Not a gallery for art – a gallery for culture

An interview with Leopold Thun, Co-founder and Director of Emalin gallery

Leopold Thun and Angelina Volk from Emalin gallery remind me of Vita Zaman and Magnus Edensvard from the Ibid Projects – another set of young gallerists in East London some 15 years earlier. Both graduates of prestigious art schools – St Andrews in the case of the former and Goldsmiths in the latter – they set out unique and ambitious art programmes characterised by unexpected connections, fresh perspectives, and bold yet fun statements that channel the zeitgeist of their generation in a way that electrifies the imagination of many art lovers. Both are characterised by early success, too. Ibid Projects gallery in Hoxton Square became a hot spot for collectors like Rubell and Horst scouting for young talents from Eastern Europe and elsewhere. Emalin gallery, for its part, has been immensely successful in organising younger generation collectors in their Shoreditch space, and has landed a booth at both Art Basel and Frieze art fairs, a substantial recognition by an art establishment given the gallery’s mere six years of age. But what unites these young art professionals much more than the above facts is the fire in their eyes and an eagerness to bring people together around the art they believe in.

Installation view, Hand to your ear, Part I (presence/surplus), Emalin, London, 19 November 2021 – 22 January 2022

Courtesy of Emalin, London.

Photo: Stephen James

What does it mean to run a gallery with an art programme that doesn’t shy away from the political aspects of today’s contemporary world? The following interview with Leopold Thun took place in London on January 31 of this year.

The current situation in the world is very complex. Do you think a person can get a sense of what is going on in the contemporary world by visiting a show in your art gallery? Could seeing an exhibition perhaps provide some relief, some understanding? Moreover, what do you see as the role of contemporary art at the beginning of 2022? Has is changed compared to the pre-pandemic times?

I generally think that the world has always been complicated and complex. Maybe now we are more aware of it. Perhaps because of the way media works now, we become aware about things that were not considered relevant before. The role of art has always been the same and it hasn’t changed. On one side, it provides a form of escapism – one in which we can travel to unseen places, to past times, to the future: art really is a time machine. At the same time, art poetically points to specific things that are happening and it can provide a different lens to look at contemporary happenings. Sometimes art quite painfully makes you aware of things you were not aware of. Art always stands in relation to its surroundings – sometimes by denying its surroundings. Denial is a form of acknowledgement in some way, too.

I think the role of the gallery, too, has been left unchanged. We currently have a group show with six artists, and even though not all of the works immediately seem that they are about current matters, they are all obviously aware of what is happening, and I believe some of it finds its way into their work.

Alvaro Barrington. Splash em, 2021 / acrylic and oil on burlap in wooden artist's frame, steelpans, galvanised metal garbage lid

236 x 167 x 22 cm

© Alvaro Barrington

Courtesy of the artist and Emalin, London.

Photo: Stephen James

Speaking of art’s relationship with its surroundings, although you both come from places that have a strong tradition of art collecting – Angelina is from Germany, whereas you having been brought up in Switzerland and have an Austrian and Italian background – you have chosen London’s Shoreditch as the hub of your activity. Besides being a great place for commerce, is London also a centre of contemporary thought?

The experience of an art show begins five to ten minutes before entering the gallery. That is what our artist Alvaro Barrington has told me. For a gallery, it is of great importance where you are located: who do you want to transmit to, who do you want to be in touch with. Our first gallery was just 50 metres down the road. The second place is still in Shoreditch. It was a conscious decision not to take up real estate, say, in Mayfair. There is a lot of empty, vacated real estate there at the moment. Hence a lot of young galleries have moved there. But we feel indebted to East London. We feel we have grown a community here. Just by the architectural feature of this gallery we are very transparent. You can look into our office from the street if you want to.

For a gallery, it is of great importance where you are located: who do you want to transmit to, who do you want to be in touch with.

Our openings and our average visitor is testament to the fact that we are in touch with young culture, we are in touch with young people – both from our generation and from the younger generation of current students. We very much value that.

To come back to the question of London. Angelina and I met at St Andrews. We quickly became best friends. A lot of people who studied in Scotland came down to London. That is the most obvious route and choice to do. In recent years, because of Brexit, our choice to be located in London has come under scrutiny. Our friends who no longer live in London say: Oh, London is over. Even people who live in London say that London is over. I am the biggest defender of London. London, for me, is truly the only cosmopolitan city of Europe. London will never cease to be relevant. The infrastructure and history of this place is just too big to be tied to some political decisions.

Our friends who no longer live in London say: Oh, London is over. Even people who live in London say that London is over. I am the biggest defender of London. London, for me, is truly the only cosmopolitan city of Europe.

In that sense, we are very well connected here. London is in the centre of the Eurocentric world. Every day there are five flights to whatever destination I want to fly to. Those flights tend to be cheap, too, because there is such a great offering of choices. We have six airports here. It’s unmatched. Which, in turn, means that many people come through London. If I were to open a gallery in Munich or Milan, you might get some important visitors once a year. People travel to London whether you want it or not.

There is no real economical advantage to paying a lot of money for everything you do. London is an incredibly expensive city. We’d pay half of the price in other cities of Europe. But the proximity to innovation and, as you beautifully said – a capital of thought, pays off. Every time I go to a dinner party here, you meet people who are pushing their field: finance, music, art. In order to survive, you have to be innovative. To make sense of living in this expensive city, you have to go out and meet with people. During the lockdown, we saw that London is not a particularly nice city. Without encounters, without people, there is no point in being here. For us it works just fine. I am a huge supporter and believer in London.

Malick Sidibé. Couples de danseurs, c. 1960-1970 / silver gelatin print

11.5 x 7.5 cm

29.5 x 25 x 3.5 cm (framed)

© Malick Sidibé

Courtesy of the artist and Emalin, London.

Photo: Stephen James

The mayor of London should use these endorsements for his campaign.

(Laughter.)

Before coming here, I asked some people if they have any questions they’d like to address to you. Inga Meldere, a Helsinki-based Latvian painter who is represented by Temnikova Kassela Gallery, would like to known how you keep your hand on the pulse of art in such a stylish and masterful way.

Oh, wow! That’s a wonderful compliment.

In 2017 – just one year after your opening, Artsy mentioned you as one of the top ten trendsetting young dealers. The image of being on the cutting edge of contemporary art is what still characterises your gallery.

I don’t want to be ageist, but one’s age does play a role. I am still relatively close to young people, not only artistic-wise but also in terms of consumer behavior. I really believe that the generation that evolved in the late 90s and early 2000s consumes innovation and general products in a completely different way.

Also, Angelina and I have different tastes in art and in things – it’s beneficial when we can work in symbiosis together.

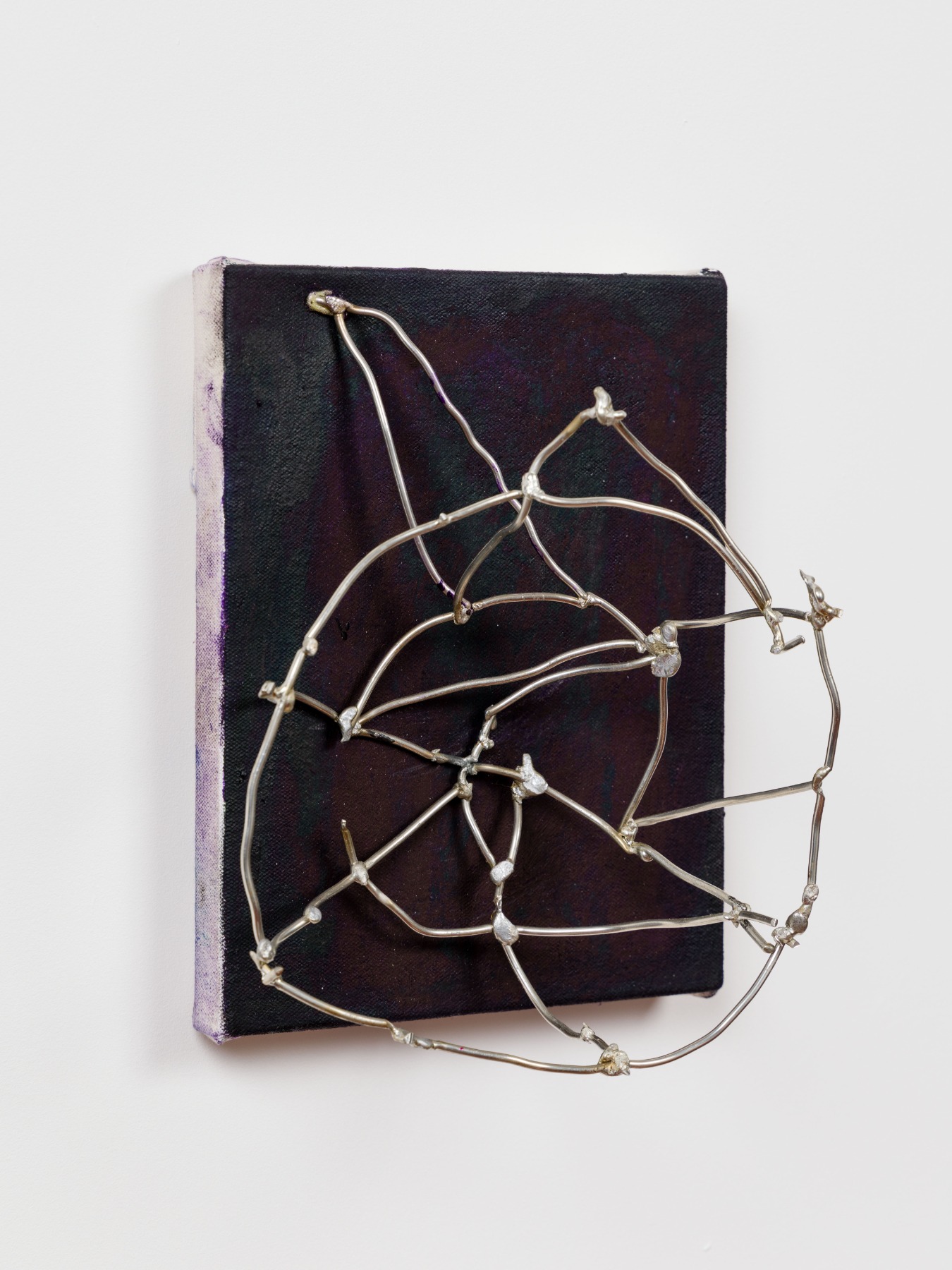

Jasper Marsalis. Event 7, 2021 / oil and solder on canvas

in three parts, each: 25.4 x 20.3 x 4 cm

© Jasper Marsalis

Courtesy of the artist, Kristina Kite Gallery, and Emalin, London.

Photo: Stephen James

Olga Temnikova would like to know what do you do differently than galleries from previous generations.

These points don’t apply exclusively to us but to the whole set of younger galleries. We have a very strong focus on collaboration. IGA (International Gallery Alliance) is a group of over 250 galleries from 53 different countries that came together just this year. This week we’re having a two-day Zoom summit. It’s the first time we’re all meeting. This is unprecedented – that so many galleries are collaborating, even if it’s just an exchange of ideas. Even the fact that they are all sitting at the same ‘table’ is a huge achievement. We are very happy to be part of it.

In the third month after opening our gallery, we were already hosting a gallery from Zurich in our rooms. I really think that this fluidity of what it means to collaborate helps a lot. Of course, our familiarity with technologies makes collaboration easier. Our generation has this innate understanding that we are all in the same boat.

I think the way we perceive culture also differs. We quote Colin de Land as an inspiration to us. He is the late husband of one of our artists, Kembra Pfahler. When he used to run his gallery American Fine Arts, Co., it was not a gallery for art – it was a gallery for culture. We, too, have had concerts here, performances, dinners, lunches. We have to release the grip on the idea that the art gallery should only show sculpture and painting. We should show what feels relevant. Our main aim should be building culture. We obviously need money to do this, and we are a commercial business, but ultimately we are here for culture creation.

We have to release the grip on the idea that the art gallery should only show sculpture and painting. We should show what feels relevant. Our main aim should be building culture.

In Marc Spiegler’s interview with Lisa Spellman from 303 Gallery, she stressed that when she started her gallery in the early 1980s, there was a lot of cheap real estate available all over New York and young galleries could afford to have a very experimental programme. Whereas galleries starting now are forced to be successful very early on because of the high prices of rent, etc. She thinks this stunts the creative strike of younger galleries today. Do you agree that there is this extra pressure? How do you find your way around it?

Maybe at the point when she was interviewed, it was not yet as clear that there will be a lot of cheap real estate available because of the changes caused by the pandemic. The picture is not as dark as people try to paint it. Obviously, it is more expensive to run a gallery now than it was in the 80s, but we also have more tools to be successful faster: technology and the ease of travel. It’s not too bad of a thing that one needs to be successful early on. We have to understand that we are running a business, we are in charge of people’s livelihoods, and we are in charge of artists’ careers. The least we can do is be professional. It doesn’t mean that our programming should be conservative. I think there are enough interesting collectors in the world that reward exciting programming.

So you are not pressured to make your artists stars sooner than they are perhaps ready, just for business purposes?

You can’t force stardom. I don’t believe that explosive career changes are beneficial to anyone.

Jasper Marsalis. L.F.W., 2021 / bowling ball, rock

in two parts:

bowling ball: 22.9 x 22.9 x 22.9 cm

rock: 27.9 x 20.3 x 22.9 cm

© Jasper Marsalis

Courtesy of the artist, Kristina Kite Gallery, and Emalin, London.

Photo: Stephen James

Before IGA, fairs like Art Basel and Frieze served as the sole meeting place for galleries. IGA heralds an alternative dimension of communication for galleries.

To be honest, when I am in Art Basel, I hardly speak to any other galleries because I am there to do my job. There is only so much time you have to socialise there because you’re tending to your clients and tending to artists. In that sense, IGA is for conversation. There I was, in a Zoom group meeting with two Indian galleries, a Swiss gallery, a Detroit gallery and a Mexican gallery. We had a wonderful conversation; it’s not as stressful as at a fair.

Many people from all walks of life have told me that thanks to Zoom, they’ve gotten to know their colleagues better. Before Covid, you barely met them in the cafeteria, whereas now you can have more intimate conversations.

It even works with WhatsApp. Olga Temnikova and I chat all the time. It’s nice.

What is the focus of your gallery?

We are interested in practices that have a political element to them (by politics, I don’t mean only party politics but also environmental politics, gender politics – politics at large) and that translate themselves into visually and materially appealing objects. The concept alone doesn’t stand; the form that is exercised when creating art alone doesn’t stand. Only a successful symbiosis between them makes sense for us. That’s when we get excited.

It is often pointed out that we have a focus on Eastern Europe, but that’s quite ridiculous because we have just as many American artists. People misread the subtleties of different cultures. The example we use is that we represent an artist who has been brought up in Siberia as an Orthodox Christian, and we have an artist from Chechnya who is Muslim. Their artworks couldn’t be more different. They live so far apart that New York and London are actually closer. The territory of the former Soviet Union has so many intricacies that cannot be subjected under a common slogan. We are not specifically interested in the former Soviet bloc; it’s just a coincidence that the art of these particular artists resonated with us. We are very open to represent more American artists, more Baltic artists, and more Russian artists if their work is interesting and appealing to us. But we never look first at someone’s nationality.

Jasper Marsalis. Event 12, 2021 / oil and solder on canvas, bowling ball

in two parts:

canvas: 25.4 x 20.3 x 16 cm

© Jasper Marsalis

Courtesy of the artist, Kristina Kite Gallery, and Emalin, London.

Photo: Stephen James

MoMA has been conducting a fellowship programme for curators from central and Eastern Europe over the last two years as an attempt to strengthen its programming from this region.

I do think however that the shadows of the Cold War are still present. We work very hard as a gallery and we represent great artists, and it’s not a coincidence that both Pompidou and Tate have acquired so many of our artists from this region. They wake up and say: Wow, not only have we ignored artists of colour, but we also ignored Eastern European artists. I really believe that the generation that was born just before the fall of the Soviet Union and soon after has incredible potential. They are some of the most interesting people out there.

One of the artists your antennae detected early on is Lithuanian artist Augustas Serapinas (b. 1990). How did you come to represent him?

I was invited to be a resident at the Rupert residency in Vilnius. Augustas was one of my first studio visits in Lithuania. We got on incredibly well. At that point he had never yet made a physical art object. What he had done while studying was open various secret places: places where you can think or talk. He was really very radical. It has been a beautiful journey ever since. We were the first ones who sold his first physical artwork. We opened our gallery with his solo show. His son was born just a week before his solo show with Emalin. He was the first museum acquisition we facilitated. He was our first artist to be represented at the Venice Biennale, the same year as Daiga Grantiņa was there. A lot of firsts with Augustas. We are the same age; we grew up together.

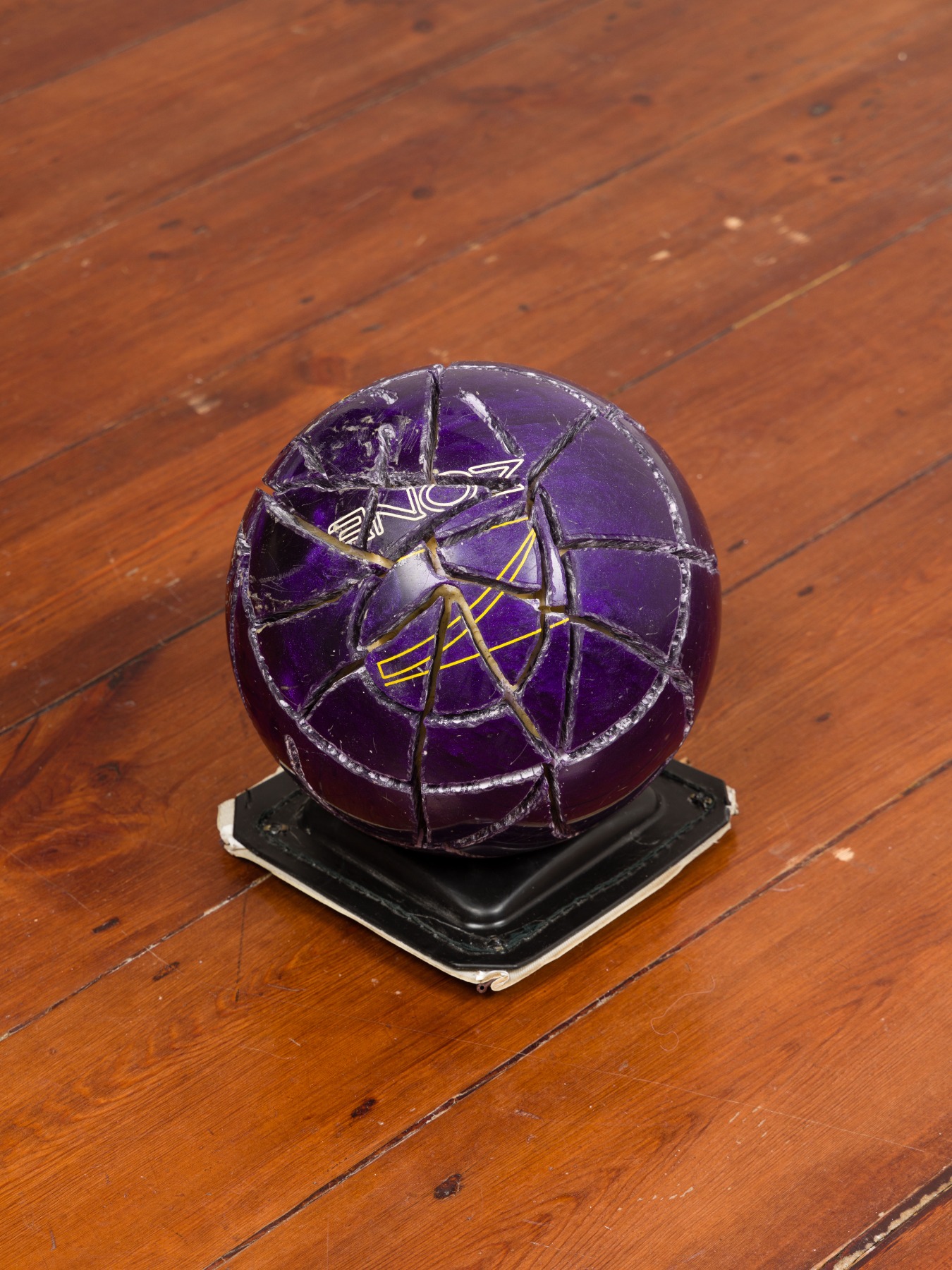

Jasper Marsalis. Event 12, 2021 / oil and solder on canvas, bowling ball

in two parts:

bowling ball: 33 x 21.6 x 27.9 cm

© Jasper Marsalis

Courtesy of the artist, Kristina Kite Gallery, and Emalin, London.

Photo: Stephen James

It requires a lot of openness to scout for artists in diverse places like Chechnya, Siberia and America. You have to go there, spend time there, do research. Not many art dealers are ready to go this far.

I think it’s curiosity. We were 26 when we opened the gallery. We were curious but also naive. For instance, we spent so much on our first show with Augustas that we couldn’t pay the next month’s rent. At the same time, his artwork was bought by a museum. So it paid off. There are certain risks you can only take with the naivete of youth.

How do you place an artist in an art market that is used to references from the Western art canon (even if said market denies this)? That was one of the stumbling blocks for some great Baltic artists from previous generations – their practice was difficult to translate into a Western art reference system.

Look, I have great faith in our collectors. It’s not the quantity but quality of the collector that matters. The gallery can get by with 50 very good, interested collectors. As a gallery, we try to engage collectors of our generation. Not to be ageist, but if I see the value in something, it’s more likely that someone from my generation will see it, too. You won’t hear 30-year-olds complaining: Oh, he doesn’t remind me of Rodin… They are aware of what’s going on today.

You sold the whole art show of the young Russian artist Evgeny Antufiev in Art Basel during the first day. Can you reveal to whom and how you did it?

We sold it to several collectors. We made a policy that one collector could buy only one work. It is important for us that the works are spread widely. Especially at this stage of his career. None went to a museum. We had already placed him in the collections of Tate and Pompidou. We went to Art Basel purely to meet interesting private collectors. There is no secret to our success. It’s a lot of hard work before that. That work started three years before we even started working with Evgeny.

A very good example of our work is that Evgeny was just in the New Museum Triennial. The only reason he was in the New Museum is that we had done a pop-up three years ago in an apartment and we had invited the curator of the New Museum to see the show. It’s a continuous process. It’s not as if you open a booth and hope that someone relevant will stumble in. The conversations mainly have been going on beforehand.

Dominique White. Flagged Out I, 2020 / sisal, kaolin, clay, raffia, wood, iron, sail, cowrie shells

196 x 80 x 20 cm

Why would a 30- or 40-year-old collector risk buying an artist that hadn’t been shown around much in Europe before?

I do hope that most of our collectors don’t see it primarily as a monetary investment. They believe in artistic qualities, in the stories that are attached to certain objects while also understanding that, thanks to our control, the artist is fully invested in his career. For instance, to avoid a situation in which you buy an artwork and three years later, the artist decides not to be artist anymore. I am not saying that every artist should always remain an artist. Cady Noland famously become an accountant, and she is one of the best artists still around. But then again, it was a conscious and artistic choice for her. It’s trust in us as a gallery that what they are buying will not just disappear tomorrow. At the same time, I cannot tell anyone that what they buy will grow in price in the future. It’s a conversation he/she might have with someone else, but that is not my concern. I cannot give that guarantee.

How do you build trust in such a short period of time? Your gallery is only five and a half years old.

Through the quality of the works. It is showing something that has been reviewed, that has been acknowledged as something pushing the boundaries of what art can be. We have never played it conservatively. We never have played safe. We always go all in. In our early shows we put all our money and time in because we believed in these artists. It’s a little bit like in a relationship. The only thing you can do when someone is with you is to trust. It’s a mutual trust. Taking many risks early on paid off. Because people said about us: Their head is on the line.

One more question from Olga Temnikova: Did you have many rollbacks when starting to work with Eastern European artists? Was it harder than you thought it would be?

No, absolutely not. There was a learning of cultural sensitivities. I think it’s very important, and we talked about it at length in our new gallery alliance – that instead of being Western gallerist who tell Eastern artist what to do, it’s more about understanding what do they want, what is their vision of their career. I don’t serve anyone if I only enforce my idea of what a career is. Everyone wants something different. We have had many open conversations with our friends in Eastern Europe about what is different there. It’s about being open to different approaches. Obviously, there have been some complications with shipping, but it’s nothing noteworthy, really.

I am keen to learn more about Eastern European collectors. We have some, but I want to experience more how they think and how do they approach artworks.

Your gallery is like this centre of cross-cultural studies. You study them with great eagerness.

If we would be trying to make money, we would probably have chosen a different job. All we have is exposure to other cultures. Not many realise that not only artists bring interesting viewpoints to the gallery but clients do as well. We work with some of the most amazing people out there. They are so generous. They come in, they tell us about their business, for instance, renewable energy. They are just as exciting as the artists. And how cool is that?

One characteristic that unites the diverse artists of your lineup is the performative element.

I see what you mean, but it all comes back to the question of culture. I really value artists who think broader than just one medium. It might also be just one medium, but their interests lie elsewhere, and they bring those interests forward.

How does Daiga Grantiņa’s work inscribe into the patina of your gallery? What attracted you to her work?

Very early on we organised a huge group show. We consigned a work by Daiga and we fell in love with it. It was so special – it was sculpturally too unique, precise. What I always tell people looking at Daiga’s work: nothing is left up to chance; everything is thought through in the most minute detail.

Soon after we organised a visit to her studio in Paris. It was lovely. Everything she said was to the point, every reference she pulled made perfect sense: she really operates her own congruous universe. At the same time, we were only 27. She said: I am very flattered by your interest, but maybe let’s talk again in a couple of years. Then we talked again two years later and it turned into this wonderful collaboration. Her first solo show with us in April 2021 was fantastic. We introduced a lot of new people to her work. We published her first artistic publication, with her husband making the graphic design.

Her sculptures are so performative. We are so lucky to have so many windows here. The show was literally like a movie. You could just sit there and watch the show all day: how different colours and different shapes were all there.

It’s very much in Daiga’s spirit. Her work always evolves… What’s next for you with her?

Her current show at the Art Museum Riga Bourse, which is in part the show that she exhibited at the Venice Biennale. Many works are reinterpreted. She had a group show at X Museum in Beijing recently. But I am especially excited about her Bourse Museum show, which is a very special homecoming for her: the reactivation of her Venice work.

What is your vision for the Emalin Gallery?

That’s a good question. We have a very long strategy meeting scheduled tomorrow. To be honest, we are exactly where we wanted to be when we started a gallery five years ago. With the help of a fantastic team and the artists that we represent, we have made it to where we are. It was being able to make a cultural impact in London, to inspire other people to also start galleries and project spaces, to have institutional backing. We do work very hard to place our artists in museums. Not to tick a box, but to give the work to people who will look after it – hopefully, for eternity. Also, our aim was to build a team. Now we have a team of five people, and it’s wonderful to keep the family growing.

Any ideas for the next five years?

A lot of plans, but nothing set in stone. We will see.

How do you work with museums? On your website you state that artists should not approach you with their portfolios. Do museums accept you approaching them with your suggestions?

It’s a dialogue. We are colleagues. The disclaimer on our gallery website is for the occasions when you receive an email which starts with ‘Dear galleries…’ and you understand that you have been Bcc’d with 200 other galleries. Every time we give a talk at art universities, we tell them: Choose which gallery you want to approach. Tell them specifically why your work is relevant for this gallery. We are super happy to engage in conversation.

Similarly, we don’t send emails to MoMA, Pompidou, Tate, etc. all listed as a Bcc saying, ‘Hey! Here’s an artist.’ We see what programme they are running, who is currently working at the museum, and we single out an artist that would make sense for them to look at. And we treat it as a conversation. You try to get them as excited as you are about what you are doing.

This may sound stereotypical, but it seems to me that you’re bringing ‘the German seriousness’ to the art market in London. I read in Francis Bacon’s biography that his first gallerist was German, the second was Swiss. They were the first ones who believed in his art.

I doubt it. And that circles back to the very beginning of our conversation: I am a Londoner. I have been living in London since 2013. The nationality in my passport doesn’t matter.

What advice or tips would you give to anyone interested in starting a gallery or a project room?

The main tip is: start with the necessity of having a group of friends that can be curators, that can be artists, that can be friends who are interested in collecting. Start with them. Don’t start a gallery with the solo show of a 50-year-old painter. The greatest dealers, if we think about Gavin Brown – he was an artist. The reason Sadie Coles’ gallery was born was that Sarah Lucas told her either you open a gallery or I’m going with another gallery. Being Jeff Koon’s studio manager at that time, Sadie Coles decided to quite that job and returned to London to open her own gallery. She was a part of the network of thinkers, creators, makers, etc., and that helped her in opening her own space.

That is how we built our gallery.

Start with the necessity of having a group of friends that can be curators, that can be artists, that can be friends who are interested in collecting.

Angelina Volk and Leopold Thun / Emalin gallery