What’s in the box?

Curator Romuald Demidenko talks to Līga Spunde on the occasion of her first solo exhibition in Lithuania

During our conversation, just a few hours before the opening of Līga Spunde’s exhibition Surprise, Surprise at apiece Gallery in Vilnius, we took a moment to reflect on our past collaborations – the first of which was in an informal setting at the group show Meet Me at the Metro Station, hosted in a private apartment in Amsterdam. At my invitation, Līga arrived with a cuboid plaster sculpture painted in Tiffany blue. Later that same year, I wrote a paragraph-long text for her cooking performance at the Komplot art space in Brussels. And later, we met up in Riga, to plan the Vilnius project and ponder what our potential liaison in the neighbouring capital would entail for both of us.

Līga Spunde, studio selfie at the ISCP residency, New York City, 2023. Courtesy of the artist

Romuald Demidenko: Your installation entitled Surprise, Surprise is your debut show in Lithuania. It’s a site-specific work whose idea arose around the location, the glass-box space of the apiece Gallery in the Naujamiestis area of Vilnius. It also draws connections to our previous collaborations and your fascination with a particular event: in January 2017, Melania Trump presented Michelle Obama with a large blue Tiffany & Co. package, its contents undisclosed. Looking at current global political developments, there’s a renewed focus on the upcoming US elections. I’m curious, what initially sparked your interest in this topic, and how do you see it from your current perspective?

Līga Spunde: Back then – seven years ago, when we both met in Brussels during the US election – it was a big shock for everyone – the fact that Trump had been elected. And at least I had this feeling that people in Europe were completely disappointed; even though there were ideas about what to expect, no one really knew what exactly that would mean for global politics. And obviously, what occurred at that time had a huge impact on the world in general. I found it kind of hilarious that soon after Donald Trump was elected, he and Melania made an official visit to the White House to meet the Obamas, and there was this clumsy moment that was captured on video. It was super popular online because people were wondering what was inside ‘the blue box’. I found it both quite funny and symbolic that there was this blue box and so much speculation about it. In a sense, it referred to the whole situation in general.

This year is different, and obviously these elections in the United States play an even bigger role, especially for our region – not only the Baltic States but for this part of Europe and all our neighbouring countries. Specifically because of what is occurring in Ukraine and because of what Trump has said in recent interviews about NATO and Putin. I think it’s quite tricky. So, there could be another gift-wrapped box coming. I mean, I hope not, but quite possibly we will need to face this and, alas, there is not much we can do about it. Moreover, with the situation in Palestine and the Gaza war, things are only becoming more intricate. Of course, [the USA] being geographically distant and not directly linked with Russia, probably gives [most Americans] the idea that it’s not worth investing more money and aid into this region and so forth. It’s just very concerning, because it could make a big difference.

And what do you think Surprise, Surprise addresses in the local context of the showcase-style gallery in Vilnius? What significance does it hold for you? What do you believe it would symbolise, and how would you like this work to be received by the local community?

I knew that apiece Gallery is a unique space, including the idea and shape of it, and the fact that it’s a glass showcase that is open 24/7. So, from the beginning, I was thinking a lot about what I would like to give to the locals. It’s always a bit tricky, as you never know if what you’re giving someone will eventually be appreciated or not. Then I thought of asking my Lithuanian friends what are the things that they would bring when going abroad – but as Latvians and Lithuanians are pretty similar, it was really hard to find something really special. Also, I hadn’t had a chance to do a solo show in Vilnius yet, which is referenced in the title of my installation. As I live in Riga, which is about a four-hour drive from Vilnius, I came here with the best intentions of showing something personal and intriguing, and considered it both an artwork and an offering. Actually, besides our previous history with the Tiffany’s blue box project in Amsterdam, my main intention was to bring something palpable as a friendly, neighbourly gesture. You mentioned in your text that a gift is really never ‘for free’, and has to be reciprocated in one way or another; this is true.

You bind digital techniques with dark-ish symbolism and humour, blending your own stories with more universal truths – and also stereotypes. What stories did you think of conveying through your work?

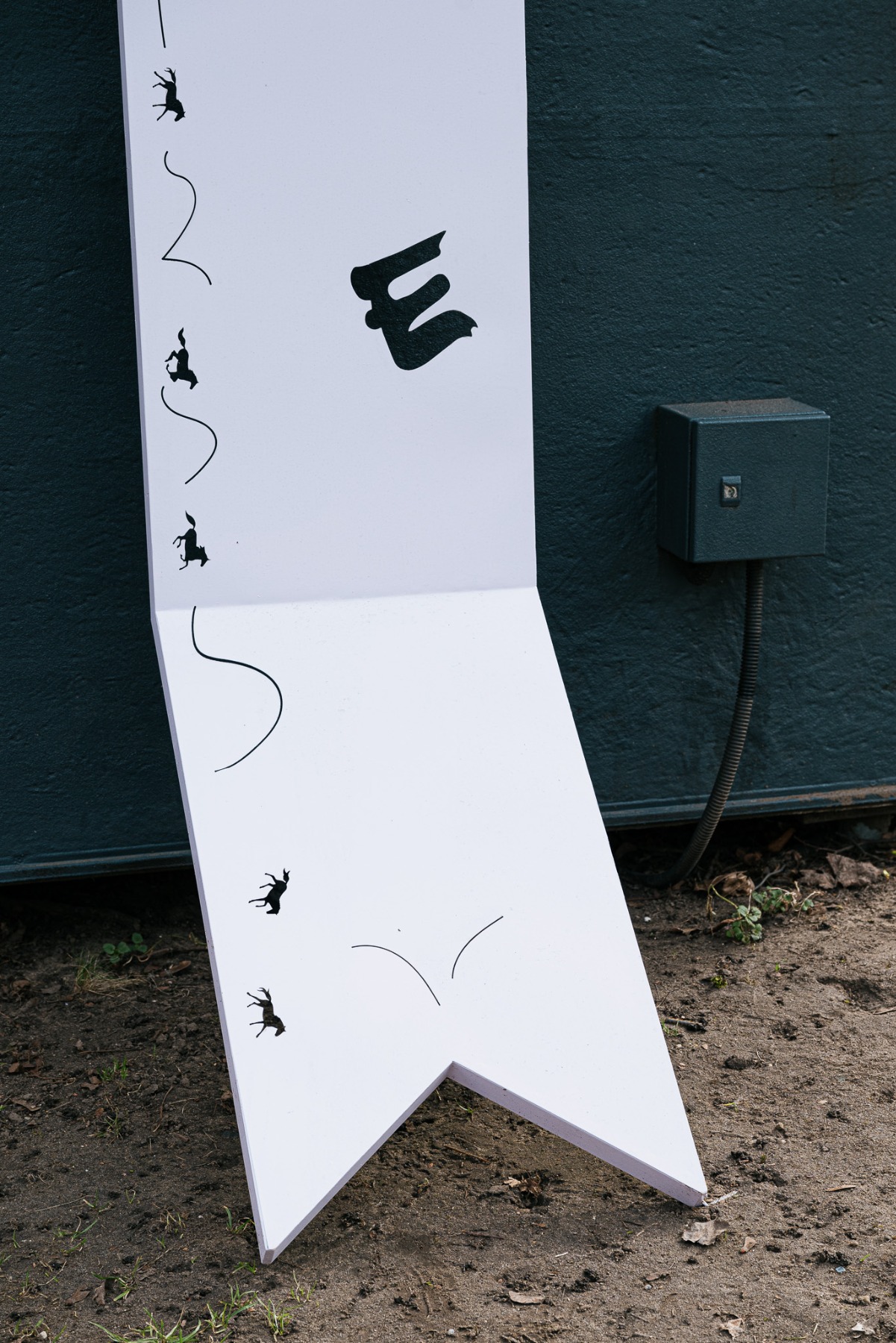

I’m always trying to use humour in my work (laughs). There are these motifs that I associated with myself if I were to bring a gift to an imaginary Lithuanian friend. They were laser-printed in the ribbon made of steel, and connected with the bow sitting upon the roof of apiece Gallery; one of them is šakotis, for example. To me, it’s very Lithuanian, and I know you have something like this in Poland called sękacz, but we don’t have anything similar in Latvia, so I would rather take it home for myself than think of anything else I could bring from Riga (laughs). You know, it’s something between a traditional sweet or bread, or a souvenir. But then I stopped thinking about the gift itself that much, and I focused more on the gesture – something that could be referred to as ‘good intentions’. I can only hope that the Lithuanian audience will appreciate the gift, or at least the intention.

You’ve also decided to incorporate laser-cut silhouettes of horses. What do they represent?

It refers to a specific joke that apparently Lithuanians have about Latvians – a slightly derogatory expression that Lithuanians use to call Latvians, namely, zirga galva (Latvian)/žirgo galvomis (Lithuanian), which literally translates as ‘horse head’; as far as I know, Latvians assume that this is how Lithuanians call them. I think we are very close to each other, and we support one another at specific important moments, but at the same time, of course, our relationship is also a bit competitive, and we’ve always had jokes about each other and sometimes still do make playful fun of each other. But apparently, zirga galva doesn’t mean anything bad. So I thought about playing around with this a bit, but when producing the metallic sculpture, I realised that it could just as well be about ‘working like a horse’ – dutifully doing a hard job, but also in the sense of bringing the gift to Vilnius ‘with horsepower’. So I used some of the above-mentioned motifs as associations. You can also see in the piece a few ‘surprised eyes’ – an expression that is more about comic style. That was my improvisation about this ‘act of giving’, or the idea of a gift, and putting it into an action.

There will be more of your work on view in Vilnius, but this time as part of a group exhibition at the MO Museum. What are you going to present there?

I will take part in a group show focused on the art scene in the Baltic states. I will be showing A Panic Attack on a Sunny Day, a project which was presented for the first time in Valencia in 2023. It’s composed of lenticular prints with stands depicting facial expressions of fear, and sculptures of oranges with more grumpy faces. When making this work, I was very focused on the idea of how I should represent the point of view of someone coming from a different region, as there’s always this difference between the eastern and western parts of Europe, and it also referenced what was happening in Ukraine at that moment. My idea was to bring a work that depicted expressions of fear and of confusion – of not knowing what will happen. It was also inspired by a blog written by a friend of mine who actually moved from Latvia to Spain when the full-scale invasion on Ukraine began because she freaked out and wanted to find a safe place for her family. I knew this girl from when we were teenagers, and when I found her blog, I thought of it as something to refer to; much the same way as she was continuously referring to the Ukraine situation every day, despite being in a sunny place and quite a bit farther away. The idea behind the work was to show that the emotions and facial expressions on the lenticular prints could be scaled down to the oranges – to bring awareness and a reminder that it’s still happening [the fear and confusion in Ukraine and beyond].

You emphasise that personal narratives and universal truths play a major role in your work. On the other hand, Byung-Chul Han argues that we are also witnessing a narration crisis due to the pervasive use of digital media in our lives. How do you look at this?

It’s a good question, but I don’t think we’re witnessing the end of storytelling. As I use this digital environment to find stories to work with, I must say it’s like an endless opportunity to read about so many things, so many odd and strange things I never would have known about without the internet. Maybe the problem has more to do with the fact that there are too many stories out there, and that makes it impossible to navigate through them all. I mean, that’s the internet’s number one problem – there’s too much information and it’s hard to divide and sort it all, but on the other hand, there are countless great stories to be found online. But as for me, stories do play a crucial part in my work. In my early projects, it seemed to be all about personal stories, but then I began to blend them with found stories or others that I could relate with. I agree that people are increasingly using images to communicate. It also resonates with how nowadays people use alternative and brief ways of communicating and expressing themselves by sending each other GIFs or memes; probably most of us do that. I think there are many layers embedded in this new image-based culture – personal meanings, inside jokes, and so on. I find it actually very interesting that we’re using images to this extent, especially representations of emotions expressed by others because they somehow show even more precisely how we feel.

It’s hard to think of anyone else using graphics the way you do. I’m curious – is there something from your upbringing in Riga that might have served as inspiration for your work later on?

The symbols and characters I incorporate into my work often stem from my childhood experiences, particularly from cartoons. Growing up, I remember watching Disney movies and other related content. I would say that the characters I use in my work reflect rather western, pop-culture influences but also modern Latvian culture. There are also inside jokes embedded in my works, often found in the details of the drawings. I enjoy incorporating local fashion brands and other subtle references. Overall, I believe this blending of influences is a result of globalisation. The younger generation in particular is heavily influenced by global trends, blurring the lines between what is considered Latvian and what is not. Regarding colours, they are highly specific to me, and not necessarily typical of the Latvian aesthetic. In Latvia, the most common colour associated with Latvians is grey. We even joke about having ‘more than 50 shades of grey’ (laughs). Being part of the first generation after Latvia regained independence in 1990, I was influenced more by western culture during that time of transition rather than by anything produced specifically in Latvia.

Back in 2021, during my visit to your studio in Riga, I noticed a shift in your work towards a more sculptural direction. And it appears that recently you’ve been embracing space more freely, and that your work is growing in size.

I’m curious about pushing the boundaries of digital mediums and aesthetics, and exploring how they can translate into physical materials, which is why I’m planning to experiment more with things like 3D printing and probably CNC cutting. While digital drawings may have taken a backseat for a while, they certainly won’t disappear from my practice. So, yes, I’m a bit focused on manifesting my ideas into more physical forms.

You’re based in Latvia, yet your work has garnered significant visibility on a broader scale in recent years: from completing your ISCP residency in NYC to preparing for the next one in South Korea. How would you say your perspective has shifted towards different scenes, including the one in the Baltic states?

I’m very excited about being selected for a MMCA residency in Seoul, and will spend two summer months there. I’m really looking forward to it. I think I have been very lucky to be active as an artist and to stay active. Back when we met in Belgium, I had been pursuing my education at the Art Academy of Latvia; it was shortly after my graduation and I had such big ideas and illusions about everything. But then you have to think a bit more realistically about how to make a living and, unfortunately, in our region (but not only), it’s still not really possible to make a living by just making art. Seeing a bit more art somewhere else makes me realise that artists are more or less facing the same issues everywhere. So I know it’s a joy, but it’s also a struggle. I feel that throughout these years, I have found my way of keeping a balance – to be able to work on projects that interest me, and even try out bigger things or do more because I have always been interested in developing my ideas, investing a lot, and trying out new technologies. I guess I’m quite adventurous about this whole journey. And I have received regular support from the Latvian Culture Capital Foundation. My residency in New York City was made possible thanks to the prize from the Kim? Contemporary Art Centre. It was amazing to visit such a dynamic place that actually gives you so many ideas and so much inspiration; I had this feeling that I want to try out so many things, and it was great to just see the scene. But, of course, it’s not that easy to be there, and I think we all are aware of that. It’s also a different scale for opportunities because I had this feeling that if one door is closed, you can still knock on another door – and there are just so many doors to knock on out there.

I’m lucky to be working with the Kogo Gallery in Tartu. I have a feeling that, in general, each of the Baltic countries seems more focused on being friends with a bit more geographically distant countries, kind of forgetting that they actually have great friends right next door; it's something that we are not appreciating enough. But I see that this is gradually changing, and that there are organisations whose programming shows a more open approach to collaboration. That’s why I also believe that the gesture of bringing a gift when you visit your neighbour still makes sense.

The exhibition is on view until May 5

Romuald Demidenko is a curator based in Warsaw.