We are all connected

An interview with artist Patricia Piccinini

The Instruments of Life, on show at the Kai Art Centre in Tallinn until April 25, is Australian-based artist Patricia Piccinini’s first solo exhibition not only in Estonia but in the entire Baltic region.

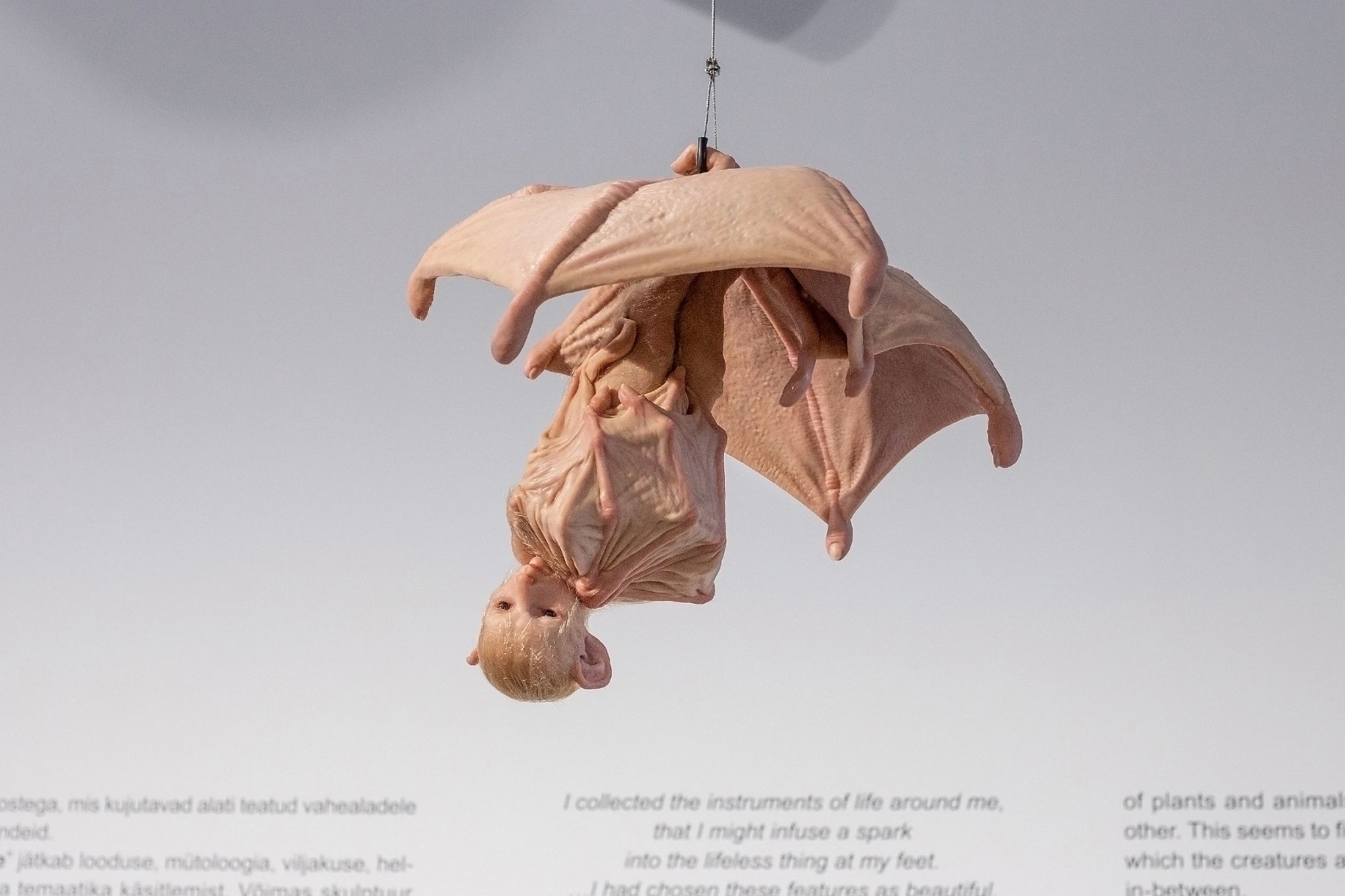

Piccinini is known for her hyperrealistic sculptures of chimeras – grotesque, surreal and sometimes quite eerie beings that nevertheless exude humanity and look like they could just as well inhabit a lucid dream as be the result of a scientific experiment in a laboratory. With her beings, the boundary between reality and fiction is further dispelled by the fact that they all have human eyes. Eyes that are disarmingly real, open, emotionally prodding, thoughtful and questioning. Eyes that embody the entire range of human emotion and feelings, thus confronting the viewer with fundamental questions about existence, both in the absolutely private sense of the individual and in the sense of humankind’s role, place and responsibility in the planetary ecosystem.

Yes, humans are capable of manipulation and do manipulate. They manipulate themselves as well as nature, but – as the current global pandemic has shown – they are unable to control nature or the course of evolution. What are the boundaries and consequences of human permissiveness? How ethical are biotechnology experiments? How inclusive and empathetic are we in relation to the other, to the foreign? How often do we think about the other people, animals, plants, birds and other things that share this planet with us? How often do we think about how they feel, or what it feels like to be them?

Piccinini’s work urges us to see beauty in all forms of existence, no matter how deformed or artificial they may sometimes be. She is also inspired by themes of fecundity in the broadest sense – the potential of life, empathy and the connection between species. At the same time, her beings remind us how genetically close humans are to other species, how greatly we depend on one another and the responsibility we have for everything we create.

Piccinini was born in 1965 in Freetown, Sierra Leone, in West Africa. In 1972 her family moved to Australia, where Piccinini grew up. Today she lives and works in Melbourne. She holds a bachelor’s degree in economics from the Australian National University in Canberra and a bachelor’s degree in visual arts from the Victorian College of the Arts in Melbourne, where she has been a professor since 2017. Her exhibition We Are Family represented Australia at the 50th Venice Biennale in 2003.

At the beginning of her career, Piccinini spent lots of time in medical museums studying and sketching the objects exhibited there. Still today, she begins each of her works with a sketch, which she and her team then later turn into a three-dimensional object. Each of the sculptures takes approximately one year to complete, and in order to achieve a hyperrealistic look, she uses silicone, fibreglass and human hair in the process.

Patricia Piccinini. Instruments of Life. Exhibition view, 2021. Photo: Mari Volens

Piccinini’s solo exhibition The Instruments of Life at the Kai Art Centre includes sculptures created between 2005 and 2020 as well as her new video work titled The Awakening (2020), which is dedicated to the body as a site of production, exploring themes such as rebirth and renewal.

Our conversation took place on Zoom, a few days after her gigantic, thirty-metre-high sculptures named Skywhale and Skywhalepapa (who is filled with 4.5 tonnes of air and holds the couple’s nine children in his arms) were presented to an audience of about 2000 spectators across from the National Gallery of Australia. “It’s about how we see a strong masculine figure nurturing his children and how beautiful that looks and the idea that care is not gendered; it’s not just female. It’s available to all of us,” comments Piccinini.

But seeing as there was no wind that morning, the Skywhales were unable to take their planned flight over Canberra. “So the balloons didn’t fly, but we did inflate them. And this meant that the people had to actually stay with them. They had the chance to really look at them, because they didn’t fly away. And in the end, people said it was actually OK that the balloons didn’t fly, because we had to stay with them. We learned that you can’t control nature, you can’t tell nature what to do. We want the balloons to fly, but it’s up to nature to decide,” Piccinini says later in our conversation.

The eyes are very special in your sculptures. And your hybrid creatures, or chimeras, have human eyes. What do eyes mean for you as a symbol? How do you make them? And how do you make the eyes of your creatures so alive, so human? It seems that you’ve put a lot of thought into them.

I make artwork for humans, so the eyes are vital. We’re one of the few species that have whites around our eyes, and this helps us to “read” each other better. We tend to understand the way we’re related through the eyes and eye contact. As humans, we tend to understand the world predominantly through visual means. If I made artwork for dogs, I wouldn’t be making works where eyes are really important, because dogs understand the world through smell. They don’t really care that much about eyes. They understand what you’ve done, who you are, your place in the world, your history and so on all by how you smell.

A lot of my work in sculpture deals with the morphology of the body, how the body is placed. In large part this is what determines how viewers will perceive the work. If the eyes are downcast, if they’re looking straight at the viewer, or if they’re confronting our inner world – these things are all very legible to us.

The eyes in my work are mostly very human, which creates a connection between us and the creatures both emotionally and genetically. However, there have to be subtle differences. In Kindred (2018), the mother’s eyes are actually quite orange. We tried to use dark eyes, but they didn’t look right. It took quite a while to work on them. They look pretty natural, but they’re actually really orange, and they fit the face beautifully. The eyes create a subconscious aspect of our communication that we’re not really aware of, but it’s there.

My studio makes all the eyes for the sculptures. When I first started making this kind of work, I worked with a man who makes prosthetic eyes for medical purposes. However, he was very hard to work with, because he wouldn’t ever change the eyes. If I needed them bigger or smaller or a different colour, he always said no. It made me realise that we had to make them ourselves in the studio. It’s taken us quite a few years to develop the process. They’re all hand-painted, in acrylic and resin, with a depression for the iris and the lens on top, which means they’re not completely spherical.

Patricia Piccinini. The Loafers, 2018. Courtesy of the Artist

Your Shoeform sculptures of plants growing out of stiletto heels (some of which are featured in your exhibition in Tallinn) are surrealistically beautiful. On the one hand, they make us think about the beauty of plants and the beauty of the connection between plant forms. On the other hand, they remind us that nature will survive, it will recover, it will take over, but we as a species are the ones who might become extinct after what we’ve done to nature, and we urgently have to take steps to re-establish our lost partnership with nature. What is the story of the Shoeform sculptures, how was the idea born? Maybe you have a completely different interpretation?

Certainly my ideas are related to how you see it. My work is a lot about the boundaries between things, the boundaries between us and other species, or technology and nature. Much like the figurative sculptures, the Shoeforms are chimeras, except more extreme. Shoeforms are chimeras of the organic and the manufactured.

What I’m really interested in with those works is the idea of how we categorise the world and how we impose these fairly arbitrary boundaries around themselves, and between ourselves and others. With Shoeforms, I’m imagining something, a metaphor really, that collapses these boundaries. I’m interested in this because, when you create a boundary, like saying “Oh, this is natural, and this is artificial,” then you’re creating a disconnection between us and the world. But that isn’t working anymore, because we only care about the “us” side of the boundary.

Patricia Piccinini. Shoeform (Tresses), 2019. Photo: Mari Volens

And this brings me to your comment about the survival of nature. Will it recover? Will it take over after we’re gone? All of this presupposes a disconnection between “us” and “nature”. This is a problem of putting ourselves on one side of the boundary. Are humans not part of nature? Are we not natural? Why do we do this?

For example, the notion of “black” people is actually relatively new. White people created this distinction so that we could distance ourselves from black people, as a justification for slavery. Or take the notion of women. I mean, we are different, but the idea that we are another category of being? Patriarchy creates this category in order to control women, our sexuality, our reproductive capacities. I see these boundaries as very dangerous.

These categories are pretty arbitrary, and by definition and design they only serve some people in our society. The “nature/culture” distinction serves to remove humans from nature so we can control it. We distance ourselves from nature; we say we’re technological, and therefore we can exploit nature and use it as a resource. The fact that we don’t feel connected to nature allows us to treat it the way we do, which is terrible. We burn down forests, we take away the environments of other animals. Because we’ve lost, or suppressed, this sense of our connection with nature, it’s really difficult for us to understand nature.

When creating Sapling, you were reading Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge and the Teachings of Plants by Robin Wall Kimmerer. Sapling is about the relationship between a human and a plant-like chimera. Do you think it’s possible for a human to understand what it’s like to be a plant?

I don’t think we can actually experience what it’s like to be a plant. But I think that through the work of people like Kimmerer, and with the help of indigenous knowledge, we can now re-evaluate how we understand plants. Just because we can’t understand what it means to be a plant doesn’t mean we shouldn’t value it. Kimmerer struggled very much with how plants are categorised. She even came out and said, “Hey, that’s not actually how they work. They have relationships, and they’ve evolved to do certain things, because they’re co-dependent. They’re not individuals.” All sorts of other knowledges have sprung up from those beginnings.

We may never know how plants physically embody that sensation of self, but that doesn’t mean they don’t count. The idea of “personhood” for plants comes from the legal ideas that non-human actors, such as companies, are granted the status of a “legal person”. So, if people can only value people, then we need to give similar personhood to plants to provide them with equivalent legal protection. This is seen as a way to protect them from environmental violence, because if you say they have personhood, then they have rights. And that’s great, if it works. But plants are not people; they don’t want or need the same things as us. They want other things. But what are those other things? Can we figure out what they are? Surely they don’t need to be people to have rights, so what are the rights of a plant? And how can we give those rights to them so that we can ensure they’re able to thrive?

Patricia Piccinini. Cleaner, 2019. Courtesy of the Artist

Your works make one think a lot about the troubling developments related to the advance of biotechnology and genetic manipulation. If you look at medical innovation, it has fantastic potential to make lives better, to save lives. But at the same time, Big Pharma is a huge industry interested in profit. When working on Kindred, you were reading Mary Shelley. She was an abolitionist, and because of that she didn’t eat sugar. As you said, we treat nature and other species as badly as we do because we can’t step into their shoes. In our advanced Western society, we’ve completely forgotten about our own animal side. Or maybe we feel ashamed of it and therefore don’t want to see it? In a way, your work reminds us of this.

Yes, you’re right. Unfortunately, one of the things that technology allows us to do is to separate ourselves even further. The reality of evolution is that every species is perfectly adapted to the environment it lives in. We’ve actually all evolved to be our best selves. There’s no witness, no kind of hierarchy that dictates that we’re better than any other creatures. We’re well adapted to this world, but so are rats and bacteria.

At the same time, Darwin’s theory also includes the concept of “survival of the fittest”, suggesting that there is a fight for survival between different members of a species, or even between species. But people like Kimmerer tell us that this is not actually how evolution works. It works through cooperation – species need each other to survive, and we have fantastic examples of this. We now know, for example, that mycelium was the first root system for plants when they were evolving, because they didn’t have roots of their own. They couldn’t get nutrients from the soil, so mycelium was the roots, and then eventually the plants grew their own roots. But those roots were still communicating with mycelium. We now know that mycelium gives nutrients – such as minerals from rocks to trees – and through their roots, trees give carbohydrates to mycelium. It’s all cooperative. Forest aren’t a bunch of individuals trees – instead, they’re all connected.

As renowned mycologist Paul Stamets explains, we humans share fifty percent of our DNA with fungi, and we contract many of the same viruses as fungi.

That’s why there are a lot of mushrooms in my work. Did you notice that the Shoeforms have a lot of mushrooms?

Patricia Piccinini. Shoeform (Orchard). 2019. Photo_Mari Volens

Of course. Especially chanterelles, which also grow in Latvia.

I love chanterelles. I know you value them, too, but they’re quite undervalued here in Australia. And just up until recently we didn’t even know that they communicate. They don’t have eyes; it’s all through touch. Mushrooms are very sensual organisms.

Patricia Piccinini. Shoeform (Bloom) 2019. Courtesy of the Artist

Speaking of science, is science the tool that helps us to understand the world, or is it perhaps art that helps us to do so? Or is it maybe a collaboration between the two? After all, your work is also a collaborative process between different disciplines.

The way I see it, if I was making work 500 years ago, I’d probably be painting something like the Stations of the Cross. I’d be trying to talk about the world through religious narratives. Today, however, those narratives don’t have the same value, or they’re not recognised. And before religion there were mythologies, Greek mythology and so on. Currently in the Western world, the dominant narratives are science narratives, so that’s why I’m looking at them. They’re the way we describe the world around us; they’re the mythology or religion of our time.

I use science as a narrative that we’re all familiar with, and through this I talk about things that are deeply important to me, such as our responsibilities to the other creatures and organisms around us.

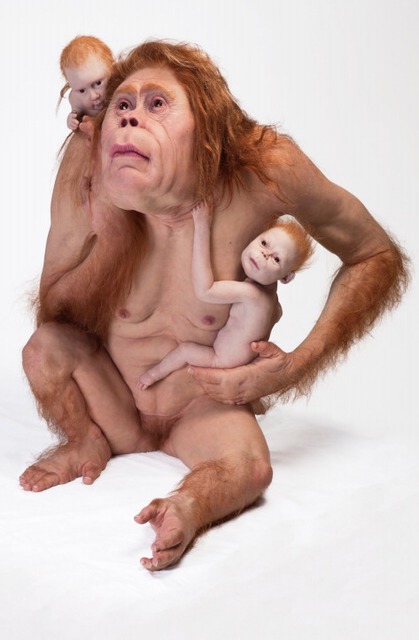

Patricia Piccinini, Big Mother, 2005. Photo: Mari Volens

Look at Big Mother (2005), for example. That work has a strong narrative (it consists of a large baboon-chimera nursing a human infant in a diaper – Ed.), and as humans, we can decipher it. Here’s a creature; she’s neither a baboon nor a human, but her eyes are very human. The eyes very much carry the narrative of this work. It’s a relationship between the chimera and a human, where she seems to be a carer, because she’s breastfeeding the baby. We can instantly see this, and we can also see that there’s a deep connection, because she’s actually physically connected to the child with her breasts. When we look in her eyes, we see that there’s an emotional connection as well. But because we can look into her eyes, we see that there’s something there that makes her not at ease with the world. She’s compromised. Something’s not right. Even though she has this beautiful connection with this human baby.

For me, this work is full of questions: Where are the parents? And what’s she doing? Is she taking the baby? How has she achieved the kind of status in our society that gives her autonomy, agency and a relationship with this child? Or is it the opposite? Is she some sort of servant creature? How do we, as viewers, feel about this relationship? Does it make us feel uncomfortable or optimistic? In a world where care is often assigned to others, these sorts of ethical questions about caring are vital.

Patricia Piccinini. Sanctuary, 2018. Photo: Mari Volens

You’ve said that the individualism of contemporary Western culture is one of the key problems of our age. Individualism leads not only to separation but also to loneliness. It’s an absolute opposite to oneness, to interconnectedness. How could we return to that? Could we return to oneness through the ethics of cultivating empathy, which is also fundamental to your work?

You’re talking about something that the Western world has really legitimised – the notion that it’s OK for me to live my own life focussed on my own personal happiness. If I can get away with it, I can do anything I want and I have no responsibilities towards anyone else. If other people get something good out of me making my life better, that’s OK, but that’s not what is important.

That’s a very prevalent, contemporary idea, and I think that’s something we need to look at as a society, because it’s pretty toxic. What we really need to think about is our responsibilities to others – and I mean others in the widest sense. For me, this is what our primary concern should be. It’s OK to make your life better, but not at any cost. You’re still responsible to other people, to other beings. My convenience does not justify any act. We really have to look at nature, because all these species around us are dying out. What are our responsibilities to other animals? What is our relationship with them?

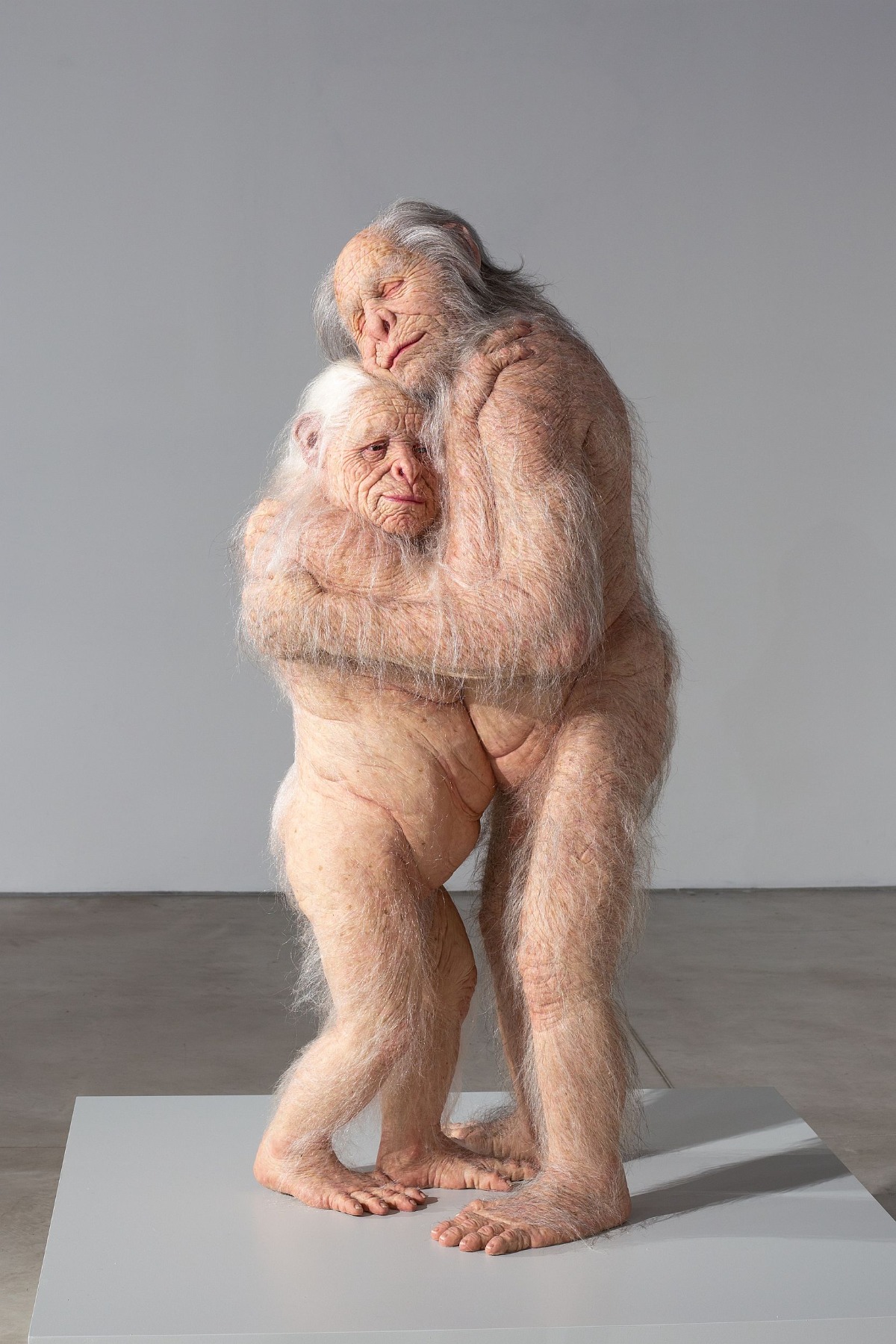

Patricia Piccinini. Kindred, 2018. Silicone, fibreglass, hair, 103 × 95 × 128 cm / Credit: Courtesy the artist, Tolarno Galleries, Melbourne; Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, Sydney; and Hosfelt Gallery, San Francisco

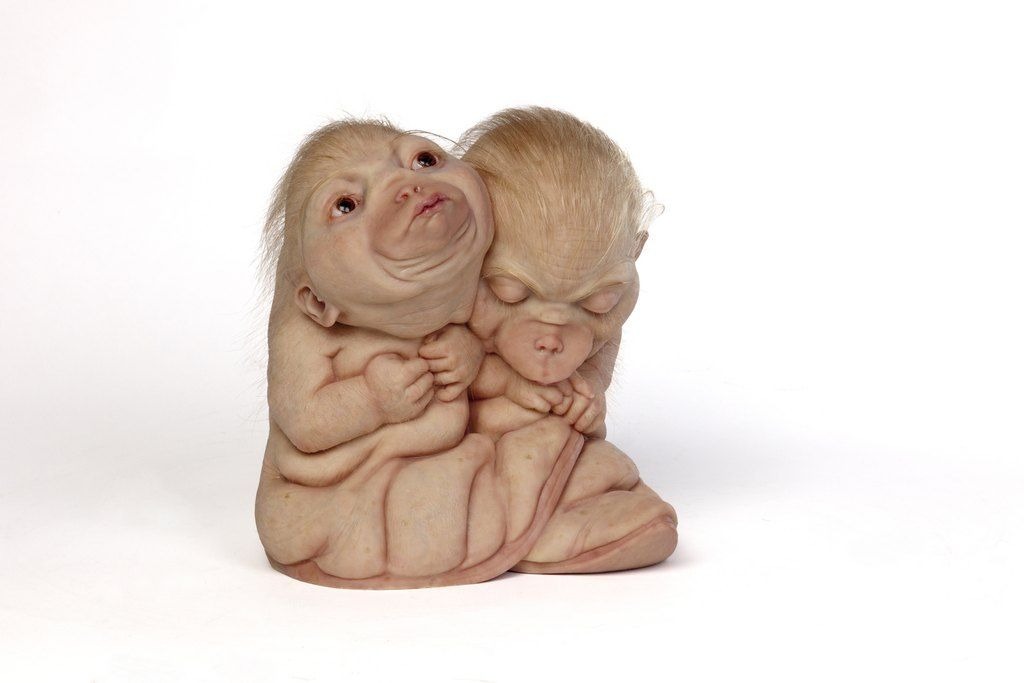

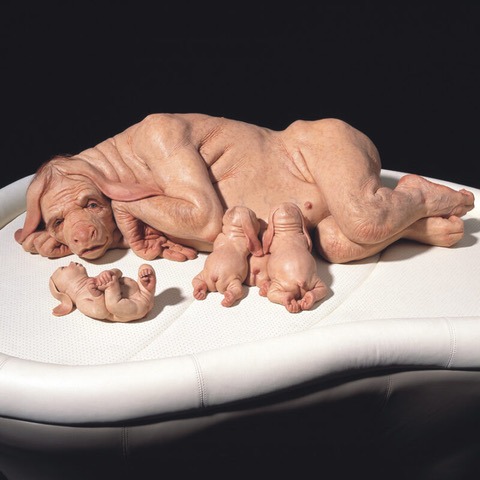

You mention the idea of empathy, and that is really central to my work. Because one way of thinking about your responsibility and connection to other people is being able to imagine yourself in their shoes, in their lives. (Piccinini shows her work The Young Family [2002], which is a mother-chimera with her children – Ed.). What would it be like to be this mother? What would it be like to think about myself as part pig, part human, knowing that I’ve been grown to make replacement parts for humans? What would it be like to be a mother knowing that your children are going to be cut up, paired up and used to help humans? And once you have this connection, then you can think about what our responsibilities to this mother are. Is it OK to do these things to her?

Patricia Piccinini. The Young Family, 2002. Silicone, fibreglass, leather, human hair, plywood; 85cm high x 150cm long x 120cm wide approx. / Courtesy the artist, Tolarno Galleries, Melbourne; Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, Sydney; and Hosfelt Gallery, San Francisco

I really try to bring empathy into my work, but it does make things more complicated. When people come up to a work like this, their first thoughts are that she’s ugly, she’s not a human, she’s strange, naked, fat. So they push her away. Then they come back to it and see this beautiful nurturing, the care that she has for her children by breastfeeding them. Her eyes are thoughtful, and you think, “I’m like her. I don’t think I would want my children to be used like that.”

Then, when it seems simple, it becomes difficult again, because you ask this question: Would you sacrifice her children to save your children? Would you use her body, her future, her relationships to save yours? And that’s the big question I think we all need to talk about together.

What do I actually feel? A lot of the time we’re told what to feel – in movies and things like that – so we’re not often given space for our own personal experience. Real life questions are hard, and we often have to give something up to do the right thing.

What is the territory that artwork inhabits? On the one hand, it’s a physical object created by you, your creative child. On the other hand, it’s a self-sufficient entity.

Well, I’m 55. I grew up during the theory boom. I witnessed “the death of the author”, but now I’m thinking that intentions are really important. They may not be written out in words, but I think that there are multiple layers of meaning in my work; all of those intentions, all of those layers are there. Of course, some people might not see them, and that’s where I don’t have control. Sometimes people just walk by, like, this is too ugly, it’s ridiculous, too histrionic, too emotional, too feminine. I can’t control that, but I can make a work that has a lot to say if you want to look for it.

As I see it, there are all these layers of meaning. Take Kindred for example. The surface of it is covered with human hair, and the skin seems so real. That’s the spectacle of it – the detail, the technique, the scale. Then there’s the conceptual level, which is this idea of a chimera between a human and an animal. We see this gradation of humanness/animalness, a bit different in each of the figures, and we wonder about our own animalness. Then there is the emotional level – it’s a mother and two little ones. And we look at this family and we think: “Oh, that’s a family. How do I relate to this idea that they have the agency to reproduce? How does that make me feel about my control over this technology? How does that make me feel about how they can have their own lives, without humans being in control of them?”

That’s what I see as the key to Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein. In that book, Victor Frankenstein creates a female “monster”, but he rips her apart when he sees the original monster approaching. He thinks, “They’re going to go off and have their own lives, reproduce, be beyond my control.” He can’t bear that, so he kills the female in front of the male. Perhaps he can’t bear the fact that the female has the potential for sexuality and reproduction, which undermines his own ability to create life. That’s too much for him as well. From there on, everything in the novel is just violence; there is no coming together, no reconciliation. There’s nothing. There’s just violence.

Patricia Piccinini. Shadowbat, 2019. Photo: Mari Volens

Have you ever asked yourself what it means to be an artist? Is it some kind of universal initiation (the artist as shaman), or is it a profession you’ve learned at art school? Or a combination of the two?

Having done this for thirty years, my idea of what an artist is has really changed. When I was twenty-five, I thought being an artist meant being alternative and having a great life. Peter, my partner, and I set up our own gallery. It was in a basement, and we did it without funding. We did any shows we wanted. It was a social thing – we would just turn up and have fun. And people sometimes did crazy things. Somebody once lit a huge fire... we could have all died in there. It was just crazy, even though we were quite serious.

However, I’m now at a point where I get more opportunities, and with that I feel more responsibility. It’s my job to look around me, to look at what’s going on in our world and encourage conversations about important issues. We can’t leave it up to politicians and corporations, because they have their own agendas. Let us – me and you, scientists, theorists and the public – let us all have a conversation about these important issues. It’s not going to be the kind of conversation that you learn about in an economics course; it’s going to be something else, something new. That’s my job, trying to start these conversations. Ultimately, I’d really like it if I was part of making a culture that is better for all of us.

I’m a feminist, and recently I’ve had to deal with misogynists, and I would really love it if our daughters didn’t have to deal with that. I would like to help get rid of that. I already love being part of the conversation about how we relate to the environment, about generating ideas that will help us to be more responsible in how we treat nature and other animals.

I’m trying to make the world a better place. That’s not a very “arty” thing to say – it’s not very cool, it’s too goody-goody – but I think it’s time to act now. If I could be part of whatever actions are needed to create a world that’s sustainable for future generations, I’d be happy. My life would have value.

How strong do you feel is the voice of art and the power of art nowadays? In this world of noise we’re living in right now?

I think art does have power. It’s not intense or obvious, but that quietness is actually important. When people enter a gallery or a museum, they come in knowing it’s a place to contemplate and to think about things. They often leave with more resolved opinions about things that act in the world. Even when people see art in different contexts, online or in the street, it can shift their thinking.

I do believe that people can have transformative moments in front of an artwork, including my work. A work like Kindred might make them think that they’re just like these orangutans. Maybe that realisation might make them think differently about things they do that impact orangutans. They might wonder, “Do I need to eat food with palm oil in it? No, perhaps I shouldn’t, because I feel our connection and I value what they are.” These are not easy things to learn, and they’re not traditionally encoded in our ideologies, such as economics.

Before becoming an artist, I studied neoclassical economics, which is all about the individual and the choice of the individual. It’s about the meeting of production and profit, and there was never any questioning about whether the whole system was any good. I felt I needed to be in the art world to talk about these ideas.

Do you think that museums and galleries are the right places to experience the power and true essence of art?

Interestingly, last weekend I did a very public project in a very different context. Skywhalepapa is a hot air balloon sculpture, the male to the female Skywhale, and he’s holding nine babies. He’s a very nurturing figure. The idea that a masculine figure could be a primary carer for children is a great thing to celebrate. In Australia, there has been a real shift in male attitudes to parenting, and that can only be a good thing.

This was a very public work. It was outdoors, and several thousand people gathered to witness it. The Three Mills Bakery had made Skywhale croissants specially for this event with sustainably farmed, locally milled, purple wheat and peach-and-honey cream filling that was like milk – milk from the breast of the Skywhale. Pheno (aka Jess Green) had written a beautiful song called “We Are the Skywhales”, which was performed live as he lifted off. It started at 5 am, and we got there when the moon was still out, and we saw the sun coming up. We were all together, and there was this amazing sense of community. The next day, Skywhales were on the front page of the newspaper, not as the balloon itself but as a political cartoon. When you think about it, that’s another way of bringing art outside of the museum and into the public world.

So yes, I’m interested in making work outside of the gallery, especially because the art world is a very tricky place, with very strong boundaries around it. At the same time, I do think that museums are great places, because they support artists and house the work and make it accessible for people.

I think that the distinction between high and low art is shifting, and museums are possibly becoming more important. The kinds of people who go to museums are not the people who go to art fairs. I think it’s driven by young people, who are more open to a wider definition of what art is. They come in and they say, “Oh, this is a knitted thing, or this is something about a pop star or I don’t know what.” And it’s all still art.

Patricia Piccinini. Sapling, 2020. Photo: Mari Volens

Making art is a mysterious process. Have you discovered how it happens? What is an act of creation? What happens when you make art?

Well, the traditional idea of what an artist is is the male genius. Going back to the Renaissance, it was a male genius directly connected to God. Obviously, I don’t fit into that category; that’s never going to be me. As women, we’re not seen as geniuses anyway.

I’ve met lots of these male geniuses, and they’re not that smart. Obviously, I don’t really want to be part of that idea of what an artist is, because I think that’s just another example of the cult of individualism.

For me, making art is simultaneously miraculous and very ordinary, a bit like birth. And like giving birth, it’s labour, it’s hard work. I look around the world, and I wonder what are we all talking about, what is important? Let’s have a conversation about that, and what can I add to that conversation that hasn’t already been said? I respond to the world, and sometimes the world responds back.

In one of your previous interviews, I think it was shortly after the Venice Biennale, I read that you met a couple of girls who had come to Australia as refugees from Sierra Leone, and they told you that, thanks to your work, they were happy to see the name of their country in a positive context rather than a tragic one. And you felt very honoured by that. Have you thought about what emotional or intellectual marks your birthplace has left on you? Are they in some way connected with what you do in art, I mean, subconsciously? At what age did you leave Sierra Leone?

I was three. I mean, Sierra Leone is a very tragic place. The English made this territory – it straddles three different peoples and their territories, and the English put them all into one country. On top of that, Freetown is the place where the English sent a lot of freed slaves to in the nineteenth century, and those people came from all over. It’s a resource-rich country, and whenthe English left, they left a power vacuum which descended into chaos that has only recently resolved. There was civil war and atrocities. My parents were post-war European economic refugees looking for work, and they ended up in Sierra Leone. My mother was a teacher, and she taught history at an African girls’ school. She wasn’t really privileged, but she was white. My father worked at a construction company.

In the late 1960s there was a lot of fighting, a lot of killing around, and one day the fighting came into our house. At that moment my parents said, “We can’t stay here, we have to go.” I was three. I think that if that hadn’t happened, I would still be living in Africa.

However, because we were white, we were able to leave. Plenty of African people wanted to leave and escape the violence as well, but they couldn’t. If I have feelings, they’re feelings of guilt. We were able to go, but other people had to stay. Even though it’s a very beautiful place, it was a violent place. It seems very unfair.

I migrated to Australia a few years later. My experience of not having roots in this place has made me the kind of artist who doesn’t want to be outside of the community. There is this traditional idea of the artist as “outsider” – somebody who is outside of a community looking in and telling everyone what’s wrong with them. I hate that idea. What makes that artist think they know what’s best for everyone else?

I’ve always wanted to be someone inside of a community, and I tend to try to make work that connects people, that listens to them, because I want to be connected to people myself. I have no roots here, but I’m trying to make them. It takes three generations for a migrant to feel comfortable in a country. My children, or their children, will really feel like they’re Australian. I’m Australian, but I really hold on tight and try to foster things, because I feel very unstable.

Patricia Piccinini. Eulogy, 2011. Photo: Mari Volens

The Aboriginal land in Australia, where you live now, is crisscrossed by thousands of “songlines” that link people to their land, their ancestors, animals and plants. Storytelling and interconnection is also at the core of your work. Is there any connection? Has living in Australia somehow inspired the way you look at the world, how you create?

Well, when I first met my partner, Peter, he was working in an Aboriginal community in the middle of Australia called Mimili, which is about seven hours away from Alice Springs. I spent time with him there, and I was introduced to Indigenous people through Peter. He was learning Pitjantjatjara, which is one of the hundreds of Aboriginal languages. These are people who were left alone for a long time, because white people didn’t want their land, and their culture is very strong.

This was my first real experience of Indigenous culture, and it was quite unusual at the time. It’s only recently that Australians have really started to acknowledge what was done to Indigenous people and culture. The truth of colonisation is that this is their land, and we stole their land, we killed the people, and we’ve tried to destroy their culture. More and more people are interested in making amends for this, although there is still a lot of unwillingness. People like me think that we should give Indigenous people their land back or pay some sort of rent or reparations. This is a very important and very current issue.

With that as context, I don’t have the right to tell Indigenous people’s stories, because they are their stories. And that’s the way it has to be. Those stories belong to very specific people with particular connections to places, and to me, as a white person, claiming some sort of connection seems both disrespectful and disingenuous. I don’t like that, and they don’t like it either. Indigenous people have the strength to say, “We own these stories.” Non-Indigenous people should say, “Yes, we value your stories, we value the way you’ve looked after the land, we value what you’ve done, and we value your culture.”

Having said all that – and that’s a really big thing – I think that the thing we can learn from Indigenous people is the way that they explain the world as a kind of a fable. That’s how they talk about the world, and I really connect with that. That’s what I do with my work, too. I’ve had Indigenous elders from the community say that to me, “Oh, we do the same thing.” I talk about relationships and how we relate to land and so on. And they do it, too. Completely differently, but that’s what they do.

Patricia Piccinini. Instruments of Life. Exhibition view, 2021. Photo: Mari Volens

We’re now entering the second year of the pandemic, and it’s clear that we’re going to have to learn to live with this virus, and probably future viruses as well. What the pandemic has brought home to people is that we can’t go back to the way things were. In the meantime, we don’t have very clear alternative solutions about how to move on. The key word of our time is “uncertainty”. What kind of culture could stem out of this notion of uncertainty?

Well, I do think it might be a culture of gratitude. When you can’t rely on things being there, then you’re much more likely to realise that what you do have is great. Hopefully you’re going to look after it.

I already mentioned the Skywhales. Last Sunday we inflated these two big hot air balloon sculptures, and our aim was for them to fly off. We choreographed the whole thing, we had the song, everything was timed, we had rehearsed it, and it was going to be just like the perfect performance. And it was a beautiful day with no wind. But a wind was exactly what we needed for the balloons to fly. So everything that we had planned and expected, everything we paid for, was disrupted. But what the hell, is this failure?

In the end, the balloons didn’t fly, but something else happened, and we experienced it together. We did inflate them, and they stayed put, but this meant that the people had a chance to actually stay with them. They had the chance to really look at them, because they didn’t fly away. In the end, people said it was actually OK that the balloons didn’t fly, maybe even better. That’s the thing about this project. It relies on nature, and even though we think we can, in the end we can’t control nature, you can’t tell nature what to do. We want the balloons to fly, but it’s up to nature to decide.

This is one of the few times in life when people don’t get what they want. If you’re in a gallery, you can turn the light on, and it’s on. Outside, you have to have the right wind conditions. If the world doesn’t want to give them to you, then that’s it. That’s instability, uncertainty, which institutions don’t like. However, for us as a group of people, we went, “OK, the situation is unstable, we can’t control it, but actually what we have is this moment together. Eating croissants, listening to the music, being here with these big sculptures, watching the sun come up. It’s actually pretty wonderful. I’m grateful for that. Maybe in the future the balloons will fly. Who knows?”

I was really amazed by this feeling of gratitude. I’m lucky to have what I have. I don’t have everything but, you know, it’s great.

You had that day.

Yeah. And that’s good. I think about what’s happening in the world, with scientists saying that environmental collapse could happen already in thirty years. It makes me think, well, I’m so lucky that there are these beautiful trees outside, that birds are singing in them. I’m so lucky to be with them. So now I’ve got to act and help.

Patricia Piccinini. The Coup, 2012. Courtesy of the Artist

Title image - Patricia Piccinini with her artwork 'Shoeform'. Photo: Alli Oughtred