Parade of Flying Episodes

A conversation between artist Beate Poikāne and curator Viktoria Weber about the exhibition Parade of Flying Episodes, hierarchies within performance art and the dream of flight as a desire to break free

The exhibition Parade of Flying Episodes opens on February 1st at Riga Art Space and within it the visual artist Beate Poikāne depicts the lustful, nocturnal experience in dream sequences with the support of sound artist and researcher Andrejs Poikāns. The performance Parade of Flying Episodes (2023), Beate’s master’s research in Scenography at the Art Academy of Latvia, was the starting point for this picturesque venture. Together with Andrejs and Laima Jaunzema, choreographer, and performer, Beate took inspiration from Gaston Bachelard’s essay Air and Dreams: An Essay on the Imagination of Movement (1943), mythological legends, science, art-historical discourses, but also personal dream experiences to show a series of flying episodes. In this exhibition context Beate extends the artistic research and translates the performative moment into space. The audience is guided through sequences of theatre situations that spotlight object-performers as active agents. A sky-like stage set, kinetic sculptures, video works and a sound installation seduce the audience into a twilight state between dreaming and waking. Hence the self-performing environment invites the audience to dream away within the liminality of fiction and reality.

Beate, a visual artist and scenographer, is currently pursuing a master’s degree in Performing Arts at Stockholm University of the Arts. She is an alumna of Scenography (MA) and Visual Communication (BA) at the Latvian Art Academy. Her artistic research manifests in various visual forms, mainly in theatre performance and installations that function as storytelling tools. Her artistic pursuits revolve around decentering the human performer and introducing non-human elements into the center of visual dramaturgy. Through the exploration of the impact of fictional narratives on perceptions of contemporary surroundings, Beate is investigating their influence on information interpretation and examining the dynamics between fictional worlds and our relationship with the physical realm.

For the following conversation Beate and Viktoria meet to discuss Beate’s approach to the dream of flight, inspirational myths and paintings, the role of object performers within the show as well as its possible function within Latvian society.

Beate Poikāne

Viktoria Weber: The topic of the dream of flight has been accompanying you for quite some time now. How did you first get in contact with the concept? I have been wondering if you first dreamt about flying and therefore got more interested in the theme and its connotations or if you first researched the dream of flight and then started to fly off in your dreams.

Beate Poikāne: It all happened in a funny way! I received this text [Gaston Bachelard, Air and Dreams: An Essay on the Imagination of Movement (1943)] from the poet Lauris Veips that had translated it into Latvian. As an expanded group of friends, we were all reading it collectively at a countryside house during the summer. It was like a summer camp for ourselves based around dreaming. So, every night we would go to sleep, try to dream something, write it down in the morning, followed by a discussion and that would be one of the main activities during this week. That was the time when I read Bachelard’s text. So, I was also in a very particular setting. When I approached this special artist, I knew he discussed the poetics of space. But I had never heard about the essay on Air and Dreams. At that point I preferred it much more to the dream interpretation by Freud that felt very stiff. I just liked how material art was approaching it in a very fluid and associative way. Later on, I had to work on my master’s project, and I needed to pick a text. I was very sure that I did not want to work with classical plays. I chose Bachelard’s essay because of the references he has chosen, how vivid they already are, like images in the text. I feel like the text itself gives so much visual imagery that is, for me as a visual artist, just very pleasant to read.

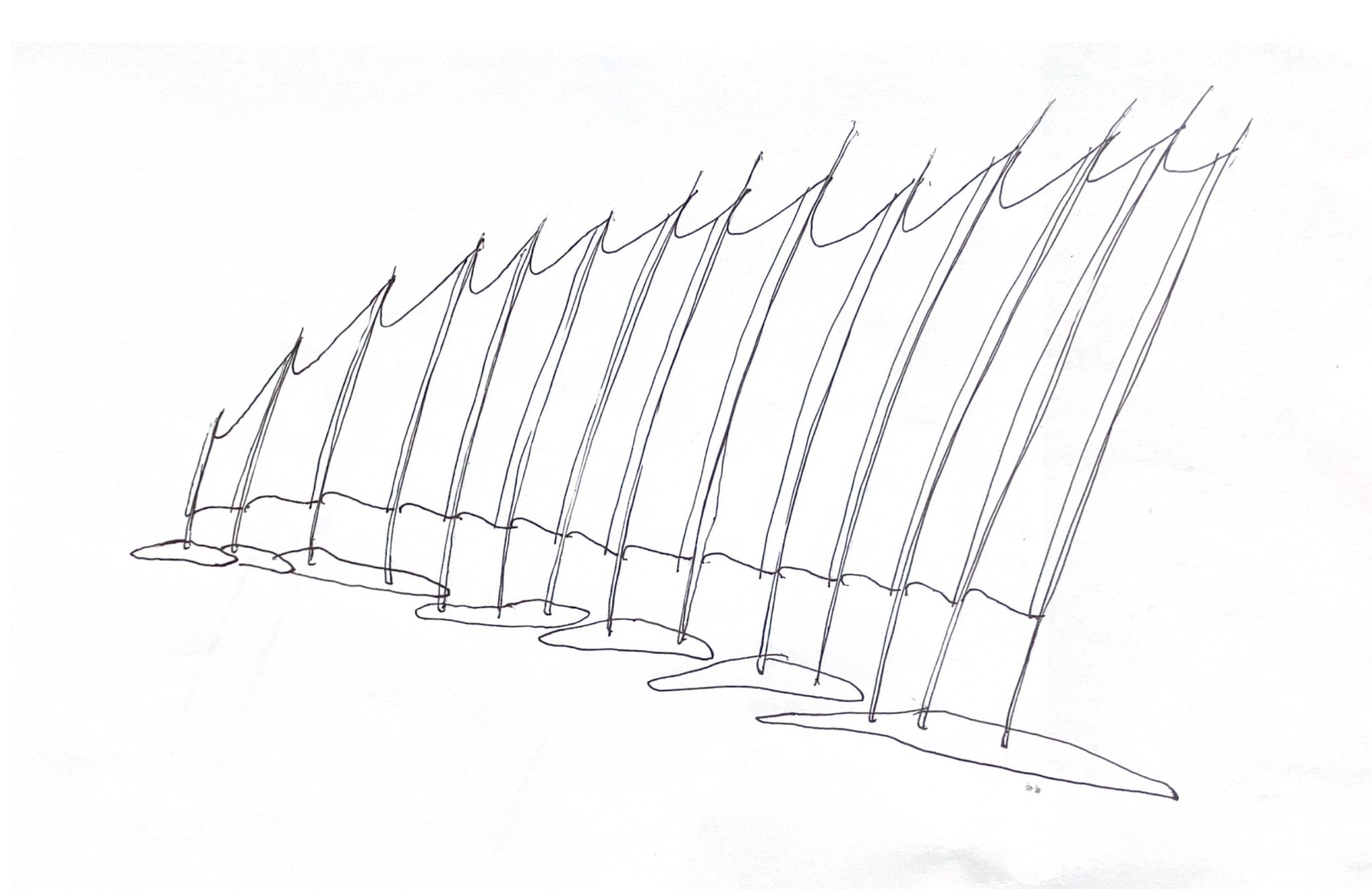

Sketch for the exhibition "Halycons", 2023

VW: In a way I feel like this exhibition is a good example for your practice in general. Knowing your background there are a lot of intersections within this exhibition project. It, for example, connects your background in performing arts with your knowledge in scenography because the space with its object-performers becomes a self-performing environment.

BP: Yes, I definitely think everything makes sense for me, ever since I got more involved into performing arts. I feel like I can combine all the ways of artistic expression that interest me and therefor my works become like collages. Before that I tried to work with one single kind of idea, but now I work in multiple layers, I mix different references, different mediums. A lot of approaches come from what I have learned now in this fine art setting or my studies because it taught me how to work with multiple sources or inputs. And I think I have gotten better at understanding how to compose this polyphony into a singular composition. This is much more interesting as then the story isn’t one sided but offers multiple perspectives on how to view a topic.

VW: It is very captivating to look at all these different facets of the dream of flight you found. I was quite amazed by this variety that also tries to widen a eurocentric or western vision of the dream of flight. For example, you also draw from the Flying African myth, that I have never even heard of before the research. Do you have a favorite inspiration between all these tales and stories?

BP: I think there are much more tales that I’m not even aware of. I was struggling so much to find all these tales. In the beginning, I was asking friends and acquaintances if they knew any kind of story about flying. I have a couple of favorites, but I relate to all of them in different ways. One myth comes to my mind now that’s not even in our collection. In Latvia we have this myth about flying lakes. It is about this huge body of water that flies around. It happens in ancient times before the land was finished. People will be walking around and when by accident you call the lake by its name, only then it falls down. I think that is really beautiful. This image of a huge body of flying water, in a way you can interpret it quite literally as rain, but in my imagination, it is really like this bubble of water. It’s interesting that this name tames you down. When something is named, it’s no longer an abstract because once you put it into language, it gets its shape. I think that’s quite an interesting myth from my own origin.

Of the other references the political paintings of Pieter Bruegel have been very influential for me. I really admire the composition that he has chosen [in Landscape with the Fall of Icarus (1560)]. I have been thinking how to work with this type of composing also in dramaturgy, or on stage. How can there be an action that takes a lot of attention, but it’s totally unimportant. And then the important thing maybe happens in the foreground or is somehow less noticeable. I love how he shows that often, we don’t even know what is the most tragic or the most important kind of discovery.

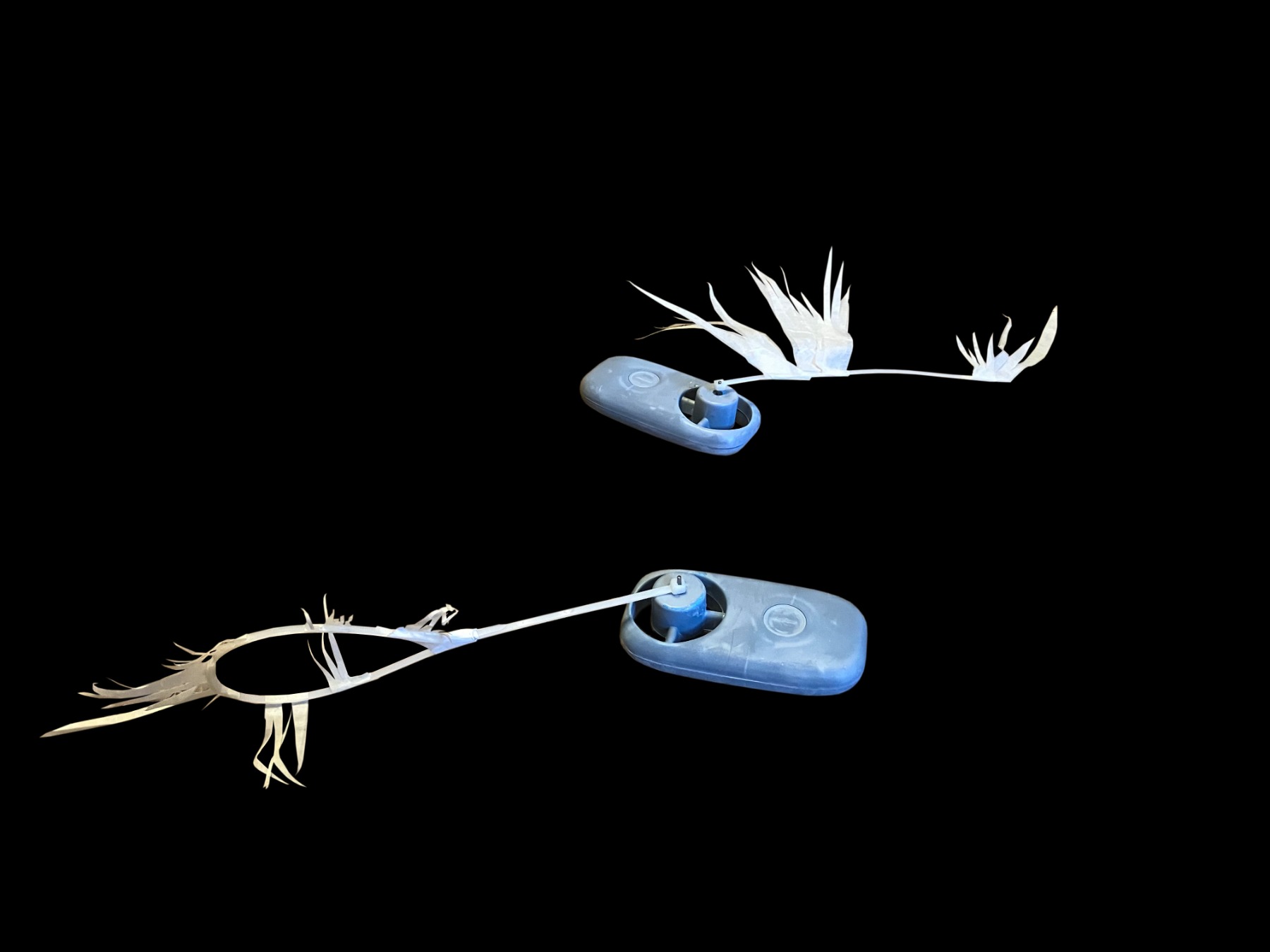

Kinetic sculptures from the performance "Parade of Flying Episodes", 2023

VW: What is also very interesting about both these examples is that we kept mentioning water. In Bruegel’s painting a huge part of the canvas is filled with the water Icarus falls into, then there’s the flying lakes you mentioned, it feels like a lot of these tales have this component of water. Water and air both have a very poetic nature that invites people to dream away. What you said about the dramaturgy of Bruegel’s painting is also interesting, because you also play with hierarchies when you introduce object-performers into your work. How did you come to this approach? How did the idea to work with non-human performers develop?

BP: Entering the scenography department, I understood what kind of power objects already had. We would usually develop our own interpretation of a text. Then I would see how much I can already reveal by selecting objects or writing them out of the text. I see how they tell a story by themselves that I would often feel like a visual semiotic already reveals the plot. Currently I am focusing on reconfiguring human – object hierarchies on stage, so they become more horizontal. I was always interested in contemporary performance, but I never found a way how I could participate, because I’m not feeling so much like a performer myself. I am not particularly into acting, singing, or dancing. I didn’t want to be on stage in that format, but I found it interesting on how we can convey messages in this form. Then I gradually understood how my objects can work as storytellers, or like video can work as a storyteller, and this can create an atmosphere. It’s just a different way of storytelling, basically.

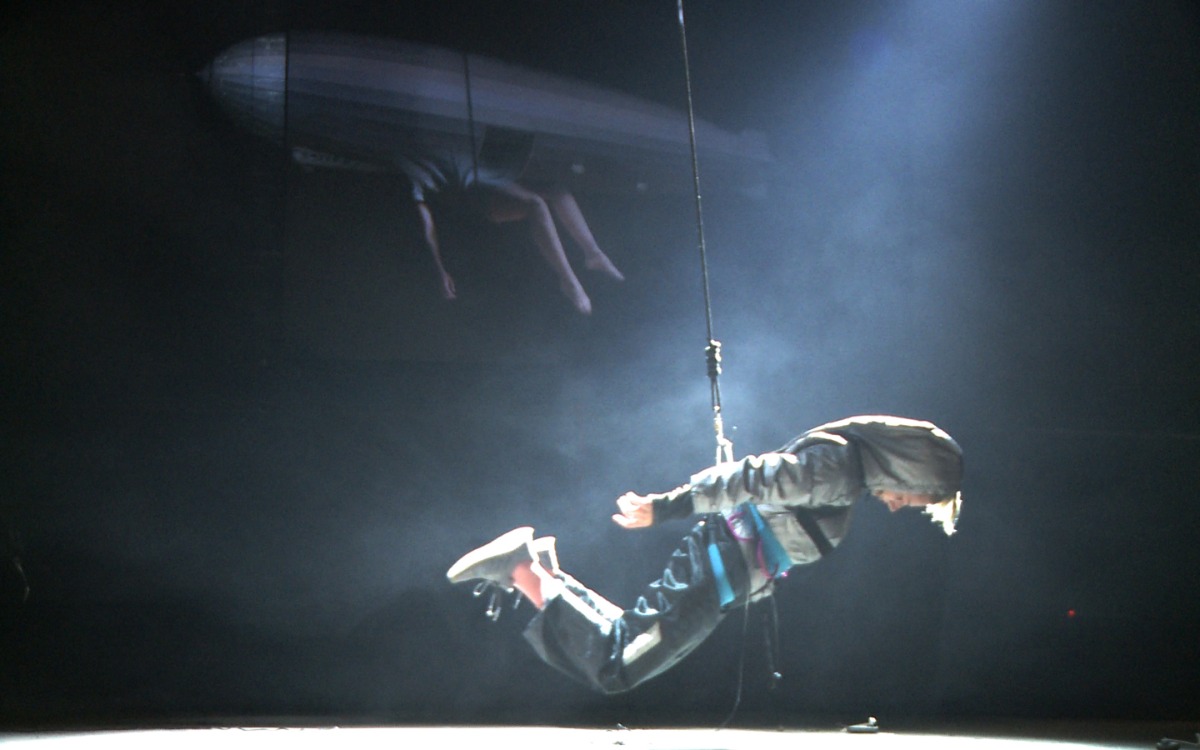

From the performance "Parade of Flying Episodes", 2023. Scene 3, Tu jau zini kur concert hall

VW: I also feel like there’s a correlation between how you work and the topics you work on. You create this atmosphere that tells stories of imagination, fiction, reality and dreaming.

BP: During the process of creating the performance Parade of the Flying Episodes (2023) I understood how much attention you can give to an object by leaving the stage. By leaving the stage, one gives this spotlight to the object. When I do perform with objects, it’s often like my body has a different function. I often feel like I’m there as a holder, or as a stagehand. I’m just supporting the object and I want to show how beautifully it moves. It’s about changing the roles.

VW: How do you feel about working on this exhibition? For the longest time now we both have been working on it mainly online from abroad. How do you feel about this working process?

BP: I’m grateful for the opportunity to rethink the performance and understand how it could function as an individual artwork without anyone, like actively changing it. So, this is very good because the performance was created quite fast. Now I had time to reflect upon it for another half a year. And it feels like I’m getting closer to a conclusion. It was a smooth and comforting experience to speak out my thoughts, discuss them with you and put them in a more organised sequence by doing so. It also has been interesting in terms of thinking about space, because I have this room in my mind where I try to imagine the sculptures, the observer, and so on. When I came to Riga again, I realized how different the space was. Each time I exit the room, I feel like this imaginary space, it’s so different than the physical space. I have always been interested in this relation and now I must understand how to build this relation into the actual space. When I wasn’t in Latvia I was mainly working on sketches, the layout plan and concept.

VW: There is always a discrepancy between a space and the idea of a space. To portray that is quite interesting.

BP: I have this physical space in these physical objects, but they are signifiers for other stories, and I know that they also contain other kind of fictional spaces at the same time. So, this mental physical space exists in parallel.

Sketch for the exhibition "Fish fin wall", 2023

VW: What you mentioned earlier was that you’re working with the topic more intensely now, you are rethinking the performance, and you start concluding. What is the conclusion of this whole process?

BP: I don’t know the answer yet because it’s not the end. I have been in a relationship with this work for so long. I will see when it is finished fully in the space if it resolves itself. I hope this exhibition will mean something for the Latvian context as many of the myths that I took as a starting point, are the ones that were embedded into Bachelard’s essay and are from Central Europe. Latvia is a very different cultural context. I want to see how the audience from Riga relates to it. I am also trying to answer this question for myself: Why is it important for me to think about the dream of flight in this particular city? Reading certain myths about flying, makes me conclude that it’s often a fictional solution of a problem. And I think in a way, I’m looking for a solution in this place where I see so much roughness in my surroundings. I think and don’t know how to make the real circumstances softer for the people, and then I start to think of dreams, and daydreams that allow to transcend any kind of difficulty by offering a moment of rest for the mind. I see a bit of a problem here with escapism, but I wonder of fantasy and images as active tools for affecting reality and imagination of the future. I think of Ursula Le Guin here, who was talking about fiction as a very powerful tool for reshaping the world that we see.

VW: If you look at all the different tales, then even though they’re different, and they come from different places, they are united by their longing for freedom, by this desire to break free. It can be an enriching exchange to take inspiration from a variety of tales around the dream of flight and then put it in this very specific context.

BP: When thinking about dreams, all of this shows that you can always a have a certain amount of freedom in whatever circumstances you are in - in your mind. Maybe that’s the rosy part about it.

Title image: From the performance “Parade of Flying Episodes” (2023) scene 3, Tu jau zini kur concert hall. Performer Laima Jaunzema