Naturally inclined to generate images

An interview with Kevin Eason

Kevin Eason (b. 1978, Rustington, UK) is a Swiss-based British artist. Eason produces work in a variety of media including photography, painting, film, drawing, text, sound, and electronic media. The artist has cited a diverse range of influences and sources, including news stories from the internet, satellite imagery, data streams, screengazing, modern accelerators, and environmental concerns. Eason’s artistic practice is often technically complex and, at times, unconventional. His artworks have been described as thought-provoking, time-honoured, speculative, and emotionally engaging. In the late 90s, Eason studied painting and drawing at Northbrook’s Union Place under British painter and poet Gary Goodman. In the early 2000s, he studied photography at the University of Brighton and was a student of Spanish photographer Xavier Ribas. After his BA, Eason maintained his artistic practice, exhibited, was published in Kilimanjaro, worked on community projects, and spent more than ten years meticulously engineering and building a custom camera apparatus.

For many years, Eason lived in Brighton and Hove before moving to Berlin in 2014. Post-Berlin, he returned to the UK before moving to Switzerland in 2017, a country that he has annually visited since the late 90s. From 2019 to 2022 he was enrolled in the Contemporary Art Practice master’s program at HKB (University of the Arts Bern).

Kevin Eason has exhibited in group shows in London, Brighton, Eastleigh, Hove, Palma, Zurich and Biel/Bienne. He currently lives and works in Switzerland.

Eason was recently listed in the publication ‘99 Future Blue-Chip Artists – 2023 Edition’, which will be distributed among collectors and gallerists through major global art fairs (Art Basel, Frieze, The Armory Show, TEFAF). It is a project by Artsted that arose from the urgent need within the contemporary art market to find ways to support a new generation of up-and-coming artists while bringing their vision to a wider audience of collectors and art lovers.

I feel I should mention that this conversation took place because of the importance of Kevin’s way of thinking at this moment of time – his art practice strongly shows knowledge, calmness and love, the most crucial characteristics for being a truly contemporary artist!

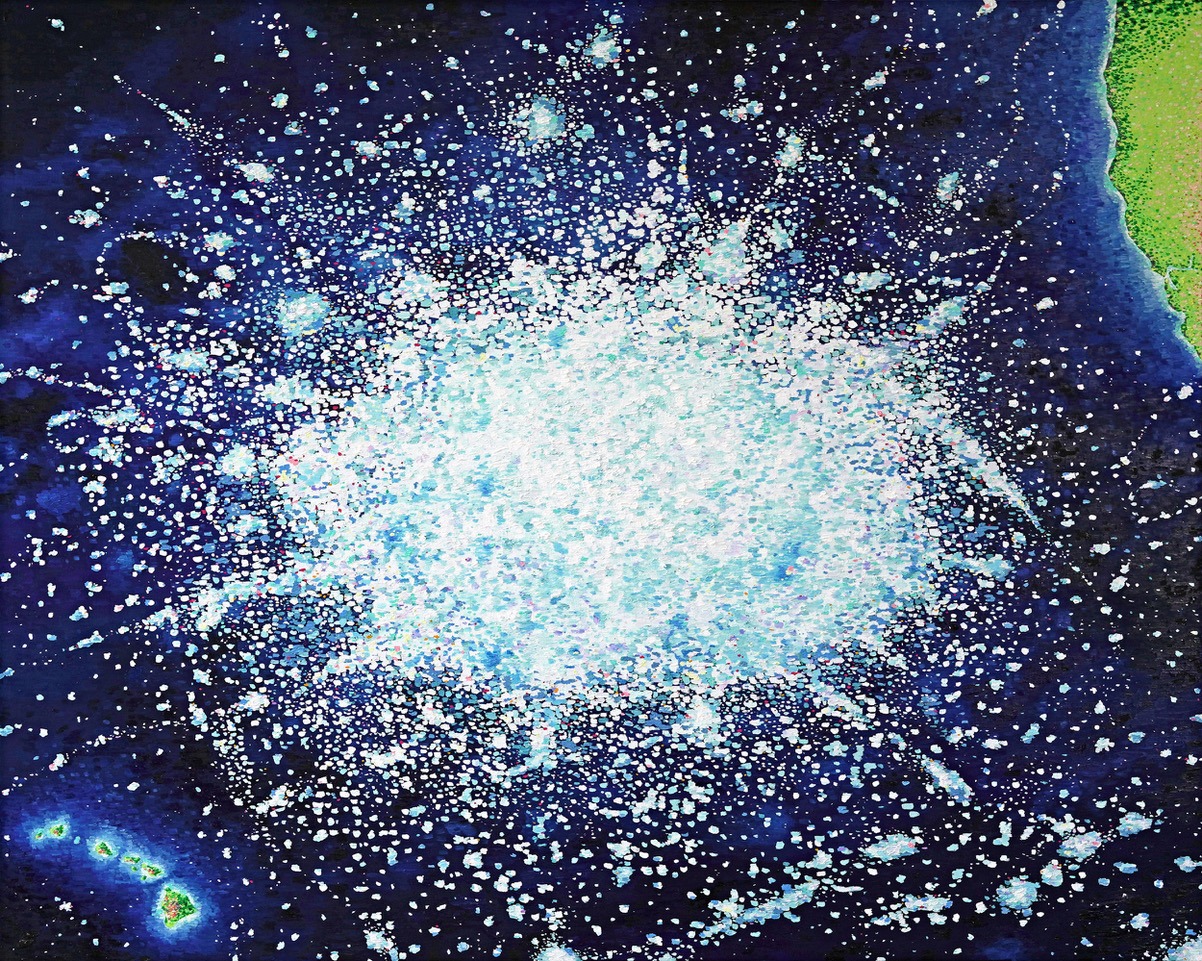

Pacific Trash Vortex 2022, video still © 2023 Kevin Eason All Rights Reserved

Could you tell us about yourself?

I’m a visual artist. I sense and interpret givens relating to natural and human-made environments and technologies. My sources and references are diverse; they range from environmental concerns, data streams, Internet news stories, the water system, screengazing, love, and modern accelerators. I produce photographs, paintings, drawings, texts, videos, and electronic media.

Instinctively, art is to imagine, morph, filter, refine, make, reach, share, connect, converse, disseminate, and manifest change. I like art that states a position, that operates on a number of scales, that is a sublime witness, that is more substance than hype, that contains a plethora of entry points for the viewer, and that is emotionally engaging, vulnerable, and intimate.

Pacific Trash Vortex 2022, video still © 2023 Kevin Eason All Rights Reserved

Where do you come from and what were your formative influences?

I was born by the sea and grew up on the south coast of England. As far as I can recall, art has always been a central part of my life and it was instinctive. I can remember an early drawing of my family and our home entangled in a spider’s web. Also, an early painting of an airplane on the runway at Gatwick Airport with a graduated blue sky with grey clouds and white highlights. This painting was fundamental – my teacher encouraged me to look at the clouds and observe light, and then we painted the clouds together. I think I was seven or eight years old. I also liked taking things apart in the garage and building new things. I was, for the most part, independent in my ways; I believe I wished to develop a classical understanding of things. I enjoyed failing and succeeding by simply doing. My parents provided a good home for my sister and me. No one in my family was an artist or worked in the arts. I continued to draw, paint, and construct, then I became interested in photography and Super 8 cameras.

Pacific Trash Vortex, 2022, video still © 2023 Kevin Eason All Rights Reserved

Pacific Trash Vortex 2022, video still © 2023 Kevin Eason All Rights Reserved

How did your relationship with photography and the fine arts develop?

I wanted to understand more about photography. So when I was 16 years old, I cycled to the local library and borrowed a book on practical photography. This was before Google, and one of the chapters in the book was ‘How to Build a Darkroom’. A few months later, and with the help of my father, we constructed a black-and-white darkroom in the attic. It was incredible – at 16 years old I began processing my own black-and-white films and using an enlarger to print photographs. My darkroom was dusty as hell and it had no running water. I printed long into the night, and I had to take my prints down to the bathroom and wash them in the tub. I loved it! Two years later, I had my first exhibition at the same library where I borrowed the book.

In the mid-90s I attended Union Place to study Fine Art. Union Place was our little Black Mountain. I met Ben Wrapson there; we had some great times together. Nowadays Ben is Head of Sculpture at Goldsmiths. I found some super nice photos of Ben the other day – playing his piano-table sculpture hanging from a tree. The photograph was taken in the garden outside of our shared studio at Union Place. I should post it on Instagram. I like Ben’s early sculptures.

Post Union Place, I applied to the University of Brighton to study fine art photography; my application was rejected...not for the first time. So I continued painting and making photographs, and travelled in Europe with Ben. Then the following year I re-applied to Brighton, and was accepted. The art school had a good BA with some great professors, including Xavier Ribas, Mark Power, Judith Katz and Jim Cooke. During this period I started to print colour photographs. Martin Parr, Gerry Badger, Esther Teichmann and Richard Billingham would visit and give talks. It was great! It was a cool time for photography – people were still shooting analogue, and digital photography was in it’s infancy, so no iPhones or Instagram at that point, just Mamiya’s, Hasseblad’s and Yashica’s...the Cruel and Tender [exhibition] at Tate Modern...super nice.

You mention Garry Goodman and Xavier Ribas in your bio. Were they very important people to your development as an artist?

Yes, they were. Gary and Xavier are both worth their weight in gold. Gary Goodman was my first mentor at Union Place and was a formative influence. Since childhood, I had not spoken with anyone about art on an expansive level; I had just produced work in solitude. I remember having my first crits with Goodman; he was super supportive of my work. We discussed my early text paintings, the five chambers video, and the St Ives sketchbooks. I love those sketchbooks. At Brighton, my mentor was Xavier Ribas. Xavier is a great photographer; he also has a background in anthropology. I have a lot of respect for him – he has continued to maintain his integrity and vision for many years. Back then, Xavier and I had super constructive crits regarding the Passport Portraits and Landscapes Portraits that I made in Switzerland. Then I started to experiment heavily; I think Xavier was a little concerned when I went off-piste and started developing the long landscape and seascape photographs because my early exposures were horrific, and all my output was spiralling and failing at this time...but I did not give up on the idea, as I could see a glimmer of realisation upon the horizon. At this time, Xavier described my rather unconventional approach to photography as akin to ‘boiling an egg in a coffee percolator’. After several months of failing, I did eventually manifest what I had envisioned, and thus managed to ‘boil a few rather lovely eggs’ in my own rather fucked-up ‘coffee percolator’. Afterward, Xavier and I laughed about it. I miss his laugh and he has a great laugh. So, in short, I’m stubborn, passionate, hardworking, and extremely loyal to my ideas. An idea is an intimate relationship, and I love them as I do the people in my life.

You have a nice studio – could we look at some work?

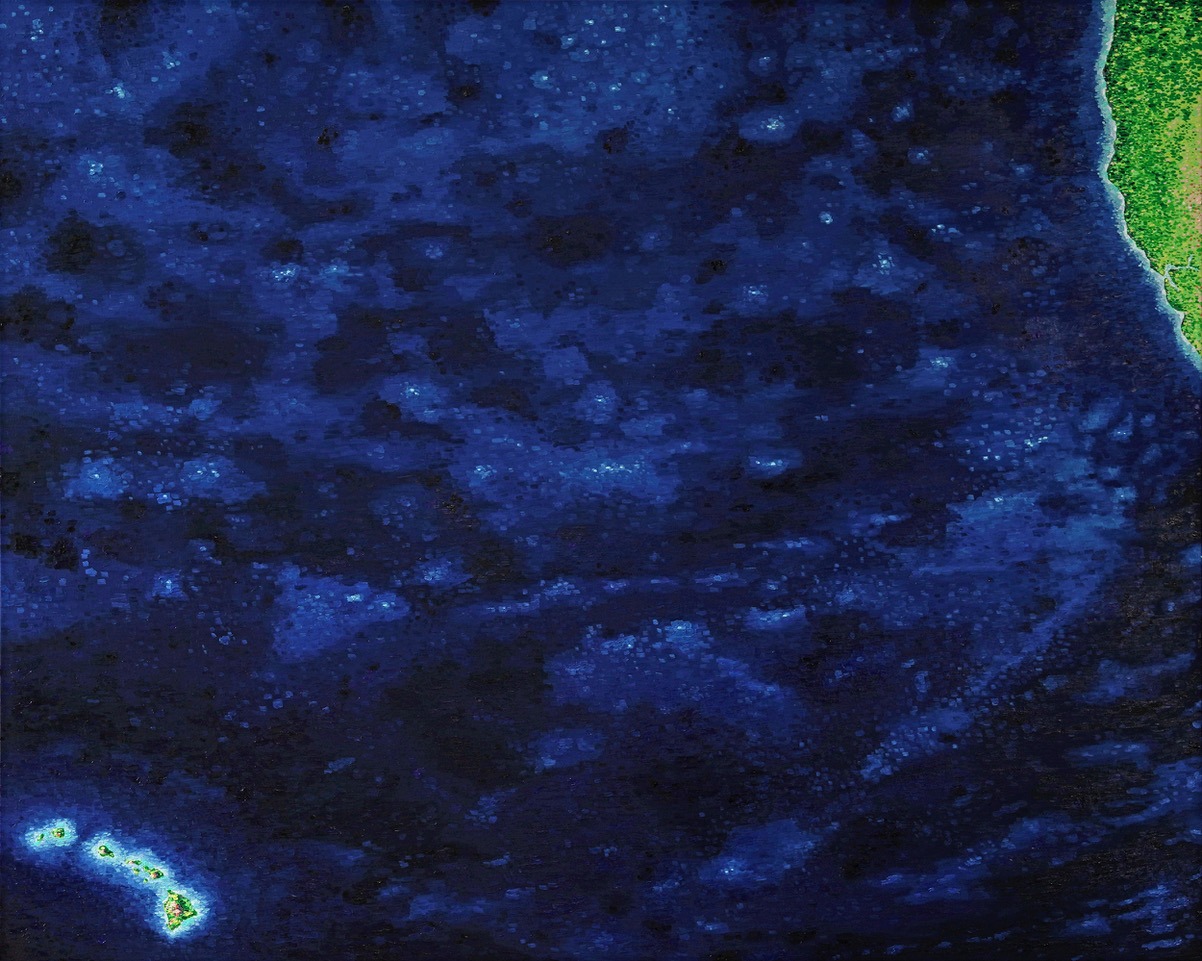

Thank you, it’s a humble little studio. A good studio is so important; so is good light – the studio has four big windows. Since 2019 I’ve put a lot of positive energy into the space. When people visit, they seem to like the studio; they seem calm and relaxed here, which is good. Before here, I was working in studio 310 at Schwabstrasse, Bern. I have great memories of that studio, 310. Yes, let’s walk through the studio together, albeit virtually, and look at some work. On the floor are some preliminary sketches for future works. Over here we have the four iceberg D28 paintings. D28 2019 is the first of the sequence – it is based on published satellite images, whereas D28 2021, D28 2023, and D28 2025 are imagined and set in the near future. The paintings change so much depending on the natural light; sometimes they appear almost monochromatic, and other times they are vibrant incremental steps of blue blocks of ice – white with flickers of cyan. I intentionally used a white that won’t yellow over time. Over here is the Pacific Trash Vortex series; the work is based on the convergence of plastic trash and debris in our oceans. The work time travels between 1860, 2022, and 2042. Over here is a stack of drawings, photographs, prints, and video stills – they range from the mid-90s to the present day. I’m currently in the process of cataloguing the work, and I’m enjoying the process very much. Hindsight is a wonderful thing – so many crossovers and connections between the works that I had not seen before. Sometimes I lay the work out on the floor in a chronological sequence, and a visual timeline is presented – it flows and stretches like a river through the studio.

Could you explain the iceberg D28 paintings and your process?

Yes. D28 broke away from Antarctica in late 2019; it weighed over 300 billion tons, measured 65 km x 35 km, and was twice the size of New York City. For me, it was like a cultural capital of ice set adrift. I was first introduced to the calving of D28 on the BBC and New York Times news feeds, which in turn led me to ESA and NASA webpages, visual references, and research. Also, before and during this time, I was having reoccurring dreams about melting ice and rising sea levels. In the following months, the size, scale, and shape of D28 remained in my hippocampus. My imagination was drifting above the iceberg. I started to make small studies from satellite images. Then I started scaling up and working on the first canvas. I used a colour picker to sample satellite images, which developed the D28 colour palette. I then spent weeks mixing batches of paint for the series. I was deep in ‘Flux-Modus’, tangled up in remote sensing and image sculpting. An iceberg of this size can take only a few years to melt, which is alarming, so a melt window of six years informed the short-term speculative sequence of the four paintings: D28 2019, D28 2021, D28 2023 and D28 2025.

Plastic Bag in River, Zurich, 2018, photograph, dimensions variable © 2023 Kevin Eason All Rights Reserved

Before you had read the news feed about D28 breaking from Antarctica, had you worked on similar themes?

Speculative imaging – no. Environmental concerns and water – yes. D28 was a pivotal moment in my practice. For many years, water had featured in my work, examples being Plastic Bag in River from 2018, The Water Became Red from 2016, Spree from 2014, Seascape II from 2003, and St Ives Seascape from 1996. Before D28, I was not referencing satellite imagery, but I was acutely aware that since modernity, imaging had been drifting away from a more feet-on-the-ground perspective to an overview of us from above, from early aerial photography to satellite and machine vision. Then, more recently, AI-generated imagery; here, I can’t help but think of Trevor Paglen’s Vampire (Corpus: Monsters of Capitalism). For me, it’s the most important portrait of the 21st century, total ‘Goya-AI’ territory. So, real-world news events had not been featured in my work before. This was new art territory for me, yet I touched upon a tangible point of contact, and the flux felt good. It presented responsibility, inclusion, and a short-term speculative projection based on fact and imagination, which I liked very much. Art is alchemy and a primitive operating system, and on this occasion, a conversation between art, science, environment, technology, and short-term projections was manifested in the D28 works. This continued into the You and Pacific Trash Vortex works. I was excited by this alchemy, and people seemed to connect with the work. I believe it did not require too much decoding, which was perhaps refreshing for some.

St Ives Seascape from Sketch Book No 1, 1996, sketchbook mixed-media © 2023 Kevin Eason All Rights Reserved

Ecology and climate change are important subjects nowadays. We all are talking about it, but it is good to do the research and put the data on paper…

Dissemination of information is key, and that information can be in the form of raw data, news stories, social media posts, artistic responses, and protests. All of these carry equal merit, are able to transmit the importance of raw content to a global audience, and manifest change for the greater good. My research and data were manifested into images which could have easily become a text or performance. Yet, as a visual artist, I would say that I’m naturally inclined to generate images. ‘To see’ is about 200,000 years old, and our first paintings are around 45,500 years old, whereas writing is said to be around 5,500 years old. So, seeing and image making are older than written language. As a visual artist, I guess I’m old fashioned – a contemporary traditionalist, possibly...maybe. It excites me to think about the evolution of seeing, shifting perceptions, and images that humans have generated and will continue to make. They inform us.

You mentioned reading whilst working on the D28 artworks. What kind of literature were you reading?

A mixed bag, really… Phenomenology Perception by Maurice Merleau-Ponty. The book is a masterpiece. If I were to describe Merleau-Ponty as a painter, I would say Cézanne, another true master. I read Ramblings of a Wannabe Painter by Paul Gauguin multiple times. Ramblings was the last essay he wrote before he passed away. There is a passion in his writing which I admire; he states a position, and I like that. Glitch Feminism by Legacy Russell; essays by Arthur Danto. Also, whilst in Sadie Plant’s seminars, we would dip into Donna Haraway, Bruno Latour and René Descartes. The Fountainhead and Atlas Shrugged by Ayn Rand; I’ve read both several times, both – masterpieces. Nothing If Not Critical and Rome by Robert Hughes. Oh, Hughes… 100 Artists’ Manifestos From the Futurists to the Stuckists, selected by Alex Danchev. After the Ice: Life, Death, and Geopolitics in the New Arctic by Alun Andersun. I really enjoyed After the Ice – so informative. I am a regular on the NASA and ESA webpages. Researching icebergs on Wikipedia. Encounters at the End of the World by Werner Herzog… I love Werner – as an artist we must pick those locks! I was also listening to field recordings of Antarctica, often looped for several hours or days at a time. In my mind, my studio walls became melting ice walls, and I was painting deep in an ice crevasse, a chasm ice plateau of the mind.

D28 2019, 2020, oil on canvas, 140 cm x 140 cm © 2023 Kevin Eason, All Rights Reserved

D28 2021, 2021, oil on canvas, 140 cm x 140 cm © 2023 Kevin Eason, All Rights Reserved

How does your practice and the intimacy of the studio reach the public? What was the reaction after the D28 paintings were published on the BBC World News homepage?

In the studio, one is emotionally entangled and deeply involved with content and process. The work is in a constant state of flux. It’s an endless stream – it’s intimate, and it’s love. Then, at a certain point, you step back from the work, and it is finished. A period of calm follows, and then, if you feel it’s good enough, it’s time to publish the work. But sometimes it never leaves the studio; I experience this often. Because the questions start – is it good enough to add to the lineage of art? My mind wrestles with this question. Does it communicate a clear vision? Does it need too much decoding? I will always struggle with ‘the artist’s doubt’. I concluded that the D28 work had the ability to transmit a message, so I had confidence in sharing the work. Initially, I shared the D28 paintings in Forum A and B at HKB in Bern, Switzerland. Then a few months later, Jonathan Amos and I connected and had a conversation about the D28 paintings. Jonathan seemed to immediately connect with the works, which was great. He especially liked D28 2023. We both agreed that the four paintings should remain together, and should not be split up. I had only been to Antarctica in my imagination, but Jonathan had been many times. He spoke with great passion about icebergs and the iceberg graveyard in the Weddell Sea. He said that he would like to share the paintings with Helen Amanda Fricker, a glaciologist at Scripps Polar Center, and Catherine Walker, an earth and planetary scientist at WHOI and NASA. They both had deep connections with Antarctica and had been involved in field research and predicting the calving of D28. It was so nice that the work was being shared; I liked that. Then around four months later, it was after COP26, I just got an email from Jonathan saying that BBC World News had published the D28 paintings on their homepage. I was so touched! Then I started getting DMs from people from all over the world, from philosophers, artists, writers, galleries, scientists, poets, nurses, school children, and students. A vibrant cross-section of people seems to connect with the works, and many of them said that the artworks spoke to them. I was deeply touched by all the messages, thank you.

D28 2023, 2021, oil on canvas, 140 cm x 140 cm © 2023 Kevin Eason, All Rights Reserved

D28 2025, 2021, oil on canvas, 140 cm x 140 cm © 2023 Kevin Eason, All Rights Reserved

Consumerism has lately been one of the main subjects under discussion, and you talk about the environment. Has this subject always interested and concerned you, or has it become more important to you just recently based on what is happening in the world?

Yes, consumerism and our negative impact on the natural world are of great concern to us all. We need to produce and consume less. I’ve consciously reduced what I consume, and produce less than I did 20 years ago. Such themes have not always been central to my practice; I operate in different zones and am punctuated by different themes and influences. Many of us share the same concerns pertaining to the natural world. I gave up owning a car around 20 years ago. I tend to walk, cycle, travel by train, and rarely fly. I recycle, sign petitions, share content, and support what I believe in. Also, growing up in Brighton and Hove, the local politics were green, and this influenced my outlook. I did not like to see plastic bottles being washed up on the shoreline, nor did I disregard plastic bags in rivers. It’s total nonsense; we need to change our ways of being, we need to protect and preserve precious natural environments because they are more worthy than capitalist profit. We do have some important gatekeepers – such as Greenpeace, The Ocean Cleanup, Greta Thunberg, Sir David Attenborough, Leonardo DiCaprio, UNEP, and 4Ocean – that keep us in check and are instrumental in the dissemination of key information. We know – we really know – what is right and what is wrong, yet we humans do so much wrong. We humans are contradictions; the animals look at us strangely, and we need to work on that collectively.

Has it been easy to forward your artistic message to the people?

Not always. I believe that many artists, myself included, fail more often than we succeed in communicating the complexities of an artwork to a viewer and the wider audience. What I mean by that is, if the manifested work needs too much decoding by the viewer, then the artist runs the risk of failing to connect, engage with, and share the embedded complexities of the work with the viewer. Yet on rare occasions, if the alchemy of the artwork contains, let us say, an aura, then the artwork has the ability to transmit the artist’s raw intent and it has the unique ability to penetrate the soul of another. Intimate histories between artist and audience begin to establish themselves; the artwork is a transmission bridge, a portal where intimate dialogues commence forth. Arthur Danto wrote about an artwork’s aura and how human senses develop in relation to art. Yes, it’s subjective, yet when one walks into a given situation, and you feel the magnetism of another being, of an artwork, it instinctively transmits a timeless feeling – at times, the transmission feels some 45,500 years old. That feeling, that sensing, will never tire because art is a primitive operating system.

Going back to the arts, I would like to ask you about mediums and techniques, as you have used many different ones. You’ve worked with photography, video, drawing, and electronic media. Why have you returned to painting?

Instinct is my guide; I naturally drift into different zones. Over the years, I’ve produced drawings, videos, photographs, paintings, and electronic media. Ideas are sparks from deep within, yet without commitment, technique, and process, those ideas can fade. I see what I want to make in my mind, then I reverse-engineer how to get there. An instinct theory informs my practice. In the past, I was deeply entwined with photography; its relation to science and art has always appealed to me. There are intimate interplays one must understand and master, relating to specific technical processes, and with knowledge and experience, one has the potential of realising in physical form what one originally envisioned. Over the last few years, I felt that I was spending too much time on-screen, and I missed the intimacy that I had previously experienced in my earlier analogue practice, such as drawing and painting. So, when I started developing preliminary studies of D28, all were naturally navigating towards the canvas, or the cave wall. I’m able to use an analogue or digital brush; I appreciate all technologies and approaches in regard to realisation. When I discussed the D28 paintings with Hans Rudolf Reust, he said that I was an image-maker and an image-sculptor. I like the idea of sculpting images. I always work within a semi-conceptual framework where I insist on giving myself a few rules. The rules are deeply considered. I don’t break my self-imposed rules; I don’t wish to drift out of the frame and move away from the original vision. If I do, things can start to get messy, and then too much decoding is required in post, so I maintain my position. For example, with the D28 paintings, the initial starting point were images from ESA’s Sentinel-1 satellite. Sentinel-1 orbits at 693 km above Earth – this informed my fixed field-of-view and framing, and I could not drift away from that fixed perspective. D28 2019 was based on published satellite images, yet the further three paintings – D28 2021, D28 2023 and D28 2025 – did not rely upon visual references and were instead pure imagination and speculation. I knew that in order to maintain the vision, my imagination had to become Sentinel-1 and track D28 from above, in solitude. So, with that in mind, my imagination and studio became a remote sensor and imaging system where I maintained an orbit of 693 km above Earth. Also, a strict colour palette was another rule. Early published images of D28 were monochromatic, and then within a few days, scientists and researchers started to colour the monochromatic images. I imagine that they have freedom in their colour palette choice. So, a colour space had been pre-determined for me. I liked the idea of operating in a limited colour space, and as a result, it became my colour field. I used a digital colour picker tool and started to collect colour values from visual reference material. I then translated the colour values from digital to analogue values. I spent weeks batch-mixing the D28 master colour palette; then I sealed them in airtight jars and stored them in the fridge. There was fantasy interplay between the Antarctic research station and the artist’s studio that I liked very much – where ideas pertaining to remote sensing, speculation, imagination, real-world events, and image sculpting drifted in the endless ocean of my mind.

Can you tell me about the work that you made after D28?

After D28 I started working on You (Artist’s Screengazing Elicits Recall Flow Phenomenon). You navigates through the intimate space of an artist’s studio, the screen, and the invisible space between human and screen, where silent filters exist. You utilises a hybrid form of the ‘method of loci’ technique, also known as the ‘memory palace technique’, to build a mental framework which directs the flow, stream of consciousness, and modus operandi of the realised work. As one screengazes, one does not typically vocalise thoughts. In You, the stream of consciousness is vocalised, recorded, and uploaded into the information age. The work drifts in fields of memory, interpretation, remote sensing, and imagination. In an early presentation of the work in Forum A in Bern, Andrea Gohl said it reminded her of the stream of consciousness in Ulysses by James Joyce, which was first published in Zurich over 100 years ago. This was great feedback from Andrea, and this helped me a lot.

As an artist, when you are going through this process of making work, you are thinking and processing so much, like a super-computer. One is working in the studio for months at a time. Quite often I’m in solitude. It is a very intimate experience, but the thoughts pertaining to the work dive deeper and deeper – the artist is a submarine. In You, I wished to document my deep dives. In You, I screengaze into digital stardust, into a photograph taken in Basel in 2003, and zoom into pixels of digital reproductions of the D28 paintings. You is over eight hours in duration – it’s not for the fainthearted. I’ve posted a few extract reels on Instagram. After that, I began working on the Pacific Trash Vortex paintings.

Pacific Trash Vortex 2042 (North Eastern Vortex), 2022, oil on canvas, 120 x 150 cm © 2023 Kevin Eason All Rights Reserved

I’m interested to hear your thoughts and perception (as an artist) relating to environmental concerns. Could you explain how the Pacific Trash Vortex series was created, and what is the story behind it?

Post D28 and You, I was in an isolated mental state. I was experiencing loss, and I was in mourning. I was deep-diving and felt guilty for being human; we are a highly contradictory species. I started to think about what we as a species give back to the natural environment – very little, I thought. In fact, what we give back to the natural environment is often a negative input into the field. This naturally led me to the largest accumulation of plastic and marine debris in the world, known as The Great Pacific Garbage Patch. Although the convergence zones of trash in our oceans are well known and documented, the conversation had seldom moved into the arts. I believe the subject matter makes many of us feel uncomfortable because we are confronted with the truth of ourselves. Many of us opt for a mental pathway of ‘out of sight, out of mind’. The Pacific Trash Vortex series was about putting the horrific contradiction of us very much ‘into sight and into mind’. I think that many people don’t like the Pacific Trash Vortex work – it makes them feel uncomfortable. I feel it, I pick up on the energy flux. That’s okay, but the work was not manifested with the intent to reside in the safety of a clique of self-serving hierarchies and profit. I’m interested in art as witness. Pacific Trash Vortex is a global portrait of us, and it’s a hard pill to swallow. So, to explain the paintings a little, the three Pacific Trash Vortex paintings are sequential and have a timestamp of 1860, 2022, and 2042. The three paintings share the same fixed satellite view of the North Pacific Ocean. To the bottom left of the canvases one can see the eight Hawaiian Islands, and to the top right are California and the West Coast. North Pacific Ocean 1860 (Two Years Before the Invention of Plastic) is the first painting of the speculative sequence. So, in 1860 we view an interpretation of a trash-free ocean – as it should be, right? Pacific Trash Vortex 2022 (North Eastern Vortex) is the second painting and is an interpretation of trash vortex data and infographics from Wikipedia and internet images. In the 2022 painting, the trash hyper-object confronts us like a mirror – a global portrait of us has amassed and is drifting in the Ocean; it’s horrific and alarming. Pacific Trash Vortex 2042 (North Eastern Vortex) is the third painting – the vortex has expanded and morphed.

Whilst I was in a gallery where the three paintings were exhibited, I overhead some gallery visitors describing the work as a ‘trash galaxy’, a ‘plastic cosmos’, and a ‘virus of waste’. I like that people see the horror in the work; it’s important. We make real-world horror movies. Look around you, they are everywhere. It’s part of our shared history, therefore it should be part of our shared art history. In the works, the vibrant and colourful aesthetic of consumer products is referenced. In the colourful consumer dabs of pixelated paint, a violent beauty and a contradiction confront us. We are the violence contained within the depicted. So, as active participants, one collectively looks down from the satellite to Pacific Trash Vortex and we contemplate our detrimental impact on the natural environment. The paintings take a position as a witness. They stand in the fields of art, ecology and activism, where engagement, discussion, dissemination, and manifestation of global change are encouraged.

North Pacific Ocean 1860 (Two Years Before the Invention of Plastic), 2022, 120 x 150 cm, oil on canvas © 2023 Kevin Eason All Rights Reserved

You have also been researching water. I believe what we experience in childhood stays with us. What do you think?

Yes, I agree. I was born by the sea, and today I live next to a stream and close to a lake. Water, and the ocean, have influenced and directed my life. Water is the driving force of all nature; it is the most studied and least understood substance that we know. 71% of Earth’s surface is covered by water, so yes, I would say that I’m 71% influenced by water. The water system and the circle of life are one; it has the ability to sculpt stone, it constantly reshapes land, surprises us without warning, and flows through all living things. Humans attempt to manage water, but water manages us.

You are originally from the south coast of the UK. You have lived in Brighton, Berlin, Zurich, and studied in Bern. How do you feel about being in different places? Do these places influence you and your work?

Yes. I was born by the sea. As a teenager living on the south coast, I met some Swiss students who were learning English in my hometown; we became friends and would send each other mix tapes in the post. So I started visiting Switzerland in the mid-90s and making photographs and sketchbook studies here. I’ve always felt peaceful in Switzerland. So, yes, one’s geographical locale and environment can inform practice. Nowadays, I would say that the geographical locale influences my practice less, as my recent work originates from the internet, news threads, ideas of remote sensing, Google images, and infographics. Having said that, for some time now I’ve been photographing rivers in Switzerland. I do like to be in different places, yet I’m a homebody, so if I find a place that presents me with a sense of calm, then I’m happy to remain there until magnetism navigates me toward the next place. Berlin was great; I met some wonderful people there. I miss the vernissages at Sprüth Magers, the Walther König bookshop, listening to Elsa play the piano, talking with Jan, and cycling on the runway at Templehof. Post-Berlin, I briefly returned to the UK before moving to Zurich, Switzerland. Then the Contemporary Art Practice at HKB in Bern followed.

It sounds like Switzerland was in your destiny!

It’s a great country. I was born on an island surrounded by water, and people say that Switzerland is an island in the centre of Europe – the ‘water castle of Europe’. I have the feeling that I’m drifting away from everything, going deeper into ideas...far from all, like an exile. On the whole, I feel calm here and I’m productive. In the summer I like to swim in the lakes. The winters are not so easy because things become grey and monotone. I do not suffer from depression or SAD, but some friends struggle with the grey months. Switzerland has been good to me. I’m thankful for the land and its people.

How was your time at HKB (University of the Arts Bern)? Who were your mentors, and what do you think makes a good mentor or professor?

My time at HKB was good; I met some great people there. Not too many egos, with feet firmly on the ground – which is refreshing for an art school. My primary mentors were Renate Buser, Andrea Gohl and Hans Rudolph Reust. I also discussed my work with Thomas Strässle and Sadie Plant. All played pivotal roles in supporting my artistic development. It could have been a single conversation in the studio or on Zoom, or months of studio visits. Renate said that the D28 paintings were political and that I was onto something, Hans said that I was sculpting images, Andrea spoke of speculative projections, and post-The Gallery is Empty-Thomas spoke of the ancient Greek ‘memory palace technique’, which, in turn, helped me on my journey to manifesting Screengaze and You. Stefan Humble, Andi Schoon, and Tine Melzer were also great. For me, what are important in a mentor, teacher, or friend are enthusiasm, constructive criticism, engagement, and passion.

And the main question -- how did you recently become one of the ‘99 Future Artists’?

London-based Artsted had a global open call; I submitted a bio and portfolio. I let it fade, then a few months later I was tagged in an Artsted Instagram post that announced the 99 finalists – that was a nice surprise. Then a couple of weeks later, the Artsted book featuring the 99 artists arrived in the post. It features some really cool work from emerging artists from all over the world. So nice! The publication will be exclusively distributed at numerous art fairs, including Art Basel, Frieze, Artissima, The Armory Show, FIAC, ARCO Madrid, and TEFAF.

I know you are working on your website at the moment. How’s it going?

Super slow... trying to reduce my screen time. Working on a new website is a huge project. At the moment I just have a one-pager bio, some work on Instagram, and a few indexed images on Google. That’s okay for now, but yeah...I know, I need to do more. I will continue working on the website this year, and keep on publishing on Instagram. I have around 25 years’ worth of work to catalogue, and that content will form the website. Progress is not as fast as I would like it to be, but it’s moving. Plato said to never discourage anyone who continually makes progress, no matter how slowly.

Title image: Self-Portrait in front of Pacific Trash Vortex 2022, artist's studio, Switzerland, 2022