Humanity at the age of virtual transition

An interview with artist Mindaugas Gapševičius

After locating each other geographically – Miga was in Leipzig, Germany, whereas I was in Riga, Latvia – we started talking about how the pandemic has influenced our daily lives. Miga – or Mindaugas Gapševičius – is a master of being in-between places, “sometimes here, sometimes there,” referring to Berlin, Vilnius, Weimar, and Leipzig. And this in-betweenness extends even broader when both real and digital spaces are taken into account. Lithuanian by birth, Miga trained in oil painting and fine art conservation and restoration at the Vilnius Academy of Arts, moving on to exploring the connection between the arts and distributed computer systems at Goldsmith University in London, UK; now he is further pursuing his interest in hybrid systems at Bauhaus-Universität Weimar.

My mission was to pick Miga’s brain on all things AI. We ended up talking about the ever-presence of technology, the fears related to technology and the tools for combating these fears, and plans for saving humanity.

I feel that a lot has changed for me. Especially when it comes to traveling – there’s so much less of it. How do you feel?

Pfffff, not much has changed on my side. I travel a little bit less, of course. For example, in the spring I didn’t travel at all. But this is probably somehow specific in my case because I finished all my projects at the end of February, and I didn’t need to travel to Weimar anymore because of the pandemic. In the summer I started traveling again – I was going back and forth to Berlin, Vilnius and Jūrmala.

Yes, these days we travel less but connect with each other digitally. It’s important to be comfortable in this space, which is also a subject of your work.

It had become important already by the end of the 1990s, I guess, no? Or the 2000s? It was very important for people.

How so?

Because, you know, ordering things online had changed many things. So, you would book flights online, for example.

Well, I’m very much a dinosaur. I’m twenty-three and the world of technology is still something extremely baffling to me. For me, this period of interacting with people through technology is quite challenging and life-changing.

I think Florian Cramer said something along the lines of – the generation born in the 90s already lives in a hybrid space; they don’t know the world without the Internet. So life for this generation is completely different. They cannot imagine life without the Internet. No?

I guess I can (laughing). But a lot of people of my generation really can’t. And, well, yes, I am trying to catch up.

Yes, it depends, perhaps. It depends on where they’ve been raised. What kind of tools or toys they had.

Glass Vessels at the exhibition "Microorganisms&Their Hosts". Photo: Andrej Vasilenko

Yes, for sure. In your body of work, you deal with very complicated and serious things: the well-being of people, microorganisms, computers, AI. But it also seems like you’re having a lot of fun. Somehow it is extremely playful – as, for instance, in your exhibition “Microorganisms & Their Hosts.” Was that a conscious decision? That’s the impression I had – that you’re having fun.

It’s an impression (laughs). I was completely conscious of it, of course. Many things regarding aesthetics come from my studies. For example, I have been working a lot with the color white ever since I can remember, so the color white is pretty natural in my aesthetics.

But the aesthetics could also be different when it comes to electronics and things in the digital world. So, certain things are new, and certain things are unconscious, of course. Many things were already conscious years ago.

Audience tastes yoghurt at the exhibition "Microorganisms&Their Hosts". Photo: Andrej Vasilenko

Do you think that having fun is also important?

I think it is important for humanity. I don’t think too much about myself playing, but I was developing many concepts from this perspective as well. It’s true.

Because the subjects that you deal with – science, microorganisms, the body – can be seen as intimidating or boring. You show that they can be fun, too.

Yeah, they could be fun, too. But in “Microorganisms & Their Hosts”, it was not that much about fun, I guess (laughs). In most cases it was very logical decisions that were being made in-between.

"Microorganisms&Their Hosts", Atletika gallery, 2020. Photo: Andrej Vasilenko

How so?

There are many things.

The complete microbiome, which thrives in our guts, interacts with us and makes an impact on our thinking, our behavior, and our feelings. So, for example, if you are sweating, you feel uncomfortable. If there weren’t any microorganisms, you would not be able to feel uncomfortable. The smell which arises is produced by the microorganisms – because they are proliferating. Same with the digestive system. If you eat certain products, you are able to feed your microbiome, which is inside of your guts; the microbiome, in turn, affects your thinking as well because of the vagus nerve connecting the guts and the brain. If you feel well, you can also think comfortably. And that’s how I came to the idea of the impact on our thinking due to collaboration with the microbiome. Some people are still skeptical of the idea of collaboration between humans and the microbiome.

Rectal Candle at the exhibition "Microorganisms&Their Hosts". Photo: Andrej Vasilenko

Yes, it makes total sense – what you eat impacts your microbiome, and then the microbiome impacts you. That’s really cool.

Shifting gears, what’s your relationship with fear? When do you feel afraid?

That’s a very good question and a very interesting and personal one because I dealt with this recently. I was always afraid of larger audiences containing people whom I do not know. Let’s say you go to a conference, and there are twenty people sitting in front of you, listening to what you say. So that was, for me, my biggest fear. I started to work with it, and I think I feel much less fear now.

By confronting it?

Not only by confronting it but also by thinking logically. It’s all about the things happening in the brain. And logic is important, definitely. It’s about how you see the world and how you perceive the world. Because all you do in the world is a reflection of what you see. But if you start to think that this is nonsense, you will, most likely, start to see the audience differently. And then something changes in your brain and somehow, you’re no longer afraid of it. It’s all about different constructions in the brain, I think.

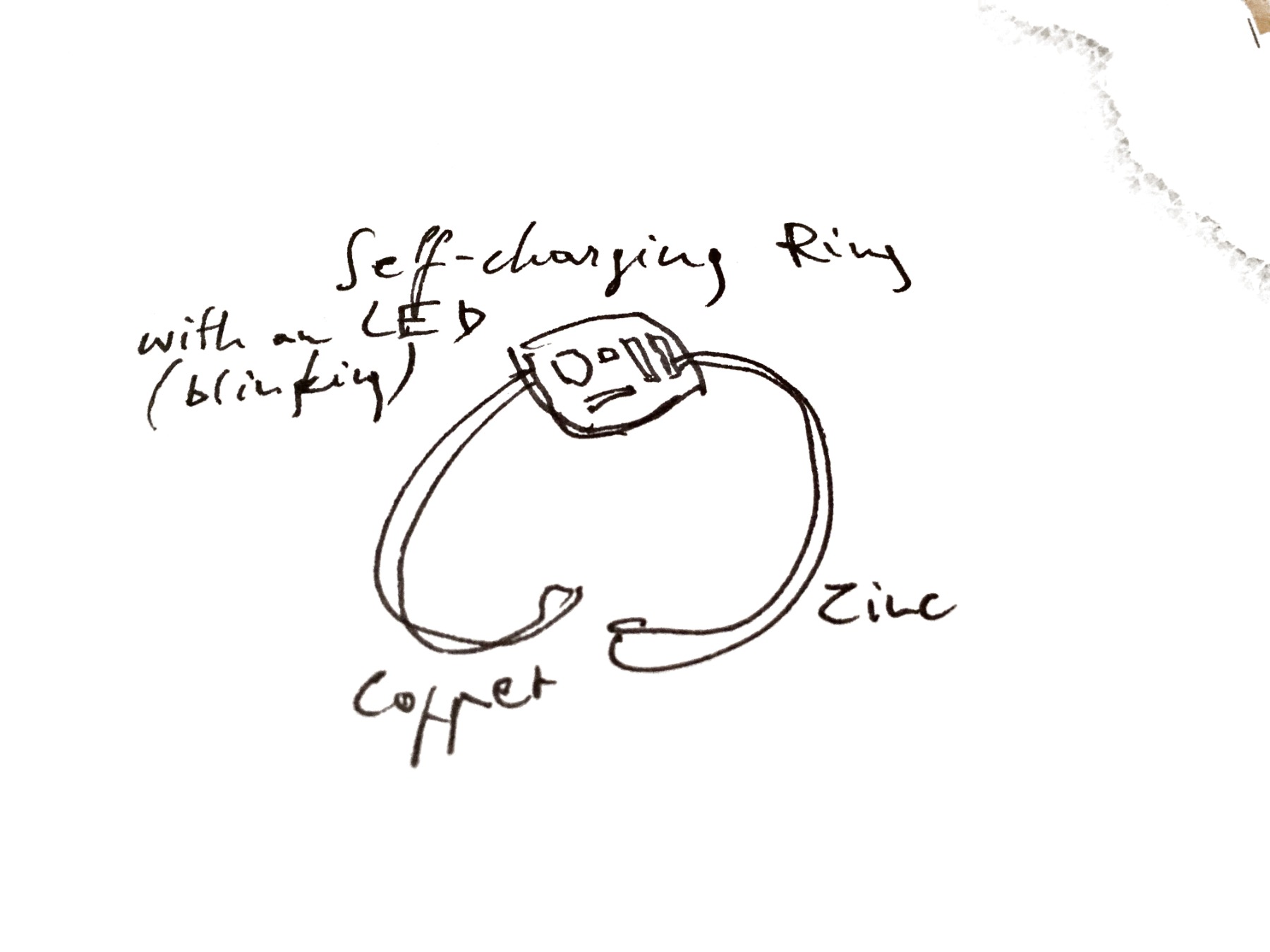

Self Charging-Ring, sketch Mindaugas Gapševičius

For sure. I asked this question because it seems that oftentimes when we perceive our body as a place for other organisms – such as bacteria – to live in, this may cause fear in some people. To know that your body is not just your body that belongs to you, but that there is also something there that you have no control over. This realization could cause fear in some.

It could. I’m pretty much comfortable with it. But yes, it’s a pretty recent concept, bacteria living together with people.

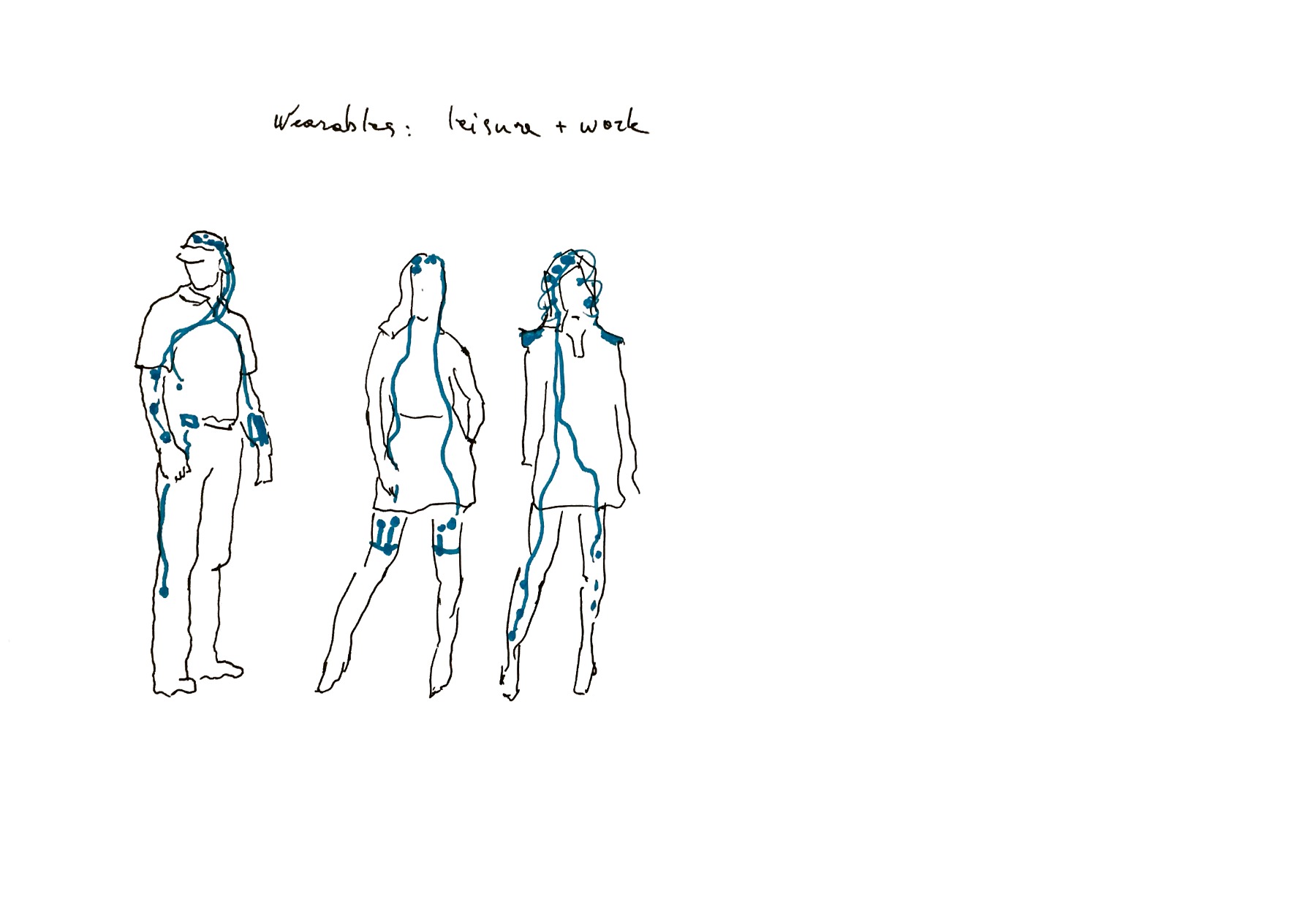

Humans in Wearables, sketch Mindaugas Gapševičius

Yes, this is a kind of collaboration between bacteria and humans. Which brings me to another part of your work: humans and “wearables” – devices that have the capacity to impact our nervous system. This is again an idea in which the human body is something that can be easily influenced. How did this idea come to you?

It is a long story. It’s not like you wake up in the morning and you’ve come up with something completely new and you immediately start working on it. I was working quite a bit with computers; I thought that technologies are cool and that we are heading towards an intelligence which we are calling “artificial”. But at some point you realize – no, no, no – it’s not happening that fast. In between, there is always this kind of a “bridging environment”. Let’s say, from organism to machine. Something is in-between all the time. You can’t be a human today and a machine tomorrow. Perhaps in the in-between there is always this hybrid state: machine and human. So this moved me a little bit forward towards thinking about life and organization within organisms.

Another thing was related to my previous research at Goldsmiths. I was working with distributed systems and reading scientific papers when I came across the German sociologist Helmut Dubiel. In 2006 he wrote a book about his life while having Parkinson’s disease. With this disease, you can’t really control your body any longer – your hands shake, your head shakes, or your whole body shakes, so much so that you can’t even be comfortable within your body. But he had a pacemaker inserted to control electricity being passed through electrodes into his brain. This would stop his shaking, for example. While he was in a comfortable state, he was able to continue teaching and living, and being really social.

This made me think quite a lot about electric signals being passed to the brain and being able to impact one’s physical condition. After some more research, I tracked down experiments being done with chimpanzees and sensors that would affect the brain in real time, independently from conscious control of the pacemaker. If you can impact your brain’s functionality by simply being in a different environment, then the environment could also affect your feelings, your thinking, and other things. In the mentioned cases it was, of course an electrode directly attached to the brain. But there are also different electromagnetic therapies that do not require an electrode attached to the brain.

Ultra Low Voltage Survival Kit, Introduction to Posthuman Aesthetics, Photo: Brigita Kasperaitė

Yes, for passing electricity through the body.

Yes, like, you know, you can stick electrodes around your head and you may get some function from it without too much resistivity. Electricity can be passed through the body without having an electrode attached directly to the brain. Passing electricity through the brain can help heal some diseases – depression, or schizophrenia, for example. So, if you are able to heal people in such a way, it leads you to think – why couldn’t wearables be about that? This is how we come to a point where we don’t necessarily need to be robots, but technology could impact our physical functions or emotions.

Cool. What did you try?

Well, I tried thinking (laughs).

So, in this project you’re not aiming to create actual wearables, but are just ruminating on what they could be like?

I haven’t experimented on myself yet. But with students we have been experimenting with passing electricity through our bodies. In some cases it perhaps wouldn’t impact one’s health, or it wouldn’t even be felt. But if you increase the current a little bit, you are able to feel the electricity – it’s a very unpleasant feeling. If one starts using it as a therapy, it could impact one’s body.

Introduction to Posthuman Aesthetics, MO Museum, 2019, Photo: Brigita Kasperaitė

It’s quite hard to get permission to work with human subjects.

Well, some people definitely do experiment. You can search on YouTube for something like “micro-voltage stimulation” or “brain stimulation”. I believe you will find nerds doing that, teenagers doing things like that.

I see.

It’s not yet artificial intelligence; it’s more about an additional impact. Elon Musk, for instance, is buying companies that dealing with the neurosciences, so one would think that someone is already working on this. They attach electrodes to the brain and try to play with digital information by converting it to an electric signal which, when passed to the brain, affects it, of course.

Yes, this is incredibly advanced stuff. Just like our brains process the information coming from our eyes, there’s already software that can “see” what our eyes are seeing. For instance, there are experiments in which people are shown images on a screen and there’s this device that can read the brain signals, the electric impulses, and converts them into an image. You can see what someone else is seeing.

Yeah, there are different techniques. So, there’s fMRI, for example, or EEG – it’s all about reading, or translating, electromagnetic waves into images. So, depending on the cortex being activated, you can understand or imagine what’s happening in the head.

How did you come to have a background in the cognitive sciences? Was that just pure curiosity and excitement?

I guess so (laughs). I was studying painting, then I learned programming and I did network administration, and then I learned biology. It’s all about curiosity.

But it also seems like you’ve found the people, the scientists, to collaborate with.

Yes; if you have an idea, you look for people who might help you. It’s not so easy to find scientists to collaborate with, or programmers, or whomever. But the first thing to start with is to learn things yourself. And at some point, reach a level at which you are able to speak the same language with professionals in biology, or programming, or other different fields. Otherwise there is miscommunication between people from different fields – like between an artist and a scientist. There is no chance of having a real discussion if you don’t have an understanding of each other’s needs and possibilities.

Well, maybe AI is going to help us with that kind of communication?

Yes, this is definite. I remember also being at a conference, Pixelache, in 2016 or so. It was about empathy, about understanding different organisms. At that time I was thinking of an interface that would work in-between humans and organisms – it would be able to translate certain things. For example, you’re going down the street and you see a dog barking. You aren’t able to understand what the barking is about. But if you own a dog, you might be able to guess about difference in barking – if the dog barks one way or another way, it means different things. These are pretty simple communications, so it should be possible to create an interface which would translate human speech into barking and barking into human speech.

(Laughs) That’s amazing. This is completely in opposition to the idea that machines are something that can destroy us – often in dystopian narratives, that’s exactly what happens. Machines rise up and destroy humanity. But as we can see from your example, they can also help.

Yeah, it always depends. I don’t think they will destroy us; I would rather be neutral on this. It’s always about humanity in this case, and humans are the ones who develop machines. Machines try to imitate humans, but they don’t create new humans. And this is why there’s no need to be afraid of machines.

For you, what is AI for? Is there a clear purpose?

It is for helping humanity understand nature. It is about generating capital. It is also about helping humanity. If it wouldn’t be for technology, we wouldn’t be able to speak right now, and we wouldn’t be able to share our ideas. Technology helps humans exchange ideas and develop something on top of it all. We want to understand the universe, therefore we develop machines that help us understand the universe.

If you had the help of any scientist in the world, and you could create anything – any kind of AI – what would you do?

I would make a copy of myself.

Why?

It’s interesting what would come out of that. The idea is to have two identical machines. So how would communication happen? On the one hand, there’s no need to have communication because you are exactly the same copy. And on the other hand, perhaps it could be something similar to accelerating your thoughts, because you need help to make certain decisions faster.

How is that different from being an identical twin?

Because twins are different. It’s not just visual. There are also physical differences. There are no two people who are completely, exactly identical. Imagine if you make a clone of yourself. It’s a copy of you, a clone of you, but it’s different from you because the environment where the clone is grown is different. Imagine the two of you, or twins, being next to each other. The environment still differs, even if you are placed in the same room, because of the diversity of air flows, air pressure, and so on. Identical twins are never completely, exactly identical. Never.

That’s why identical twins are often used in experiments that explore the impact of the environment. But an exact copy of you would also experience the same bodily changes that your body undergoes, right?

Yes. It would be interesting because it would be an identical copy. I would like to try it out.

Who knows, maybe one day...? Well, then that wouldn’t be a human, would it? But it wouldn’t be a machine either...?

It could be a hybrid. It could be neither machine nor human. To make an identical copy of you, you have to have sensors that capture information about everything going on in your body, and this information has to be sent to your copy, which then sends the information back to your body. A kind of technological hybrid.

And when not a copy of yourself, what else do you dream of?

Of humanity. I had a conversation with a friend of mine, Yuk Hui, a philosopher, some five years ago. He was about to publish a book. I don’t remember exactly what is was about, but he was talking about saving humanity.

What does this mean?

It means that we think too much of machines. Referring back to what you said before, we could develop machines to the point of a dystopia, or a utopia, emerging. Machines take over humanity. Let’s say it’s a possibility. Machines begin developing machines themselves. If this is the case, you start to think – what is your purpose in this world? You would probably try to continue taking care of your species, just like other organisms continue taking care of their species. Dogs would think of other dogs, humans would think of other humans, machines would think of other machines. So Yuk’s answer is pretty logical: the goal is to save humanity, so that it doesn’t disappear. To have diversity, which includes a species called Homo Sapiens.

So your dream is to save humanity?

I’m not sure; I was not dreaming so far into the future. But Yuk is a philosopher, and I think he’s right: he works in order to save humanity; otherwise it makes no sense for him to be here.

Does it make sense for you to be here?

Yes, of course. Otherwise I would not be thinking of art and ideas. Of course, I want to express myself and tell people something that I understand. And, therefore, it makes sense for me to be around here.

If you had to come up with one message that you could deliver through your work, what would it be? The most important one.

Well, for me, the most important one is that there’s no way back to ancient times; we’re living with machines, so we have to deal with them. How to tell people that we need to take care of machines, and to have machines take care of us, and how to develop this kind of communication, or collaboration. I think these are the most important moments I try to deal with.

That’s great. That’s very needed. Again, coming back to the question of fear, and the fear that mostly comes from not knowing. If there are people like you who can mediate these ideas, that’s a very important mission.

Right. Fear comes from not knowing about things. Coming back to my fear of having an audience – 20 or 100 people whom you don’t know – but as soon as you get to know them, you lose the sense of fear. Fear is always about not knowing something.

For me, it would be scarier to be in front of people that I do know.

(Laughs) Well, right now I am thinking of people – communities, society; they need to exchange the things that they do know in order to help each other, to make things happen. Because if you’re alone, you can’t do much. Therefore, you need to have a community and be able to communicate. There shouldn’t be any fear of being in front of the community, because what you need to do is understand other people, and other people need to understand you. Perhaps some kind of technological tool could be helpful here.

That’s such a nice way of thinking about it. Thank you for sharing it with me.

Title image: Mindaugas Gapševičius. Photo: Paulius Žižliauskas