Drawing can be whatever you want it to be

An interview with Ilga Leimanis, Canadian-born visual artist, educator and researcher

Ilga Leimanis is a Canadian-born visual artist, educator, researcher, and author based in London. Ilga’s practice-led pedagogy has brought her into contact with many students in the UK and internationally. An Associate Lecturer at University of the Arts London since 2015, she facilitates workshops in sketching and idea generation for UAL-wide Academic Support. She began teaching drawing as a short course tutor at Central Saint Martins, and has taught in many architecture and engineering offices in London since 2006. Ilga is a founder of the monthly drawing group Drawn in London (2007) and the author of Sketching Perspective, published by the Crowood Press (2021).

Ilga completed a Postgraduate Certificate Academic Practice in Art, Design and Communication (PgCert) at UAL (2022), earning a Fellowship of the Higher Education Academy, and continues studies on an MA in Academic Practice.

Her art practice is often collaborative and features drawing, collage, installation, and walking. She is a member of Five Years, an artist-run organisation, and contributes to its programming.

Your professional life has revolved around drawing and sketching. How would you describe their power?

Drawing can be used to visualize your thoughts; in that sense, it does hold a certain power. It can be used to see things in a different way, to get “out of your thoughts” and onto the paper. Once on paper, you can play and see something you had not seen before. It gives you an ability to make connections or associations with knowledge on an unconscious level.

Explain more about the unconscious level during the drawing process.

Over the course of the decade teaching and working with this method, I have experimented with the facilitation of the workshop by balancing my delivery between structure and openness. It needs to be open to interpretation and accessible, but there also needs to be a certain structure because there are students from different fields, for example, fine art students and design students who design furniture, fashion or ceramics, but also marketing students who work with business ideas. Some students are working with time-based media like film or animation; others are curating or developing exhibition design. I structure my workshops so they benefit a broad range of needs.

The core principle is that you are doing something; there is action, which is generative.

I start by asking participants to sketch on paper, and in that moment they become connected, something happens: a student recently said, “literally while you draw, you get more ideas.” The core principle is that you are doing something; there is action, which is generative. I see it as a two-part process: first, get something onto paper and keep sketching quickly, about 10–20 minutes, and aim for many sketches (as many as you can do, 20 or more). See these tentatively pushing into new directions. Play with your material, take a risk. Then, look at what you have, and “read” your image.

Play with your material, take a risk. Then, look at what you have, and “read” your image.

Student work, sketches from the Thinking Through Drawing workshop I facilitate since 2015 for UAL-Academic Support

I tell my students to take a risk and understand that everything you sketch will not necessarily lead you to a new idea; it is not a linear process. Push yourself into a new direction. Most of my students hope to generate ideas born out of complex research, but this method also works if the starting point is something simple and easy to understand, like a representational drawing. The moment of surprise is important; there is a lovely expression in English, the “happy accident”, which I have learned to embrace in my own art practice and as an educator: I try to be responsive, I learn to negotiate the fluid, I allow things to happen, and I enjoy the process.

I try to be responsive, I learn to negotiate the fluid, I allow things to happen, and I enjoy the process.

Can you give specific examples from your teaching experience?

During my workshops I encourage students to share what they have done. When it was her turn, one student said, “I think I did it wrong.” What she did was different to what others had done. I reassured her that it is not possible to make a mistake – my instruction was purposefully open to interpretation, and I do not offer a step-by-step guide: my role is to facilitate – I enable students to have agency, to interpret. This student explained that she had found a solution for a problem, resolving another project she was working on – an easy (even budget-friendly) solution which clicked in her brain during the “reading” process. These “happy accidents” are remarkable and repeat in most workshops if the students are open and ready to focus on the task at hand.

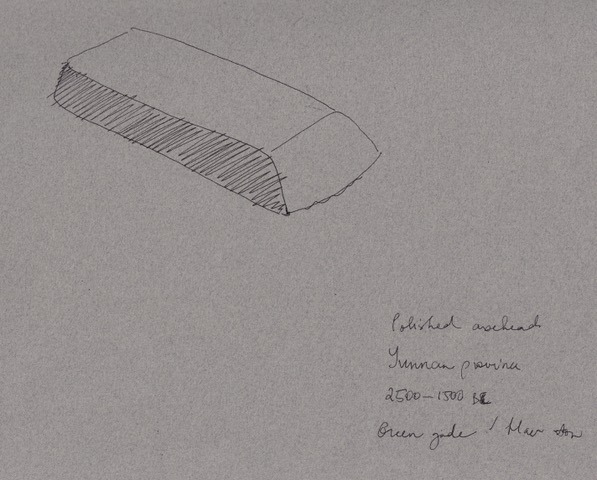

Years ago, I took my students to sketch the British Museum’s collection, on research days for idea generation. One student had drawn an ancient axe head in the Asia Gallery, a small object about the size of a mobile phone, but wedge-shaped with grooves like teeth for chopping. At the start of the next class, the student said, “I don’t know what to do”. I suggested he redraw his sketch in ink with brush. I love ink; its fluidity makes it faster than drawing with pencil. I use ink often in my own work. Another advantage: ink is permanent and you cannot go back – it requires a different mental state if you know you can’t erase your lines and start over. I told my student to redraw in ink and then repeat. He took that literally and repeated the same set of lines, the wedge, and the teeth, over and over probably about 50 times. At a certain moment, he was not thinking anymore about the axe head – his hand already knew what to do after so much repetition. Maybe that was the flow state? It was difficult to put into words. I realised that something had happened; he felt more powerful… perhaps this connects with your first question about the “power of drawing” – if you allow yourself to let go of what you think you want and just “let it happen”.

While working on a project recently, I found my old sketch, the recreation of that axe head which I used in demonstration.

My copy of a student’s sketch (c2009). The original was drawn from observation in the British Museum’s Asia Gallery – an axe head

Looking back, I think that was an important moment when I realized that my role is to get people to find this space, to help them access a flow state through sketching quickly; it led me to develop this method for idea generation.

How did you develop this teaching method?

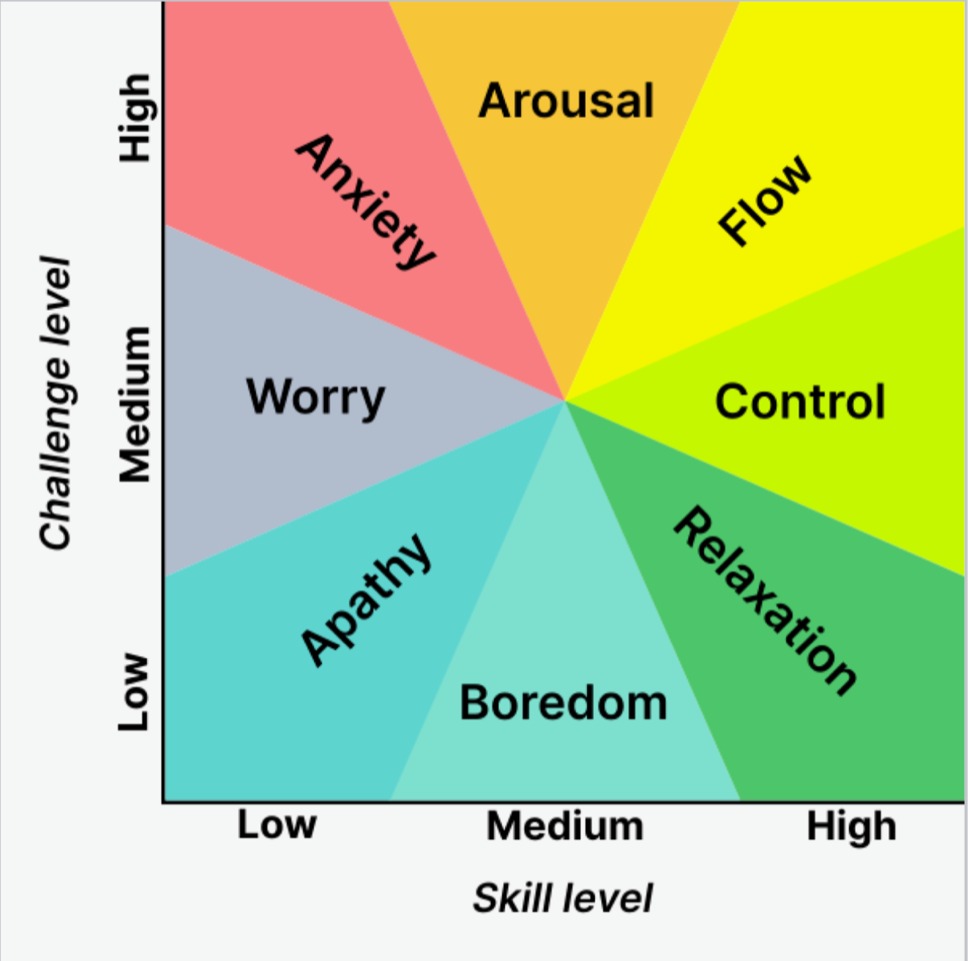

In the 1990s American-Hungarian psychologist Mihalyi Csikszentmihalyi published his research on “flow”[1], an optimal state of action when you are fully engaged in what you are doing. Csikszentmihalyi talks about certain characteristics needed to access the flow state. Rules and parameters, such as in games or sport, enable you to do that quite quickly because you get into that space and work fast. I discovered his theory a few years ago and felt it click with what I was doing. I show his diagram to my students to help them position the activity: on one axis are skills and on the other, challenge.

Mental state in terms of challenge level and skill level, according to Csikszentmihalyi’s flow model

Flow occurs when you have enough skill and challenge to feel fully engaged in what you are doing.

Flow occurs when you have enough skill and challenge to feel fully engaged in what you are doing. Most people have probably experienced flow at some point; characteristically, the passage of time is not noticed. The sketching method that I facilitate aims to help people access that flow state as quickly as possible, creating a domino effect – things start to happen as if automatically.

The sketching method that I facilitate aims to help people access that flow state as quickly as possible, creating a domino effect – things start to happen as if automatically.

Do you discuss these processes with your students?

I outline the process. For some people it is obvious – they immediately see something and can read an image, but for others it is more difficult. I talk about reading images without thinking, bringing an awareness to that process, asking yourself “what is this that I am doing” while looking at the drawing. Sometimes I say, “Pretend that somebody gave you this piece of paper”, look at it and try to make sense of it.

I talk about reading images without thinking, bringing an awareness to that process, asking yourself “what is this that I am doing” while looking at the drawing.

My furniture design students might need hundreds of variations of a design, for example, a chair. For them, it is obvious – they know what their design is, but others are working with various sources of research or more abstract theories, and can surprise themselves by using this method. The drawing or sketch becomes a tool that transports you into a different area, perhaps within your field of knowledge, but you had not been thinking in that direction.

The drawing or sketch becomes a tool that transports you into a different area, perhaps within your field of knowledge, but you had not been thinking in that direction.

Would you say there are different student types?

In teaching, I am always looking for exceptions or challenges. Most of the workshops I teach are short; I need to be effective in my communication to get my point across. There are the words I repeat like a script because I know they will work. I have tried perfecting that script and getting those words right, and now I can tell immediately if my words have not been understood or were not specific enough.

Last year I worked with one group at the Art Academy of Latvia. They were all working on the same social design project collaboratively. It was interesting to take the usual structure of my workshop, which helps students with their individual work, and amend it to fit a collective model working with a group.

I cannot speak to types of students, but rather different approaches to sketching. For example, some people will draw separate sketches, others will put everything into a frame – some students think “in frames” like filmmakers or painters, while others are not bothered with framing. There are some who add more details to their drawing, a maximalist approach, and then they try to make sense of an abstract mess. Order and control are frequent themes that come up in my groups for discussion – how to order the creative chaos or accept it.

Order and control are frequent themes that come up in my groups for discussion – how to order the creative chaos or accept it.

I know that you are a student now as well. What are you studying?

I believe in life-long learning and have learned so much from my students: they taught me how to teach through a practice-led approach. I am now interested to read about theories of education. I study at the University of the Arts London where, as a member of staff, I have a wonderful opportunity to develop my research. The PgCert is a postgraduate certificate in Art, Design and Communication, and this year I applied for Fellowship of the Higher Education Academy (FHEA). Currently I am a student on the Master’s in Academic Practice – I am researching my years of facilitating this method and using the experience I have gained while working with hundreds of students. Their anecdotal evidence, feedback and quotes are combined with theories like Csikszentmihalyi’s “flow”.

Is his theory the basis for your research?

Csikszentmihalyi was my starting point, but I also collaborated with my sister Andra Kalnins for an exhibition and action research project. We have been working together for a year now and developed sisters hope, which we exhibited at Five Years (2022).[2]

'sisters hope' installation view. Five Years, London, UK. 27 February 2022

Following a metastatic breast cancer diagnosis, Andra was keen to develop a personal project for her patient advocacy work. She asked me to run an idea-generation sketching workshop with her, which became the start of our weekly meetings. Our intention was to spend precious time together and follow where our conversations took us. Paying attention, noticing moments, elevating these to fill the distance. We discovered that Andra also has Csikszentmihalyi’s book on her shelf because she studied psychology at university and connected with flow through an interest in sport performance and mindfulness.

Last November, Andra suggested we attend a conference on “hope” where we were introduced to the work of Gwinn and Hellman[3], which became another valuable way for us to view our work. I think that “hope” also connects well with my idea generation workshop. On the most basic level, students come to the workshop with hope: they hope for a new idea or hope to do well on their project. I’ve started looking at my work through this lens and will be continuing research in this area.

I am sure you will create your own theory, a valuable contribution.

Yes, it is a part of my life I find the most exciting now. I am so grateful to have an opportunity to continue my studies and have access to tutors and great minds that push me forward.

You mentioned your sister and your collaborative project, which is related to her illness. How has art helped you both since her diagnosis?

I wanted to spend time with Andra – I was beginning to panic that we would not have enough time together. Our conversations became meaningful; we saw that doing, meeting and talking is action, and gives hope. Gwinn and Hellman mention in their book how a devastating diagnosis may increase hope and you can always re-evaluate pathways. Andra and I discovered that in adversity it is also possible to flourish. Hope is a social gift we give to each other; this has been a relationship of discovery. Art was an instrument in this process. We believe, as Gwinn and Hellman say, that hope moves to action; feelings of empowerment accompany this journey.

Andra talks about the transformative properties of art. Between treatments she finds herself looking at the art found in hospital hallways, and we have spoken about Walter Benjamin’s “aura”[4], in this context, the unique presence of a work of art in time and space.

What kind of inspiration helps you teach?

I find inspiration by looking at art and design; being curious about the world around me, I take advantage of the many galleries and museums on my doorstep. For historical and contemporary drawing, one of my favourite places is the British Museum’s Prints and Drawings Gallery, on the 4th floor at the back of the museum. I learn by looking and doing. For me, reading would follow looking.

I learn by looking and doing. For me, reading would follow looking.

Please say more about the beginnings of “idea generation” – did it develop from your drawing skills courses?

When I first moved to London, I started teaching drawing skills courses – at first working with professionals in architecture and engineering and then short courses at Central Saint Martins that are open to all (also known as adult or continuing education). Often these attract portfolio preparation students or people who want to learn how to draw. These short courses were a constant presence throughout the year and repeated many times, allowing me to learn on the job. I was able to test out new methods, and lucky to work with hundreds of people from all over the world. It was an exciting time.

Towards the end of these courses, I encouraged students to use their new observational skills on a project of their choice, but once you say to somebody, “You can do whatever you want”, they would suddenly not know what to do, or they would look at their phones for a photo to copy. I challenged them to get creative, and what I discovered was how to make that process easier. It pushed me to find methods to guide students to trust process.

Is it a purely practical course or is it also theoretical? Do you talk with students about philosophy? Do you ask students to read specific literature?

It is a practical course but there is also much discussion; many subjects are brought up by individual interest. I generally see students for a limited time – short courses of up to 25 hours or one single 3-hour session, as in the Thinking Through Drawing workshop.

Please talk about your own first experiences in learning how to draw.

I have always enjoyed drawing. I remember there was a drawing I made as a child, a portrait of my cousin Daina and I from a photograph, which I gave to my grandmother who framed it for her living room. I was 11 or 12 when I made it, and not a skilled drawer. I went to Dawson College (a post-secondary educational institution within Quebec’s network of CEGEPs) at 17, where I was introduced to a broad range of materials and methods (in addition to painting and drawing, we also had printmaking, sculpture, design, and art history). In my drawing class, one teacher brought in a glove she had picked up off the street, flattened by car tires, for us to draw. After the 1960s, skilled drawing was not in favour, and by the time I started studying art, a different approach was embedded: we were looking at the object and depicting it as we were feeling and seeing it, and research played a big part in the development of the work. It was a different system of education than, for example, in Latvia, where I arrived in 1992 to study at the Art Academy of Latvia. The Latvian drawing school was based on skills and a “correct way” of doing things, but in Canada there was no “right” or “wrong”. At first, I did not notice a difference, but during my first year in Latvia, my fellow students told me that I couldn’t draw. I didn’t understand the academic drawing tradition, as I had never encountered it before. I remember that feeling of disorientation, encountering an entirely new system, feeling it in my body, but I think this experience has made me a better educator, as I realised not everyone shares the same values. My Canadian school never emphasised a “right” or “wrong”, whereas there are rules in Latvian, Russian (or Chinese) traditions, studies of anatomy, etc., that go back to the 18th century French Academy.

Canadian school never emphasised a “right” or “wrong”, whereas there are rules in Latvian, Russian (or Chinese) traditions, studies of anatomy, etc., that go back to the 18th century French Academy.

When I studied at the Latvian Academy of Art, I had a place in the Monumental Painting Department with Indulis Zariņš and Aleksejs Naumovs. I was a fee-paying student and had to submit documents and a portfolio. Based on this submission, they put me straight into the 4th year (at the time, you had to study for six years). They took into consideration my two years at Dawson College and one year of a bachelor’s degree in Arts Plastiques (Fine Art) at the Université du Québec a Montréal, but I think the 4th year was comparatively freer than the first three, which were devoted to observational studies, for example, portrait, hands and feet, half-figure, drapery, etc. (I did not realise at the time that this allowed me to bypass the entrance exams, which I would not have passed.)

Initially I went only for one year, but I fell in love with the school, formed close friendships, and begged my parents to stay longer. I wanted to learn the academic tradition starting with the basics; I drew plaster casts, drapery, and learned about colour mixing the perfect grey. My private tutor, Kristaps Ģelzis, was one of three suggested drawing teachers and he taught me how to draw “properly”. It was difficult, but I am proud of the drawings I made at that time; I would not have the patience to do it again. To train my hand, Ģelzis set repetitive exercises – he asked me to use short hatching strokes to cover entire pages of my sketchbook a uniform grey. My sense of self had shifted – I thought I was a good student, but I did not have the basic skills as they were taught in this context.

Did this study help you to understand what is drawing?

At the time, I was desperate to learn how to draw. I worked hard, and it became a part of my identity. I wanted to be immersed in that environment. I wanted to better myself. I am grateful for the opportunity and I graduated from LMA in 1995.

I was desperate to learn how to draw. I worked hard, and it became a part of my identity.

Rooted In Limbo (2017) Five Years, London, UK installation view (detail)

Do you connect drawing with painting? Your solo exhibition in London extended the definition of drawing, did it not?

I think drawing can be whatever you want it to be, and it can start to merge with other disciplines. Contemporary drawing can be anything – it is wide open to interpretation. For example, you can draw with your feet by walking on the street – even if there is no trace, nothing physical to look at or touch, only the action remains. This reminds me of my friend Susan Stockwell’s work, where she “took a line for a walk” by dripping poster paint on the street. Her footsteps pulled this line, while somebody behind her filmed her drawing.[5]

Susan Stockwell, Taking a Line for a Walk, (2002) 12-minute film. https://vimeo.com/103926626

So, this means that drawing is much broader than just pen and paper?

Yes, and it ties back to my sketching workshop where there is no right or wrong. You can’t make a mistake. Withhold judgment about good or bad – perhaps something can become useful to you later.

Withhold judgment about good or bad – perhaps something can become useful to you later.

Tell me about your art practice. In addition to sketching and teaching, you also create artworks.

My recent series of drawings were attempts at visualising energy by using marks on paper, for example, MIDDplace[6], a collaboration that started just before Covid in January 2020. My friend Melissa Manfull, a Los Angeles-based artist, invited a small group of friends to collaborate on a mail art project: Melissa, Diyan Achjadi (Vancouver), me (London) and Doreen Wittenbols (Santa Fe). We studied together on the MA at Concordia University in Montreal. Melissa’s idea was that we each start a drawing proposing a spatial question open to interpretation. We mailed these drawings to each other in turn, not providing any instruction or information. When I received a drawing, I hung it on my wall and looked at it, turning it around and sketching ideas on separate papers, but it was hard. I was aware of the time others has spent drawing and did not want to ruin anything. This project was incredibly rewarding because it pushed me to be experimental and try new materials; I used chalk pastels for the first time and glitter, and I discovered weaving with paper, cutting into the drawing with scissors. This collaboration was an excellent problem-solving exercise.

MIDDplace – IDDM, 2022, mixed media on paper, 120 x 80 cm / MIDDplace is a long-distance, mail-based collaborative project between artists Diyan Achjadi, Ilga Leimanis, Melissa Manfull and Doreen Wittenbols. This is the first time that the four of us have come together in a collective effort to navigate drawing, making and thinking together across time and space. The works were exhibited at Elephant Art Space in Los Angeles in April 2022

Do you feel that there is a need to expand and create different organizations and unions for drawers to exchange their experience, communicate, and find new collaborations in this way?

I’ve always been interested in collaboration and sharing my experience is becoming more important to me. Usually this happens organically – simply talking to someone sparks an idea – but many great organisations devoted to drawing already exist. For example, when I first moved to London, I worked on the Big Draw launch events, amazing large-scale public drawing days in Spitalfields/Covent Garden (2007) and St Pancras (2008), and I was invited back to the Big Draw a few years ago to present my experience to other drawing professionals. Last year I spoke about teaching drawing in an online symposium organised by Drawing Projects UK, and I was one of a group of UAL staff researchers part of the RAS (Retain Achieve Succeed) programme. Together with my colleague Chris Koning we published a chapter about the skill of drawing and its link to creativity (through an intersectional lens). Our research cohort met on a regular basis led by Dr Kate Hatton, editor of the book Inclusion and Intersectionality in Visual Arts Education (2019).[7]

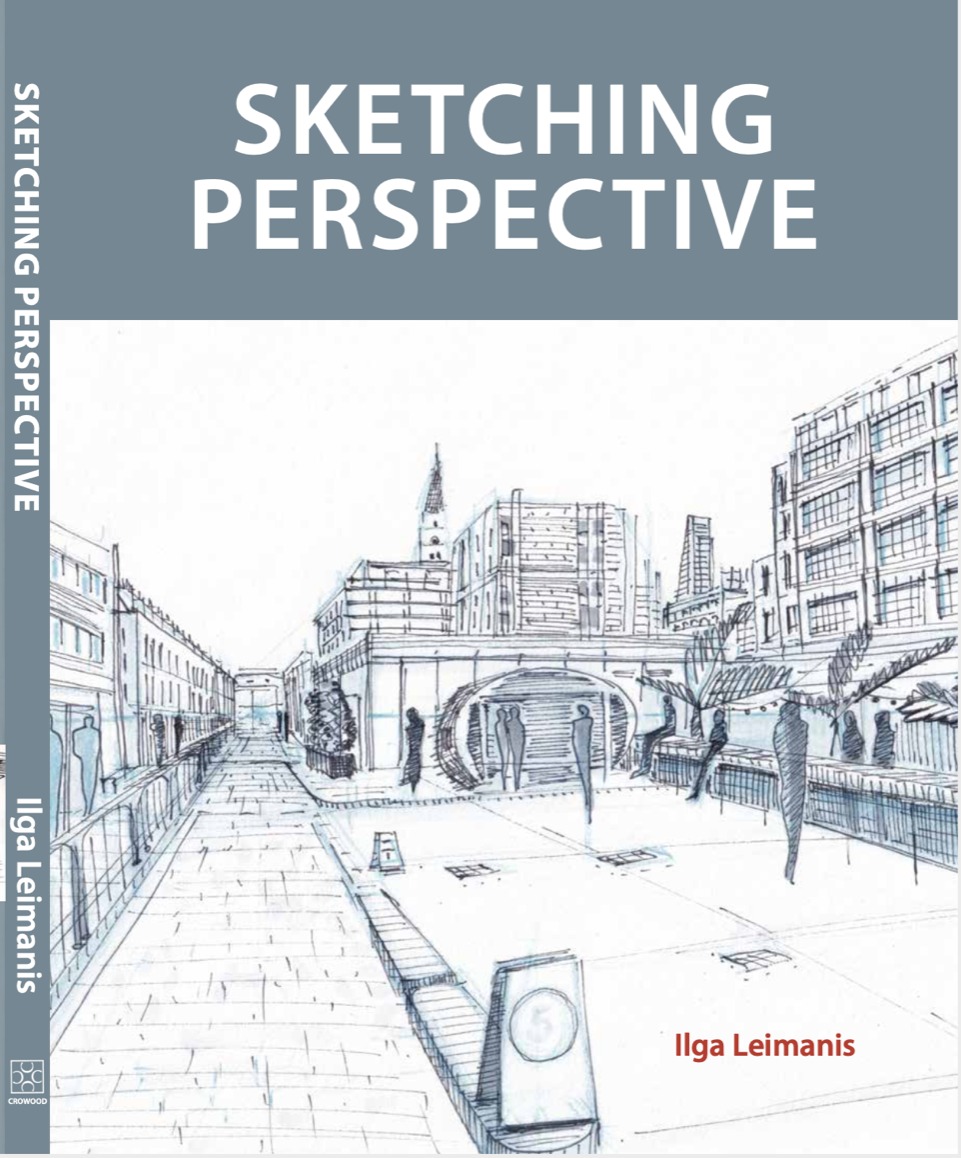

Another big project is your book Sketching Perspective. How did you get this offer?

I was approached by commissioning editor Rachel Allen from the Crowood Press – she said that as publishers of instructional books, they look for authors who teach their subject: teachers already have the words they use in instruction, the ‘scripts’ they have honed through years of teaching. In the beginning, I proposed to write a general drawing book, but after looking though my archive, I realized I have many city sketches. I taught perspective drawing and ran Drawn in London, a location-drawing group, for years and encountered many learners; I have examples for each type of problem. I decided to base the book on my urban sketching courses using these many sketches.

How did you feel during the writing process?

The book was an opportunity to share the wealth of experience I had gained teaching drawing skills – how to draw correctly from observation without frustration. Many students who had taken my courses said I should write a book and share my method. I knew how valuable this opportunity was, but the process itself was complicated. There was never a free moment to add this “job” into an already busy life, for example, my son was transitioning to a new school and that needed my attention. It took nearly three years to write the book, much longer than specified in the contract I signed, but luckily the publisher was patient. The structure was easy, the table of contents and a first draft, but once you start, you realise the job is much bigger than you thought! Now the book is published (May 2021) and I am grateful it has been well received with good reviews.

My first book Sketching Perspective published May 2021 by the Crowood Press

You said you have kept your demonstration sketches made during the last ten years, and you used these drawings when you were writing the book. How did this huge amount of work help you in creating Sketching Perspective?

Perhaps it is a question of time. Observational drawing can be labour intensive and time consuming if you don’t know what you are doing. I remember asking students, ‘How long did it take you to draw this?’ You can make a great drawing if you take the time, or perhaps your hand already knows what to do and you can do the same drawing quickly. Think about it when you next look at art: when you see something finished, it does not reveal much about process – often time and labour are hidden. My personal preference is for fast and easy, but to be fast you must understand what you are doing, or you need a method you can rely on to override your brain, which will try to trick you. For example, when you stand on a street and look at a building, the roofline will always be angled down because it is above you, but I have many students who draw it the opposite way – their mind tricks them. I am sure there is scientific data to explain this. You might not know how to draw academically, but I can teach you the skill of being able to check and correct your work quickly and without much effort.

When you see something finished, it does not reveal much about process – often time and labour are hidden. My personal preference is for fast and easy, but to be fast you must understand what you are doing, or you need a method you can rely on to override your brain, which will try to trick you.

To sketch is to communicate, and I’ve always demonstrated concepts in front of my students to explain how I see things. I kept these demonstration sketches because I wanted to develop my teaching: there were always new questions and I hoped to reach every person in my audience. I went through all these sketches and used them as examples in my book. Now, I post them on a new Instagram account where I share my drawing journey.

To sketch is to communicate, and I’ve always demonstrated concepts in front of my students to explain how I see things.

I have drawn in front of people now for a long time, but it was not easy at the start. I was shy and had to overcome feelings of not being good enough. Overall, it has been quite a transformation, and I realise that compassion makes me a good educator. I communicate the speed of sketching by doing it live in front of students. I also teach online (over six years now) and draw on camera – students can see my process and thinking in real time. I hope to inspire confidence, reveal that moment of connection with the paper in all its raw and messy state: saying it’s ok to let go of an impossible ideal of perfection.

Have you started to perceive art differently?

I feel more excited as an artist – after so many years in this field I feel new energy. I was speaking to a friend, and he noticed my excitement and he said that as artists, we forget and we take art for granted; we lose that sense of magic.

***

[1] Csikszentmihalyi M. (1997) Finding Flow: The Psychology of Engagement with Everyday Life, USA: Basic Books

[2] Kalnins, A. & Leimanis, I. (2022) sisters hope [Exhibition]. Five Years, London, UK. 26 February - 6 March 2022. / www.fiveyears.org.uk/archive2/pages/294/Sisters_Hope/294.html

[3] Gwinn C., Hellman C. (2018) Hope Rising: How the Science of Hope Can Change Your Life, New York: Morgan James Publishing

[4] Benjamin W. (2008) The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction, London: Penguin

[5] Stockwell S.,Taking a Line for a Walk, (2002)12 minute film, https://vimeo.com/103926626

[6] MIDDplace (2022) [Exhibition]. Elephant Art Space, Los Angeles, USA. 9-30 April 2022.

[7] Koning, C. & Leimanis, I. (2019) ‘Drawing as an Inclusive Practice’. In Hatton, K. (ed) Inclusion and Intersectionality in Visual Arts Education, London: UCL Institute of Education Press, pp. 99-121.