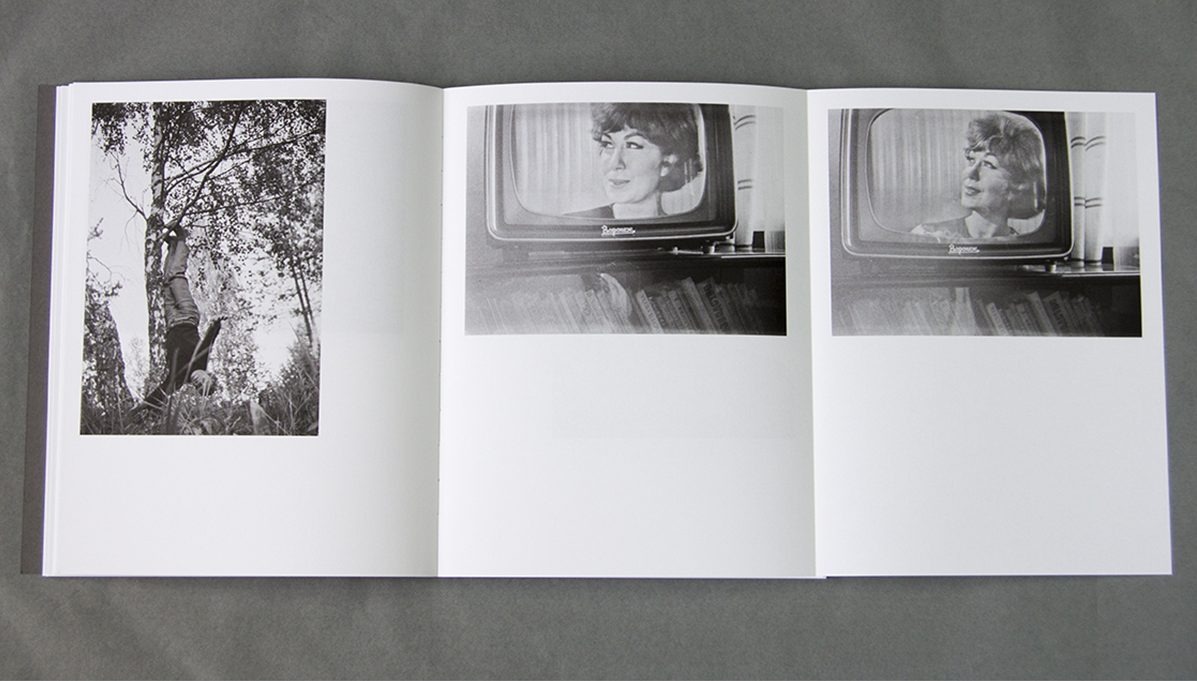

Book «Unistus on helge, veel ebaselge // Мечта прекрасная, ещё неясная // Dream is Wonderful, Yet Unclear». 2020

Let’s start with the big questions. What was your journey to an artist’s career? As a child, you had the example of your mother, a textile designer at the Krenholm Manufacturing Company, and yet after graduation you chose to study economics. How did it come about that you eventually went to study photography in the UK?

It started a lot earlier than that, when I was a teenager. At 14, I enrolled at an art school in Ivangorod (the Estonian city of Narva and the Russian Ivangorod constituted a single ecosystem during the Soviet times ‒ E.T.) where they taught a four-year programme. I lasted only two years there; Estonia then restored its independence and, as soon as I got my Estonian passport ‒ I was lucky to have the right to Estonian citizenship by birth ‒, it became impossible to continue my art education in Ivangorod. It was also then that I realized that I would not be able to study in Russia like my mum had. Meanwhile, the experience of Russophone students at the Estonian Academy of Arts was described in very gloomy terms at the time. And so, at the age of 16 or 17, I gave up the idea and spent the remaining school years torn by complete indecision regarding my further choices.

After some conversations with my class teacher, I decided to enrol at the Faculty of Economics: I was quite good at maths, and there seemed to be a certain humanitarian element involved in economics as well. The truth is, I did not enjoy it at all. Later, when I was already working in Tallinn, I took up photography. As a child, I used to take pictures of my friend on dad’s camera. Dad and I printed the photographs in the bathroom. It was all very much a sporadic thing, though. Whereas this time around, photography came into my life exactly at the right time: I got really involved, I realized that it was interesting. And so I decided to try and get accepted into a programme of this kind ‒ I had nothing to lose. Besides, this decision coincided with a desire to go and live somewhere abroad, a somewhat typical stage for young people from small countries. And so off I went and ended up spending 14 years in the UK.

How did you pick University for the Creative Arts, Farnham?

It was largely a random decision. I knew nothing about the leading art colleges in the UK; I simply chose among photography courses in London and its vicinity. There were three or four offers, and I picked Farnham. It may have been intuition or it may have been luck; whatever the case, I stayed there after graduation as a teacher, and I still teach there. As soon as I started my studies, I immediately felt that I was on the right lane ‒ this I found interesting. I had an opportunity to work in commercial photography, but I abandoned this thought very quickly.

How did it happen that you were asked to stay and teach there?

After I finished my BA degree, the Head of Department offered me the post of assistant lecturer. It was mostly administrative work but part of our agreement was that I would also gain some teaching experience. And so I spent three years working there, after which I joined the teaching staff. Furthermore, since 2013, I have been working with Professor Anna Fox on the research project Fast Forward: Women in Photography, based at the same university ‒ holding conferences, research workshops and mentoring programmes focusing on women in photography.

What were the subjects you were teaching?

I taught and I still teach practice. Despite the fact that I read a lot and am up to date on current theories, I am definitely not a theoretician. I don’t teach classes all the time; I work in the workshop format. I help students obtain practical skills ‒ how to take pictures, print photographs, make books. Or they develop their own ideas with my help ‒ they learn to realize their projects. It is not even directly linked to a specific medium: for instance, at the Estonian Academy of Arts there is not a single student from the Department of Photography on the course that I currently teach. It makes my work more demanding but it’s also more interesting ‒ observing how other people think and work, even on the level of a small idea.

You involve very different media in each of your projects. And so, I have a question about your art method ‒ how would you define it?

There is this term ‘research-based art practice’. It is probably what I do. I start off with an issue or a subject, and eventually the media emerge. Photography is always an inspiration, of course, but I must say that I am more inspired by existing photographs, be they old or new; I may have found them on the Internet or elsewhere. It is more of an exception than anything else that I made two self-portraits for my latest exhibition. I am currently very much interested in video, in the process of creating it. My approach is probably very photographer-like: I set up a static camera, and the video captures everything that takes place in front of it. Even things going on outside the frame. The result records, for instance, a performance. To me, it is an experiment, because I have no idea how the whole thing is going to evolve. Particularly when I work with other people, because it necessarily involves other individualities, other visions.

Found photographs and found objects ‒ it is an important layer of your work. And you worked with archives on the Krenholm project.

But found objects really are my archives; these things are equal to me. I often buy photographs at flea markets. They are not connected with a specific subject at the time; they are waiting for their time to come. It does not have to be a large collection; I may be inspired by something small. If a subject emerges that does not let me go, it means I have to do it. Now that’s my art method in a nutshell. (Laughs.)

You could probably say that your latest project are documentary, based on anthropological observations. Are there any fiction projects as well?

That is a big question ‒ what is documentary and what is fiction? That is exactly the most interesting thing about photography: what is true and what is false in it? If there is truth in it, how do you get to it? I think I am interested in an already existing document; I find it fascinating to explore it history and its current context. But if we think about my video ‘Ten Ways Not to Become the Invisible Woman After 40’ ‒ it is not a document; it is something made up and produced, although based on an already existing document. That’s probably why being an artist is so interesting ‒ visual language allows you to do anything. It may be absurd; it may be serious.

Fragment of the OR OTHER installation

By fiction I mean the visual arts’ equivalent of literary fiction ‒ a completely made-up story.

I did an in-depth study of this type of fiction in my video ‘The Bright Way’; I found it very interesting to have a go at these methods, to explore how cinema makes you believe that it is all true. My book on Krenholm includes a fragment of an interview about a future Krenholm worker believing in the singing-and-dancing-among-machines character played by Lyubov Orlova (a textile factory shock-worker in a 1940 film painting an idealistic picture of the Soviet industrial life ‒ E.T.). She must have realized that real life was not quite like that even before she came to Krenholm. And yet she did make her dream come true – all her life she was a dancer in a local amateur ensemble.

I find it intriguing how easily we operate with concepts like propaganda or stereotypes. And I try to make sense of them ‒ let’s try and find out what lies behind them. In our geopolitical context, propaganda is associated with the Soviet past. But we forget that we, too, live in an age of propaganda and that, to an extent, we tend to believe some of it, including advertising. I find it interesting to break down this language ‒ stereotypes regarding women’s appearance. The ideas of how a Soviet film character or real-life woman is or is not supposed to look after the age of 40. For the most part, I use visual language ‒ film, photographs, pictures.

Still, it is all human-centred?

I think people are in the centre of it all for all of us. Even if there is nothing directly involving a human body in a work, it will always still be about people. Because it I people who will be viewing it and thinking about it. I am interested and inspired first of all by stories ‒ by stories of people in (photographic) objects or reports. These are all very personal stories that have to do with a specific person. But if this story has moved me and stayed with me, I know that there is something more to it than just that.

Yes, I frequently say that my art is centred around woman, but that is largely to do with the need to explain my position as an artist in a so-called artist statement, in 50 words or so. I used to think that my book ‘You Can Call Him Another Man’ (2018, Kaunas Photography Gallery), based on photographs by my father as a young man, was always somehow apart from the rest of my work. But it made me reflect on what exactly a feminist approach was. And I realized that for me it meant telling some kind of alternative stories ‒ about things that were left outside the frame. Lending voice to someone who has been left outside. It can be very political. For instance, in my latest book ‘Dream Is Wonderful, yet Unclear’, I managed to record and give voice to at least a small part of the stories of Krenholm workers made redundant in the 1990s and 2000s, who had simply not been listened to at the time.

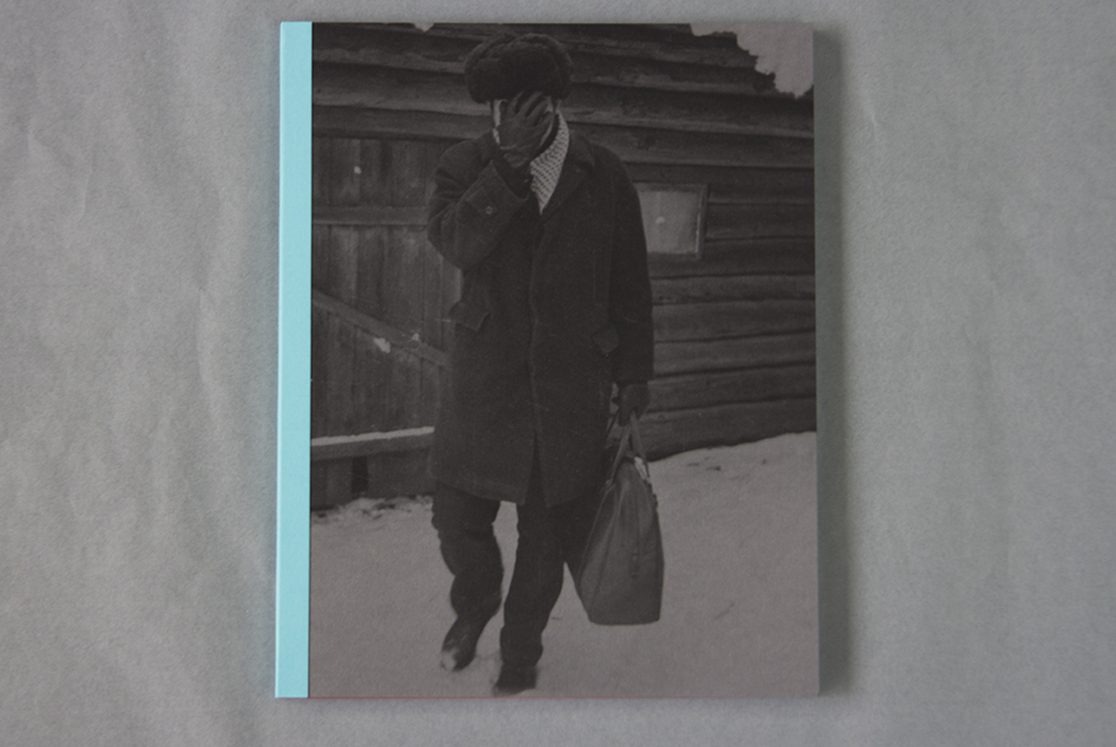

When I was working on ‘You Can Call Him Another Man’, it seemed to me initially that I necessarily had to include a political element, because the events dated from the late 1960s and early 1970s, when the world was in turmoil. But then I realized that it would have been a very artificial approach. For me, it is an alternative history of the Soviet era when politics manifests itself on the level of illegal pictures of The Beatles, the Moscow News newspaper. How did they get there? Where did my father find them? And yet it is a background more than anything else: when you are twenty, you want to go crazy with your friends, fall in love and listen to music. If I think about it, the book is actually about me; it was my first attempt to approach the geopolitical aspect of my identity. To look at who I was and where I was from through the lens of my father’s photographs. It seems to me that, the more I grow in my work, the closer I get to myself ‒ and nobody else.

Book «You Can Call Him Another Man»

‘You Can Call Him Another Man’ – it is not just a book but also a series of exhibitions.

I made the book during my FATHOM residency at the London Four Corners, a film and photography centre focusing on analogue photography and films. I knew from the very beginning that I was going to base a book on this material, but I also wanted to mount an exhibition. If I had simply taken these photographs and presented them as a photography show, it would be my father’s exhibition, not mine. I started thinking about things that I found interesting and eventually chose a solution similar to Italo Calvino’s novel ‘If on a Winter's Night a Traveller’, where each chapter starts a new story. And I decided that every time I would show this material ‒ my father’s photographs and Calvino’s text ‒ I would build a new narrative out of it. I also tried to form a dialogue with the specific space: for instance, on the staircase of a London art space I arranged the intallation so that the narrative would read one way if you were going upstairs and completely differently on your way back downstairs.

Until 2017, it was just a mock-up of a book; I was able to complete and publish it during my residency at the Kaunas Photography Gallery. It was also in Kaunas that I turned it into an interactive show where the visitors could construct their own narrative or exhibition out of copies of the pictures and Calvino’s text. Those who took part were free to do whatever they pleased with the material. It was very interesting to observe how different people work in different ways: somebody is simply looking at the pictures, somebody else goes with how they are feeling today, while others are assembling their own portraits. In 2018, the same gallery came up with the idea of ‘Narratives Alongside Him’, an exhibition built as a dialogue between father and daughter and curated by Gintarė Krasuckaitė; I contributed to it alongside three female artists from Lithuania and Latvia. I used TV sets, since Dad had many photographs featuring television. I picked pictures of a single on-screen figure, a male one; as a rule, these are all singers, actors, famous men. It was an interesting dialogue for me; I showed how Father, a young man at the time, looked at his heroes while I am now looking at him, searching for him through these images.

Continuing the subject of workshop ‒ could you tell us a bit more about your work as a teacher?

I am interested in practical stuff, in experiments with my students whom I consider fully fledged professionals. My task is simply to provide them with space and time to try out things while engaging in dialogue with me and the rest of the group. To me, it is crucial that people in this group communicate between themselves; the rest is optional. Of course, I can suggest working with various materials or media. But it’s always much more interesting to leave the structure of the workshop open to retain flexibility, ability to adjust to whatever these people find interesting, whatever works best for them. I have been teaching in a number of different countries ‒ in India, Russia, Germany, USA. Next year I am teaching a course at the docdocdoc school of contemporary photography in Russia; incidentally, the course will be centred around archives. Teaching is, of course, one of the few ways of earning a living for artists, but I also like it that there is a huge dose of enjoyment in it and a certain challenge that does not let you relax, because people constantly want something from you ‒ knowledge, skills, comments.

You have repeatedly mentioned artist residencies. Could you perhaps be described as a contemporary nomad artist travelling from residency to residency to realize your projects?

Actually, until now, all of my major works have been made at artist residencies. Not the actual research; I did that back in London. But to really get the projects off the ground, I needed the residencies. And, as a rule, I always managed to find these opportunities. What I liked about residencies was the fact that, by changing the environment, the distance from your everyday life increases really fast. Even if you have to keep working remotely, there is a completely different dynamic; also, it helps you make space in your mind for focusing on a specific part of your work. And, of course, there is physical space: I did not have a studio in London.

The main drawback of residencies is the fact that it is a very intense period when you have to accomplish a lot in a very short time. I still have some unfinished works that I started making during a residency but ran out of time and did not get them ready for an exhibition. Particularly if the project has to do with a specific location: when you go home, you lose this close connection with the context. Now, after moving back to Estonia, I am entering a completely new stage: I must learn to work staying put, in my own studio. To find a rhythm for working constantly instead of under pressure.

What has been the impact of coronavirus on your work? Residency opportunities have significantly decreased now. Your landlord cancelled your lease, and you were forced to move out.

Coronavirus has influenced both the way I think as an artist and the things I do, my rhythm of life. Many people probably find themselves in a similar situation these days. In my circle at least most artists are used to travel a lot ‒ for exhibitions, workshops, artist talks; and now these opportunities have all but disappeared. I have always been travelling a lot, and so the coronavirus situation has strongly highlighted the issue of locality for me: perhaps this is the time to stay in a place that is good for your work and that you interact with. London is wonderful, but when the city is in a lockdown and you don’t have any access to your friends, transport, exhibitions, theatre shows, all the things that people go there for ‒ you feel completely cut off. During the lockdown I had to move out of the flat I was renting in London, and that became the final straw that made me leave the country. Estonia was the most logical place to go to: I have always found support here; there was a summer exhibition in the works. It is not quite clear as yet how things are going to work out for me, but I absolutely feel right now that I have made the right decision. So far everything has been going much better than it would have been back in London under the same circumstances.

Is there any difference in how you saw the Estonian art scene from London and how you see it now, as an insider?

I would not like to generalize too much, but I am happy that art life in Estonia is very dynamic; there is a lot going on all the time. There is completely no sense of stagnation, not even due to the coronavirus pandemic. I would love to take a more active part in the whole thing.

Still from ‘Ten Ways Not to Become the Invisible Woman After 40’. 2020

While we are on the subject of location ‒ would you say that your Narva roots have influenced your art?

Yes, in everything. I suppose this sense of not belonging completely to any community, to any group, of always being the Other is never going to leave me. And becoming an artist was the most wonderful thing that could have happened to me in this situation: as I was accumulating knowledge of the visual language, I also started to make sense of it all. I found a way of dealing with the whole thing, including myself, of finding an outlet for my worries and concerns. The geopolitical situation, the frontier town, the different communities ‒ I suppose I will go on working with that; there is no escaping that.

What about your mum’s work in textile? Textile objects occasionally do appear on your projects.

I do not have an objective of working in textile, but it is part of my personal story. And when it happens, it is great. It is a comfortable material for me; all the processes are familiar and make sense.

Importantly, you choose your medium depending on the project, the story and the characters. But how did you end up making books?

At the time when I was graduating from by BA programme, there was a real photography book boom. Apparently, a rise in the quality of printing coincided with a decrease in the cost. They started paying attention to all the elements of a book ‒ design, quality of the photographs; photography book transformed into a work of art in its own right. A book provides an opportunity to show your art to a much wider public than the exhibition format. I made my first book in 2008, as a student. In 2009 I published three books under the title of ‘Three Books’, featuring found material. Until then, I had no idea how to show this material; this seemed like a very logical way of arranging things. It was probably at the time that I came to this understanding that book is a separate medium that works very well for some projects. As for my father’s photographs, it became immediately clear to me that this huge volume of material can only be shown in a book. It was then that I learnt to do everything myself ‒ the design, the binding, etc.

Book «Unistus on helge, veel ebaselge // Мечта прекрасная, ещё неясная // Dream is Wonderful, Yet Unclear». 2020

Tell us about your latest book.

In 2017, when I mounted an exhibition that was the result of a three-year project, there was a great amount of material that had to be left out due to lack of space. Nevertheless, it was also clear that it must somehow reach the public. And so I immediately thought of making a book. In late 2018 I met the graphic designer

Jaan Evart, and we both felt at once that we should collaborate on this project. Moreover, I had already realized that I wanted to work with a professional designer on my second book, someone whose knowledge and experience would help me create it. The value of the book lies, first of all, in the fact that it is trilingual (in Estonian, Russian and English) and therefore accessible to a large circle of readers. Second, it is available at the National Library of Estonia and every library of Northeastern Estonia where the city of Narva is located, and it also travels around the world where people read it. I am also immensely happy that I was able to give a copy to everybody who shared their stories and photographs with me, although there were so many pictures that it was impossible to include them all.

Still from ‘Ten Ways Not to Become the Invisible Woman After 40’. 2020

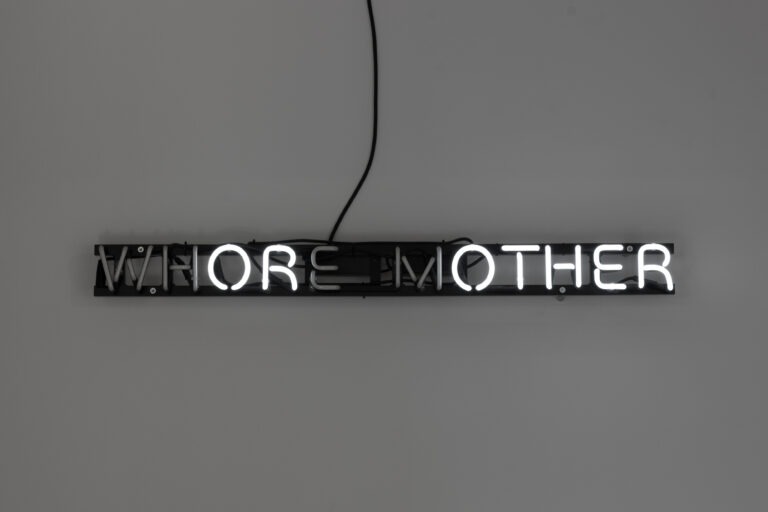

Perhaps you could tell us about your latest exhibition in a couple of words?

Returning to the subject of art residencies, a very important role here was played by the residency at Łaźnia Centre for Contemporary Art in Poland. They supported me greatly; the whole production work was done there. I left Poland in late February, and ten day later the whole world was shut down. That was incredible. I went back to London with a load of material which I had managed to complete there. Without that, the exhibition would have been impossible. The subject of middle age became significant for me at the relatively early age of 35, when I had ‘outgrown’ the somewhat indefinite status of a ‘young artist’. After 40, I started to notice that I was being treated differently by people around me: you are gradually slipping out of the circle of ‘beginners’ but have not as yet reached another stage; you are in transit.

40 years for a woman usually marks a kind of border; she has to make a decision about having or not having children. I discussed this a lot with people from my circle; I was having serious doubts whether we need this kind of exhibition, even more so in the middle of a global pandemic crisis when the problem of invisibility of women over 40 might seem somewhat insignificant. But thanks to the support of my friends and colleagues, I simply carried on doing what I had planned to do and saw it through to the format of an exhibition. Unexpectedly, the response was very strong; the show struck a chord with many people. And it is always very stimulating. I had some ideas that were left unrealized for the exhibition; perhaps I will go back to them. First I must understand if I have anything left unsaid on the subject; perhaps I have already expressed myself fully in this respect. If there is one thing that I find boring, it is repeating myself.

Top image: a fragment of the OR OTHER installation.