Painting is a Time Cluster

An interview with Katharina Grosse on the occasion of her solo show at Bern Kunstmuseum

I first registered Katharina Grosse some 20 years ago as ‘that German painter who is strong enough to compete with male artists in her execution of grandiose-scale work.’ It was enough for me to see her as a Feminist artist. Now, of course, I recognize that her goal was never to compete with the men on a sheer physical scale; her ‘strategy’ was much more complex: to challenge the painting – so central to the male dominated art canon – itself.

Exhibition view. Katharina Grosse. Studio Paintings, 1988–2022 / Photo: © Rolf Siegenthaler /

Kunstmuseum Bern

A show modestly titled Studio Paintings: 1988–2022, on show at Bern Kunstmuseum till June 25, is an amazing overview of the great abstract painter’s lesser known artistic output. The studio works turn out to be not just a mere laboratory of ideas for her large-scale in-situ paintings, but a meaningful piece in the puzzle of her grand view on painting as well as reality itself. Curated by Kathleen Buhler, chief curator of Bern Kunstmuseum, the show displays 42 works that reveal the way Grosse revises and reinvents the textures, shapes, surfaces, and colour combinations in her ongoing experimentation with paints, colours, and her hallmark – stencils and sprays.

This show is part of Bern Kunstmuseum’s series to give a platform to important female artists. With a major expansion ahead, the museum has virtually given the artists carte blanche. Latvian artist Daiga Grantiņa will follow in Grosse’s footsteps in 2025.

So, how does Grosse challenge (abstract) painting? The following points resonate with me the most:

First of all, although powerful, Grosse’s spray and stencil paintings lack the gestural, expressive brushstroke of her male counterparts. Her paintings are decentralized and they avoid subjectivity, instead highlighting rhythm and movement (and their interruption.) Grosse’s canvases and wooden panels almost do not seem like autonomous works. They are more like a glimpse into a larger fabric that goes beyond a single canvas. She stresses the impossibility of the autonomy of an artwork (and hence, the impossibility of ‘the Master’) and our inherent embeddedness in social reality.

Secondly, Grosse upsets the Cartesian view of the mind as being wholly separate from the corporeal body. She goes against the deeply rooted belief that sensation and the perception of reality are thought to be the source of untruth and illusions. Her works, on the contrary, require physical presence and movement for the artwork to become truly alive.

Thirdly, her way of destabilizing painterly hierarchies – by introducing ready-mades, allowing the negative (white) space to dominate, and exposing the walls behind the slashed canvas – doesn’t allow for easy enjoyment. For a moment we are allowed to immerse ourselves in the vivid colour, but just as quickly, we are spit out of the painterly surface by some branch, fence board or unpainted void that opposes the rhythmically repeating lines. In other words, she doesn’t allow her viewer to forget that this is just a painted illusion. She keeps on pushing us back into reality. A reality from which we can never fully detach ourselves and in which we remain embedded. It’s the most radical Feminism – on the verge of Buddhism.

Although oftentimes verging on the definition of installation, and even performance, in her Bern show, Grosse restores her vows with the medium of painting. Her braveness, seriousness, and joy about it confirms her being worthy of the title she sometimes receives: the greatest living female painter.

Our conversation took place in the aftermath of the Bern show opening. We touched upon ideas of Feminism, German Romanticism, Gestamtkunstwerk, Reality/Illusion dichotomy, and other topics.

Exhibition view. Katharina Grosse. Studio Paintings, 1988–2022 / Photo: © Rolf Siegenthaler /

Kunstmuseum Bern

It turns out that having this show in the little conservative capital of Switzerland, Bern, is no coincidence. It was in Bern Kunsthalle – the legendary space where contemporary art was born in 1969 under the leadership of Harald Szeeman – that in 1998 you first allowed yourself to transgress the borders of the canvas and head into the social realm. Is this a special homecoming for you?

Yes, it is. I did my first piece that was sprayed directly onto the existing architecture here, in Kunsthalle Bern, invited by curator Roman Kurzmeyer in 1998. I found out so many things when doing this piece – how a painting behaves in space and develops a new spatial agenda.

Exhibition view. Katharina Grosse. Studio Paintings, 1988–2022 / Photo: © Rolf Siegenthaler /

Kunstmuseum Bern

How much strength exertion does your work actually require? Back then, did it feel like you were entering a male-dominated realm? Was it empowering and Feminist-like?

The physical movement is certainly very impactful in my work, and yet so strongly connected to mental power. At the beginning, I did not fully realise how suppressing the patriarchal system was, and how powerfully it kept us in check. I ignored it in order to develop my work.

Exhibition view. Katharina Grosse. Studio Paintings, 1988–2022 / Photo: © Rolf Siegenthaler /

Kunstmuseum Bern

Why is the metaphysical mind not enough for you when perceiving your paintings? Why do you want to involve the body, with all of its ‘illusions’?

I understand illusion as a field of possibilities. There is no difference between reality and imagination. Painting gives me the possibility to grasp a small speck of the fleeting thoughts that travel through my mind. Therefore, painting is an open system. For me, it seems to develop in a mixture of movement and spatial relationships and then it materialises, coming from beyond and landing on a certain area – whether this is outdoors, or on a stretched canvas, or on materials that I have found in a given situation.

Exhibition view. Katharina Grosse. Studio Paintings, 1988–2022 / Photo: © Rolf Siegenthaler /

Kunstmuseum Bern

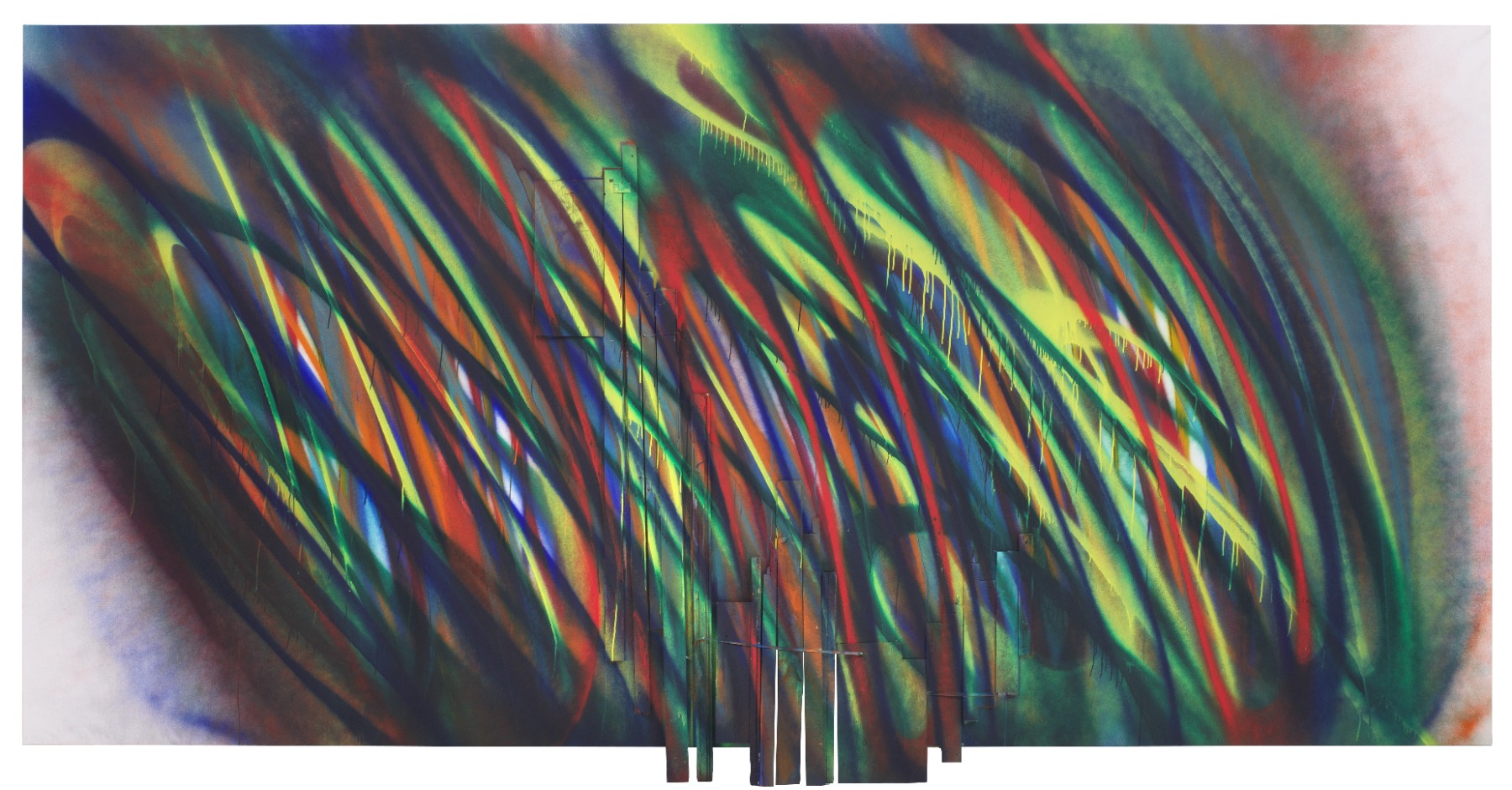

Katharina Grosse. Untitled, 2020. Acrylic on canvas and wood, 299 x 605 cm / Photo: Jens Ziehe / Courtesy: Galerie nächst. St. Stephan Rosemarie Schwarzwälder, Wien, Österreich / © 2023, ProLitteris, Zurich

The absence of a strict division in your work between architecture, design, sculpture, painting, performance, theatre and even engineering invites the idea of Gesamtkunstwerk. For example, your relatively recent show at Hamburger Bahnhof. Has this Wagnerian idea informed your total grasp of reality? Why do you find it relevant for your practice?

I do not look upon my work as a Gesamtkunstwerk. I think it follows the tradition of cave painting or fresco painting, shifting the painting into an incongruous relationship with architecture or a given situation.

I also find soccer really inspiring – how the players anticipate each other’s movements, how they divide the field and strategise together while playing and developing a plan, yet combining rehearsed practices and inventions on the pitch.

Exhibition view. Katharina Grosse. Studio Paintings, 1988–2022 / Photo: © Rolf Siegenthaler /

Kunstmuseum Bern

Katharina Grosse. Untitled, 2021. Acrylic on canvas and wood, 349 x 248 x 80 cm / Photo: Jens Ziehe / Courtesy: Gagosian / © 2023, ProLitteris, Zurich

You also build on the great tradition of German romanticism by taking the legacy of Gerhard Richter to the next level. Just like his mechanical abstract paintings, your (brush)stroke – expressive yet depersonalized, even mechanical – de-romanticized the painting. What are the questions you've been (and still are) dialoging with him?

I want to make my work as present as possible within our social fabric, and offer notions of alternative thinking.

Kant’s aesthetic equality (the judgment of taste which is subjective yet universal) is considered a founding principle of modern democracy. The phenomenological experience of your artwork also invites dynamic and equal vantage points and links with the socio-political imagination. How does this political dimension of your work formulate? Is this something critics attribute to your creations post factum, or is there a rather conscious intention at the outset?

Are we not about to turn our backs to the credos of modernism? I am not aware of what critics attribute to my work. Multiple vantage points are very influential for my process in my site-related works. They force me into areas that are almost translingual, meaning that I am encountering aspects that I don’t understand when trying to grasp them in my mother tongue.

Exhibition view. Katharina Grosse. Studio Paintings, 1988–2022 / Photo: © Rolf Siegenthaler /

Kunstmuseum Bern

The Bern show stresses colour as a founding principle of your practice: ‘Its physical presence, its sensory and political potential, and ability to embody movement.’ Why is your colour so bright and theatrical? Do we need theatre and illusion to see reality?

Painting has the ability to be very close to you. Like a sound or a voice, colour can catch hold of you. With my painting, I seek to compress emotions and cause vehement agitation. I want us to be so disturbed, positively or negatively, that we develop the wish to change something.

Exhibition view. Katharina Grosse. Studio Paintings, 1988–2022 / Photo: © Rolf Siegenthaler /

Kunstmuseum Bern

Your most recent work shown in Hong Kong seems to have lost the punk-like edginess of spray and stencil paintings, becoming almost like a post-human expression of AI. Is this reading of further detachment correct?

You could read it like that. I do not express anything, including AI. I am interested in actualising every present moment in the process of painting, again and again.

Exhibition view. Katharina Grosse. Studio Paintings, 1988–2022 / Photo: © Rolf Siegenthaler / Kunstmuseum Bern

Even if you encompass the whole air field or park in your artwork, you still consider it to be a painting. In your work, qualities internal to painting fuse with the external realm. Why is it important for you to call yourself a painter? You could have gone into installation art completely…

Labeling my work does not help me in the process. I see myself mainly as a painter because I like the non-linear time structure that painting is able to provide. Like no other medium, it is a time cluster – it has no beginning and no end; the past and present are reversible.

Katharina Grosse. Untitled, 1993. Oil on canvas, 130 x 170 cm / Photo: Sebastian Schobbert / © 2023, ProLitteris, Zurich

What is art’s role in times when reality is stronger than aesthetics – like in the case of the war in Ukraine?

I see the artist’s role as mainly providing alternatives for our thinking and for our decision-making. I also believe that we provide constellations that enable spiritual experiences. Art is demanding. Painting is an imposition.

Katharina Grosse, 2022. Photo: ©Aman Shakya/SCAD Savannah / College of Art and Design

You and your team are currently working on your new institution, the Wunderblock Foundation. Located in a Soviet-period farm near Berlin, it will showcase your work and will offer many more art-related activities. What is your vision for this place, and when can we visit?

The Wunderblock Foundation is a nonprofit organisation. The foundation’s goal is to support painting in its most adventurous forms. It strives to create a space for thought, practice and experimentation, within which the question of what painting can achieve within the social framework can be addressed in risk-taking ways. We are developing and recycling the old buildings – slowly, step-by-step – and hope to welcome you in the coming years.

Special thanks to Kathleen Buhler, Natalija Martinovic, Kristin Rieber and Charles Bromley.