Art is my comfort zone

An interview with Polish artist Paweł Kowalewski

Paweł Kowalewski’s name (1958) is closely connected with the legendary Gruppa – Poland’s most influential artist group of the 1980s. Polish artist Kowalewski was one of the group’s founders, along with five like-minded peers from the Fine Arts Academy in Warsaw: Ryszard Grzyb, Jarosław Modzelewski, Włodzimierz Pawlak, Marek Sobczyk, and Ryszard Woźniak. Kowalewski’s activities with Gruppa culminated with his participation in the 1987 edition of Documenta in Kassel. At the very beginning of his career, Kowalewski developed the concept of "personal art, that is, private art", meaning that his creations are strongly connected to his personal life, but they are also linked with the context of the time in which we live and associated topical issues. An important element of Kowalewski’s work is the political dimension, which over time has become its central axis.

Paweł Kowalewski. Photo: A.Świetlik

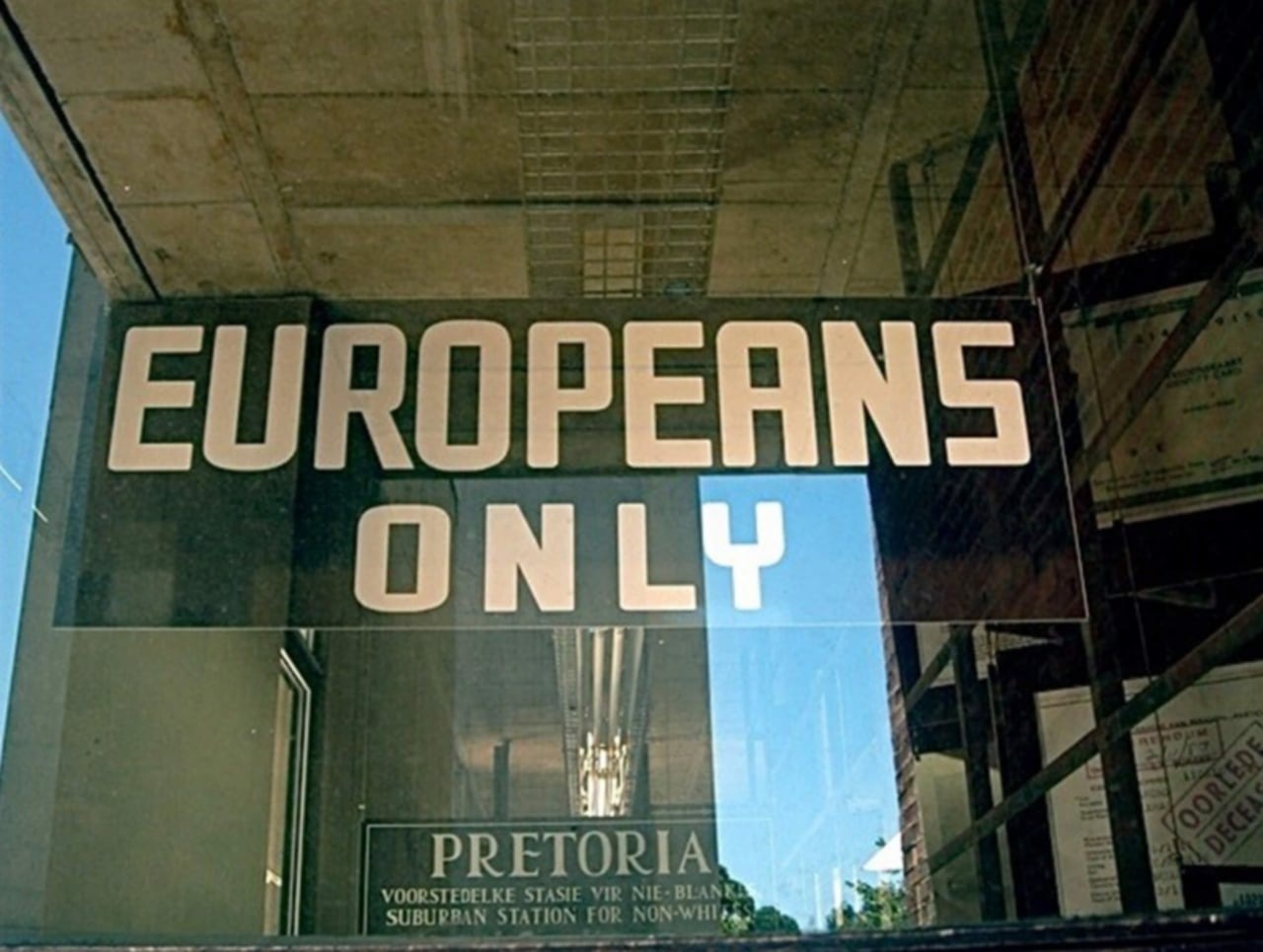

Kowalewski has been a lecturer at the Faculty of Design at the Academy of Fine Arts in Warsaw since 1985. His works can be found in Poland’s largest collections, including the National Museum in Warsaw and Zachęta National Gallery of Art. Kowalewski’s works have been shown at Tel Aviv Artists House (Israel), NS-DOKU in Munich, Museum Jerke in Recklinghausen, the Dorotheum in Vienna, Sotheby’s in London, the Museum of History of Photography in Krakow, and elsewhere. Last year, his photograph taken in 2010 at the Apartheid Museum in Johannesburg showing the Pretoria railway station from the apartheid era (1992), was included in the group exhibition Tell me about yesterday tomorrow at Munich’s Documentation Centre for the History of National Socialism. The sign captured in the photo – EUROPEANS ONLY – epitomises a system that divides people based on race and skin colour. The exhibition was included in the list of Top 10 Shows in the EU of 2020, as compiled by British art magazine Frieze.

Paweł Kowalewski. Europeans Only, 2010, lightbox

Paweł Kowalewski is also a passionate art collector, and has in his possession works by such renowned artists as Marina Abramović, Jasper Johns, Robert Rauschenberg, Jörg Immendorff, Andy Warhol, Jeff Koons, Zbigniew Libera, Dan Reisinger, Victor Vasarely, and Krzysztof Bednarski.

Kowalewski’s solo show, Objects created to stimulate the life of a mind; the invisible eye of the soul, will open in May at the Winda Gallery in Kielce, Poland.

Your works have always been about the “here and now”, yet at the same time they tell us that the future cannot be separated from the past. What are the main lessons that we, as a society, should learn from the current “here and know” – a time that, unfortunately, also includes a global rise in authoritarianism, worrying signs of censorship, discussions of “cancel culture”, the right-wing Polish government’s restrictive abortion laws, etc.?

I’m very positive; I think that, especially in the context of the pandemic, we must sustain optimism. Comparatively not that long ago – in the era of communism – we couldn’t even imagine things such as free Baltic States, freedom in Poland, and so on. What I think we’re going through right now is a kind of series of childhood illnesses. We are young democracies, you know – we still have to find cures for these bouts of nationalism and such things. What are the politicians doing right now? They’re playing the piano. The current abortion issue in Poland is a very good example of how politicians are just acting. They are acting as if there is an issue that divides many nations – from America to Poland. They know that they are dealing very poorly with everything concerning the coronavirus pandemic, so they’re just throwing the people a bone with which to keep them busy so they don’t think about how badly the government is handling the pandemic. But I think that they’ve simply miscalculated. I too think the abortion issue is important, but it’s much more important to the young people. And by acting in this way, the politicians are losing the young people forever. It will be a tragedy for the Polish Catholic Church and for the conservative right wing as a whole because they will loose the young people.

You know, when the left side becomes too radical, that’s also not good. But that is exactly what’s happening right now, and if this situation ends up pushing the young people more towards the left, it will be a real tragedy. But I’m optimistic that two and a half years from now we will change the government; we will change everything, and it will be normal again.

I’m much more afraid of what’s going on in Russia right now. Putin is being pushed into a corner, and when a dog is trapped in a corner, it not only barks but bites. This is a very critical sign.

Paweł Kowalewski. Die bombe, 1986, oil on canvas, 140 x 100 cm, collection of the District Museum in Bydgoszcz

You once said in an interview that you divide art into just two categories: good and bad. In your opinion, which kind dominates today’s art world?

I think the first time I said something like this was early in my youth – in the early 80s, still in the Soviet era. I was very fascinated by two phenomena: one was social realism, and the other was the National Socialism of Nazi Germany. And, you know, in the end, nothing has changed. It’s not totalitarianism or some other system that makes art bad; the art is bad when it’s not coming from the artist – when he’s not using his gift of being much more sensitive than other people. And also if he’s using art just to make money – just to answer the market’s needs. I really believe that true art is very personal. It must be like a transmission of everything the artist sees, everything he feels. It goes through us and we just put it on the table. And it doesn’t matter whether it is a movie, a painting, a sculpture, or whatever.

One of my favourite directors is Andrei Tarkovsky, and for me he is distinctly visual; you can see how sensitive this man was. Many directors have made films about war, and Tarkovsky’s first film was also about war, but the difference is obvious. As an artist you must be faithful to your own sensitivity. I think this is the answer.

There are no criteria for recognising good art. It is like a gut feeling. Of course, sometimes we can also be mistaken, but this gift of being able to sense it is in each of us – we can feel what is good art.

You are a hybrid of an artist, businessman and collector. How do these three aspects coexist in your life? Is there a balance between them, or does one or another periodically dominate? If the latter is true, which one is in the forefront right now?

I’ve never stopped being an artist. I’m also a professor at the Academy of Fine Arts here in Warsaw, so I have to be an active artist or else I wouldn’t be able to give anything to my students.

This is a question I frequently get from other artists – how can you be an artist when you’re doing business? The business side is what gives me the freedom to do what I want as an artist. I don’t look at what people are buying from me – what they think is good, or what they think is bad. I know that there are people who are losing their minds over some of the paintings I’ve done in certain periods of my life, and that my earlier works are being sold for huge sums. Should I follow this and keep track? No; that would be going against myself. This is the first thing.

The second thing that this freedom gives me: when I go to the studio, I’m not going to work. I’m doing it at my pleasure. It’s my love. I have a space for myself, and nobody can touch it – nobody can influence this.

Art, for me, is a very personal thing. For example, I’m now painting bigger pictures than ever before. In a sense, I’ve returned to painting – because I had also been making photographs, objects and installations. So, I don’t see any limits, and this was the whole idea behind Gruppa, which was formed by me. It was like the idea of being free, of freedom. Imagine, at the end of 1970s, the conceptualists were taking over the art scene; they saw my pictures and said, Oh my God, you want to crush painting? I said no, my painting is very crazy, it’s very sensitive; but the question I was asking myself here was – if you can make a photograph, if you can make a video, if you can make an installation, why can’t you paint? Why is this being excluded from conceptual art? So it was quite a funny beginning, and from that point on it’s been much the same.

Paweł Kowalewski and Zbigniew Libera, Ryszard Grzyb and Włodzimierz Pawlak, in Dziekanka Gallery in Poland. Photo by Zygmunt Rytka

How has the Polish art scene changed since the Gruppa years? How strong is the voice of art in Poland now? For example, last year we interviewed Polish art collector Piotr Bazylko, and in speaking about the local scene he said that “art is not considered to be an important matter here. For local politicians, it is more important to build a new football stadium instead of a new museum.” Do you agree with him?

If you ask an artist of any country – except for perhaps the three nations of France, Germany and the USA – the answer will most likely be that art is not considered important. But, in fact, artists are running the cultural politics. If you open up an issue of, for example, Die Zeit or Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, art is everywhere. So, culture is a part of politics.

I’ll tell you an anecdote I recently heard about Brexit. This crazy guy, Boris Johnson, was negotiating how the trade deal will affect fishermen. The fishing business there is worth 1.5 billion pounds, yet, at the same time, he forgot about the musicians. As we know, the British music scene is worth 5 billion pounds, and with Brexit they now have problems in terms of coming to Europe.

If you look at France, if you look at the USA and at all those foundations – if you start in a healthy way, art can give back. And when you see these small German cities with wonderful museums, I think that they really believe that art can change people. Or look at the Miami design district – it has changed the city completely. If you start to treat art as being serious, it will end up playing a serious role.

In our countries, art is not being treated as seriously, but even [the Polish] government is still building the new Museum of Modern Art. They don’t understand why, but they do know that in all capital cities there must be an institution called “The Museum of Modern Art”. So in this sense, I think that things are not so bad.

The number of private collectors is growing, and in Poland as well. And if you look at the EU’s strategy of a New Bauhaus... OK, so the [original] Bauhaus went bankrupt at the end, but if you look at how it has payed back in terms of German design – in everything – you can see that the power of art is very, very great. I think it will be a relatively slow process, but I am convinced that in the next ten years, this region of Europe will experience interesting moments.

If you ask me about the past, you know, Gruppa did break down some walls, and the artists who came after us – like Miroslav Balka, Wilhelm Sasnal, and Piotr Uklański – it was much easier for them. At first many attacked us – they grabbed us by our necks and demanded: What are you doing? You are killing painting, you are killing art, you are just doing something and not in the proper way. And I think a lot of my colleagues, also from Gruppa, began to be much more polite; they wanted to be good painters. Such as Jarosław Modzelewski – he is a great painter, and he wanted to be a painter. He took part in our performances and he would make something, but to me he seemed much more calm.

But for those who came after us, it was much easier. I’m not jealous of this; we made something. There must always be the first one who will start to break down the wall. And when it’s done, the wall has fallen down. This is the story.

Paweł Kowalewski. Zdzisiek jumps every night with a bottle of petrol, 1982, oil on canvas, 100 x 80 cm, Wojciech Włodarczyk's private collection

Speaking about painting, does painting have limits, or is it as limitless as the more modern media?

Painting has no limits. You know, if you look at the movies, you can see paintings; if you just look around at the streets, you can see paintings. I’ve been an educator for about 36 years now, and believe me, my students recognise what studying classic painting and sculpture can give them – they understand that art inspires things even like automobile design. Art opens one’s mind, one’s eyes – everything.

I think that painting has no limits, and I have always played with it. Painting is simply a part of space. I take pictures of the sunrise, very early sunrises, and this is painting. And this is happening every day – the world is full of painting. Artists are just trying to find it and bring it to the people, but believe me, paintings are everywhere.

Paweł Kowalewski. Adolf Hitler and Joseph Goebbels open an exhibition of downgraded art in Munich, 1986, distemper on paper, 176 x 204 cm

You mentioned the idea of a New Bauhaus, which is currently being promoted on a European Union level as well. Do you think it’s possible that a new political vanguard or artistic group could be born out of this? Could it happen in eastern Europe? What is your gut feeling about this?

I have Jewish blood and I have Lithuanian blood – this part of Europe is very close to my heart. I had a scholarship in Heidelberg, which led to me changing my mind about Germany too – which was quite difficult for a Polish Jew. I think we contain a sort of inner awareness or conviction that we need to be united with the rest of Europe. So maybe it will happen here as well; I don’t know.

Of course, if you call it Bauhaus, one immediately thinks of Germany. There is a strong influence of German culture that I sometimes call “Kulturkampf”, but there is nothing bad about it because everybody knows who Joseph Beuys, Anselm Kiefer, Sigmar Polke, Gerhard Richter, etc. are. This is a good thing, but we should reverse it so that everyone know the names of some Polish artists as well. Bauhaus had this combination of various [ethnic] “bloods” because in those days, Germany was like eastern Europe is now. There were a lot of immigrants from Russia, Poland, and probably from the Baltic States as well. And it all boiled together and something very creative came out of it.

In 1933, when the Germans started to order and structure things in the Nazi way, all of the creative people left, and mostly for America. Many went to Black Mountain College and continued their work there. Concerning the ideas that came out of that, I believe that the most important thing in today’s context is that these ideas be realised in our everyday lives. Because for me, design (and we often overuse this word) is the way we design life and space around us – that which is around us. For instance, the importance of putting this little colourful sculpture in the park – how it changes everything, including the behaviour of people. How even a colourful shop on a corner can change the way we live and experience life.

We – all the post-communist countries – started to copy everything from this “land of dreams”, the West; we also wanted all these big shops and so on. But now things are changing, and it is probably easier for us because we never got completely used to it. For us, 70 years haven’t passed in this stage; it’s only been 25–30 years, and we’ve already managed to wake up from it. So, there is a chance for us to transition into a different kind of life. I don’t know how quickly this will take place, but it will happen.

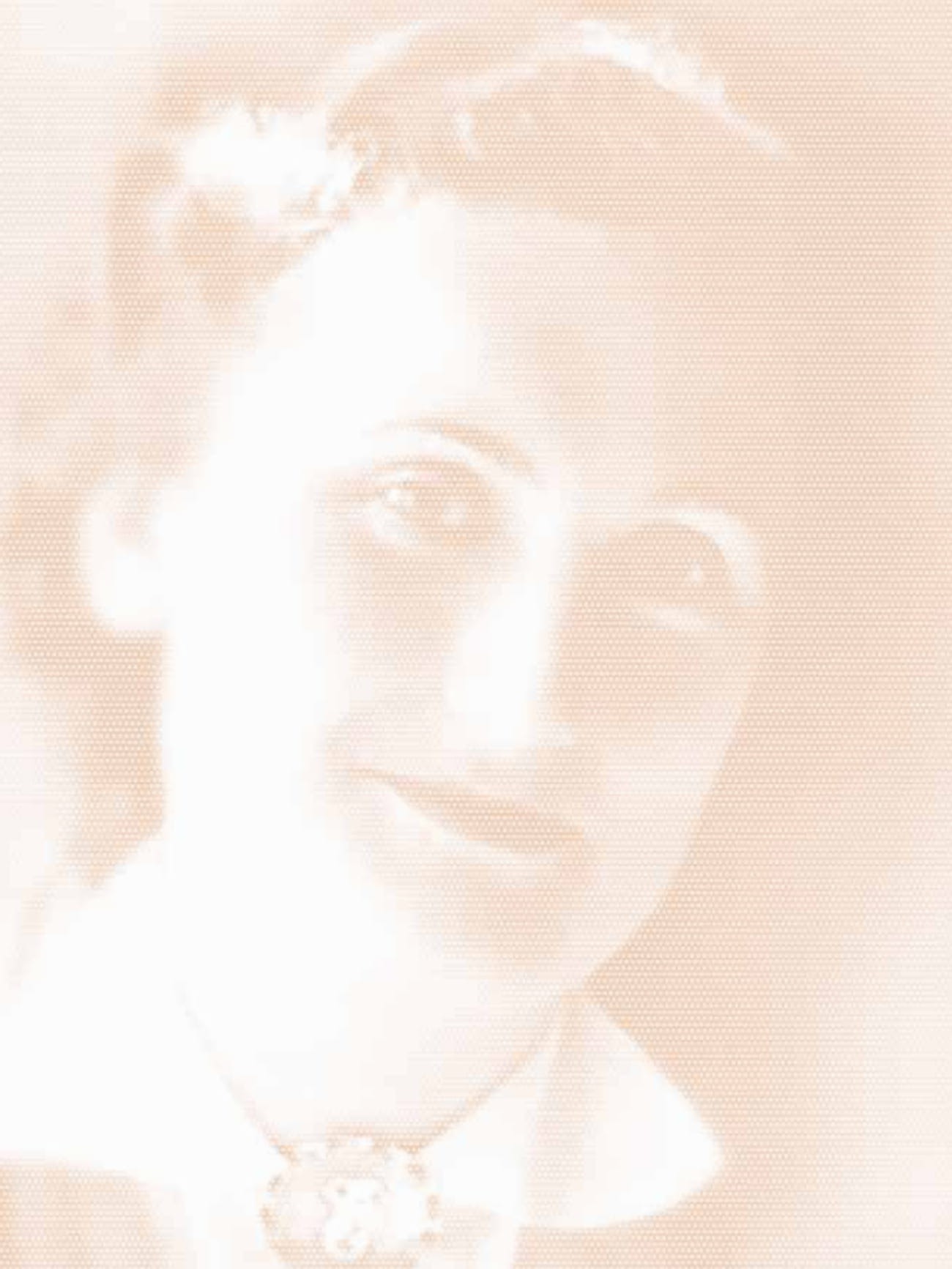

I myself feel more like an European than a Pole. It’s a complicated story, and every nation has its own history. In 2015 I had an exhibition in Tel Aviv, which was a homage to my mother. The title was Strength and Beauty. A very subjective history of Polish mothers, and it was dedicated to the young women born at the beginning of the 20th century, whose youth fell during the time of the Second World War and the development of the two biggest totalitarian systems. Believe me, seven years ago nobody was as focused on women’s rights [as they are now], and I was showing huge portraits (200 x 140 cm) of ten young and beautiful women, mothers of my Jewish friends, taken from archival photographs. I blew up old pictures and turned them into monochromatic style paintings.

Paweł Kowalewski. Strength and Beauty, Zosia, 2015, offset print on dibond, 180 x 140 cm

The tragedy of these young women was that they had to live through the era of totalitarianism, and especially the time of war. And the war was different for everyone. My mother didn’t know that she had Jewish blood, and this not knowing saved her life – she was blonde, plus, she was a woman. It was only a short moment in time, but it completely changed their lives; it’s hard to believe that these 18-, 23-, 25-year-old women could survive something like that. And they didn’t only survive, but after the war they became loving mothers, tender lovers and raised sons, some of whom later became generals in the Israeli army or successful businessmen. And everyone who knew these women always spoke of their warm hearts and kindness.

But these years of their youth were full of horrors. One of the most shocking stories I’ve been told was about a young Jewish woman who lived in Warsaw. One day she was crossing the street and suddenly a German officer stopped her and said: You are Jewish. She replied: You are just kidding, don’t talk to me like that. When she got home, she didn’t leave for two weeks. Then the police came – they knocked at the door of her apartment but she ran away. When she came back home, she found that her father had committed suicide and the police had taken their money. Now she was alone with her dead father’s body in the kitchen, in occupied Warsaw. She was 22. There was nothing she could do but cut up her father’s body into pieces and throw them into the Vistula River. For God’s sake... and this is only one story from her life. After her son retold this to me, he said: Every time I cross the Vistula, I’m looking at the grave of my grandfather. And you have to live with this. But you are also a tender mother and you give your son love and warmth.

So, this exhibition was very special for me. I printed these pictures with a special paint that disappeared over time – much like our memories. And when those pictures travelled from one exhibition to the next, they never looked the same. Some of the pictures had received more light than others, and the images of the women could barely be seen. But they never disappeared completely – something always remained, like a light shadow. Just like it happens with our memories.

Even now, seven years after the death of my mother, I think about her; but these memories are fleeting, flickering. And suddenly you’re disappearing...all of us, we are disappearing from memory, and the story is how we should keep these memories alive for the next generations. I think this is very important.

In order to realise my works as I intend, I use the latest technologies, but the hardest thing was finding a paint that would slowly – in a year’s time – fade away, because most manufacturers try to create paints that last as long as possible. Per my strange request, they made a special paint in Germany. At first I wanted to print the photographs on silk, but it wasn’t possible to use this special paint on silk. So I booked a whole Heidelberg printing machine, which is huge – a whole system with about five sections – and they worked just for me. For each picture they have to run the machine and produce something like 500 copies, and they were quite perplexed as to why I wanted to spend such a huge sum of money for just one photograph. For me, it was not a photograph – it was a painting. I never made a copy of it. This is a holy thing for me, like part of my memory. This is the way I look at art.

Did you always – from childhood – know that you have Jewish blood in your veins?

I thought we were Christians because the story I had always been told was that we were Hungarian. However, the real story was that my grandfather was a Hungarian Jew; he emigrated to Warsaw because under Austro-Hungarian law, you couldn’t make a career for yourself if you were Jewish. So my family came to Poland and Christianised themselves. My mum had two sisters who look 100 percent Jewish, and I always wondered how they survived the German occupation. But there was a simple explanation – most Hungarians, as everyone knows, have dark hair and so on.

Like all Jewish men, I am circumcised. It was only when I was ten years old, taking a shower in a public bath (in those days the showers were completely open), did I first notice someone looking at me, saying: Wow, you are Jewish. From that moment on (this was in 1968) – and I’ve heard many Polish Jewish men say the same thing – even when we are alone in a public toilet, we always try to stand very close to the wall to hide ourselves.

I’m currently working on a very personal exhibition for which, among other things, I’ve created a statue of David that is quite funny. Because if you look at the two sculptures of David in Florence, they are not “true” Davids – their penises are wrong. Because both artists, Michelangelo and Donatello, just copied other statues from antiquity. They were rightly impressed by the biblical King David, but the real historical King David didn’t have a foreskin. Donatello’s sculpture is beautiful, but the image is of his lover. So I made a “real” King David, which is almost a copy of Donatello’s, but circumcised. It’s a tradition that is very important. You can hide as a Jewish woman, but you can’t hide as a Jewish man, because the first question you will always be asked is – take off your pants... And you could be killed just because of this, without any other explanation. Just a little piece of skin, nothing special. It’s horrifying. On the other hand, you know, it’s funny that art history has also been influenced by this.

Paweł Kowalewski. True David by Donatello, 2018, 3D print, gold, h 158 cm / Photo: A.Świetlik

I like a quote of yours in another interview: “One cannot have control over art. Art must always stay unrestricted.” Is art an ultimate truth? Is what we are searching for in art the truth?

You know, there was only one newspaper in the world which was called Pravda [the Russian word for “truth” – Ed.], and it was a Soviet newspaper and it was full of lies. So from this moment on, if somebody says: I’m speaking the truth, or when you name your party “Law and Justice”, like the party governing in Poland right now, you know that there is nothing of the truth there. Nothing of law, nothing of justice. When art begins to take on the role of a preacher of truth – and there’s a slew of artists trying to go in the direction of offering solutions instead of asking questions – that begins to frighten me. I think that good art should ask questions – because you’re never sure of anything. Perhaps we’re just part of a crazy guy’s dream. We don’t know. What is reality today? At this moment, I’m talking to the computer, and you’re talking to the computer – it’s changing our behaviour as well as the questions that we ask ourselves.

I think art gives us a kind of impression of what the world looks like and how it can look. Art just gives inspiration; there is nothing that can give us one right answer as the only one.

With the activities of Gruppa, you were keen on going beyond your comfort zone and making the audience do the same. What is the role of art today when being in constant change, always being beyond our comfort zone, has become our new reality?

Sometimes I’m very realistic. I recently made two big heads – four, five times the scale of human heads – for the same exhibition: two “golden boys” with open mouths, shouting at each other. And when you stand between them, even I’m afraid despite being quite a “big boy” myself. Their heads are covered with 24 carat gold, so they are real golden boys. One is Trump and the other is Putin. Someone asked me why am I doing this now, since Trump is no longer president. But he is even more of a “golden boy” because he is a warning about a new order entering our life. You can call it a new kind of totalitarianism in which, as long as you have a comfortable life, you can forget about what is going on elsewhere… pragmatism is what counts. One guy is putting Navalny into prison, the other is sending bison men to the Capitol...

But don’t forget, these guys are only faces – behind them stand thousands of other “golden boys” who are also thinking – what’s wrong with what I’m doing if it’s making money? You know, half of China is like that. Under Xi Jinping’s administration, around 1 million people are being sent to labour camps for re-education. And these are real concentration camps.

It’s very difficult, but on the another hand it’s very simple – the world has always been like that. And I think a part of me has been screaming about that from the very beginning. I’m so afraid that history will never forgive us – artists from this part of the world – if we return to this. We have the obligation for the next generations to scream very loudly, because we know which direction things are heading. And it could end very badly.

Compared to the Gruppa years, can we talk about powerful political art today and how strong its voice is – both in Poland and in a global context?

If you look at Ai Weiwei, and even other Chinese artists, they are trying to do something. They are not “golden boys”. I think there is a lot of political art. For example, one of my favourite pictures by Gerhard Richter is of his uncle. His uncle is pictured wearing a Nazi Wehrmacht uniform – is this political art or is it not political art? I don’t know. There are also a lot of things that are political in today’s art. If we look at Jeff Koons, this commercial guy – he made a lobster sculpture, and if we go in the direction of what the lobster means, it is political art. If you touch upon issues that are important right now, like women’s rights or racism, you can find them everywhere. Politics are a part of life, and it has been so since the times of ancient Rome and Greece. We humans are just animals who love to live in groups, and that is why it is so painful for us now.

It would be much easier for us to change the governing party in Poland if the youth had more of an understanding and interest in politics. And that’s happening right now because by implementing the new abortion law, the government has directly affected an important part of their lives, which is the giving of birth, procreation, etc.

You know, Nicolae Ceausescu, the dictator of Romania, did the same thing – a total ban of abortion and a total ban of contraception because he wanted to build up a “great Romania”. We all know how that ended. People are doing the same things again and again. Thank God we have art. Look at the demonstrations in Poland, it’s like social media come alive – they are coming with slogans, with ideas, with pictures. For me, it’s art.

I think that we are constantly moving upwards and getting better, but from time to time somebody comes along who wants to break it all down. Remember how growing up in the communist countries, they were always frightening us by saying that there will be a nuclear war, that the Americans will soon attack us? Nothing like that happened. The period of communism was hard; a lot of people sacrificed their lives, but at the end of the day, there was light at the end of the tunnel. Even looking at Russia, and at China right now, I think that one day things will start going in the right direction.

The most important thing is to continue to ask questions – through art, though the freedom of provocation. And we should keep doing this even if we are kicked out of our comfort zone.

Paweł Kowalewski. Totalitarianism Simulator, 2012, installation, Propaganda Gallery

In 2012 I made a work called Totalitarianism Simulator. It consisted of a big black box which you enter, and inside there is a wonderful white armchair. You sit down, the lights go down, and a huge screen shows pictures of all of the horrifying things that took place in the 20th century until the beginning of the 21st century. And next to these you see pictures of the same time, but showing normal life. Like a scene from Mussolini’s Italy, where soldiers are doing horrific crimes; and at the same time you see a picture of a happy family walking around the Duomo in Milan. Just like right now – we are sitting here and talking, but in the meantime, something horrible is going on somewhere else in the world. At the end of this “show”, you suddenly see your own face. The black box had a camera that took your picture while you sat in the chair, and a special program placed your portrait into the slideshow at the very end.

Again, I was not giving answers. I was just asking questions. The last picture was from Syria – it was just as the war was beginning there. People would come out after the six-minute show and ask: What do you expect me to do? Nothing. Ask yourself the question: Am I doing enough to protect us all? This was in 2012. In 2015, “Law and Justice” won the Polish elections. We didn’t make enough [works]; maybe I should shout louder.

In my opinion, that is one of the missions of art. I always like to say that the world would be a wonderful place if all politicians would read William Shakespeare’s plays – Macbeth and others. If they read them with understanding, they might not follow with the same mistakes. I really wonder how Putin can go to the theatre and watch Macbeth. What does he understand of it? What is going on in his head?

You know, artists warn you. Like on the motorway, when you’re driving and you see a speed limit sign – you can either understand it or not. If you are killed, then it is too late.

Paweł Kowalewski. Mon Cheri Bolscheviq, 1984, oil on canvas, 100 x 81 cm, Starak Family Foundation

We’re now entering the second year of the pandemic, and it’s clear that we’re going to have to learn to live with this virus, and probably future viruses as well. What the pandemic has really hammered home in people is that we can’t go back to the way things were. In the meantime, we don’t have very clear alternative solutions about how to move on. Do you think this pandemic will have taught us anything, or once it ends will the world return to the state it was in before?

I think this pandemic is a bumpy warning. In 1968 there was something called the Hong Kong flu. They say this epidemic took 2.5 million lives worldwide. My family, including me, all had the Hong Kong flu, and my sister still has problems with her heart because this virus affected the heart and not the lungs. In Poland the government reported the deaths of 25,000 people, and taking into account that the communists were in power, the true statistics were most likely twice as large. And this was just 50 years ago, not like the Spanish flu which was 100 years ago and which no one can remember. That is to say, we have had 50 years to prepare for this pandemic.

At that time in Poland the schools were closed for two weeks, as were the theatres and cinemas. Those were the only restrictions they enacted. The queues to the pharmacy were five hours long because people wanted to cure themselves, but there was a shortage of everything. And we survived only because back then we regularly bought large sacks of potatoes, celery root, and onions for winter. And we ate just that. I was sick for four weeks. And today no one remembers the Hong Kong flu. There were just a few articles in the media that mentioned it, and a chapter in the Encyclopaedia Britannica.

It all ended in the1970s. There was Woodstock, there was the landing of men on the Moon, there were riots in Czechoslovakia. Zillions of events. Did anyone talk about social distancing? No. What does that mean? We care much more about human life now.

You know, for Communist China or the Soviet Union, what difference does one million more or less lives make? Even in America at the time they were sending boys straight from school to the war in Vietnam. Actually, the Hong Kong flu was brought from Vietnam, because Chinese soldiers had been helping the Viet Cong and they gave them the flu. And as there were no direct flights from Vietnam to America back then (airplanes couldn’t make such long flights without landing to refuel), they made stopovers in northern Italy, West Germany and the UK. In the first two months of the Hong Kong flu epidemic in Europe, all cardiac hospitals in Lombardy filled up.

And things are repeating themselves right now, step for step. Everything is coming back.

In addition, there’s another thing that we white people have forgotten – we’re ignoring Africa. Remember Ebola? This epidemic would flare up in western Africa from 2013 to 2016. Imagine if the people there had travelled on such a scale as the Chinese had... And that’s a much more deadly virus compared to Covid-19.

But what we all now suddenly understand is that we are not gods. I had cancer, but I survived and I am alive. If the same situation had happened 20 years ago, I would probably be dead. Thanks to the advances of science and technology, we had begun to increasingly believe that we are gods. All these fairy tales about Bill Gates and others...; this imagining that if we have enough money, we can live forever. No, we can’t live forever. And that would also be very boring.

Paweł Kowalewski. I, shot dead by the Indians, 1983, oil on canvas, 80 x 100 cm, collection of the Museum Jerke

Do you think that the pandemic, in a sense, have changed our relationship with death?

Oh yes. I lived in the shadow of the Second World War. Both my father and my mother were in the Warsaw Uprising, and family members on both sides died. Death was like a part of life. Back then most people lived in the countryside, and to kill a chicken or a pig to feed the family was completely normal. Today we all have distanced ourselves from death; it’s always a tragedy, but in truth it is a part of life.

Death came very close to me, you know. Today, if you are elderly, you have a 25% chance of dying from COVID-19; if you have had cancer, like I have, the chances are 50%. Honestly, I was looking at 50:50. I may survive, or I may not survive.

I was talking to my kids – they’re adults now – and for them it was like, Death, what’s that? We are pushing death out of our heads. As if death does not exist. People are dying in the hospitals, they are not dying at home. In many ways it’s like cleaning our life from death.

We are shocked when someone is killed in a traffic accident, it’s like – Oh my God. And a lot of efforts are made to lower the number of people killed on the roads. I always think – is that because these deaths are happening in the public space? I believe it’s just as important to not allow so many people to die in hospitals. If you are dying in hospital, it is like pushing you out of society.

I think we also have to rethink the way we treat old people. Putting them in nursing homes is, of course, a form of comfort, but suddenly half of the home is dying because of a Covid outbreak. Of course, they will die anyway, but if it happened while they were living with their family, our relationship with the dying and death would be completely different.

My father died from cancer, and I remember that when he was in the hospital for the second time, he said: Son, please take me home. I want to die at home. And I took him home. It was painful for the whole family, but he was dying with us. And you know what the effect of that was? We didn't cry when he died because we knew he was free. At last the pain was gone – death was like freedom for him. Even my mom, who loved him very much – they were together for 50 years – was smiling. Because I said to her: Mom, dad died with you by his side, and now the angels will come and take his soul to heaven because he was the only man who could stand living with you for 50 years. She started to laugh.

I love the old Italian churches because they’re full of graves under the floor. When you’re walking down the aisle, it’s like walking upon memories.

If you’re asking me what we could learn from this pandemic, this would be one of the most important things. It’s very fashionable for a husband to assist his wife while she’s giving birth, but it’s also very important that we assist our loved ones in death. I hope that this more than a year now that we’ve spent living through the pandemic will have allowed us to not only watch a lot of Netflix, but also to ask questions of ourselves – about life as a whole.

Paweł Kowalewski with the gallerist Isy Brachot in his gallery in Brussels, Belgium, 1992

For many years you kept notebooks which later became inspiration for your artworks. Do you still continue this practice, and if yes, what kind of reality is being documented in them now? Do you think they will also eventually turn into artworks?

It is much more complicated. My wife was organising the house and about 90% of my notes were accidentally thrown away. So half of my life disappeared. I have started to restore it.

In Belgium I was represented by Isy Brachot. He had a big safe room for his private collection. Among other pieces, he also had sketches by René Magritte and other artists. Whenever I was there, I asked him to leave me alone in this room. When you’re just drawing, you’re not creating. When you are making notes with your pencils, you’re natural; you’re not acting. Sometimes a nerve or a twitch in your hand will cause you to make a mistake. You’re not an artist – you’re a human being. And I think this is what I love about sketches. In my collection I have a lot of things that are works on paper. For example, I have drawings by Italian artists Enzo Cucchi and Francesco Clemente, and I love to look at all these sketches, even watercolours. There is something very special there, very simple.

I strongly believe that often times these works on paper are even greater than paintings. Because when I am painting, there is always the chance to correct yourself; when drawing, that’s difficult. Of course, you can take a rubber and erase it, but there is a mark left from doing this. With a painting, you must make an X-ray to see it. There is a truth in drawing.

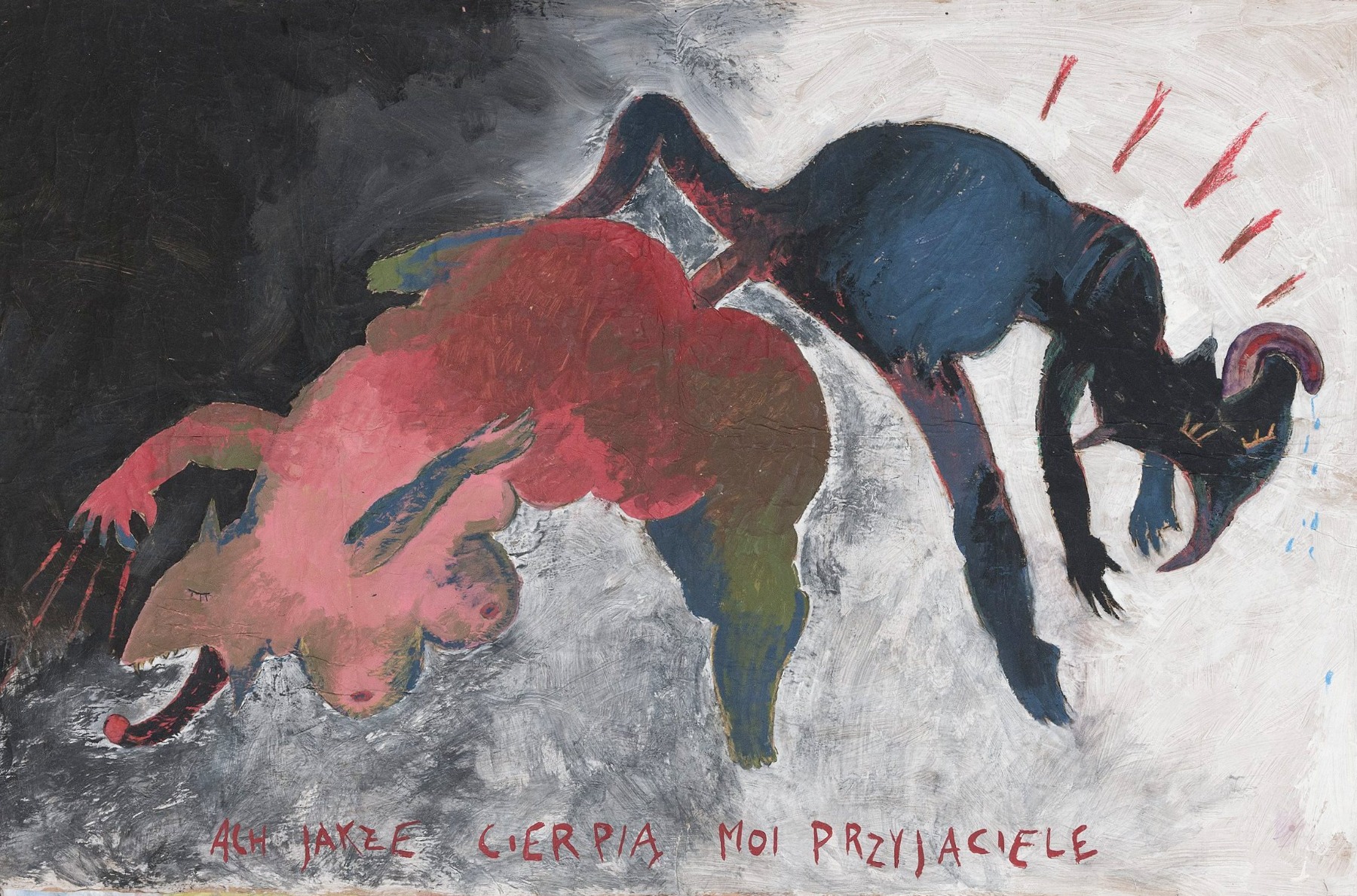

Paweł Kowalewski. Ah, how my friends suffer, 1985, distemper on paper, on deposit of the National Museum in Warsaw

Learning how to look is very difficult to teach to another person. What is your advice as an artist and as a collector as well? How do you look at an artwork? What are you searching for in it?

I don’t know how it was for you, but I was fascinated by art as a child. Like everyone at the beginning, I liked everything beautiful and simple. As I always laughingly say, we all started with Salvador Dalí. And then there comes a moment when you suddenly realise that the most important thing when looking at art is to ask questions and give in to feelings. What we understand and feel cannot always be expressed in words. When there’s something wrong in the picture, we instantly spot it, but this “mistake” is very often the goal, and it’s actually a great work.

If you’re asking me for advice – look carefully! I did a little trick with the large-format pictures at the Strength and Beauty exhibition; the stories of these ten women were written very, very lightly on transparent foil, and the viewer had to really concentrate to read them. Friends said to me: Oh, it’s very hard to read. My answer was: Because that is life; these are the lives of those ladies, and they were hard lives. Put on your glasses and go in closer to read it.

Unfortunately, our perception of art has become very consumerist, and we are at risk of losing a lot if we are not careful. If you truly want to experience art, in its very essence, it should be done in the manner of one object, one person. Not listening to anyone else, just yourself, and carefully looking. Even if you don’t like a particular work and consider it to be bad art, if you are careful, you can see much more. Sometimes art is stupid; not all artists are clever. But sometimes even with stupidity there is something charming and strange, and maybe even very sensitive.

Paweł Kowalewski. A strange friendship in the Swabian Alps, 1988, oil on canvas, 120 x 160 cm, private collection

Do you think that when someone is looking at your painting or another work of yours, there is a possibility that they are experiencing the same feeling that you had when you created it, even if just for a moment?

I hope that could be true, but it’s probably not. You know, this is the power of art – when we look at an artwork, we – all of us – see our own experience. We see our own dreams, joys, pride, etc.

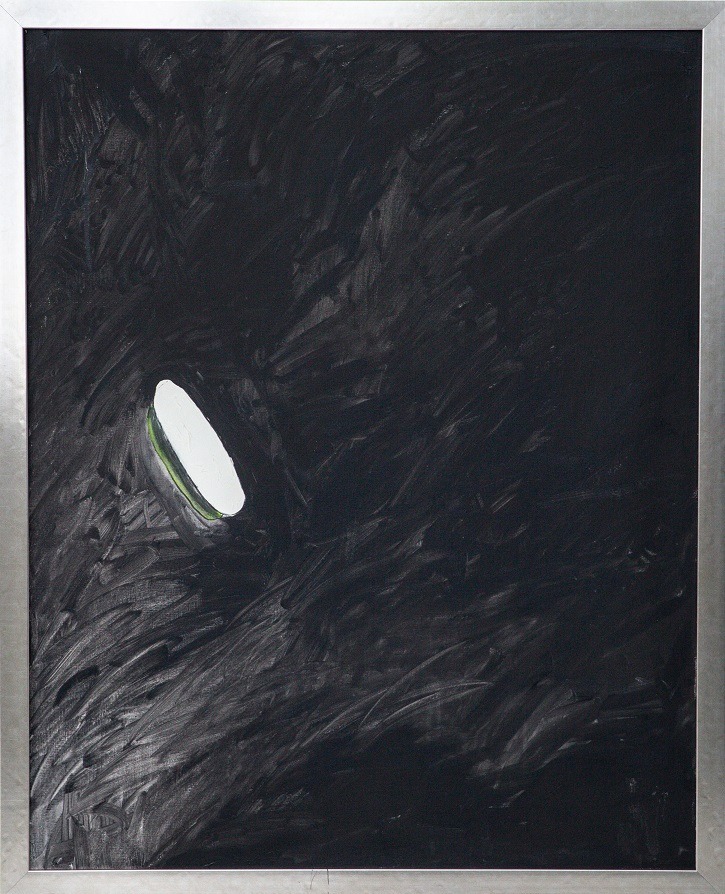

I recently painted a simple picture called Painkiller. It’s a white tablet on a dark, very expressive background. As you can imagine, all of the rich people, the businessmen, they love this picture. It’s ugly, but all of them feel something towards it. Probably because they see themselves in it.

As an artist, I can say what I want, but each person who looks at my work sees a different story.

Paweł Kowalewski. Painkiller, 2019, oil on canvas, 100 x 80 cm

Why do you, as an artist, have this need to be surrounded by the works of other artists? Why do you collect them?

I love to be surrounded by my art, but that’s a bit shameful [laughs]. I love art. My office is full of art. And I think that from the moment I started to put art on the walls, people have started to act differently. It’s like part of an educational process, and I love to educate people.

The one thing we are doing wrong – both artists and art critics – is that we are so happy with ourselves. We are so happy in this ivory tower of ours: Wow, we are geniuses and we just love each other. We don’t care about those rich idiots who do not understand anything… Believe it or not, but I’ve made collectors out of people you’d never expect. They all started from this Salvador Dalí thing, and then they just jumped to more and more difficult art. For me, that’s a part of my success; I see that they understand something, and that they are better people for it. They’re not talking only about Ferrari’s – there’s nothing bad about having a Ferrari – but now at least they have greater aspirations.

For me, art is my comfort zone. To be surrounded by good pictures is like being surrounded by good company. I am always asking and begging museum directors to leave me alone in the museum. I love to be alone, just sitting and being surrounded only by pictures. This is like a perverse pleasure for me. I think the most important thing to understand is that the really good pieces or artworks cannot be bought. We can only borrow them from time, because our lives are too short to own it.

Paweł Kowalewski at his exhibition „Zeitgeist” in Jerke Museum, Germany, 2017

You know, I have a soft spot for people who steal art because I understand that you can really experience a very tense need to have it. Sometimes you just want it so much... I have never stolen anything in my life, but believe me, if somebody left me alone with a picture I really wanted and said: You can steal it, I would steal it. Because this is something that is stronger than me.

I even understand those sheikhs and rich Japanese businessmen who keep rare pictures in their safes and just sit alone with them. I would probably never do that, but I understand why they do.

Empty rooms without pictures frighten me. It's like a life without any emotions. I can't imagine it. This is why I do what I do.

Title image: Paweł Kowalewski. Golden Boys, 2018, 24 carat gold, plaster cast. Photo: A.Świetlik