Doing art has helped me make sense of the world we live in

An interview with Swiss-Haitian artist Sasha Huber

At the start of the year, one of Rotterdam’s most respectable institutions of contemporary art, formerly known as the Witte de With Center for Contemporary Art (FKAWDW), changed its name to Kustinstituut Melly, thereby resolving the indirect, albeit obvious, shadow of colonialism that had hovered over its identity. This is the first precedent of its kind in the context of contemporary art institutions, and it began three years ago when a group of local artists and other activists issued an open letter calling for the name change process to begin. The art centre had originally taken its name from a street in Rotterdam dedicated in 1871 to Mr. De With, a Dutch naval officer involved in Europe’s colonial and economic expansion of the 17th century, and the activists’ argument was the inherent contradiction in the institution’s name – a centre that promoted freedom of thought and accessibility was living under the name of someone deeply involved with the racist and colonial past. Under its freshly appointed new director, Sofia Hernandez Chong Cuy, the art centre decided to act upon the request with a very radical, top-to-bottom name change initiative by resetting not only the name but also what the centre is, what it stands for, and who it caters to. All aspects of the centre’s programming, identity and mission were reassessed in order to create a meaningful and lasting institutional transformation.

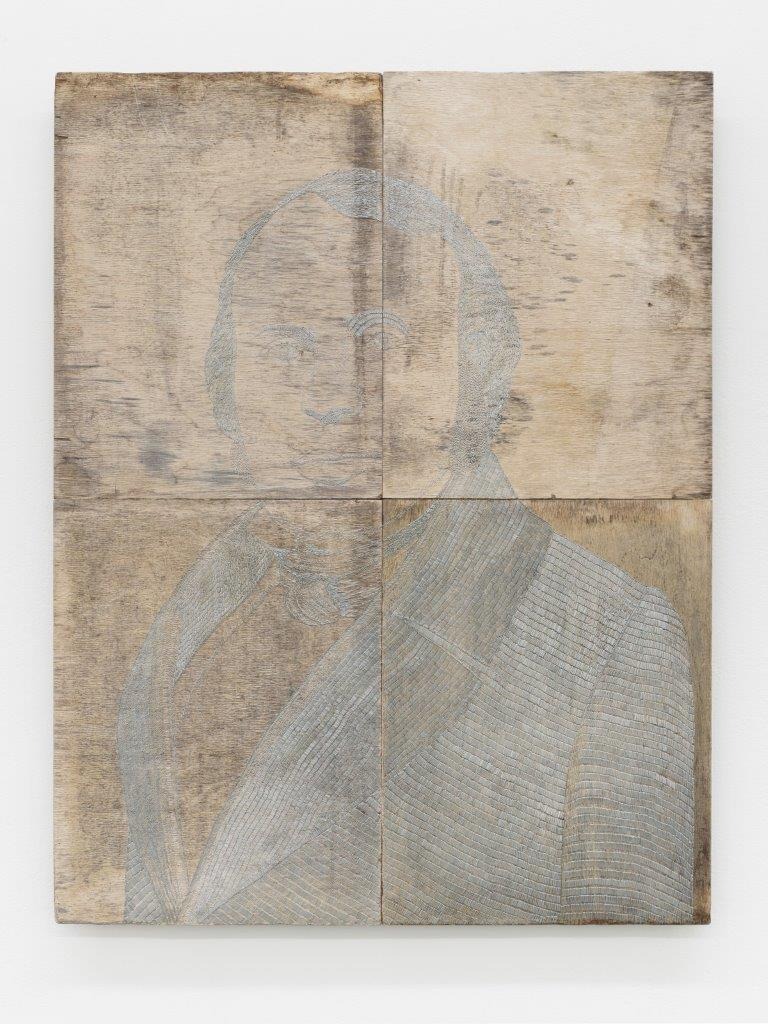

Sasha Huber, The Firsts: Matthew Henson, 2020, metal staples on fire-burned birch wood, courtesy the

artist. Exhibition overview Sasha Huber, a solo exhibition at Kunstinstituut Melly, Rotterdam, 2021.

Photo: Kristien Daem

The new name of the institution – Kunstinstituut Melly – was taken from from an artwork that was installed on the side of the building when it opened in 1990. Created by Canadian artist Ken Lum and titled Melly Shum Hates Her Job, the work has generated a veritable urban cult around itself in both the Netherlands and beyond. Melly (a real person living in Canada who loves the name change initiative!) is a very normal, working-class ‘anti-hero’ – so very representative of the public that the institution serves. This name was chosen as a bold, unique name that maintains the memory of the renaming process and the community-led transformation that the institution has undertaken.

The name change process involved the assembling of a Name Change Advisory Committee and the taking on of new board members who are more socially and racially representative of the public living in the area surrounding the centre. Staff were retrained, new team members were taken on, and a lengthy process involving research and the rethinking of their entire programming was undergone; even individual floors and spaces were renamed. Along with the name change, the institution’s entire working culture and artistic vision have been transformed in order to ensure accountability and to promote anti-racism, top to bottom.

Sasha Huber (b. 1975), a visual artist of Swiss-Haitian heritage who currently lives and works in Helsinki, was a member of the Name Change Advisory Committee. Her work is primarily concerned with history’s influence on the present and focuses mainly on the ramifications of colonialism. She’s sensitive to the subtle threads that connect historical attitudes to modern outlooks, and works with performance-based interventions, video, photography, publications, graphic design and archival materials. Her projects conceive of natural spaces – mountains, lakes, rock formations, glaciers, forests, and craters – as contested territories, highlighting the ways in which history is imprinted onto the landscape through acts of remembrance.

Huber has had a solo exhibition at the Hasselblad Foundation in Gothenburg, Sweden, and has participated in numerous international exhibitions, including the 56th Venice Biennale, Italy (2015); the 19th Biennale of Sydney, Australia (2014); the 29th São Paulo Biennial, Brazil (2010), and the Riga International Biennial of Contemporary Art (RIBOCA, 2018). Huber also works in a creative partnership with artist Petri Saarikko. In 2011 they initiated the long-term project Remedies Universe, which explores oral family knowledge in various geographical and cultural contexts. The duo has been invited to artist residencies located around the world, including New Zealand, Haiti and Tasmania. Huber edited the book Rentyhorn (2010), and was co-editor (with Maria P.T. Machado) of (T)races of Louis Agassiz: Photography, Body and Science, Yesterday and Today (2010).

Through 12 September, Kunstinstituut Melly is hosting Sasha Huber's solo show presenting over a decade’s worth of work prompted by the cultural and political activist campaign Demounting Louis Agassiz. Founded in 2007 by Swiss historian Hans Fässler, the campaign seeks to make public the racist legacy of Swiss-born naturalist and glaciologist Louis Agassiz (1807–1873). As a member of the Demounting Committee, Huber has staged numerous interventions at terrestrial and extraterrestrial sites bearing Agassiz’s name. The artist draws from both archival research and the embodied experience of moving through a world marked by the names of racist thinkers and policymakers, and in doing so seeks to make public the racist legacy of Louis Agassiz. On a practical level, this has entailed the artist’s involvement in local politics, lobbying, and petitioning for the renaming of these sites. On an aesthetic level, Huber explores art’s potential for engendering such sites’ symbolic re-dedication, effectively writing into being counter histories through movement, sound, and touch.

Sasha Huber, Agassiz: The Mixed Traces Series, 2010—2017, pigment on paper, courtesy the artist.

Exhibition overview Sasha Huber, a solo exhibition at Kunstinstituut Melly, Rotterdam, 2021. Photo:

Kristien Daem

Up until now, Kunstinstituut Melly (formerly known as the Witte de With Center for Contemporary Art) is the world’s only art institution in the contemporary art field to have undergone a renaming process of this type. What could this mean for the rest of the art world in the near future?

It’s been interesting to follow the process, and it was special to be on the Name Change Advisory Committee as well. As we know, Kunstinstituut Melly was formerly named after Admiral Witte de With, who led many colonial expeditions in the 17th century. The reason why the institution had the name in the first place was because it is located on a street with the same name. So it’s quite straightforward. Although this name change is perhaps without precedent in the art world, a similar changes are taking place with individual universities, and schools and geographical place names in other areas of the world. I hope the example of Kunstinstituut Melly will have an inspiring effect because if you start to scratch any surface, colonialism comes very often to the surface, and especially in the older art museums and cultural institutions. For instance, in terms of how the museum collections have been built, what were the reasons for the start of the collection, and so on.

And, of course, it will be interesting to see what the impact will be in the long run. That’s because the name change is not just symbolic – structurally, it was a chance to look deeper and see what can be done differently. So I hope it has an inspirational effect in that sense – as a kind of role model.

Sasha Huber, Shooting Back Louis Agassiz (1807-1873), 2008, metal staples shot into abandoned wooden

boards, courtesy of Museum of Contemporary Art Kiasma Collections; Agassiz: The Mixed Traces Series,

2010—2017, pigment on paper, courtesy the artist. Exhibition overview Sasha Huber, a solo exhibition at

Kunstinstituut Melly, Rotterdam, 2021. Photo: Kristien Daem

The renaming of Kunstinstituut Melly is the second project you’ve participated in concerning renaming. The first was the transatlantic cultural-activist campaign Demounting Louis Agassiz, which advocated the renaming of the Agassizhorn mountain in the Swiss Alps. Your over a decade-long work on this project is also featured in your solo exhibition at Kunstinstituut Melly. Based on your experience, how do you think art can contribute to healing the wounds inflicted by colonialism?

I was invited to be part of the transatlantic committee called Demounting Louis Agassiz, which had the goal of renaming Agassizhorn as Rentyhorn, in honour of the Congolese-born American enslaved man named Renty as well as others who experienced similar fates. This idea came about thanks to historian and activist Hans Fässler, who in 2005 wrote an important book about Swiss involvement in slavery and the slave trade (Reise in Schwarz-Weiss. Schweizer Ortstermine in Sachen Sklaverei); it was only the third book about these issues to have been published in Switzerland at the time. When the Louis Agassiz centennial was celebrated in 2007 (he was born in 1807), many exhibitions took place, but none showed the whole story of Agassiz.

Louis Agassiz was a Swiss-born naturalist, glaciologist and racist known for being a proponent of the ice age theory and research on fossils, and fish. In 1846 he was invited to the US by Harvard University to lead a lecture series, and he decided to stay there. Agassiz founded and became the first director of the Museum of Comparative Zoology. He had much more contact with black-skinned people in America than he ever did in Switzerland. It was when he came in contact with black people such as with those who served him, for instance. During this time he become an influential racist, going so far as to using photography (a medium that had just recently been invented in 1839) to photograph enslaved people. In 1850 he commissioned a series to be made of seven enslaved people; he then tried to use these photographs as the means with which “to prove the inferiority of the black race”. Renty was one of the slaves which Agassiz ordered to be photographed on a South Carolina plantation.

Agassiz was also a polygenist, declaring that there was a plurality of origins of the human races, that these different races were completely and genetically distinct, and that slavery was a natural condition for an inferior race. This unsavoury part of Agassiz’s story was basically left out, and in order to bring attention to this fact, we began the campaign to rename the Agassizhorn (3946 m) mountain. The international petition we addressed to the Swiss government and its two chambers of parliament was put on-line. The aim of the campaign was to collect signatures in support of renaming the mountain. Interestingly, Agassiz and his colleagues were the ones who actually named the mountain after him. Around the world there are over 80 places named after him, even on the Moon and on Mars. And then there are seven animal species, too. He has really colonised the whole world, I would say, and for me, that was the first time I engaged in this kind of renaming campaign.

I am part of the committee consisting of about 20 people from different areas around the world. I really took it seriously, and felt compelled to do something more than just write letters and wait. Actually, I decided to go up to the mountain and I renamed it physically – with a new sign and so on. Creating these images of this action has helped it all become real; I think that’s the power of doing art. You can imagine freely what you want, how you wish the world (or whatever you’re dealing with) to be, and it then becomes possible. You can renegotiate history in that way as well. I found that by making these, as I call them – reparative interventions, there really is the possibility of interfering in the history that has happened and that still has such a strong impact on our lives. I also see it as a possibility to not just accept it as it is, but to take an active position.

As part of the Rentyhorn art project in 2008, and as part of it, I started the petition website www.rentyhorn.ch to allow people who support the renaming idea to sign their names, and also leave a message if they want to. People are still signing it today (because the renaming has not happened officially), and it’s quite an interesting archive of comments that has grown over the years. The website really helped to broaden the project out. For example, four years later, in 2012, we were contacted by a the descendant of Renty, a great-great-great-granddaughter Tamara Lanier, who offered her support to help the project in any way she could. At that moment I understood that there was a deeper meaning behind this all, because through this project we had created something that contributed to the slow healing process. And not just in terms of Renty’s family. By honouring Renty, this initiative also stands for other people that have had similar fates. That was very powerful, and I’ve been in touch with lady Lanier ever since.

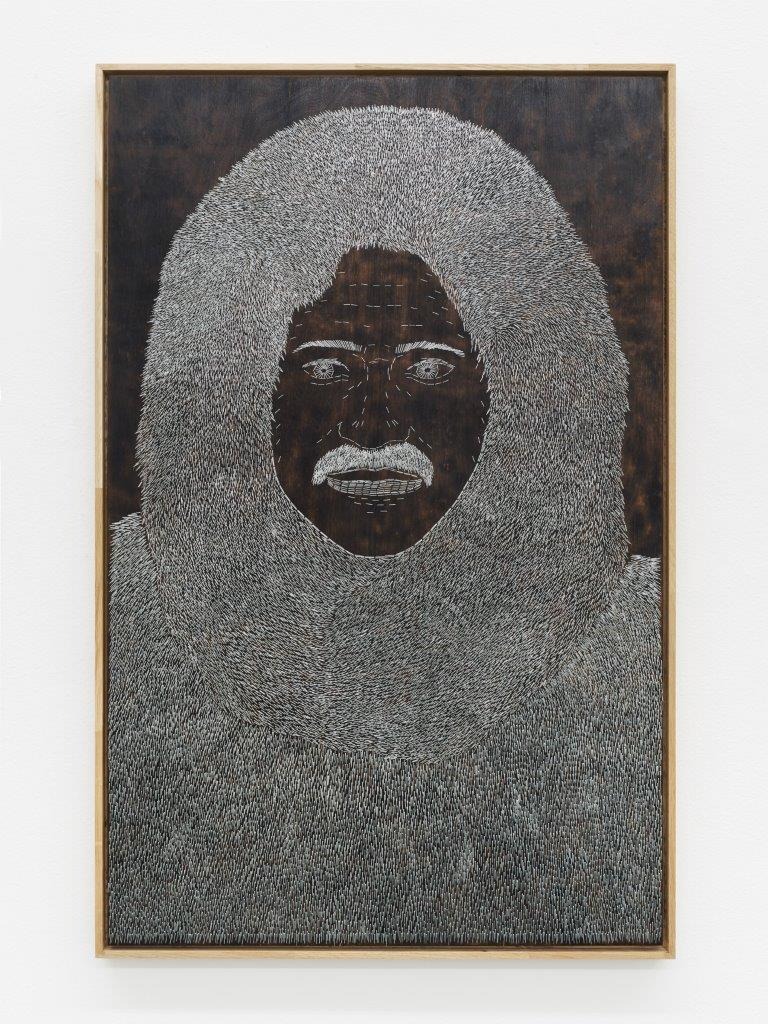

Sasha Huber, Shooting Back Louis Agassiz (1807-1873), 2008, metal staples shot into abandoned wooden

boards, courtesy of Museum of Contemporary Art Kiasma Collections. Exhibition overview Sasha Huber, a

solo exhibition at Kunstinstituut Melly, Rotterdam, 2021. Photo: Kristien Daem

As part of your exhibition tour, you are setting out to make an intervention at the Agassiz Ice Cap glacier on Ellesmere Island in Nunavut – which at 21,000 km2 is one of the largest in Canada – in collaboration with Inuit throat singers Cynthia Pitsiulak and Charlotte Quamaniq. Could you say some more about this project?

Ever since the first project, I’ve continued on to other countries – Brazil, and then New Zealand, where I was able to collaborate with the indigenous people for the first time, which was very important for me. In New Zealand there are also two places named by Agassiz, one of which is a glacier in the South Island. I went there together with greenstone carver Jeff Mahuika, and he performed a karakia there – a blessing to symbolically help un-name the glacier and free it of its association with Agassiz and his racism.

In Canada there are over 15 places named after Agassiz, one of which is the ice-cap glacier in Nunavut, found up north on Ellesmere Island. It’s very near the North Pole. actually, and it still is one of the biggest glaciers. During my first residency in Canada at Axeneo7 in Gatineau in 2017 I got to know Cynthia and Charlotte, the throat singers from Nunavut, and we made a video together called Mother Throat (2017) which I filmed at the Lac Agassiz (300 km North of Ottawa). I was interested to plan a intervention there as well at some point. When I was commissioned a new work as part of my solo exhibition produced by The Power Plant Contemporary Art Gallery in Toronto, I decided to work on this project. The plan was to go there in 2020, but due to the global pandemic this plan was already twice postponed. This delay allows me however to develop the work further in dialogue with the community. We hope that it will be possible to travel in May 2022.

Our plan now is to do a work similar to the one I did in New Zealand together with Jeff Mahuika, that is, go to Nunavut, walk to the glacier and sing, thereby symbolically freeing the place and bringing it back to its original state. This was supposed to happen last spring, but because of the pandemic it was not possible. Now we’re hoping to do it next spring because the time window is limited. To go there throughout the year is difficult due to the climate – the snow has to be in a certain condition, as well as the light and everything.

Sasha Huber, The Firsts: Matthew Henson, 2020, metal staples on fire-burned birch wood, courtesy the

artist. Exhibition overview Sasha Huber, a solo exhibition at Kunstinstituut Melly, Rotterdam, 2021.

Photo: Kristien Daem

Turning to yourself and your own story, how has your Swiss-Haitian identity affected your artistic work? Does your Haitian part somehow inspire the way you look at the world, how you create?

My Haitian heritage was in a way actually the starting point of my practice. My background is in graphic design as I didn’t think about studying art, even though I come from a family of artists on my mothers side. My mother and two of my aunts were painters and their father, my grandfather Georges Remponeau (they’re from Haiti) was a known self-taught painter, and he was one of the co-founders of the Le Centre d’Art art school in Port au Prince. It was founded in 1944 and still exists. So I was definitely exposed to the arts from Haiti, but somehow I chose the design path for the start.

My family immigrated to New York in the 1960s because of the dictatorship in Haiti, but I still do have family in Haiti. I was there with them when I was nine years old, in the late 1980s. I always felt very close to our family over there and I was keen to visit them again, but my mother never let me go back because of the political situation when I was younger. It doesn’t have to be, but, unfortunately, it can be dangerous. So there were valid reasons for not going back, but I was still upset that I couldn’t go. This made me start studying the history of the area – asking questions why is it like that, and so on. It all kind of came together in one moment, when I was doing my M.A. in Visual Culture at the University of Art and Design in Helsinki (nowadays Aalto University) in the early 2000s. I don’t remember how, but I came up with the idea of working with an pneumatic staple gun, which is often used in the construction industry when installing flooring. I tried it out and realised that it’s like a weapon. You have to protect your ears and eyes, and the weight of the staple gun itself is similar to that of a handgun. I suddenly had this idea of portraying some of the people that were responsible for the troubles in Haiti. This is how the project Shooting Back Series – Reflections on Haitian Roots (2004) came about. In these series of portraits I used thousands of metal staples to create images of Christopher Columbus, the Haitian dictators François “Papa Doc” Duvalier and his son, Jean-Claude “Baby Doc” Duvalier. The staples gave the portraits a metallic quality, similar to the effect present in western religious icon paintings. By selecting staples as a creative artist tool, I used the metal quality of the pins to symbolise the violence and destruction rendered on the landscape and people of Haiti. In a way, I transformed the staple into a memorial for the millions of lives lost during the colonial conquest of the Caribbean as well as the suppression of the Haitian people under the dictatorships of the Duvaliers. Shooting Back had kind of a double meaning – conjuring up the physical act of returning fire at the source of domination, and the notion that, within the creative space of visual art production, enslaved and indigenous people are capable of occupying a space of resistance against the oppression enacted upon them.

So yeah, Haiti has definitely been an inspiration and I always say that the Shooting Back project was like a seed that I planted from which everything else started to grow and broaden out even more.

Sasha Huber, Prototype, 2013, wood, courtesy of the artist and Petri Saarikko; My Racism is a

Humanism, a lecture, 2013, video, 29”00, courtesy of the artist; Rentyhorn (Letters of Request), 2008-2021,

printed correspondence, courtesy of Museum of Contemporary Art Kiasma Collections. Exhibition overview

Sasha Huber, a solo exhibition at Kunstinstituut Melly, Rotterdam, 2021. Photo: Kristien Daem

This is what you actually said in one of your previous interviews as well, that your methodology evolved from “shooting back” to “stitching up colonial wounds”. Could you elaborate on that in more detail?

At the beginning when I made the Shooting Back portraits I used so much energy to create these quite impressive portraits of historical men who have inflicted violence and who have been written down in history books so many times already, and so I decided to stop making portraits of these kinds of figures. The portrait of Louis Agassiz was the last in the series of portraits made as part of this attempt to “shoot back”. After I began to focus on telling the stories of those who were silenced in the history that we’re commonly told and who have been negatively affected by colonialism and imperialism. It felt much more empowering to me to create images in this same way, as well as feeling the pain – I call the works “pain-things”. – and people often ask what they are because they look like three-dimensional sculptures. I realised that they are “pain-tings”. Because I have to do it myself. I cannot outsource the pain that it relates to, and which is much about memory and the commemoration of people and situations.

Sasha Huber, Prototype, 2013, wood, courtesy of the artist and Petri Saarikko; Rentyhorn, 2008,

video, 4”30, courtesy the artist and the Museum of Contemporary Art Kiasma Collections; Karakia - The

Resetting Ceremony, 2015, video, 5”20 courtesy the artist; Mother Throat, 2017-19, video, 10”30, courtesy

the artist; Rentyhorn (Letters of Request), 2008-2021, printed correspondence, courtesy of Museum of

Contemporary Art Kiasma Collections. Exhibition overview Sasha Huber, a solo exhibition at Kunstinstituut

Melly, Rotterdam, 2021. Photo: Kristien Daem

When looking at your projects, one can see that they really can change things and make an impact. But when looking at the global art scene in general, how strong is the voice of art in these challenging times, and does art have the power to change anything?

Well, there are so many different ways of doing art and, you know, making art and also enjoying art. I think many people who are not aware or are not paying attention don’t necessarily always realise that art or culture in a myriad of different ways – be it music or anything visual, has a strong impact in their lives. There are so many different kinds of art directions and art forms. Impact-wise, I think the person who does art feels an impact even within a small circle. Even if it just makes someone happy to see a work of art, that is already a positive impact. I don’t think that an “I want to change the world” kind of goal needs to be a starting point. It can maybe evolve into something like that, as in when suddenly the work that was made literally takes on a life of its own by inspiring people and going on further and further. It is always beautiful when that kind of situation happens – when you couldn’t have anticipated it going in that direction. When you create an artwork, you let it out and you lose control; you don’t know what’s coming, or what will be made of it, or how it will inspire people or not. I have personally had several experiences that happened as part of projects that I couldn’t anticipate – they were serendipitous. I don’t call them coincidences; they’re like little miracles, somehow. And when they happen, I feel like: Okay, I’m on the right track and I have to continue this way. I have found my purpose in doing this, and it really encourages me to not only continue but also to share what I have learned with others. I’m very appreciative of the opportunity to speak to young artists and students, as well as giving talks or lectures, because it’s always inspiring to pass the stories on. It may inspire people to look around their own lives, because everybody has a story to tell. And it always has a value – it’s never less important just because not many people know about it. All these micro histories are so interesting, and I discover it also within my own family – I’m becoming the person who is asking the questions that usually are not asked. You know, when you’re just living side by side, you usually don’t ask certain things that relate to family history and so on. But if they are asked, stories come up that would otherwise stay untold. I especially think about the elders in our families that are slowly dying – they know so much and it’s so valuable. It’s something that can live on in us, and we can pass it on as well, not just to our children but also, as in my case, when you make an artwork or something that can be shared with anyone.

Sasha Huber, Evidence, 2013, ambrotypes, wet plate collodion photographs, courtesy the artist.

Exhibition overview Sasha Huber, a solo exhibition at Kunstinstituut Melly, Rotterdam, 2021. Photo:

Kristien Daem

Do you agree that – as the murder of George Floyd and the global reaction to it showed – the pandemic could be the impetus for addressing these long-standing racial issues that still persist in many places around the world?

I’m not sure if that’s just because of the pandemic. I think the pandemic has shown how marginalised and radicalised people have been much more vulnerable during this difficult time. The murder of George Floyd – which was very strongly communicated and which triggered the Black Lives Matter movement to spread on a world-wide scale despite the pandemic – was like a wake-up call. The urgency was so strong that people realised: Okay, now this is enough... we have to stand together and really take a stand. It was like a chain reaction, in a way. And still, similar incidents happen almost every day in the States and also in Europe, and other parts of the world. And even though many of these tragic incidences are filmed, which one should think is enough evidence, it still takes a lot to achieve justice for many of the cases.

The many protests showed solidarity, but in the meantime, structural racism continues to be a problem everywhere in the world. It’s good that this specific case ended in achieving justice, but unfortunately, but there are already new victims and other incidents happening. It’s kind of a never-ending story, and people are really tired and exhausted by it. You know, many white people have become more alert about understanding how urgent the situation is, but I am worried that people only feel it’s urgent when it’s really fresh. And then after a while, people don’t talk so much about it anymore because it’s not trending or not in the news anymore. So, yeah, let’s see how this develops.

Sasha Huber, Rentyhorn (Letters of Request), 2008-2021, printed correspondence, courtesy of Museum

of Contemporary Art Kiasma Collections; My Racism is a Humanism, a lecture, 2013, video, 29”00, courtesy

of the artist. Exhibition overview Sasha Huber, a solo exhibition at Kunstinstituut Melly, Rotterdam, 2021.

Photo: Kristien Daem

If we look at this pandemic as an opportunity to re-evaluate/question our attitude towards the things we are used to (our models of existing), as well as our plans for how we are going to live in the future, what are the main lessons the art world could learn from this crisis?

I think that art has definitely been a kind of rescuing entity that has helped people get through this whole situation to some extent. Like listening to music and all the creative things that people started to do. What I felt was a good thing to came out of this was that there were more online artist talks, lectures, and conferences and so on which were all held online. Of course, there was an overload at some point, but I it showed that it is a way to connect and exchange more widely and in this way become more accessible as well. I learned a lot during this year because usually many things are more local, but then there was also a sense of being all over the world at the same time.

Before the pandemic started, I had been travelling a lot – almost every month, and then it just stopped. And I was actually a bit relieved, too, because I was in this rush and I couldn’t stop it. So it helped me to recalibrate and rethink things. Maybe this will change the way travelling is going to be planned in the art world in the future. Of course, now we will maybe travel less, yet we won’t completely stop because we still have to continue to do what we need to do.

Have you managed to find out who you are? What does it mean to be human and alive? Can one find the answer to this most important question through art?

Doing art has helped me, personally, to make sense of the world we live in, and it has also helped me make sense of who I am as a person, where I come from, and who came before me. So in that sense, for me, making art is really about gaining some sort of understanding of the world – in a very visual and sonic way. I am inspired by the history that happened in the past and how it impacts our present, and also what the future could look like. I think that as an artist, one has the opportunity to look into the future and imagine it how one wants it to be. I think that the power to make ideas visible embodies the prospect for them becoming real.

Thank you!

Title image - Sasha Huber. Photo: Kai Kuusisto