Art: the most emotionally interesting and valuable part of life

A conversation with Māris and Irina Vītols

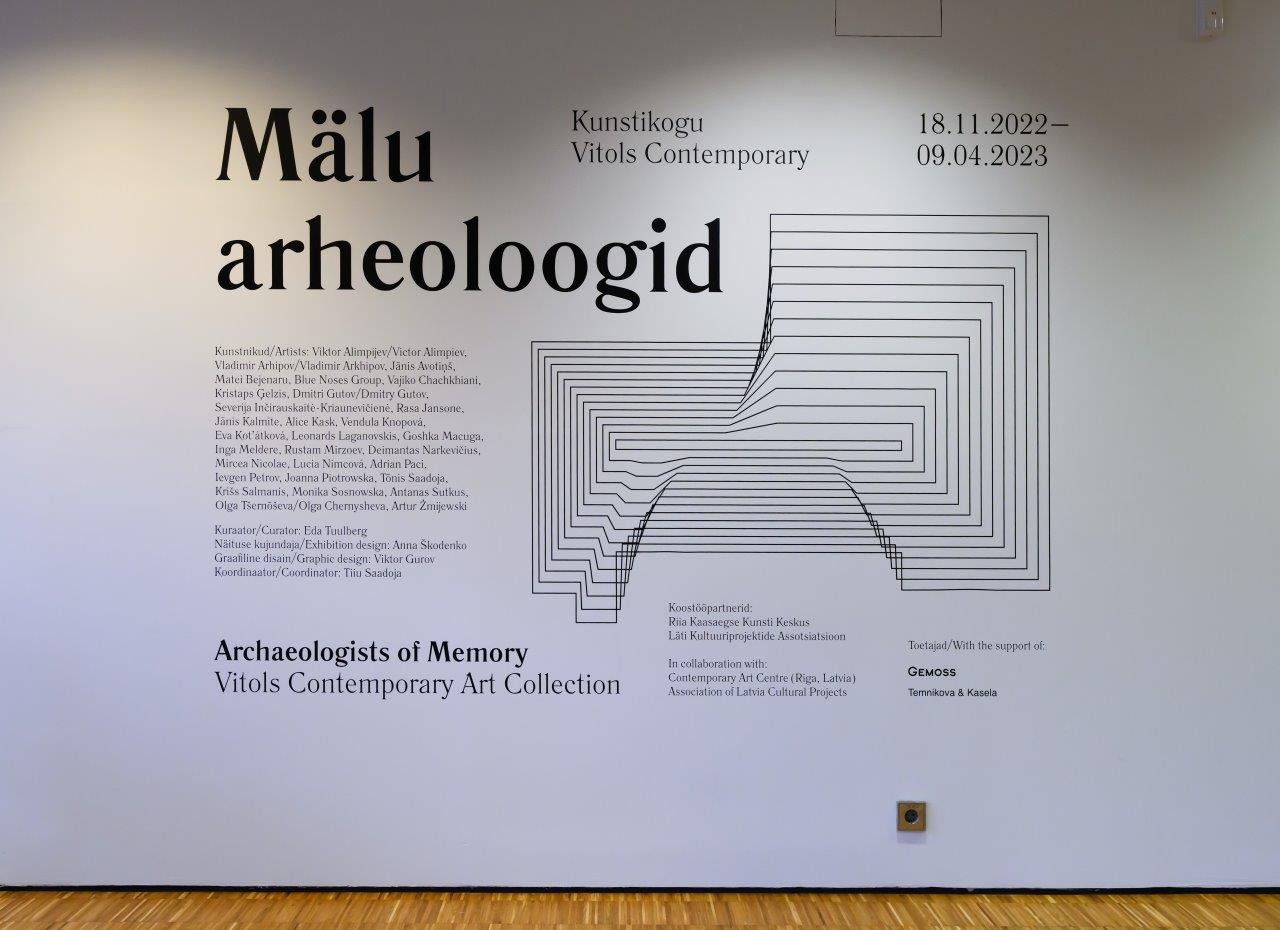

The exhibition Archaeologists of Memory is on view at the KUMU Art Museum in Tallinn until April 9; it is the first project to provide such a broad insight into Vitols Contemporary, the collection of Latvian art collectors Māris and Irina Vītols. Curated by Eda Tuulberg, the exhibition is located on the 5th floor of the museum and covers a total of over 1,000 square metres, offering viewers an insight into 150 works by thirty Central and Eastern European artists. Despite the scale of the exhibition, according to the collectors themselves, only about fifteen percent of their extensive collection of over 1,000 works of art is on display here.

Photo: Stanislav Stepaško

Vitols Contemporary focuses explicitly on Central and Eastern European art from the period after the fall of the Berlin Wall to the present day. Their aim is to follow along with all the political and social changes in the region. “We ourselves have been amazed by the cultural diversity we have discovered in our research on contemporary art from this region. [...] Visiting the exhibitions of many Western European institutions, one inevitably gets the feeling that artists in these societies lack challenges, both socio-political and everyday challenges. In general, the art scene there is like calm, slightly stagnant water. In our region, artists are characterised by a much greater energy invested in the creative process when making art. They have a spark. Here, the water is still rippling. Maybe it’s because of the challenges we still have in our everyday life or some other circumstances, but the hunger to make art is still much greater here.”

In addition to the wide range of artists represented, an important characteristic of this collection is the diversity of artistic mediums used – alongside the so-called traditional forms of expression, the Vitols Collection also contains large-scale installations, objects, and video art, which are not commonly found in private art collections in the Baltic region.

Archaeologists of Memory. Exhibition view at the KUMU Art Museum. Photo: Stanislav Stepaško

The exhibition Archaeologists of Memory, on view at the KUMU Art Museum in Tallinn until July 9, 2023, is the first such comprehensive representation of your art collection as a whole. At the same time, the show covers only a relatively small part of the collection. What is the conceptual underpinning of the exhibition, and why did you specifically select these works?

Māris Vītols: I’ll give a little insight into the archaeology of the exhibition. Irina and I had already collaborated with the KUMU Art Museum in the past by loaning out individual works from our collection for various KUMU exhibitions. About four years ago, we proposed to the museum’s management to collaborate and make a larger exhibition with works from our contemporary art collection. Initially, KUMU had the idea to create an exhibition project in a dialogue format, with a mix of works from both our and the museum’s collections. However, after KUMU did a more thorough examination of the Vitols Contemporary collection, they decided to make an exhibition with works just from our private collection; a show like this, sourced from just one private collection, was a first for KUMU. The museum, however, made it a condition that it wanted to realise the exhibition as a fully autonomous producer, which means that KUMU would be involved in both the production and financing of the exhibition. Irina and I were obliged to give the museum full freedom of action and interpretation with regard to our collection throughout the entire process of putting together the exhibition. The museum chose Eda Tuulberg to curate the exhibition; she was responsible for the layout of the exhibition and, of course, the concept and selection of works.

Monika Sosnowska (Poland), Untitled. 2017. Painted steel and concrete. Photo: Stanislav Stepaško

We were very attracted to this offer. It seemed great because it would be the first major thematic insight into our collection, and because the exhibition would be held in a large, prestigious museum in the Baltic region. I found the conceptual focus chosen by Eda Tuulberg – to look at our collection through the prism of the archaeology of memory – very interesting. It is important to have this view from the outside; it is intriguing how the curator sees this collection that has been more than fifteen years in the making. Tuulberg’s starting point was Walter Benjamin’s thesis in describing the functional mechanism of memory, where he says that memory is not an instrument for learning about past events, but more of a medium for accessing what is hidden; to access the past you have to become an archaeologist digging through all these layers of personal and collective memory. In Tuulberg’s conceptual set-up, both we as collectors and all the artists represented in this exhibition can be described as “archaeologists of memory” who draw inspiration from their personal memories, family archives, and individual stories as well as various events of the past. By uncovering the various layers of personal and collective memories, a past that is intertwined with the present is revealed. This thesis also guided the curator and her team in their selection of the artworks on view. The exhibition focuses on memory and the different ways it can function – from the artists’ diaries, their family archives, and the various stories that were important to them.

Also significant is the fact that the Estonian National Museum has published a comprehensive exhibition catalogue in English that includes, among other texts, an essay by Tanel Rander and a short story by Maarja Kangro, all of which complement the works on display. For us, this exhibition is a great impetus for further international cooperation – there are plans to send this catalogue to museum institutions in the region. Only 15 per cent of our collection – a very small part – is on display as part of Archaeologists of Memory. It is a view of the collection through one particular lens.

On the left - Antanas Sutkus (Lithuania). "Goodbye, Party Comrades!

Vilnius". 1991. On the right - Goshka Macuga (Poland/ the UK). "Death of Marxism, Women of All Lands Unite". 2013. Photo: Arterritory

But have you yourself, when you have bought works, ever looked at them from the conceptual point of view of memory archaeology that we’ve been talking about? What, in general, is your strategy for building a collection?

Irina Vītola: I think if we are talking about the archaeology of memory, then this concept is probably a new way of looking at it for us. We were both born in the Soviet Union; we lived through perestroika, the restoration of independence, and the crazy 90s. Our generation, the so-called Generation X, has its own characteristics and its own baggage. Of course, that plays into how we feel about these works and these particular artists who are often our peers. There are just a few who are younger than us. We definitely find something personal in there, and perhaps our choices are determined by our experience.

Why a collector buys particular works depends on many different factors. For me, it is the desire to own a work of art so that I can then share it. Sometimes you just can’t let something go – you have to have it. There are works of art that have long-term appeal, and there are works that once you’ve seen them, you feel that once is enough. Māris and I have had many discussions about why we should buy this or that work. Māris says that for him, it is all about the context and whether the artwork complements the collection, which was originally built on the principle that if we both liked it, we bought it.

I think that over time, it has grown into a museum-quality collection.

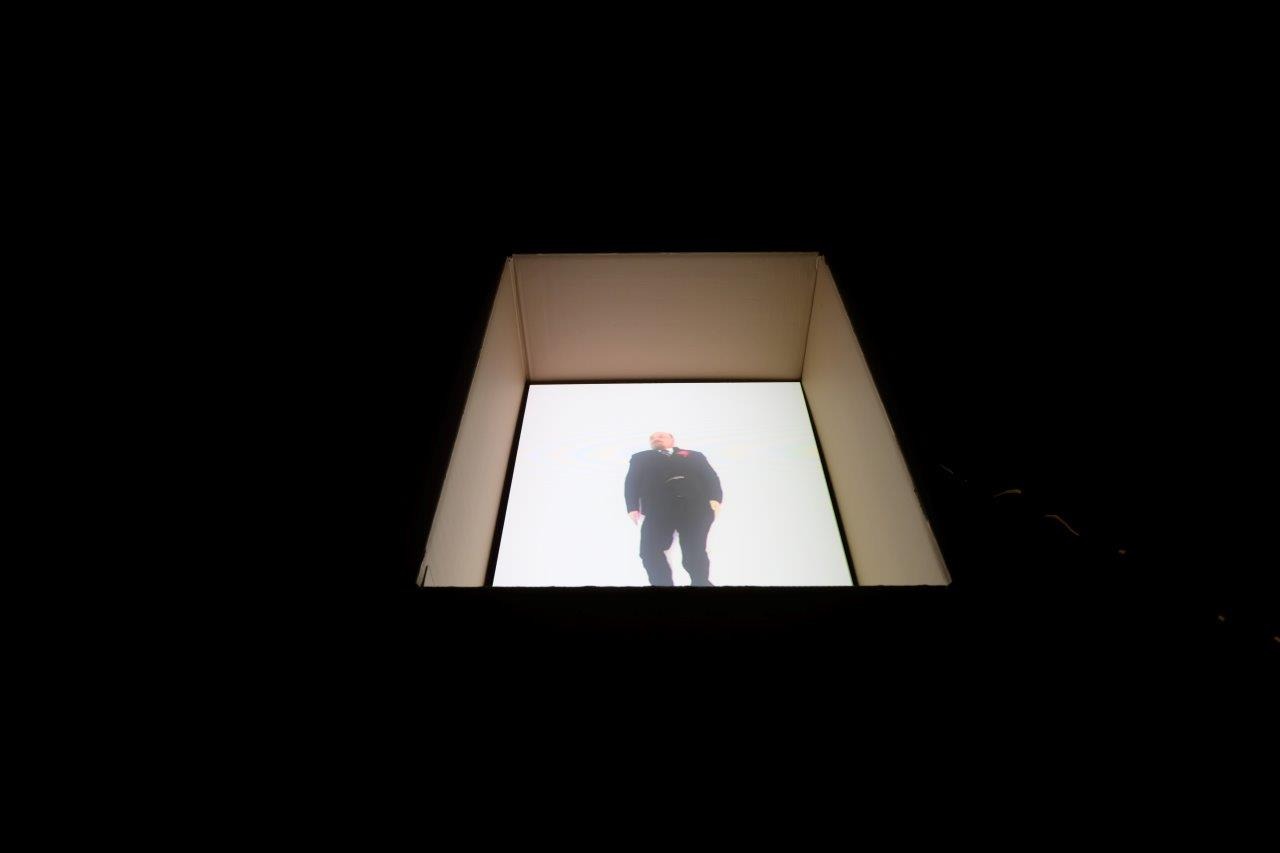

Blue Noses Group (Russia). "Lenin Turning in His Grave" from the series "Little People". 2005. Single-channel video, Photo: Stanislav Stepaško

M.V.: From the spontaneous start of our collecting, when the impulse to acquire artworks was quality art as a value in itself, we eventually came to the conclusion that when building a collection and choosing its focus, this should not be the only criterion for deciding on the acquisition of an artwork. The collection itself, as a body of artworks, must also have some further purpose for which it is being created and developed. When we chose the focus of our collection – contemporary art from Eastern and Central Europe made after 1989 (starting with the fall of the Berlin Wall to today) – we realised that we would try to follow all the political and social changes in the region. We have also been surprised by the cultural diversity we have discovered in our research on contemporary art in the region. And at some point, we came to the conclusion that the context was becoming more important than the art. It is also my conviction that in contemporary art, the context is often more important than the art itself; the possibility of adding different meanings to a work of art, the possibility of interpreting it, increases the value of the work of art. After so many years of collecting, the acquisition of new works of art is determined by the extent to which a particular work of art will make our collection more complete – what new dialogues it will stimulate. And we are still finding such works. We are currently in a very active phase of adding to our collection.

Vladimir Arkhipov (Russia). Apron Made out of Milk Packaging; unknown creator from the 1980s. Mixed media. Photo: Stanislav Stepaško

What defines Central/Eastern European art? How does it differ from the art of the so-called “Old Europe”?

M.V.: It differs in many ways. In the political dimension, some theorists believe that Eastern Europe and Central Europe, as concepts, have exhausted themselves – it’s been more than 30 years since the fall of the Wall, and the only context in which we refer to these concepts in contemporary art is the shared memories of the past and the trauma that goes with it. There is even a belief that the process of transition from socialism to capitalism, from totalitarianism to democracy, is complete. There is, for example, no difference between today’s Eastern Germany and Western Germany – the transformation phase is completely over. Therefore, in the context of art, there is also seemingly no basis for the widespread use of distinction between Eastern and Western European art, except within the limits of the memories and trauma mentioned above.

I totally disagree with this view. We can look at Poland, Hungary, Slovenia and a number of other countries and see that the values of democracy are absolutely undefended, they are not alive, and they are not irreversibly entrenched in the public consciousness. They still need to be fought for and defended. In many Central European countries, there are attacks not only on the free press, but also on the autonomy of educational and cultural institutions. In Poland, for example, in many places professionals in the management of state-run museums are being replaced by puppets who are obedient to the ruling politicians and then censor the museums’ exhibition programmes; meanwhile, artists actively participate in political demonstrations. In terms of democratic values, we are nowhere near where Western Europe has been for decades in terms of the process of change. Accordingly, not all goals have yet been achieved. Far from it. And all of this makes the concept of Eastern Europe relevant not only in geopolitical terms, but also in the context of contemporary art.

Vladimir Arkhipov (Russia). "Genady Vladimirovich’s Bathtub-Bed". 2001. "Janitor’s Shovel Made out of a Road Sign". Photo: Stanislav Stepaško

Another important nuance is that the war started by Russia in Ukraine has once again put our region in the spotlight of the whole world. The first time was in the aftermath of the fall of the Berlin Wall

in 1989. Today, American troops on NATO missions to Latvia and Estonia are heading to Eastern Europe. The war in Ukraine has brought this region into sharp focus.

I.V.: If we look from a historical point of view, different peripheries and other life experiences, as well as different social conditions, have made us different from Western Europe, which lived a subdued and peaceful life after WWII. And, of course, all the events of the late 80s and early 90s have left their mark. And the artist reflects what they have personally experienced and what is happening around them. These are the different external and internal conditions that distinguish Eastern European art from Western European art.

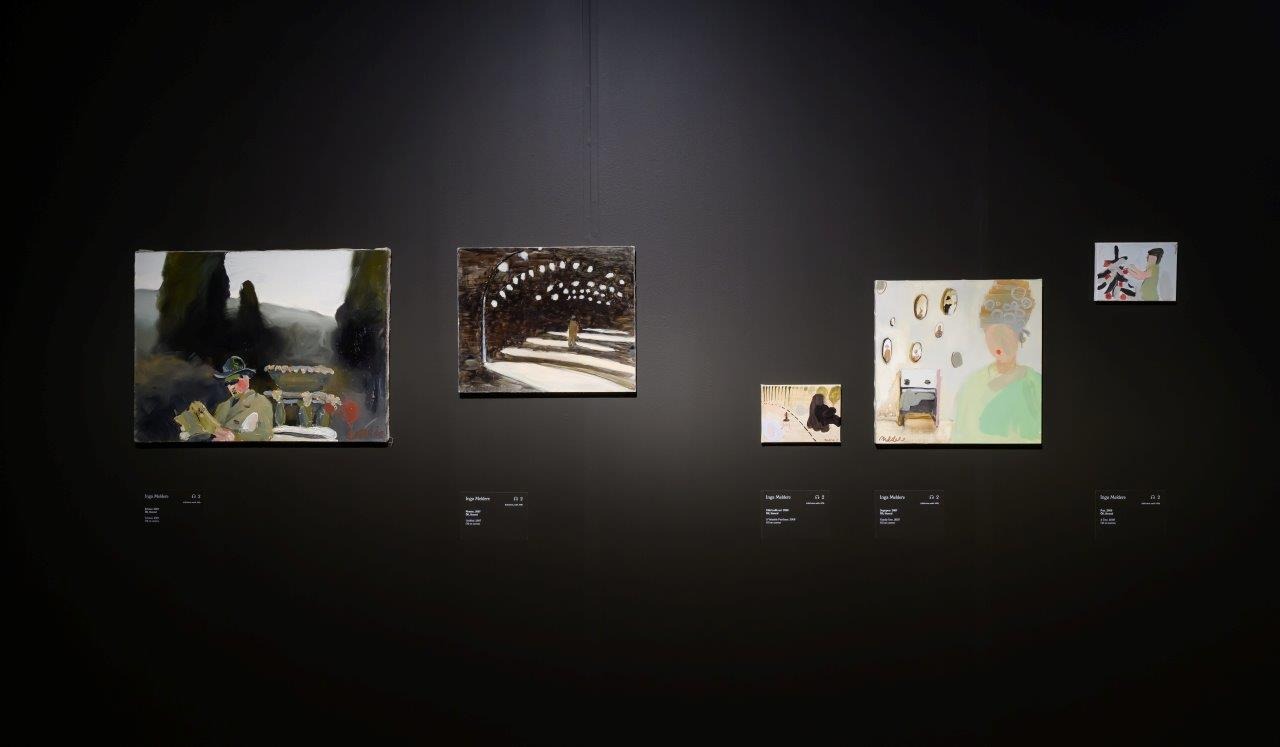

Inga Meldere’s (Latvia) paintings. Photo: Stanislav Stepaško

M.V.: Visiting the exhibitions of many Western European institutions, one inevitably gets the feeling that artists in these societies lack challenges, both socio-political and everyday challenges. In general, the art scene there is like calm, slightly stagnant water. In our region, artists are characterised by a much greater energy invested in the creative process when making art. They have a spark. Here, the water is still rippling. Maybe it’s because of the challenges we still have in our everyday life or some other circumstances, but the hunger to make art is still much greater here. And also the fact that, taking into account how underdeveloped the art markets of Eastern and Central Europe are, the art created here is not primarily created with the aim of selling it. Its occurrence is influenced by other impulses.

I.V.: Because you can’t not create.

M.V.: If we talk about the process of creating art, there is a completely different energy here. This is what makes us happy and we discover it regularly when meeting with artists and visiting exhibitions of this region. Of course, there are exceptions in Western Europe as well. I don’t like to make generalizations, but when I talk to the curators of museums in the Western world, who now have the opportunity to get to know more and more about the art history of Eastern and Central Europe, it turns out that they find this (so far) little-studied territory very vital and intriguing.

Rasa Jansone (Latvia). Lost Treasures. 2008.

Installation. Photo: Stanislav Stepaško

But to what extent are Western art institutions really interested in the art of our region?

M.V.: It could be said that Western art institutions have so far shown little interest in us – that they have their own goals, that they are indifferent to what is happening here. But this is not true. For more than ten years now, Western art institutions and museums have been inventorying their art collections within the framework of postcolonial discourse and other current ideologies. This is done not only with the aim of including the works of female artists who have been disproportionately under-represented until now, but also in a bid to acquire works created outside the geographical boundaries of Western Europe and North America. The flagship of this movement is certainly MoMA in New York, which in 2009 had already created the CMAP (Contemporary Modern Art Perspectives) interdisciplinary research programme, which studies the history of art in three regions outside its usual sphere: Africa, Asia, and Central and Eastern Europe. In 2019 MoMA released an excellent collection entirely devoted to Central and Eastern European art. It’s a wonderful book, but there is one drawback – it covers all of the countries of the region except for Latvia and Estonia. The Lithuanian art scene is analysed and studied very extensively, but they haven’t gotten any further. We’re expecting the MoMA team to come to Latvia next spring, including to the exhibition at the KUMU Museum.

Tõnis Saadoja (Estonia). The Melting of an Ice Cube.

2003. 20 oil paintings on HDF.

Photo: Arterritory

Moreover, the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam has also started building its collection of Central and Eastern European art. In all of its new programmatic exhibitions, Tate Modern is revising its methods and modes of organisation with the aim of including a wider range of geographic locations. I think this could have an avalanche effect on the contemporary art of our region – I’m assuming that in the next decade, a series of exhibitions of art from this region will be held in the large museums of Western Europe. Consequently, our collection also fits into this current context, and the exhibition of our collection at KUMU, in my opinion, is a good instrument with which to introduce curators of the big museums to one of the aspects of the contemporary art scene of our region. We hope that by April 9 of next year it will be viewed by several representatives of Western European institutions with whom we were in very close contact during the preparation of this exhibition.

Archaeologists of Memory. Exhibition view at the KUMU Art Museum. Photo: Stanislav Stepaško

You already mentioned that the war in Ukraine has drawn attention to our region again. However, in my opinion, there is another nuance here – in a strange way, through this madness, the art of Eastern and Central Europe has probably also regained its sense of self-confidence.

I.V.: I think it’s a question of identity – how and with whom do you identify. Starting with our art academy, where skills and proof of having some talent are still important. Whereas in Western Europe, signs of talent and the ability to craft something is often not necessary.

We are interesting in our own right. This year we visited both the Venice Biennale and documenta in Kassel. In my opinion, both are united by the fact that it is more a story about the process than the final result. To be honest, it is less clear to me where the Western European view of art is going than ours. At some point, identity becomes important to everyone – including Western Europe and North America.

Severija

Inčirauskaitė-Kriaunevičienė

(Lithuania). Kill for Peace. 2016. Installation. Photo: Stanislav Stepaško

What is the ultimate goal for both of you – what do you see as your collecting mission, and what would help the art of this region survive and exist?

M.V.: If we’re talking about public art museums and their collections, in small economies such as the Baltic States it is important for museums to take care of the local heritage and cultural landscape within the scope of existing state funding; they have very little opportunity to include examples of foreign contemporary art in their collections and make cross-national comparisons. As a private collection, we have this advantage of creating a more multi-voiced dialogue between the artists of this region; this is one of the goals of creating our collection.

But the second main goal is to cooperate with Western museums on an equal basis and try to create projects that exhibit artists from our region in the context of Western Europe. As I have already mentioned, the current prevalence of Eastern Europe in the zeitgeist will open such opportunities for cooperation in the coming years. I’m not talking only about Ukrainian art, but about the whole region as one unit.

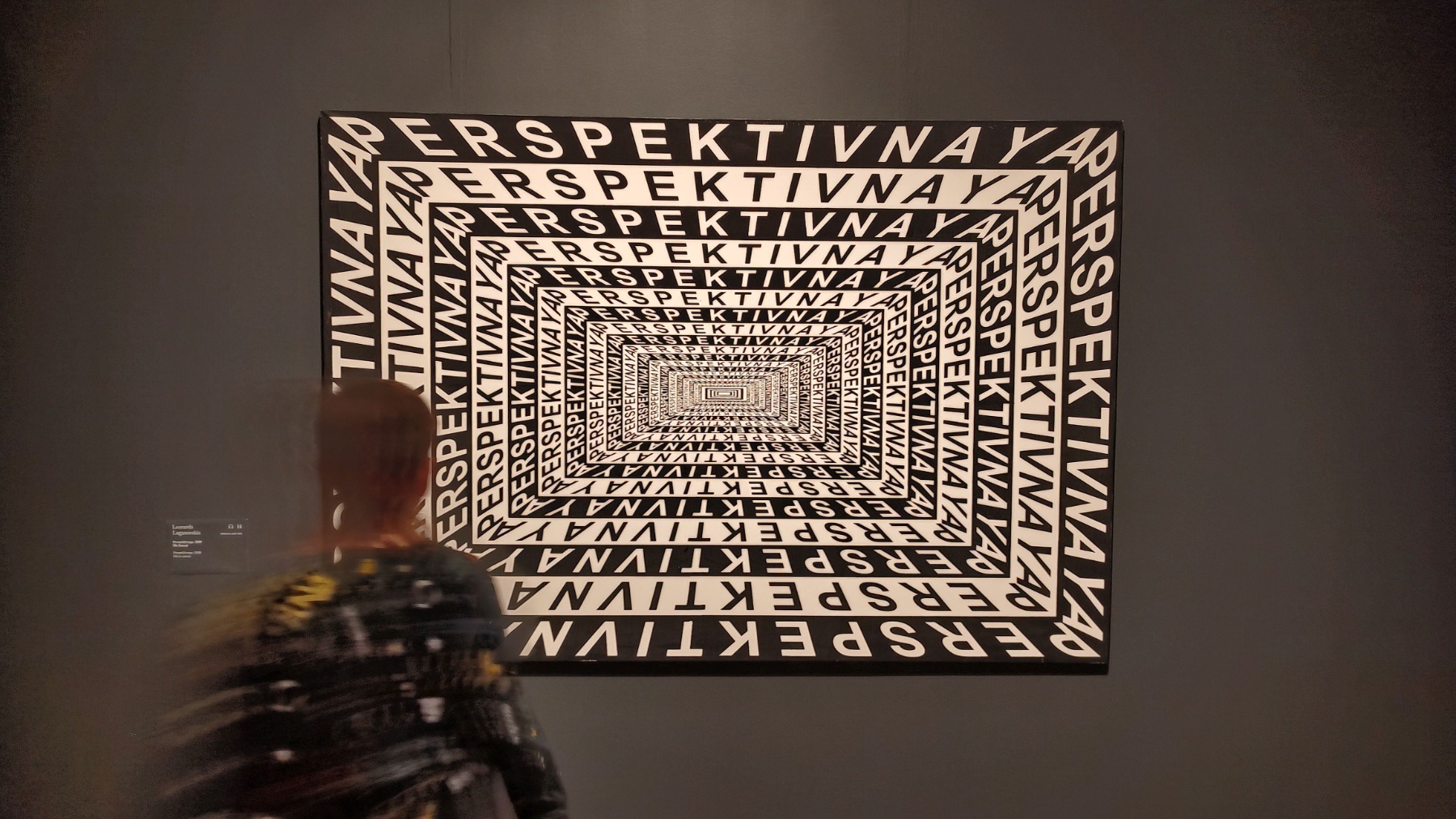

Leonards Laganovskis (Latvia). "Perspektivnaya". 2009. Photo: Arterritory

There are not many serious collectors in Eastern and Central Europe. And those who are, do not always know each other or collaborate. In fact, an event like the exhibition of Baltic collectors at the Zuzeum Art Centre is an excellent example of how to create and develop such joint projects in the future. There were several collectors to whom we were introduced during this exhibition. However, we already have had several collaborations with other world collections with a similar focus – Central and Eastern European art after the collapse of socialism. We are currently cooperating with two such collections (both are corporate collections) – the Deutsche Telekom collection called Art Collection Telekom, which is being created by the Berlin-based curatorial group Office for Art (Rainald Schumacher and Nathalie Hoyos). About ten years ago, they also decided that the focus of the Telekom collection will be exactly the same region as that of our collection.

A similar situation exists with another large collection based in Vienna – the Kontakt Collection. It is being created by Erste Group, which ten years ago was collecting Austrian conceptual art created between the 1960s and 1970s; but then, taking into account Austria’s geopolitical location and history, they decided to fully focus on contemporary art from Eastern and Central Europe. Polish art critic and curator Adam Szymczyk also works on its board of curators.

We have a good relationship with the creators of both of these collections, and perhaps we will also create joint exhibition projects in the future.

There are various collaborative ways in which we can expand the audience for Central and Eastern European art and expand the context in which it is shown to the world. Everything is determined by common interests, and in my opinion, there is a desire to delve into the art of this region and it is increasing with every year.

I.V.: Actually, a lot is determined by communication, personal contacts.

Jānis Avotiņš (Latvia) paintings. Photo: Stanislav Stepaško

Networking.

I.V.: Yes, exactly – yet another thing that makes our life interesting. It is also almost like one’s civic duty – to show that there are also good artists in Eastern Europe and Latvia. I want to open that door wider.

M.V.: For example, for a long time Deutsche Telekom bought works of art only from those countries where the company had ongoing business projects, so the Baltic countries were automatically excluded. But now their collection also includes the works of Paulis Liepa – he is the first artist from the Baltics whose work has been acquired by the Telekom collection. Both curators attended the opening of our exhibition at KUMU, and I learned that over the next couple of years, they want to focus mainly on the Baltic States. Irina and I will try to help them as much as possible and will inform them about all of the most important contemporary art events going on here. In this way, this cooperation of ours strengthens the contemporary art scene of the Baltic States by involving new participants into it.

On the left - Blue Noses Group (Russia). "Kitchen Suprematism". 2005. On the right - Leonards Laganovskis (Latvia). "McLenin I". 2008. Photo: Stanislav Stepaško

During a crisis, the role of art becomes especially important – both in an emotional context and also as a way that can address and inspire people as well as provoke discussion and encourage thinking. What do you think is the power of art?

I.V.: Art encourages a person to create and develop a creative approach, which is so necessary in various life situations. We started collecting in order to fill the empty walls of our house. And then you begin to understand how wonderful a room becomes when there are places to focus upon. Orthodox and Catholic churches are overflowing with holy images. When a piece of our personal “home art” is sent off to an exhibition, there’s a feeling of emptiness.

I think that art helps to overcome life’s trials; observing a work of art provides an opportunity to find solutions to one’s problems, to one’s own life. I believe that art promotes creativity in many ways and that it also has an economic impact by stimulating human creativity. Of course, there is also music, film and theatre, but I think that visual art can provide a much more personal experience. My first workplace was the Stockholm School of Economics in Riga in 1994, where Professor and Rector Hans Martin Staffan Burenstam Linder believed from the beginning that a space should be filled with works of art; that for students majoring in economics, the presence of art is very important – that there is a “reciprocity” between economic growth and art. At that time, Helena Demakova created the so-called "Swedish" collection there. And I think that some of the students from there have also become collectors, attend exhibitions, and are interested in art.

Artur Żmijewski

(Poland). Singing Lesson 1. 2001. Single-channel video. Photo: Stanislav Stepaško

M.V.: Contemporary art is also an excellent platform for positioning and discussing various ideas in modern society. Including very topical issues. It is a completely different way of looking for and offering solutions to problems that are important to society. It can develop a more inclusive society, deeper empathy for marginalized sections of society, and is a way to talk about values that are important to everyone. Discussions that take place in the context of contemporary art can also reach societal groups who are not looking for answers in the discussions of politicians.

I.V.: The influence of art is indirect and makes life interesting. It’s an interesting, colourful, exuberant life.

M.V.: For us personally, art is probably the most interesting and also emotionally valuable part of life. We are extremely grateful that we have the opportunity to collect art and share with others the ideas of art – the values that are important to us and that we want to tell others about.

I.V.: And now the collection is already living its own life.

Lucia Nimcová

(Slovakia). "Exercise". 2007. HD video. Photo: Maris Raud

Title image: Māris and Irina Vītols. Photo: Maris Raud