Sami artist pioneer at the National Museum of Norway

Ekaterina Sharova

An interview with Sámi artist Britta Marakatt-Labba

Despite their extensive activity since the 1980s, critical Sámi artists have until recently been overlooked by art institutions in the Nordic capitals. The current polycrisis presses one to question the established relations between art, industry, knowledge production and nature. Artists can act as epistemological agents challenging hegemonic power structures, including mainstream academia as an agent of knowledge-power construct in a society. The embodied experience of living in an indigenous community challenges the Western epistemology and offers a shared, polyphonic knowledge ecosystem as an alternative. Can indigenous artists show ways to organize power toward balance and harmony, or offer counter-histories of sustainability?

Britta Marakatt-Labba is one of Sápmi’s most renowned artists. For more than half a century, she has created her stories with needle and thread. Embroidery and weaving have historically been dismissed as “women work”, but recent exhibitions as, for example, The Fabric of Democracy: Propaganda Textiles from the French Revolution to Brexit at the Fashion Textile Museum in London and the current Exhibition / Unravel: The Power and Politics of Textiles in Art at the Barbican Centre and many others show the enormous critical potential where artists turn traditional crafts tools into instruments of resistance.

Being born in Northern Sweden, Britta Marakatt-Labba moved as a child with her reindeer herding family between the Norwegian and Swedish parts of Sápmi. Together with Synnøve Persen, Aage Gaup and several young artists, she helped to establish the Masi Artist Group (Mázejoavku) in 1978 and the first Sámi Artist Union a year later, in 1979. This spring, her solo exhibition Moving the needle , which is the largest up to date, opened at the National Museum of Norway in Oslo (15 March–25 August, 2024). For the first time, you can see her early sketches and drawings, as well as iconic works such as Garjját / The Crows (1981), and Girddi noaiddit / Flying Shamans (1986). At the center of the exhibition is the monumental work Historjá, a 24-meter-long embroidery depicting scenes from Sami history, mythology, and everyday life.

In one of your interviews, you talk about your teacher Eline who inspired you to create art. Could you tell more about how you started as an artist?

There were many people who inspired me to start with art. My siblings were a great inspiration, we sat around the kitchen table and drew as children. I grew up in an environment where several relatives did duodji and one of my eldest sisters did embroidery. We were ten girls from the beginning, two of them died at a young age, and I had two brothers. We were allowed to experiment. We made sculptures using various materials found in nature. We didn’t have material we could buy, but used the material we already had, we had to look for ourselves. In the árran - hearth in the lavvu - we could find coal, for example, and draw with it. My siblings came home early in the year, since Sámi children from reindeer herding families were to move to the Norwegian side. They brought pens and crayons from school with them.

Art weaver Doris Wiklund from Kiruna, who passed away recently, was my weaving teacher. When I started at a preparatory art school, Roland Larsson was my great inspiration. When I came to Gothenburg to study, I was inspired by Elsa Agélii and her embroideries.

You helped to establish Mázejoavku (the Masi artist group) that gained great importance for the visibility of Sámi art and was the forerunner of the Sámi Artists’ Association. Could you tell more about your role here?

It started in 1979. Most of us graduated in 1978 at various art colleges. I was in Gothenburg, Synnøve Persen was here in Oslo and Aage was in Trondheim (Aage Gaup - E.S.). I often came to Oslo from Gothenburg and met Synnøve and we had discussions about moving back to Sápmi and starting an artist group after finishing our education. This would later be the Masi group. We started the Nordic Sámi Artists’ Association, which had a purpose to bring together as many artists, duojarat, photographers as possible.

How did you get to know each other?

Most of them were from Norwegian Sápmi. Sápmi is not that big. Synnøve studied here in Oslo, and I came often by train from Gothenburg and met them. It was very nice. It was important to have a conversation about how we should organize ourselves in order to create an artists’ union. We worked a lot with traveling exhibitions both here and internationally that went to the USA and Germany. We worked a lot non-profit at that time. There was no money. John Gustavsen, myself, Synnøve Persen and Nils Aslak Valkeapää - we had to take a tour of all the ministries - Sweden, Norway, Finland, in the Nordic Council in Copenhagen.

In Sweden it was very slow, very slow. Suddenly everything changed when Sweden joined the EU in the mid-1990s. Then they had to raise indigenous issues.

That’s interesting. I graduated as an art historian at the University of Oslo in 2012, there was no information about Sámi art in the curriculum at all. I learnt about it later working in the North.

It’s strange, and it’s after we all have been working for so long. Only after Documenta and the Venice Biennale, after Katya Garcia-Anton came to OCA , something finally happened. She has worked very hard to improve the situation. Another thing is that embroidery became more accepted as an art form. It’s not that easy. You have to have a lot of patience when working with embroidery.

There is a professor from the University of Oslo who taught about the canonical Oslo-based artist Christian Krohg. I met him at a seminar organized in connection with the exhibition Girjegumpi by Joar Nango and asked why Sámi art has not been a part of the curriculum. His answer was that "They are working on it at the Tromsø University". Has the situation been the same in Sweden?

Yes, but it’s not just Tromsø, it’s supposed to be all over the country. In Stockholm there was also little knowledge of Sámi art, but I actually have had solo exhibitions in Stockholm, Malmö and Gothenburg, and in Finland as well.

But now there is a change…

Yes, and this exhibition will go on to Kiruna and to the Moderna Museet, so that’s very nice.

Britta Marakatt-Labba «Historjá», 2007 (detail). Photo: Ina Wesenberg / National Museum of Norway

The work Historjá plays a central role in your artistry. I saw it at the University of Tromsø. How did you work with it?

KORO commissioned the work. Then I thought - it is our area Sápmi, Troms. What do the students passing by need to see there? Yes, Sámi history. It is very important, and not just for northern Norway or northern Sweden, but for the whole country. I started making sketches with different episodes about different historical events. I started with a forest of birch trunks, between which you could see faces peering forward. What do they want to tell those who see Historjá? They are the ones who passed away before us, the wise women. I think a lot about mythology when I work. We have three goddesses, Sarahkka, Juoksáhkká and Uksáhkká, the door goddess, the fertility goddess and the hunting goddess. Animals also come out into the forest, the ones we have in the Arctic areas, and lots of people go skiing. Then there are hunters who are able to tame the reindeer, and from it you can get materials for duodji. They learn how to move with reindeer. When people move from mountains and forest areas to the coast, they discover other Sámi, Sea Sámi, who also do agriculture.

Britta Marakatt-Labba “Historjá”, 2007 (detail). Photo: Ina Wesenberg / National Museum of Norway

We came into contact with Sea Sámi in the Troms area. It was so difficult for me when we met Sea Sámi, we had never read about our own history. I asked my mother, "Why do they know the Sámi language?" The answer I got from her was "They are verbally gifted". We do not own our history. If she had read about her history, she would have said that they were Sea Sámi who work with something else than reindeer herding.

So here you see reindeer herding, Sea Sámi, fishing, agriculture… What else was in Sámi history? Well, it was the Kautokeino rebellion. Sámi were angry at the authorities and they moved towards Kautokeino. In reality they burned down the trading booth, but in Historjá I burned down the church - because of everything the church has done to the Sámi population. They were subdued, they were not allowed to wear certain clothes and garments, silver was forbidden, everything was forbidden. Joiking was forbidden. Even in my days, the greatest sin in the world was to joik. People joiked when no one heard them, as for example my mother did without knowing I was listening. Just think that people don't dare to joik. Absolutely absurd.

Britta Marakatt-Labba “Historjá”, 2007 (detail). Photo: Ina Wesenberg / National Museum of Norway

So, people started joiking again?

I talked a lot with Nils-Aslak Valkeapää about the anxiety he felt when he joiked. He lived in Karesuando, and several people in that little place thought he was a sinner. It was very hard for him to resist, but he was one of those who started to allow joik and talk about joik as our way of expressing ourselves. It’s scary to be the one who goes ahead, but you pave a way, a path for others who come after. It was the same to start with visual arts. Duodji was well established, but Sámi art was not in the same way. It was more the art you carry around with you, in the form of pictures on knives.

One of the central events you chose for Historja was the Kautokeino Rebellion. The work was made almost at the same time as Nils Gaup’s film . Did you collaborate?

His film was made next to our summer location Skjold, at the FilmCamp in Øverbygd, but we have not collaborated directly.

Exhibition view of “Historjá”. Photo: Ina Wesenberg / National Museum of Norway

In a video for Historja, you hear a joik. Did it belong to your father?

It took a long time to find out that my father had a joik. There was a man in Övre Soppero who said: Now I will joik your father’s joik. That was 25 - 30 years ago. I had a relative who had words for the joik. My father got it from someone, but I haven’t found the man who made that joik. It would have been interesting to know.

What is it about?

He was good at raising dogs. So you joik about the man’s dog and about him himself, who was hardworking and very clever. He could work around the clock for days without getting tired.

When I was working on Historja, I thought that in a picture I want to tell the story in the same circular way as in the joik. You can read the picture from the left or the right, because everything goes around. The Sámi history starts from the left: the starry sky, mythology, sagas and tales.

You don’t learn that in a day. I didn’t read about Sámi mythology, I got that from my childhood. My mother was very good at telling stories, I learned from her.

So you had several female role models? What female images from Sámi history are important for you?

I have a lot of respect for ládjogahpir, the horned hat. I started studying it in the early seventies, because I was so fascinated by the very shape of it. I have a lot of respect for it, I don’t know if I would wear it.

When Christianity came to Sápmi, the ládjogahpir was banned. It was devilish. You couldn’t walk around with this hat. On the other hand, the East Sámi, Sámi in Kola peninsula and in the Kiruna area still wear it. You see a small hint of horn. But when I look at the old hat from the Kautokeino area, there are many horns at the back side. So that the clergy or the authorities would not see that they were still wearing their hats, they turned the horn over. It was still like this in the sixties and seventies.

Today, more and more people are starting to use it. It is about pride, it is a woman who has power. That’s how I look at it. They had horns on because they thought it was very powerful.

This exhibition is the largest to date - embroidery, graphics, sculpture, scenography... Could you tell more about the selection of works?

I have worked with church textiles. Someone asks - you work with church textiles, but you burn the church. But I think that a large part of Sámi go to church. I actually embroider a lot that maybe others don’t. Instead of having twelve male disciples, I put twelve women. I have a lot of that aspect in my church textiles.

Photo: Ina Wesenberg / National Museum of Norway

As for sculptures, I walked around with an idea in my mind for over 10 years. It was a bit like going and longing for food that you haven’t had the chance to taste. I casted some bronze sculptures, and I calmed down. I was satisfied, even though it has been over 10 years since I got the idea.

Photo: Ina Wesenberg / National Museum of Norway

There is also theater design. I have worked with both Beaivváš in Kautokeino and Sámi Giron Teáhter in Kiruna and at some films where I have worked with costumes. For Beaivváš I have also done scenography. Now I am in the process of decorating the new Beaivváš theater that is opening soon. I have a textile for the portal inside the theater. Then I also take up theater history, since it is also a secondary school, I also pick up what has happened in Kautokeino historically.

What do you like best?

Embroidery is my thing. I also work with such abstract things as church textiles.

Sometimes I want to rest from pictures and then it feels very nice to work abstractly.

Photo: Annar Bjørgli /National Museum of Norway

For the exhibition, you have created a commissioned piece, Luođđat/Traces, in which you warn against the consequences of the industrialization of society, as we see it in Fosen and in Kiruna/Giron. Fosen campaigners protested against windfarms on reindeer pastures recently. Why is it important to you?

This matter is very central. The young people demonstrated in front of the government building and the Ministry of the Environment and tried to defend the land area and Fosen.

I made embroidery. First we take the great cosmos which would be much better if we, humans, did not destroy everything. Humans want more and more, we are never satisfied. People move quickly and destroy large areas of reindeer husbandry, take land for wind farms or dig more and more ore. People are constantly looking for new minerals. For me, it is important to get this across in Luođđat/Traces. When you drill and dig, you get these deep marks. Everything is very fragile, and eventually the whole system collapses.

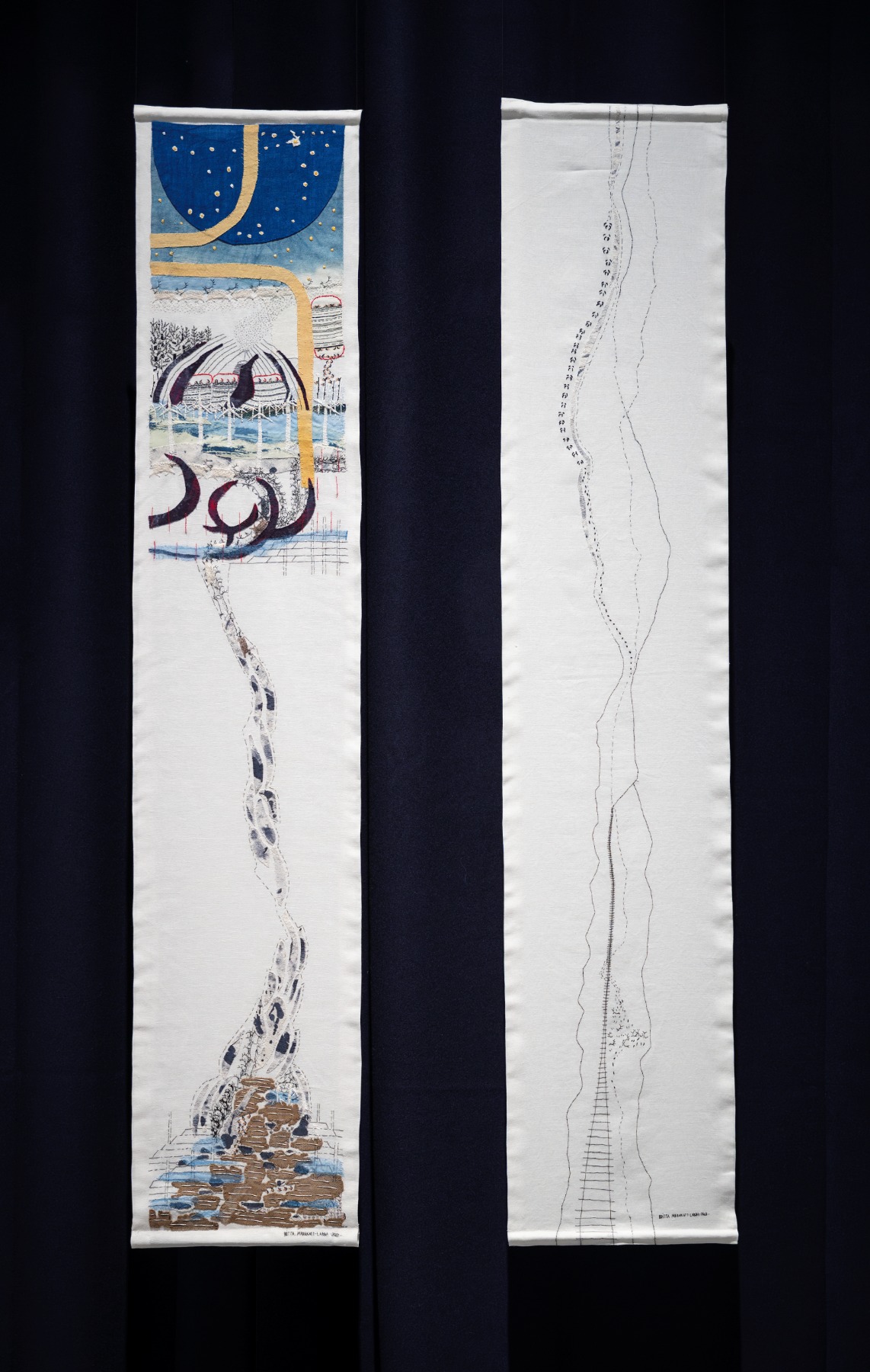

Britta Marakatt-Labba, “ Traces I and II”. Photo: Ina Wesenberg / National Museum of Norway

In Traces II I show the railway and the train tracks going down. The ore found in Kiruna must be transported, it is loaded there and driven to Narvik. In addition, there are also wind farms there that threaten reindeer herding.

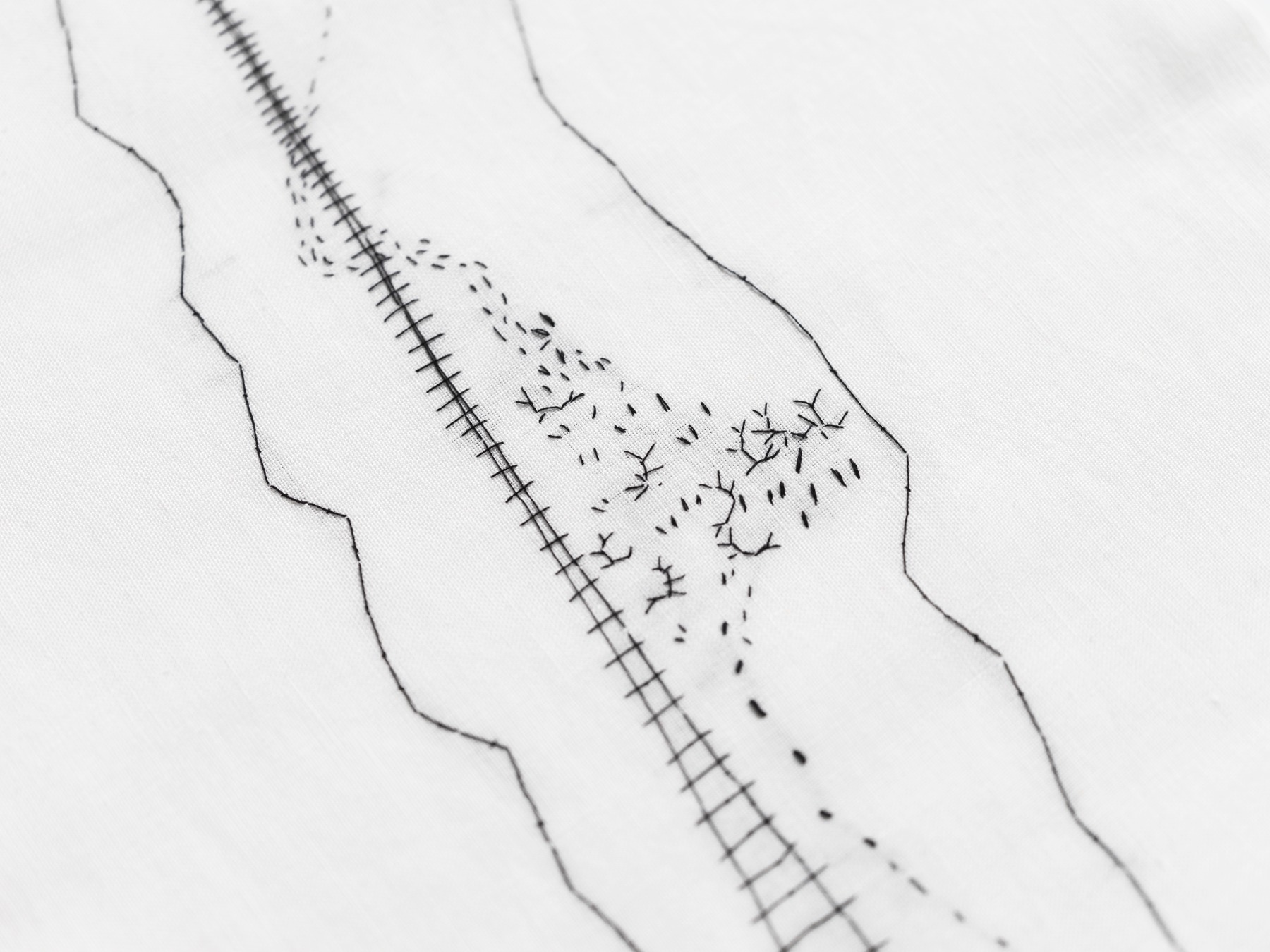

Britta Marakatt-Labba, “Traces II”. Detail. Photo: Annar Bjørgli / National Museum of Norway

The train tracks were destroyed twice, and the company declared a loss of several billion kroner. Some thought it was sabotage. It is not sabotage as such that humans have been there, but it is nature that is sabotaging. We have global warming now. When it is both cold and hot, there is a lot of sliding down mountain sides, and it is clear that the railway track is not very strong.

We have had huge hurricanes, with winds of 37 meters per second. Everyone talks about green energy - but is it that green? You have to dig more to make the batteries for electric cars, for mobile phones. Then you destroy even more. In my area they have found graphite, the municipality said no so far, but you don’t know if the government says yes. And there are Australian and Canadian companies that come and dig. In my area they found cobalt, and that is the worst. So we have a lot to demonstrate against, it’s going on today.

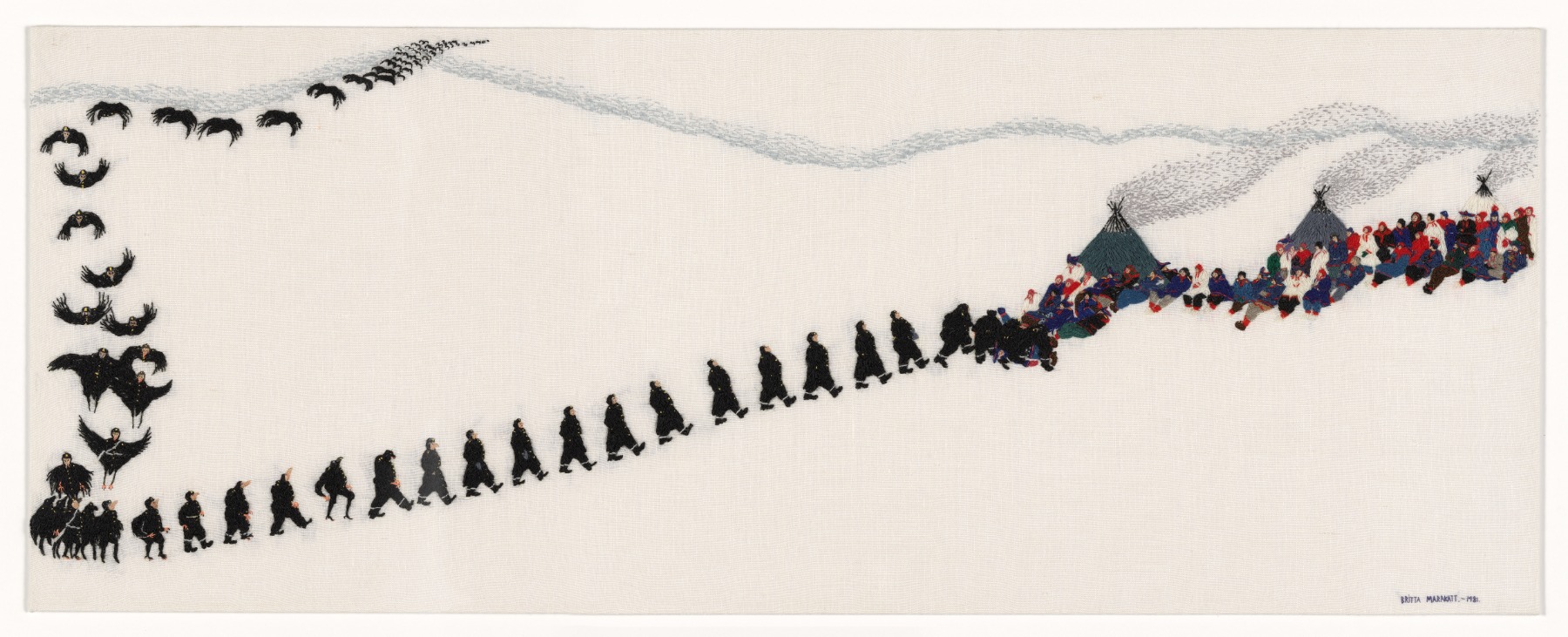

“Garjját”/“Kråkene”, 1981. Photo: Andreas Harvik / National Museum of Norway

In the 1980s, you took part at the legendary demonstrations against the construction of a hydroelectric power plant in the Alta - Kautokeino River.

In the recent Thomas Jackson’s film Historja you say that the Sámi people are born into a struggle, but today we have the last one - the struggle against the environmental crisis and climate change. What can one learn from the Sámi people?

Everyone talks about the need to save energy. I grew up in an environment where people always thought about saving. You don’t want to waste energy that you don’t need. I think of the small streams that turn into big rivers and finally there is the sea.

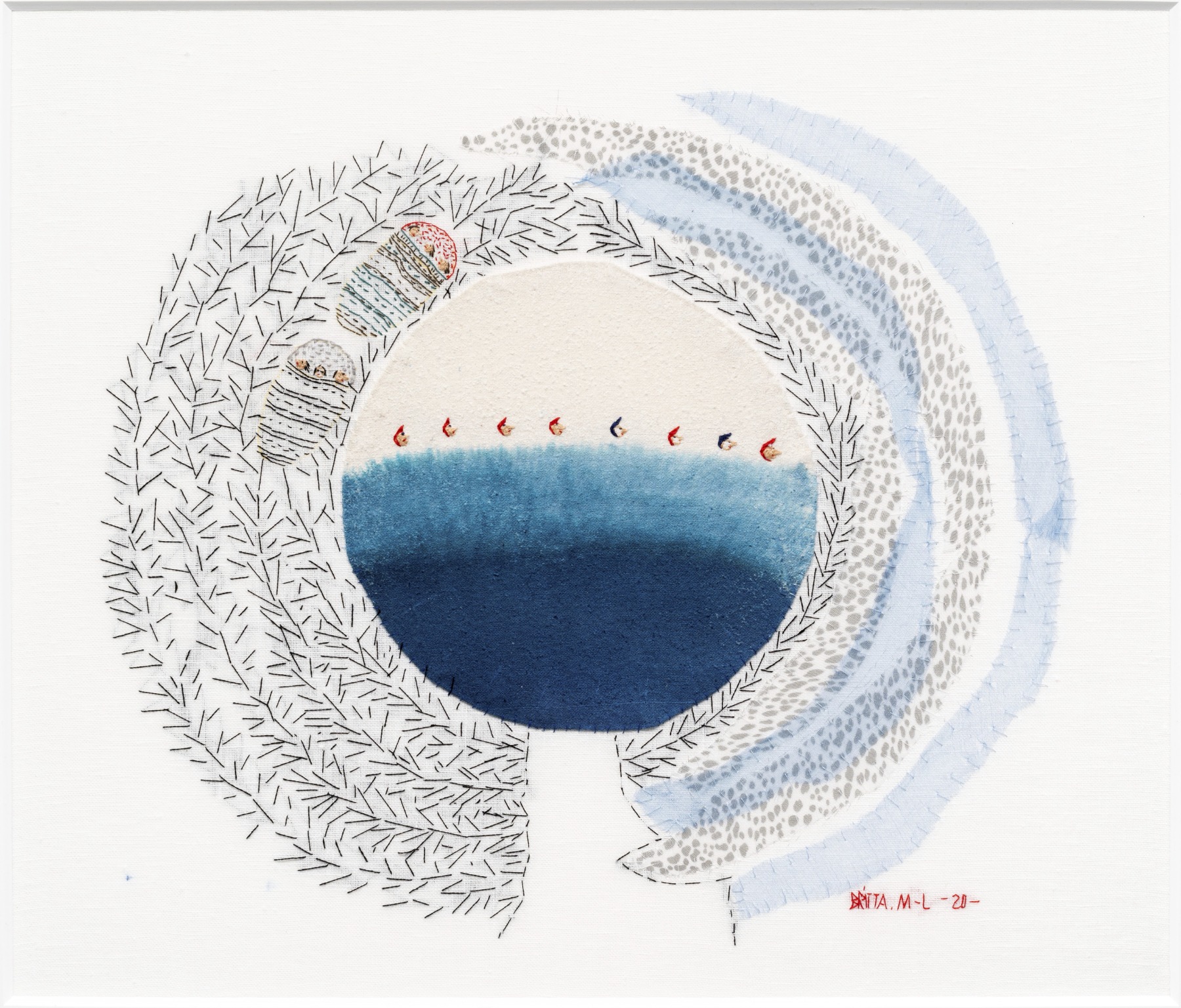

“Gjerdu II”/”Circle II”. Photo: Dag Fosse / KODE Bergen Kunstmuseum

I grew up with the idea that you should always think about the environment. We have never built too big houses and we have been frugal with what nature gives us. I believe that society at large can learn from us to try to read nature. What is nature telling us now? The animals are very sensitive. Birds can behave in a certain way. You can actually learn a lot from nature.

In Australia, when the fires spread, they should have listened to the aborigines because they have special ways of making folds out of eucalyptus leaves that prevent the fire from spreading, so there is a lot of knowledge. I think like this when you have seminars and meetings about climate change. It is extremely rare that Sámi are invited to these, while they have deep knowledge which could be useful.

Britta Marakatt-Labba. Photo: Ina Wesenberg / National Museum of Norway

Ekaterina Sharova is a curator, educator and writer based in Oslo, Norway.

Being raised in the Arctic region, she works with decolonial feminist ecologies, alternative knowledge systems, reappropriation of memory and repair.

She is a co-founder of the Arctic Art Institute.