Tripping on ice cream

An interview with Greek artist Jannis Varelas

Greek artist Jannis Varelas is at once an observer and a sharp-eyed archaeologist of the everyday. His work focuses on the human condition, which he reveals by reconstructing seemingly mundane everyday situations. He creates reality by zooming in on commonplace episodes, confronting us with what is present but not always noticed, as well as changing the perspective of the small details that make up the totality of being.

Varela’s works seem to connect the conscious and the unconscious, the past and the present. In a multi-layered way, full of healthy irony, seemingly a little childish but at the same time jaggedly direct, they open up new dimensions of possible narratives – both deeply personal and in the context of current socio-economic and historical events.

In a sense, Varela’s works are visual chains of thought, initially solved and indulged in by the artist himself, but later taken over and engaged in by the viewer. The work of art becomes an instrument of transcendence, or as Carl Jung once described the essence of creativity: “a living thing implanted in the human psyche.”

Born in Athens, educated at the Royal College of Art in London and The Athens School of Fine Arts, Varelas also spends much of his time in Vienna and Los Angeles. He uses various mediums in his work, ranging from painting, collage and sculpture to video art and performance. Varela’s work can be found in many prestigious private collections and has been exhibited at such esteemed art institutions as the Belvedere Museum and Kunsthalle Wien in Vienna, the Palais Tokyo in Paris, the Saatchi Gallery in London, the New Museum in New York, and the Kiasma Museum of Contemporary Art in Helsinki, among others.

This autumn, Varela’s solo exhibition The Salted Milk, the Fire is Blue, a story about the absolutely ordinary cognitive activities of life and their impact on the subconscious, was on show at the Krinzinger Galerie in Vienna. Seeing, hearing, eating, leaking, standing and moving are activities that we repeat every day, and starting from a very young age. We’ve been doing these things for years, and we will continue to do so – the question is whether and how we notice them, experience them, and what they can tell us about ourselves and the world around us. For example, a very ordinary and familiar self-indulgent pleasure from childhood, such as eating ice cream or licking it.

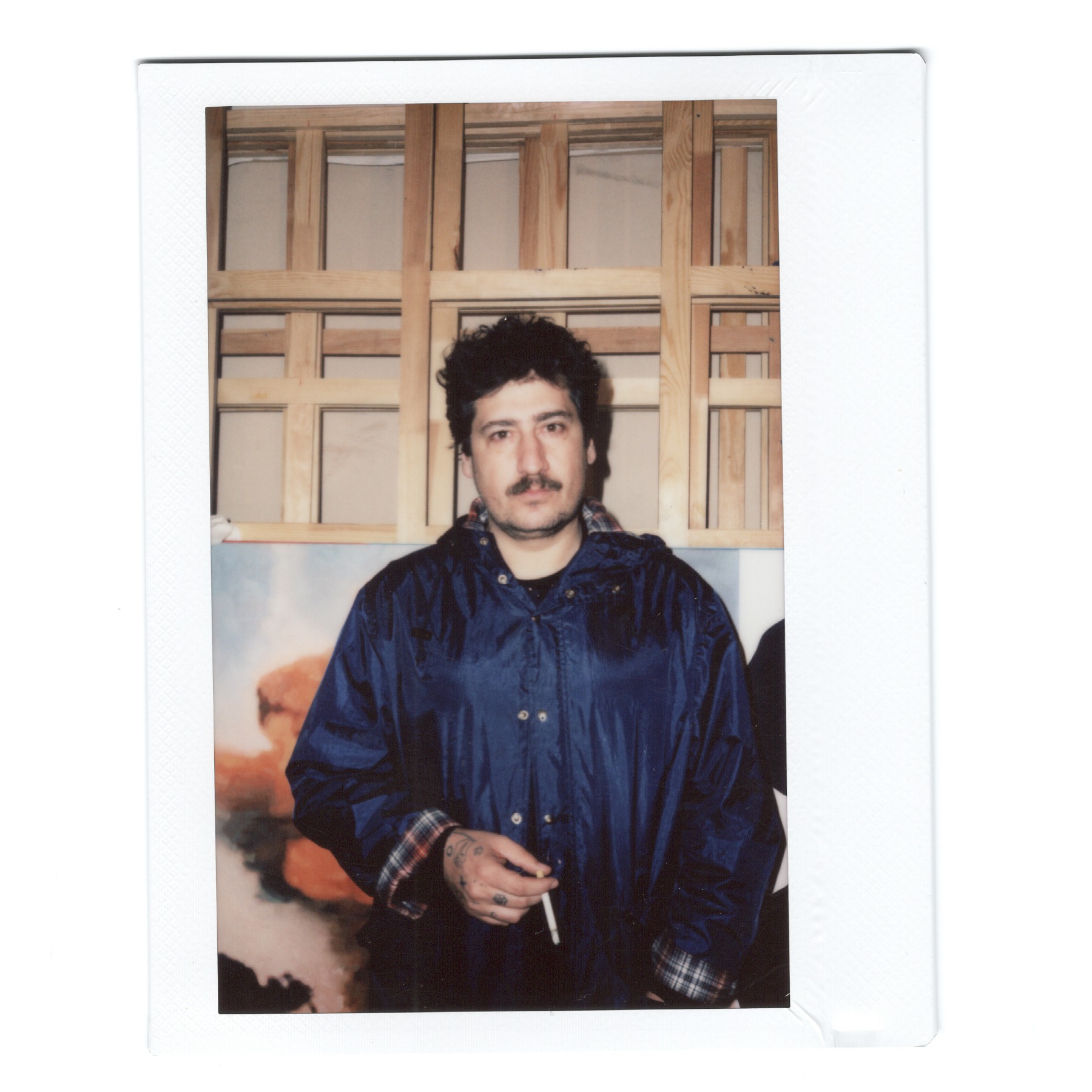

Jannis Varelas. Photo: Tasos Gkaintatzis

I would like to start our conversation with the work I recently saw at your solo show at the Krinzinger Gallery in Vienna. Titled The ice-cream tower, it is a huge mixed-media installation showing elderly people eating ice cream. There is something hypnotic and disarmingly human about it; the work makes you smile, and it’s also very revealing. It speaks about something as seemingly ordinary as eating an ice cream, but at the same time, it tells a story about ourselves. At the moment of eating an ice cream, people are not controlling the process in which they’re doing it, they’re not controlling their emotions – they are just eating an ice cream. Basically, they are who they are.

I wanted to create a situation in which I could see a person experiencing a transcendent moment – not acting but losing control and going somewhere else. For a couple of minutes, maybe. I came up with the idea of eating, but then what is something that eating it could give you this kind of a transcending experience. Of course, ice cream is one such thing – you eat it and then you simply start tripping with it. The classic association is children eating ice cream, but I wanted to expand beyond that. I invited nine elderly people to come to my studio and to do this act. We had a fridge full of ice cream, and we filmed for around eight hours. It was also important to have an ice cream without sugar, because otherwise it could be dangerous for them. So it was quite expensive.

The direction was like, okay, just start eating the ice cream; you don’t have to do anything else, just eat it, and we’re going to film you in close up. At the very beginning it was awkward – they didn’t know what to do exactly, so they were eating the ice cream in a very weird, funny way. But after maybe ten minutes, they got used to the environment. They didn’t care about the camera anymore, and at one moment they just started tripping. What was fascinating during that was that you could see that each one had their own experience, as if they were going to someplace else, each one in their own zone. And after a while, like, after 31 minutes of filming, you would see that they didn’t care anymore. For an hour or two they were just eating ice cream, and that’s it. And it was great, because at the end I kept like two or three minutes from each of them – the moments of complete transcendence.

Afterwards, when I asked them how they felt during the whole process, they said that in the beginning it was awkward because there was a camera in front of them. But then – as they really liked the ice cream – they started recalling memories. They were revisiting their life, in a way, and then they just became absent-minded. They didn’t have anything else there – they were just looking at things, you know, the room, the lights – just enjoying the situation in their mouth, the taste, and it was really interesting.

The piece talks about the ability of a human being to transcend and go somewhere else using something as common and straightforward as eating ice cream. And about exploring how far you can go towards your own zone.

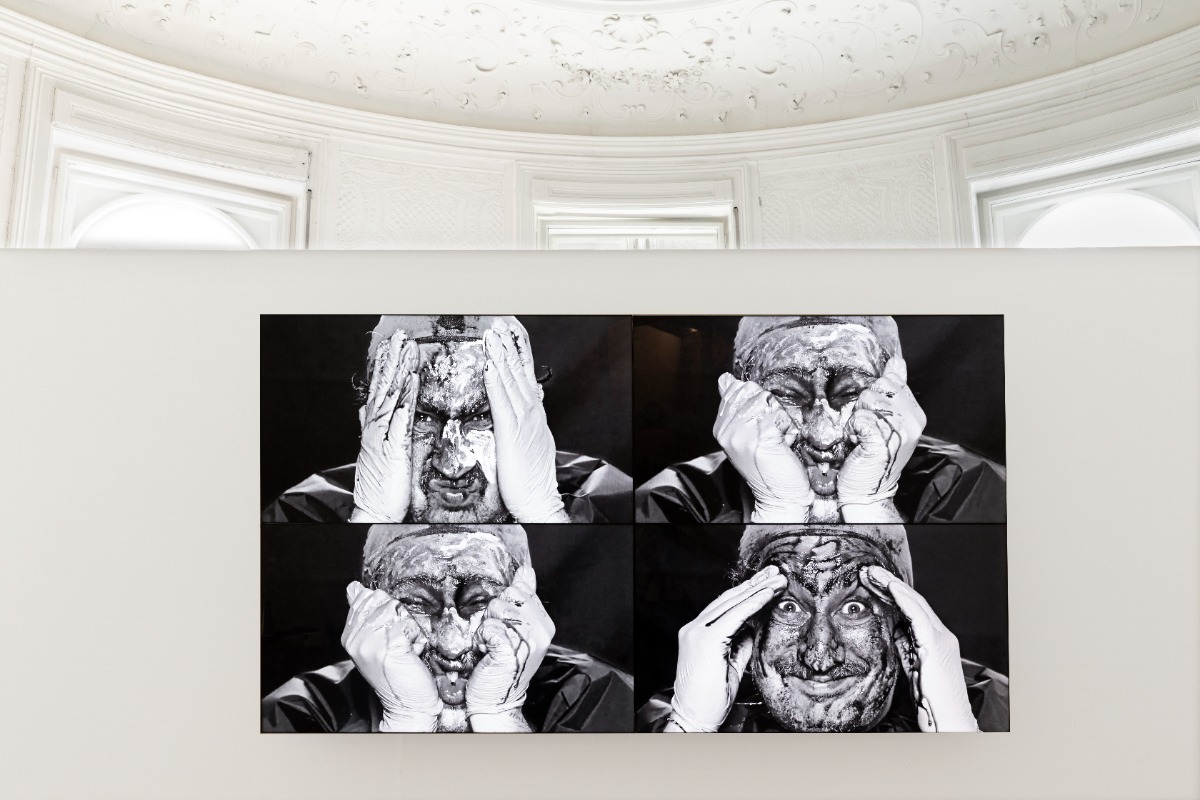

Jannis Varelas. Exhibition "Salted Milk, the Fire is Blue" / The ice-cream tower. 2022. Video installation. Courtesy of Galery Krinzinger

As in, we do not need psychedelics or other substances – sometimes an ice cream is enough...

It’s a question of context, I think. I mean, if you just let it go and enjoy the moment in whatever you do, I think we have the ability to just go somewhere else. Transcend and enjoy because, at the end of the day, the most interesting thing of this process, for me, was that they didn’t realise how much time had passed. In the beginning, you’re worried that after about 20 minutes they will start complaining – Oh, I don’t like this...I need a break... – whatever. Time went on and they didn’t even notice that an hour had gone by. Another very interesting thing was how deep this kind of trip can go.

I think it’s quite interesting that one cannot control how one eats an ice cream. It says a lot about you as a personality. You could dress up, you could pretend you’re this or that, but at the moment you start eating the ice cream, all masks and mind constructs are gone.

Yes, it’s a kind of nudity; whatever your intentions may be, they all drop away. It is just you and the thing. I was very happy because at the end of the day, when you see the piece, you’re able to see that [the people who were being filmed] are somewhere else – they don’t care about anything except what they’re doing at that moment. It’s quite interesting.

I recently had a strange dream – essentially, we all are artworks of nature/the Universe, but we don’t recognise it because we’re always busy running somewhere and doing something. But when we take a moment to look at art, we see that, in some way, it is like a mirror showing us that we are also a work of art. To be more precise, it reminds us of this fact. Would you agree, or do have your own take on this? It was a really interesting and powerful dream, and I still feel it resonating within me.

That’s a very interesting observation. I mean, there is a comprehension of humanity, as a whole, being the way for nature to understand itself. As in – creating humans (or other species) with the ability to think and rationalise, to feel and understand, and to dream and imagine could be a way of nature understanding itself. So, if we agree that we function as a whole – that humanity functions as a certain type of nature’s subconscious structure – then with art, you can reveal this kind of truth. If you can achieve showing this ability of humanity, or this kind of major role or starting point of humanity, then I think you’re achieving a cognitive level of understanding of what you/we are all about. I think it’s a very profound moment when this happens, as then you start thinking about a certain type of causality in life, or a certain way in which to understand yourself within the context of society, the context of culture, the context of nature itself. So, yeah, in a way I agree with your observation. We are part of it, certainly, and we are part of it in a very complex but, at the same time, straightforward way.

Jannis Varelas. Salted Milk, the Fire is Blue. Installation view. Photo - Courtesy of Galery Krinzinger

Do you ever think about or notice where you are – as in which state or realm – when you are creating art/working on an art piece? Of course, physically you are in your studio, but I have a feeling that there is more to in than just that.

At the moment of creating, what I’m trying to do (or what I’m trying to go into), is to present a very structural but also very free understanding of oneself. I subscribe to the idea that human beings can become whatever as long as they get attached to what is around them and what it is that they want. What is the real wish that they have? And that goes along with identity issues, understanding one’s surroundings, or also towards one’s own understanding of oneself, like who you are. I think that’s why I choose to work in a very precise way, especially within painting. I’m trying to create as well as I can the structural parts of an image – the clothes, the background, the surrounding space – like paraphernalia, the little objects and things like that. But when it comes to the human being itself – like the head or the face or the hands – that becomes way more abstract and way more fluid. So, I try to show this kind of coexistence of two very opposite situations: a very fluid structure as a human being, as a body, but you also have a very structured situation around you – the clothes, the space, the surrounding objects. An understanding of the two kinds of worlds that coexist is a quite interesting point of view. You know, in the realm of physics, it would be like something being a particle and a wave at the same time – it’s kind of the same idea. That duality of existence in terms of understanding something, understanding yourself, understanding people around you, understanding your surroundings, and understanding society, in a way. So this is where I am at the moment – this kind of situation in which things can be two different kinds of things a the same moment, like two sides of a coin.

It’s interesting how you pick up everyday moments and then blow them up and zoom into them, thereby giving us completely different viewpoints.

Exactly. You know, a lot of people, when they see my work, they read a certain realistic kind of approach, but I keep telling them that to me, it’s not like that. That’s why I try to use very simple situations, like somebody is standing in a room, or sitting in a chair, and it isn’t about the magic that is created within a very weird or “off” situation. To me, it’s very important to focus and zoom into very simple everyday situations, and in that way expose their transformative or magic qualities. That’s why, for example, when I paint an orange, or a piece of cloth, I try to be very, very precise, to zoom into the details, because I think that creates the impression of vastness. You know, space could be endless. I try to overlap the concept of time, the concept of motion.

Sometimes I depict static situations, like someone standing or sitting, or just looking at something. Because I believe that there are other things that are more interesting than action, you know. My starting point is doing nothing. For me, it’s way more interesting to depict a human being standing than to depict a human being running, for example.

Jannis Varelas. Salted Milk, the Fire is Blue. Installation view. Photo - Courtesy of Galery Krinzinger

It’s been confirmed by neuroscientists that we are what we see and what we have seen in our lives, and that zooming into small details could, in some way, also expand our way of seeing – as in seeing the details and then making the whole picture from them but in a totally different way.

In a way, yes. You know, the funny thing about that is that when you understand the way of zooming into things, you understand their position; you understand time, distance. For me, it’s very interesting, for example, to be able to suggest that there’s a vast amount of space between an orange and a leg. And this tremendous amount of space, just within this little gap, can create a whole narrative structure. You can actually feel everything there, or as much as you want as a narrator. So, this is where I am at the moment. Trying to observe and imagine these kind of situations, and then trying to go deeper and understand them, and suggest them like plots within this kind of simplicity of structural space.

Your work seems to encourage the viewer to become an observer – not only an observer of the world that surrounds them, but also the observer of their own life, their own actions.

Yeah, exactly. Another thing that I do, especially with the works that you have seen in the gallery, is that I build up the scenes. I stage the scenes in real life in the studio, then I start observing them, and then I do the paintings. Which is a very classical way, you know – it comes from very long ago. What is interesting for me in the works is the light. I imply that the light is coming from somewhere else. You never see the source of the light, but when you see the painting, it looks like the light is coming from where the viewer is standing. That maybe implies is that the viewer is the light source. Maybe the viewer actually lights the scenery, which means maybe the scenery is in the viewer. I am trying to show an inner space, a space of psychological structure.

I think that’s an interesting point of my work because I’m not trying to show them something that is somewhere else or is happening elsewhere; I’m trying to show them something that maybe is happening inside of them. Not necessarily telling them that who you see in the picture is you. This is a different story; I am trying to show them that this situation is inside you regardless of who is depicted in the image. Which means that actually, the viewer contains the situation that they see in front of them. So it’s a little window to the inside. That’s one of the goals of the work, which is a bit metaphysical, but I also think it’s very physical if you refer to psychoanalysis. People like Carl Jung, for example, and the idea of culture that exists at a DNA-level inside every human being. This is the discourse that I’m trying to develop here.

Jannis Varelas. Exhibition "Salted Milk, the Fire is Blue" / Camouflage. 2022. 250 x 220 cm. Photo - Courtesy of Galery Krinzinger

In reference to Jung, you have a work titled Anima I, which is also connected to the ideas of Carl Jung.

Yeah, that was my first research on this kind of level. It was shown in the Benaki Museum here in Athens. It was my first try at starting to build structures on the level of the human being as a mirror of a soul. I was trying to create a figuration that implies the existence of a very fluid concept of identity, sexuality, social understanding, and such matters. I was also trying to open a window towards dream analysis as part of our understanding of the world. What is going on when the subconscious enters the cognitive side, which is dreaming, and then what happens when we remember those dreams. So, memory was also a very big part of this research, as in what you remember and how this organises the narration of the world for a human being.

In that show, for example, when I was doing the staging in the studio, I had a small camera and I was filming my models changing their clothes – putting the costumes on and stuff like that. Later, I showed that clip on a big nine-screen video wall, with each screen showing these simple performative actions – like, people changing clothes and getting prepared for their pose. The interesting part was that the viewer would see the models preparing for a pose, and then later, the viewer would see the models in these costumes and poses as actual paintings hanging on the walls. So, there was a certain type of recreating a memory path towards this situation, because the viewer has seen what happened before the making of the actual final product that they are looking at right now. It served as a narrative structure towards describing the memory process.

When I was a young student, I had a book that showed the process of setting up the models in the poses that Caravaggio would then paint – as in, how he would place and move the models, who they were, etc. It was fascinating for me to see the “backstage” of a painting, which is unusual to see. So I also decided to try and show this backstage situation as a memory structure that explains, or at least allows you to go even closer to, the painting itself.

Jannis Varelas. Salted Milk, the Fire is Blue. Installation view. Photo - Courtesy of Galery Krinzinger

Have you experienced states of lucid dreaming? Have you ever experimented with different states of consciousness?

Well, through the path of my life I’ve had certain... not experiences exactly, but ways of trying to understand things through these unclear conscious situations. For example, as a student, because I had dyslexia, I was trying to find ways to remember things that I had read so that I would be able to perform in the classroom. And I found that the best way for me to remember something I had read, or to rewrite something for a test, was through various completely irrelevant situations, like remembering it through the dreams that I had. I would remember a plot and a tree, and then I could connect that to the thing I had read for school, for example. That was a way to recall the information that otherwise would be very difficult for me to access because of the dyslexia. So, for me, there was always something there between the two worlds, you know, between the cognitive unconscious world and the subconscious structure that was right there and somehow holding information for me. And then, through a mechanism of memory, it was deliverable.

I read that you have a large archive of drawings from teenagers who have dyslexia.

Yes, because my mom worked a lot with cognitive procedures for people with dyslexia or other kinds of learning disabilities. She worked at the university, doing research on drawings done by the kids and how they are able to depict reality using certain kinds of symbolism. So, I collected a large archive of their works, and what is interesting is that it was clear to me that you can construct a form of language just by using these symbols and creating a grammar or syntax mechanism. You could express a very complex idea of, for example, social roles or identity issues by just using the language that was encoded in the kids’ drawings. I worked a lot with that for a couple of years, actually. I was doing increasingly more abstract work at the time, but to me it was not a question of going towards abstraction as a general idea of painting – it was just trying to use a coded structure towards showing a certain type of imagery that contains subject matter, like a storytelling structure. It was an interesting path towards what I do now. For example, sometimes I would do a very photorealistic depiction of these drawings; it would look like a very abstract image, but it was made in a very precise way following the exact imprint of the kid’s drawing. It gave me the idea of how you can relate to this very structured, realistic approach towards painting, and to understand that this is a medium and not a cause of the works. Or the work maybe has to do with something else, but the way you’re doing it should be like a discipline that you will use, and that discipline will allow you to go deeper and more precisely into what you want to say. For me, for example, realistic painting is not about actual realistic painting – it is more like an instrument with which to get closer to what my ideas of things are.

Jannis Varelas. Exhibition "Salted Milk, the Fire is Blue" / The Ritual. 2022. 250 x 280 cm. Photo - Courtesy of Galery Krinzinger

You once said that for you, painting as a medium is a very straightforward concentration of energy.

It is, because what you see at the end as a viewer is a huge concentration of effort, energy and time. You see it in front of you, and this is a very straightforward process. Whoever made that for you to see went through this kind of a situation, and I’m pretty sure that a painter can feel this energy going through them, towards the surface, and that’s part of the work itself. For me, if a work is good, as a viewer, I can feel this kind of connection with whoever made it and what I see at the end.

I’ve noticed that sometimes when I look at a work that has technically been made very professionally, I somehow feel that it is almost dead. It’s a very strange feeling, but it resonates with what you said about energy. As an artist, you are a kind of medium and you’re putting all of your creative physical energy, as well as the energy of your subconscious mind, into the painting (or whatever it is that you are creating as an artist).

Yes, and it’s a difficult process – you need to get into a certain zone. For example, for me, when I’m in the studio and I’m about to do a work, I can’t just do it at a routine level. You need to be in a certain zone, and usually what happens is you prepare a lot. You do your things: I stage the situations, I do little sculptures – little things, just to get into the zone. And then I go and paint it. You need a certain type of time management to be able to deliver what you’re about to deliver. I think it’s a matter of discipline; you learn your ways as time passes – you just know that now is a good moment to do this painting, or now is a good moment to start working on something else. Rather than – from nine to eight I have to go and finish that work, and then I’m going to do my other things. I think it’s very important that you listen to the structure of your own mechanism and understand when is a good time for you to go do something.

Jannis Varelas. Salted Milk, the Fire is Blue. Installation view. Photo - Courtesy of Galery Krinzinger

Is there some kind of a ritual aspect to how you reach that zone and how you stay within it?

I think that everyone who works with art and is an artist (or at least tries to express themselves with things that they make) has a type of ritual towards entering this zone. Imagine a dancer – they need to stretch before they start to dance, and they have a certain way of preparing their body to be able to perform in the way that they want to and at a certain moment in time. So it’s the same thing, I guess. It needs a certain type of preparation, mentally and physically. Especially when you need to be standing for eight or nine hours in front of a canvas, because you’re not going to stop when you’re tired – you’re going to stop only when there is nothing else for you to put on the canvas. You need to be able to physically do that. You need to be prepared beforehand so that you can perform as you should. At least in my case, these things are very specific and strict.

Do you ever create in silence, or is there music on in the background?

Sometimes there is music, sometimes there isn’t. Sometimes you need to listen to the work – in a metaphorical way. You need to understand the tempo of what you’re doing. When you’re painting, there’s always a certain tempo that is right there in front of you, but if there is something else around, like music or a film playing on TV, it distracts you from being able to listen to the tempo of the work. Sometimes you need pure silence.

But, of course, sometimes the TV is on – you know, you just have something playing in the background because it gives you a different kind of essence of the space and of yourself. It’s like part of you is forgetting what you are doing, but another part of you is very concentrated at the same time. It’s a very funny and weird situation, but I guess every human being needs these kinds of small distractions sometimes in order to concentrate better.

Jannis Varelas. Salted Milk, the Fire is Blue. Installation view. Photo - Courtesy of Galery Krinzinger

When you mentioned the tempo of the work, it reminded me of a recent conversation with a pianist here in Latvia – he said that when music was performed in the mediaeval period, people had the ability to see its narrative visually in their minds. Nowadays, most of us have lost this ability.

Sometimes a historical perspective can help us understand a lot of things. For example, in ancient Greece, poetry was always accompanied by music because the music would make it easier for people to visualise the narrative. It’s common knowledge, and there are reasons for that. And it’s very important to be able to address these reasons, to understand them and use them, or at least be aware of their existence.

Another very interesting thing is that in Greece, and in the Balkan area, a lot of traditional songs have different ways of pronouncing the words. In older days, there were different structures for, let’s say, writing a poem and the way it was expressed and spoken. The structure gave you what was needed to feel the content of the poem or the song. These are very important technical things, because the structure is what allows you to understand what you’re doing both technically and conceptually.

Looking at your work, it’s quite colorful – there is some irony but also joy. It seems to me that you are quite interested in human emotions. When we look at the six basic emotions that we all have, just one is absolutely joyful. Scientists have confirmed that approximately 65% of our unconscious thoughts are negative. We have to work hard to experience joy at a higher frequency, and I feel that’s something you’re also trying to do with your work.

Well, you know, it’s funny that you say that – the notion of frequency allows you to play a little bit more towards showing what your intentions are. For example, when you use a bright color, it doesn’t necessarily signify happiness. But when you combine colors, you can play with what you want to express; on the frequency level, you can control that because it’s a question of what you put together with what. At the end of the day, the work being happy or sad has a lot to do with colouration. For example, you can have a very odd, weird, vulgar or violent scene, but if it’s been made in a certain way, it can be very appealing. That’s because of the frequencies that are produced from the specific combinations of colors. For example, the old masters, they did that very often – you see a great, violent scene made with really nice and beautiful colors, and the combination gives you a frequency of joy. They created a very interesting contradiction of what you see and what you feel. That is a game that the old masters played, and it’s good to observe it every once in a while. For example, if you go to the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna, you see a lot of these works. Rubens did a lot of that, as did many others.

What is the role of literature in your work? For example, your video installation Aunt Clara’s Place refers to a dream that Allen Ginsberg described in his diary in 1944.

Sometimes I use a book or something I’ve read as a starting point for a narrative structure. I use it as “a common ground”, I’d say. Then I try to put my own input in there and create a new story, or create a new way of seeing things. But I strongly believe that a common ground is necessary sometimes, and, of course, literature is very structural. You can recognise the different kinds of plots and the different kinds of ways of telling a story throughout the years, and sometimes to me it’s very helpful to contextualise the work (or the form of the work, or the general idea of the work) towards either modernity and contemporaneity, or towards more traditional references. Literature, for me, is very useful for placing the work according to the structure of the narration. Whether it is a linear narration or a fragmented narration always indicates which historical era I’m referring to. Because modernity has different kinds of structures of telling a story compared to classical times. For example, sometimes I do a video piece that is very classical in its narrative structure, which can refer to older times or dealing with a subject matter that was relevant at some time in the past, and I’m trying to revisit this kind of concept. Using a very structural narrative is a key with which I can show exactly what I’m doing.

Literature is very important to me also in terms of theme. I revisit stories, for example. I’m currently working a lot with transformative poetry. It’s a very classical narrative structure, and there is this very straightforward, classical form and narrative to address things that have to do with the transformation process of one’s idea of the self.

Jannis Varelas. Salted Milk, the Fire is Blue. Installation view. Photo - Courtesy of Galery Krinzinger

Talking about inspiration, I know that Matisse’s cut-out period has greatly inspired you.

I was looking a lot at the cut-outs of Matisse a couple of years ago. To me, it was very interesting to see them as a way to create costumes for a work. In the beginning, it was very odd because they are very flat, and I was trying to understand how I could make this enormous flatness – that transcends space in a very odd way and, at the same time, is right there – and stage people for my paintings wearing this kind of thing. So, I started making these costumes based on Matisse’s cut-outs. It was very funny because I made cut-outs from fabric or cardboard that could be worn as costumes. But, of course, they were very fragile and they would collapse when placed in the scene – the models would be wearing them, and then suddenly they would collapse and fall off. This collapsing process itself was funny to view – you saw a couple of naked bodies, and on the floor, the cut-out costumes having fallen off in strange formations. I really liked that because it immediately gave me two different perspectives in space: when the costumes had fallen off, they were creating a space in front of the models, and the people who had been wearing them were now looking at them from above. It was very interesting – this kind of by-chance enrichment of perspective in a two-dimensional world. And I use that a lot.

As we all know, art is a language. Do you consciously choose a language that can address almost everyone? Looking at your work, it somehow speaks very clearly. At least at the first moment.

I would say it’s a semi-intentional situation. I mean, I always wanted to create this kind of structure of things that allows you to see very clearly what is going on. But, of course, you cannot really control it. Within the process of making a work, things happen that you didn’t expect, and you can go a bit off of the track that you had planned. But as a general idea, the intention is always there. I try a lot of things through research and, let’s say, strategising the way I’m going to work towards creating a clear line of understanding.

Jannis Varelas. Salted Milk, the Fire is Blue. Installation view. Photo - Courtesy of Galery Krinzinger

Recent years have been overshadowed by the refugees crisis, the pandemic, and now war, and a lot has been said about the role of art in times of crisis – about art as a healing tool. But how do you feel when it comes to real life – does it really work like that? Does art really have the power to change anything? I remember The Restless Earth exhibition curated by Massimiliano Gioni in Milan in 2017, which addressed the theme of migration. This summer I went to Statecraft (and beyond), curated by Katerina Gregos at EMET in Athens, the group show exploring issues of democracy, citizenship, rights, inclusion and exclusion. And I had a strange after-feeling – there were artworks that had obviously been created with the right intention, but somehow, they just didn’t work.

Well, I think this is a big issue, and the way I see it is like a looping situation. The problem comes back again and again – maybe sometimes in different forms – but I think as a society, as a whole, we are always trying to deal with the same question. And the question is how to make a profit. As long as societies deal with everyday issues on the basis of how can you be productive and make a profit, there will always be someone who has to suffer for it, someone who ends up being fucked up by these actions. And that is what creates poverty, hunger, war, refugees, etc., – all of these tragic problems.

Yet we see that art that addresses these issues in a straightforward and political sense is trying to either highlight the specific problem or propose solutions to the specific problem, but it never addresses the issue that is the source of all these problems. And it’s an issue that has been in this world for, I don’t know, thousands of years. Which is why especially with this type of work, I believe that the more poetic the approach, the more rich the outcome is for the viewer. That’s because poetry does not answer questions – rather, it poses them. Works that pose a new question are the ones I find interesting. But works that try to deal politically with a situation or issue (i.e. that address the same urgent matters like trauma, pain, etc.), they continue to go around the question of profit, and so they will never come to an answer. Because a structural thing as strong as profit-making can only be addressed with a structural solution. So, how could we make things function without the idea of profit? If you find a way to do this, then you’re solving the problem. But you need an economic theory that explains that. Photos with people carrying posters emblazoned with calls for freedom doesn’t solve this problem. I find it sad because it’s a very shallow approach to the problem.

If you go to a historical museum and look at old master paintings, all those same things are there, yet they are addressed in a very poetic way. That can give people an idea of how art could address these matters. Of course, don’t get me wrong, there are always variations of form and ideas about how you can work. To me, the medium doesn’t matter. What matters is the viewpoint of the artist: what kind of question are you trying to pose? Or, what kind of question are you trying to answer? I think posing questions is much more interesting politically than trying to answer them within the framework of the arts. Sometimes the subject matter is so heavy that you just cannot work. Especially in Greece; you know, we had many people drown in the Aegean Sea last year. It’s a very tragic thing. You feel that you should do something about it, but even to just say something about it is heavy. For me, it’s very problematic. Sometimes I cannot react much because the sadness that overwhelms me from knowing these things is way stronger than any expressive idea.

Jannis Varelas. Salted Milk, the Fire is Blue. Installation view. Photo - Courtesy of Galery Krinzinger

Yes; it seems that, as humanity, we have been in this loop constantly for many thousands of years, and it is just repeating itself in different forms. Maybe that is our destiny – as a species, we will never get out of it.

I don’t want to be pessimistic, but it seems that we’re looping again into the same situation, the same vulgarity and the same problematic structure, which is: one group is doing something against another group over here, and immediately, completely something else or a completely other group is directly or indirectly affected through these actions in a very bad way, and people end up losing their lives.

To close our conversation, are there any new exhibitions or projects that you are working on now?

At the moment I am working on a large scale installation commissioned by the Onassis Foundation for the lobby of the Onassis Cardiac Surgery Center, while I am also traveling back and forth to Basel for the rehearsals of the play Vergeigt. I am very happy to work with actor and director Herbert Fritsch on this fascinating project.

Title image: Jannis Varelas. War faces / The Revenge of Noh. 2022. Video still / Exhibition "Salted Milk, the Fire is Blue". Photo - Courtesy of Galery Krinzinger