Lessons of the Socialist Anthropocene

Santa Remere

An interview with art historians Maja and Reuben Fowkes on the decolonial ecological perspective from the Global East

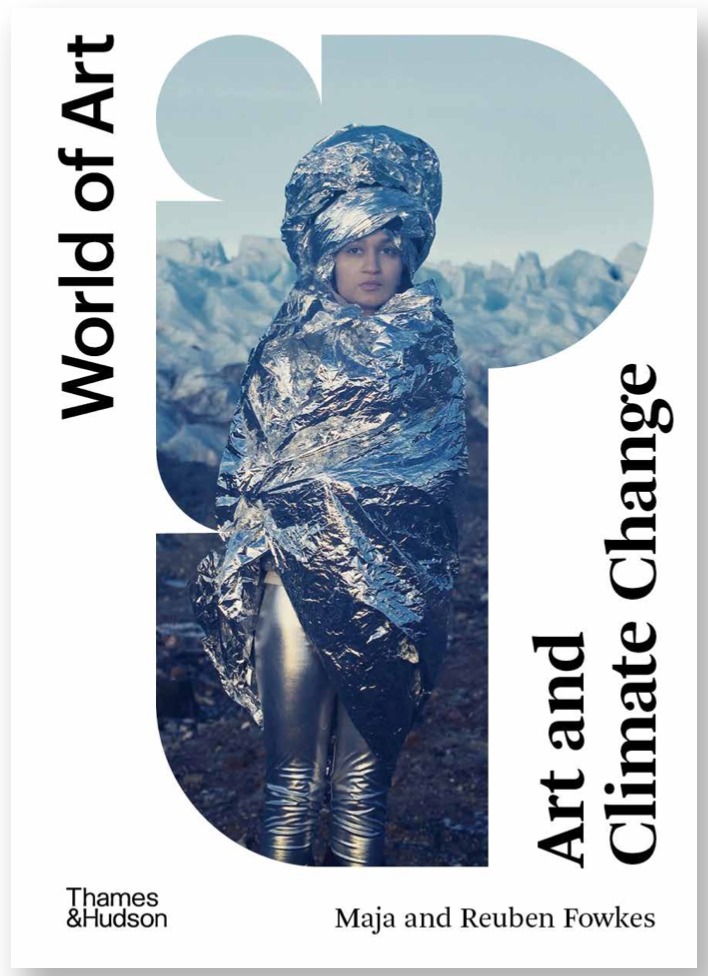

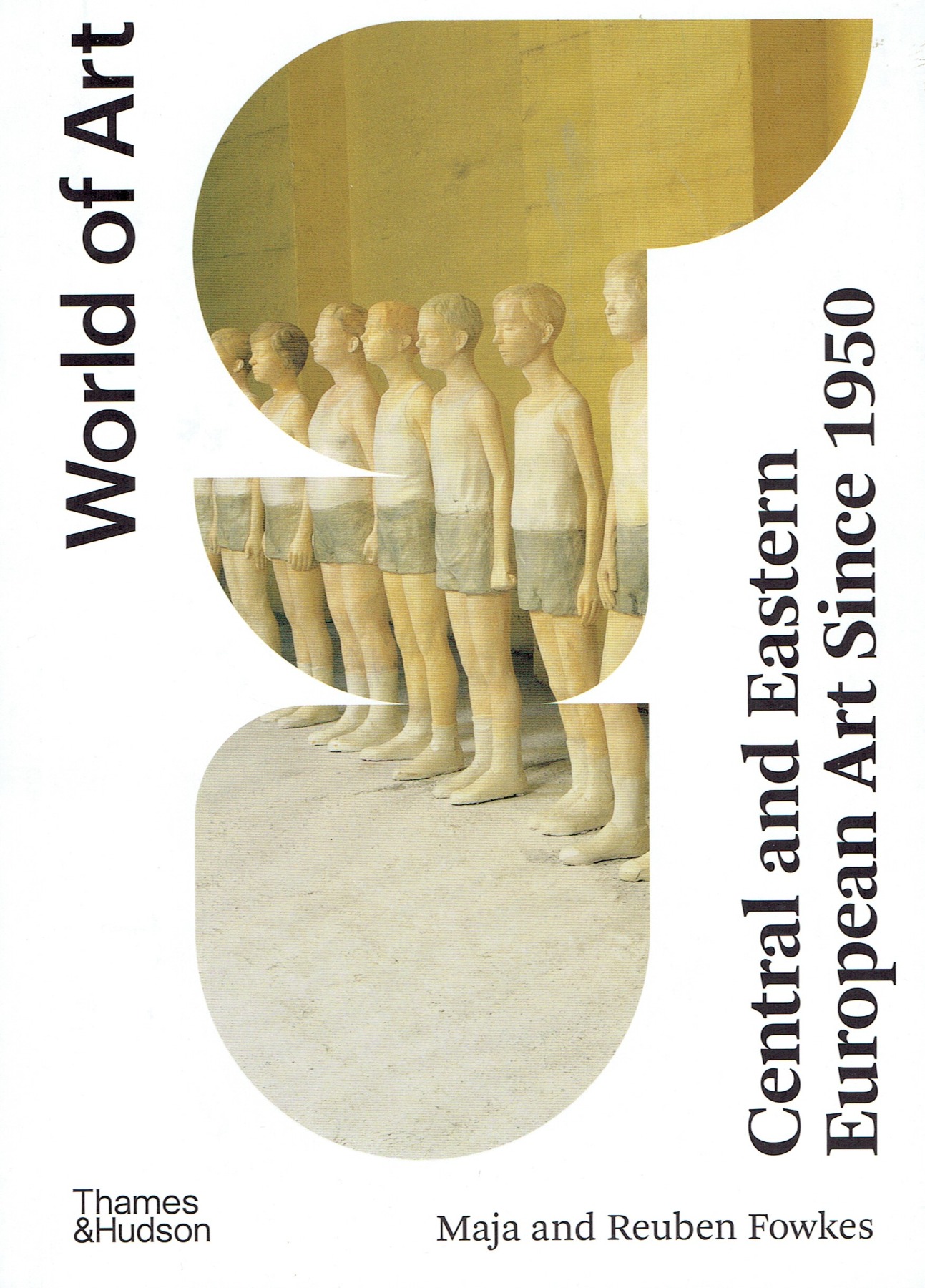

Maja and Reuben Fowkes are London-based curators, critics and art historians specialising in East European art history and contemporary art and ecology, co-directors of the Postsocialist Art Centre at University College London, and founders of the Translocal Institute for Contemporary Art, a platform for transnational research into East European art and ecology that operates across the disciplinary boundaries of art history, contemporary art, and ecological thought. They recently published the book ‘Art and Climate Change’, a collection of a wide range of artistic responses to the current ecological emergency. On January 10, at Riga Art Space, the Fowkeses presented the talk ‘System Change not Climate Change’ in which they analysed the Socialist Anthropocene and its relation to the natural world, ecology and climate change, and how a decolonial ecological perspective, especially one rooted in the non-capitalist histories of actually existing socialism, could sharpen the critique of green capitalist proposals for incremental adaptation to climate change.

As evidenced by the exhibition Decolonial Ecologies at Riga Art Space, reflection on decolonial approaches regarding Eastern Europe and the post-Soviet region has gained new urgency with Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. This subject has been a central component of the focus of your research for some time now. When did you first become interested in it?

Maja: As I am Croatian, the region has always been part of my identity and field of interest. And when I started to work professionally as an art historian, the questions of regional art history and contemporary art were a central focus of my attention – specifically, researching the comparative art history of post-socialist Eastern Europe.

Reuben: I was born in 1971, so I was 18 in 1989, which meant that the fall of the Berlin Wall and the system change around that year really felt like a huge moment in my life as well. I travelled a lot in Eastern Europe, and my interest came from a personal engagement in the changes around then. For me, it was particularly the question of monuments – public monuments and statues of Soviet liberators and Stalin, the new man and woman of the Soviet utopia, and so on – that I ended up working on and which eventually became the subject of my PhD thesis.

Maja: Yes, but it’s not just about our biographies. We were based in Budapest for a long time, and as non-native Hungarians, we experienced some of these issues of post-coloniality and decoloniality in a different light there. And when we started to think about what it actually means to decolonise these kinds of art scenes that existed in post-socialist countries, it was clear to us quite early that it is related to the question of minorities. It’s a question of Roma art, about who has the right to represent a nation state, and how you deal with non-native artists in particular art scenes – how they are included or excluded from these narratives that are often very nation-oriented. In that way, we started to deal with aspects of colonialism long before it became a pressing issue. At the same time, post-coloniality, as it’s defined within the Western and post-colonial theories from the Global South, can be problematic in relation to Eastern Europe because the historical experience here is different from the colonial relations which existed between the colonial powers of the West and the colonies and post-colonies in the rest of the world. Eastern Europe doesn’t easily fit into post-colonial categories, but decoloniality, which means the unravelling of a multitude of exploitative relationships, is much more relevant.

The war in Ukraine (and this is what the exhibition starts with in Riga) has brought these questions to the forefront – what is happening in the territories right now and how it is having incredible consequences on humans, environments, animals and everything, but also the wider cultural and epistemological consequences. And these kinds of decolonial questions that Ukrainian academics and artists are asking at the moment are very, very important. I think these discussions will have wider resonance also in other territories of the region. Questions about post-coloniality and decoloniality in the Soviet Union also arise in the context of Central Asia, Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, etc. – all of which had a very problematic relationship with Moscow. But the Ukrainian question has brought this to the forefront.

Reuben: What’s becoming more sharply delineated is the extent to which the history of the Soviet Union also had this kind of colonial dimension within it, with the continuities of Tsarist colonialism within Soviet structures, mentalities and attitudes – that’s something which complicates attempts to think about those histories again…

Maybe that’s another question… but there are two aspects: one is the issue of decoloniality that makes us think about the colonial elements within the Soviet project as it expanded geographically over different countries – including Latvia, the Baltics, and the rest of Eastern Europe – after 1945. And the other question is to think about how – although the East European countries were neither colonised by the West, nor were they active participants in Western colonialism as it affected the Caribbean, the slave trade, Africa and so on – there was a kind of mentality or colonial thought process, or attitude towards other cultures and peoples, which is still present quite strongly within Eastern Europe. And that’s where decoloniality and an attempt to address and challenge some of these stereotypes and attitudes is also important.

Polish-American researcher Jacob Mikanowski published an article some years ago stating that Eastern Europe owes its existence to the intermingling of languages, cultures and faiths. In the 17th century, Vilnius was a multicultural city with six languages spoken in the streets, and Mikanowski says that the region may have functioned as a gateway between and among different cultural and religious traditions. [He also draws attention to the fact that some Eastern European epic poems, for example, the one from Croatia and Hungary about Nicholas Zrinski, existed before Milton’s poems. He even refers to Larry Wolff, who says that Eastern Europe was created (by French intellectuals) as a flattering foil for Western enlightenment.]

Maja: Yes, it’s interesting to think about the longer histories of the region and the multiculturalism of Eastern Europe as they existed in the period before the 20th century. And it was incredibly multicultural; for instance, Transylvania in Romania was one such historical hot-spot, and even today you can find multicultural traces surviving and thriving there. And there are also our personal histories, again: when Reuben’s great-grandmother came from Lithuania to the UK in the early 20th century, she spoke seven languages and was translating for her people to help out with communication.

What came first, who was first, who invented what – is an interesting question because we’re used to the assumption of Western dominance, which derives also from the supposed victory of the West in the Cold War. We have heard ‘America first’ a lot recently in politics, and in art history there is also this idea that America was first, the West was first, and everywhere else is belated. Actually, even if there were no archives (but there are archives, and there is evidence), such kinds of dominant narratives no longer hold water because there is no such thing as belatedness in other parts of the world. It’s just that the dominant worldview overshadows all the other territories. And this is also the case in Eastern Europe.

We have not done much work on this kind of longer history of Eastern Europe. We look at art history from post-1945 to the present, dealing with what happened to this part of the world during the socialist transformations and afterwards. But there are art historians, such as Katarzyna Murawska-Muthesius, who published a book about the visual aspects of Eastern Europe through maps, discussing the stereotypes of the region and the questions that you just asked. In it she reveals complex issues around the stereotyping of Eastern Europe from the point of view of the West, and how long-lasting these prejudices are in the West.

Reuben: I think this vision of a multicultural Eastern Europe can also be a positive resource to look to, and maybe when you think of some more negative stereotypes and images, and the monoculturalism and populist nationalism of the present moment, that’s something that can be turned to historically as a source of other models – very fruitful and important examples of cooperation between communities.

Could you expand on the focus and purpose of the Translocal Institute, which you founded?

Maja: Translocal started as a platform when we began to collaborate together working in the context of Hungary while being Croatian and British, e.g. working in a non-native environment of Eastern Europe. What was different compared to the previous experiences of people with similar biographies was that usually, especially in Hungary after 1956, once you left, you couldn’t come back – you became an exile. Post-1989, you didn’t have to have this kind of ‘forever choice’ over where you belong. It seemed to us that this possibility of belonging to more than one locality is something that was of the moment, and that there was a real possibility that you could live and work in that way – keeping connections, working in more than one place. A lot of artists have done the same – being based in Berlin, for instance, and keeping a connection to their native countries as well. And this is where we started – documenting our activities through this platform, through public events, through curating exhibitions and other things we were doing. And at some point, the Translocal Institute became a real space.

We specialised in art and ecology and Eastern European art history, with a library and public events, and collaborations with universities in Budapest (especially fine art students and curatorial students) and with the Central European University. For five years, it was a very exciting period for the Translocal Institute, but the political situation in Hungary and in the UK overtook these kinds of translocal realities. Because on the one hand, Brexit forced British nationals to decide where they were going to be based. And on the other hand, Hungarian politics also changed a lot. The Central European University was expelled from Hungary and moved to Vienna, things started to change, and we had to make some decisions.

If we return to the subject of the exhibition, to the ecological and socio-political situation in our region in relation to the global and local processes of decolonisation, what would you name as examples of processes of decolonisation?

Maja: The unmasking of the exploitative relationship is how I would define them. And these kinds of unequal relationships can be found on so many levels within one society or in relation to other cultures and societies.

Reuben: Also, decolonisation is a kind of shift in thinking that moves away from accepting vertical centralising approaches and towards thinking more horizontally from the inside out and connecting in a more democratic or equal way.

Maja: The name of the exhibition is Decolonial Ecologies, which suggests thinking about both ecology and decoloniality in the same breath. For a long time, ecology was seen as apolitical. For a long time, no one thought that ecology was something political – it was always like, ‘Oh, but the real politics is nationalism, or the real politics is social injustice’, and ecology is not really a political question. But with climate change, with people feeling it on their own skin, with extreme weather conditions, with all the mounting evidence, this understanding has shifted, and ecology has, again, become a question of political relevance. And it’s probably the most political of all the questions and it will turn out to be vital for the survival of humanity, but people don’t like to think about it in that way.

That’s why ecology is a loaded issue also around decolonisation. And what is interesting to think about are these somewhat longer histories of ecology and Eastern Europe around the 1980s, when environmental pollution in the Soviet Union and the Eastern Bloc was so bad, across Bulgaria, Romania, Hungary, Czechoslovakia, East Germany, Poland… You know, the air pollution, the river pollution, all these things. I know that the same was happening in the Baltic countries as well. The 1980s was this kind of moment when people started to protest and mobilise because of ecological pollution. But at the same time, these issues became political and emerged along with questions of national identity, freedom and so on, and these processes could now be viewed as decolonial in relation to the oppressiveness of the system.

Reuben: I think what’s interesting about the exhibition Decolonial Ecologies is that it makes the point that things can’t be kept apart. If you think of ecology and if you want to confront the ecological crisis and the climate crisis, that’s also a question of decoloniality, because its roots can be traced back to colonial extractivism. So, a ‘system change’ approach to the climate crisis means you have to think about and start to unravel these legacies of colonialism as well.

Maja: And in our book Art and Climate Change, we do really bring out these interconnections between colonial exploitation and the climate crisis. Obviously, it’s very connected to global capitalist operations, and this is where we need to think about how totally unsustainable profit-seeking and growth-oriented capitalism is.

It was accepted for some time to speak about the Global South and the Global North regarding these processes, and there is a particular imagery associated with these two worldviews. But in your book and research, you bring a new player – the Global East –into the game. Through what elements, symbols or visual characteristics would you say we recognise the Global East?

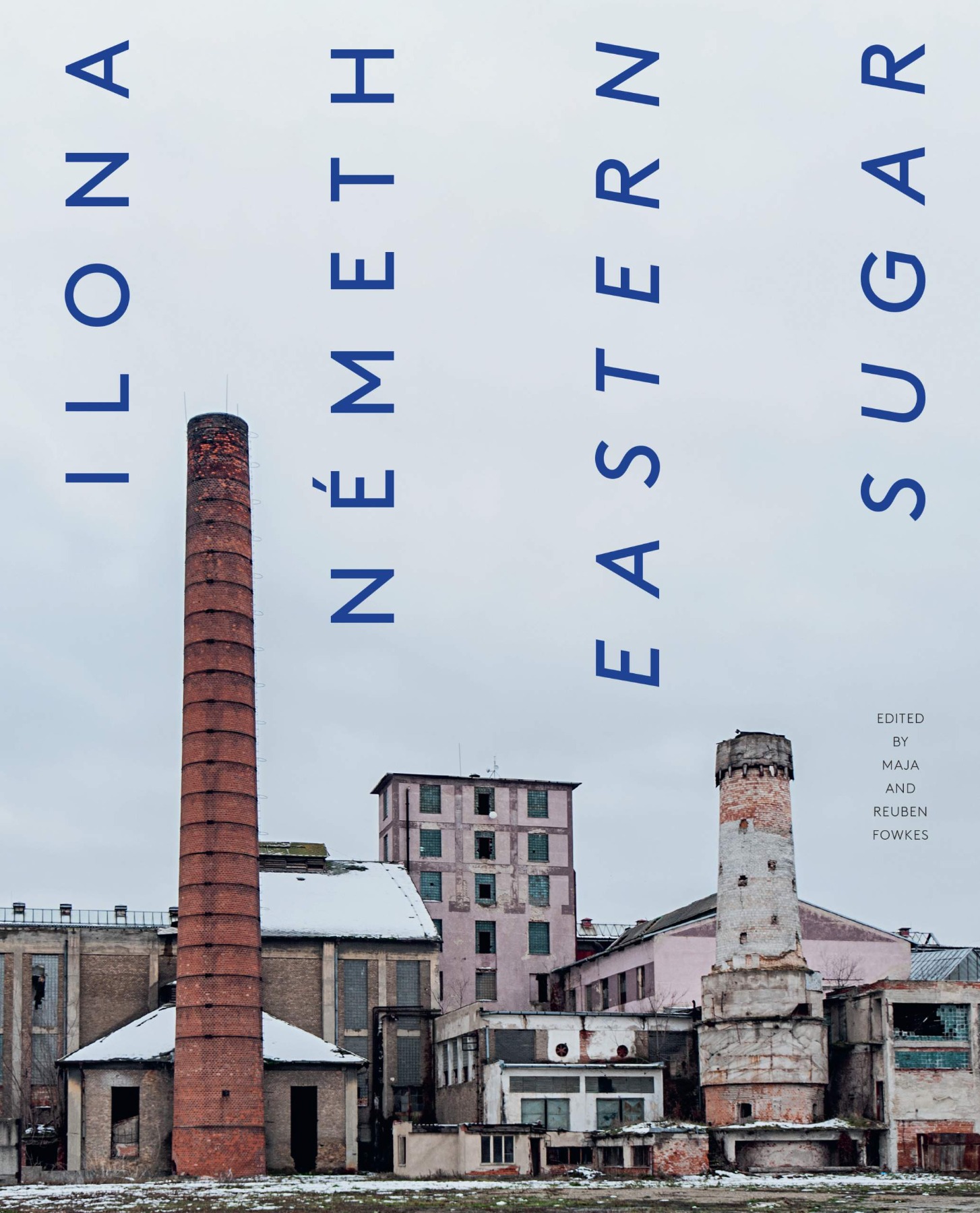

Reuben: I mean, the sort of historical imagery of it would probably be heavy industry. That’s quite a provocative and interesting question, because maybe it can be something else as well.

Maja: And this is why we are interested in what the Socialist Anthropocene could stand for. Although the evidence for the Anthropocene in the environmental history of the 20th century is beyond doubt, the notion has been severely criticised from various points of view.

This includes approaching it as primarily the capitalist way of dealing with and organising nature, and the consequences of that. But then, very potent critiques emerged from the Black Anthropocene, the Indigenous Anthropocene, and from the Racial Capitalocene, dismantling this kind of universalising idea of the Anthropocene. And it became clear again that the East European perspective, or the socialist perspective, is totally overlooked in those discussions. And that’s why we don’t have a simple image of what Eastern Europe is. Is it the floods and the islands which are going underwater in the Global South, or is it the melting ice of the Global North? Where is the imagery that talks about climate change in the Global East? Actually, this is something that we want to uncover through looking at the visual culture of the region more specifically.

Maybe neglected power plants?

Maja: Yes, the ruins of socialism can stand for this.

Reuben: But it could also be related to less visible things that could also represent the Global East or the Socialist Anthropocene. In terms of…

Maja: ...solidarities and uprisings, for instance. Because what Eastern Europe has, and other regions don’t, is an understanding that the system can be changed. If people survived one system and transitioned into the next one, maybe there is a special kind of experience that can become empowering.

Reuben: The end of socialism was unimaginable until it happened, but people survived, continued, prospered and flourished afterwards. And we’re interested in what kind of potentialities can be found in the histories of the Socialist Anthropocene. It’s quite a tricky area, but we think that there’s quite a lot there that needs to be unearthed, researched and worked on.

Did you see the installation Staburadze Corallia by Linda Boļšakova in this exhibition? There was that little mock-up of the rare alpine butterwort, a plant that became extinct in Latvia after the construction of the Soviet hydropower station on the Daugava river. The last individuals of the species were growing on the emblematic Staburags cliff – a geologic feature that appears often in the local mythology as ‘the crying spinner’, a rock that embodies a woman’s spirit on the banks of the River of Destiny. This natural rock formation is now submerged after the hydroelectric damn was built in the 80s. My generation has never seen it. However, this summer a team of divers explored the dark waters near the cliff and re-discovered the butterwort – now as a symbiotic organism that has adapted to life in water. And something...I don’t know...a very deep Latvian-patriotic-feminist-postcolonial feeling arose in me when I saw this work. This ‘flower of hope’ is such a strong metaphor for surviving the socialist system.

Maja: I think that is interesting, and that’s why we think it’s very important to work with contemporary artists. In our research on the Socialist Anthropocene, we are working as art historians, but we are also inviting contemporary artists to work with us over the whole period, because with a contemporary research-based art practice, artists ask questions, they bring connections, and they kind of hit on the unexpected notes that perhaps straightforward disciplinary researchers would miss. Contemporary art can bring these connections very vividly to the fore through symbols, through narratives, and through different aspects that they assemble and, consequently, have a much bigger impact on the whole field.

You can think about the work you mentioned in relation to Latvia as a very site-specific micro-narrative of the plant surviving this terrible transformation of the environment by an oppressive political force. But you could also think about it in more general terms, i.e. as what the Anthropocene has done to the planet and the resilience of nature itself – the plants can really adapt, and perhaps much better than humans. So, it is more likely that the plants, rather than animals and humans, will survive, bringing us to more general issues of survivability and adaptation to climate change.

It is sometimes difficult to have this conversation about climate change with the wider public. In Latvia, for example, we don’t feel the negative effects of global warming yet, and many look at these warnings with skepticism. When activists from Just Stop Oil threw tomato soup on Vincent van Gogh’s Sunflowers, even the most educated and informed part of our society saw it as a disproportionately radical reaction. As researchers, what is your opinion – can these actions or protests actually encourage some amount of change?

Maja: I think there is undeniable scientific evidence – there is no doubt in the scientific community that climate change is happening. There is also a prehistory of climate science in the socialist countries. Back in the 60s, Soviet scientists were in the lead in terms of thinking about the global aspects of climate change.

The science is clear, but there is also no doubt that the oil and petroleum lobby, as well as industry and interests which are very much connected to the political interests in many countries, obstruct climate science from coming through to everyone. It’s a deliberate form of obstruction, and that’s where the problem is. This could be solved by challenging the dominance of these industrial interests across the planet, since it has now become a question of survival.

But activists, artists, scientists, and people in general – there are a lot of people who have become increasingly more aware of it, who make their own choices in thinking more ecologically about food, clothes and other issues...and the festivals that are happening across the world – they also have a role to play in spreading environmental consciousness. You know, change is possible. For a long time, people have been saying, ‘Oh, but one person cannot change anything’, but that’s also just propaganda that tries to stop people from making proactive decisions.

Reuben: Groups like Extinction Rebellion have got very specific theories that you only need to reach 3.5% of people to create change. It’s not that you need to reach 100% – you don’t even need to reach 30%. Their theory is that 3.5% is enough to bring about a tipping point. They give an example of attitudes towards gay people and other kinds of cultural changes and attitudes that have developed and appeared in history. When you reach 3.5%, then you can actually bring about that change. So, you maybe don’t need to worry about reaching every single person, just enough to get a critical mass.

I once wrote an article about the Just Stop Oil protests that took place in London’s National Gallery – I said that as much as I love and admire art, I still support these ‘hooligans’ in their active protests.

Maja: So do we. I mean, are any artworks worth being preserved for a future in which there will be nothing left? And for whom?

You wrote an article titled No Art On a Dead Planet.

Maja: Exactly. Yes. It’s like – what is it for? People don’t really understand the magnitude of the environmental problems and where we are heading.

Theoretician Boris Groys once wrote that art activists want to change the world, they want to be useful, make the world a better place – but at the same time, they do not want to cease being artists who create artworks, a commodity, for the art market.

Maja: That’s his opinion, but I don’t agree fully with that. Obviously, there are artists who want to continue being artists and who wish to take part in the art economy. But there are a lot of artists who actually are taking action at the expense of their own art practice, who say, ‘I don’t want to create more art objects, I don’t want to take part in the international art circuits because they contribute to emissions and the unsustainability of the art’. There are so many artists who are taking drastic actions and not taking flights, even saying: this is no longer about my art production, it is really about joining in and creating more sustainable ways of living and thinking that go beyond just art.

Reuben: It’s not just artists but also art institutions that have been saying, in a way, that there’s no way back. Once you declare a climate emergency, as so many cultural institutions and museums did in 2019, the year of the climate emergency declaration, then you have to follow through. And that changes the way institutions or museums are working – they are trying to reduce their flights, they’re thinking about the environmental implications of acquisitions, for example, asking: should we acquire an artwork that needs a particular kind of bulb that produces huge emissions?, and so on. There is also a shift in packaging – do we need to use large pieces of polystyrene to pack artworks for travel? Can we find more sustainable ways of doing it? Or like the exhibition that we saw yesterday, with the decision to not use plaster boards to make the divisions in the exhibition. All these things are happening not just in a symbolic way, which is also important, but actually in a quite practical way, too.

Hopefully, Groys’ quote is now outdated. But aren’t these kinds of artists and attitudes that you described coming more from the UK at the moment?

Maja: No, I’m thinking of Slovak artists. I’m thinking about Hungarian artists. I’m thinking of Diana Lelonek, who is in Decolonial Ecologies and who we invited to speak in London – she came by train from Poland as she didn’t want to fly. So it’s not just Western artists.

Let’s end our conversation on that positive note.