Human cameras

Interview with an artist Lindsay Seers

Lindsay Seers is an artist from the United Kingdom, and since 2012 has been developing a collaborative artistic practice with Keith Sargent. Their work spans across several media, with a focus on the nature of consciousness and how it shapes human life. Seers and Sargent have shown their work internationally in museums, institutions and contemporary art events, including the Venice Biennale, the Hayward Gallery (UK), Kiasma (Finland), Bonniers Konsthall (Sweden), and Turner Contemporary (UK).

Their exhibition Vamp(yre) Reality is part of this year’s Riga Photography Biennial (RPB), and is on view from April 19 until June 2. Arterritory spoke to Seers about her and Sargent’s collaborative practice and the exhibition in Riga.

Lindsay Seers, Keith Sargent.

Vamp(yre) Reality. Exhibition view, 2024. Photo: Kristīne Madjare

The exhibition Vamp(yre) Reality opens this week as part of the Riga Photography Biennial. How did your association with the Biennial begin?

I can’t recall the string of connections that led me to apply to go on a residency at Braziers in the UK. Braziers Park is an artists’ collective that started in 1995. The collective works in a multi-disciplinary way with artists from around the world. The focus remains firmly rooted in art, environment, and pushing boundaries – embracing differences whilst celebrating a common cause. It was in this residency that I met Inga Brūvere (the programme director of the RPB) in 2002.

Lindsay Seers, Keith Sargent.

Vamp(yre) Reality. Exhibition view, 2024. Photo: Kristīne Madjare

Can you talk a bit about the ideas behind the exhibition and its connection to Riga?

There are four films, which have differing functions: one using the body as a camera – as a performance and its implications; one about the relationship between the iPhone and its use as a camera; one using AI to let the dead speak; and lastly, one with the use of VR, to let the viewer be within the camera/projector, viewing the dead images.

The presence of the Human Camera work in Riga came out of the blue from a phone message: a few months ago, Inga Brūvere suggested I revisit these works. I have made many, many works on this idea of using my mouth cavity as a way of ‘ingesting’ images. The body as a vessel – as an instrument, receiver and transmitter – reflexively parallels the recording and projecting mechanics of film, photography and video, which is a consistent feature of our work. To make a picture, I first climb into a lightproof bag. I place a pre-cut piece of black and white or colour-negative paper at the back of my mouth, then, using my lips or my hand as a ‘shutter’, I make the exposure.

As for the film about our relationship to an iPhone, I was interested in consciousness and how it is what underpins any semantic human thought, and my intention was to investigate what technologies (specifically, the iPhone) do to our consciousness. The exhibited projection work takes the frame of an iPhone as the harbinger of the enormous escalation of current image and sound capturing.

The third piece, Revamping Reality, is a work that specifically draws on the historical context of images from Riga. It involved a process of finding old photographs with the help of Inga, and bringing them to life with AI. The trope of ‘uncanny valley’ pervades the work. The found album is full of actors who have something to tell you.

And then, lastly, Revamping Reality VR is a 360-degree version of the main Revamping Reality film. The viewer enters/becomes the camera/projector, watching the images of people long since dead. These dead actors have become re-animated through AI, and had a discord channel on their imaginary existence even before their ‘births’.

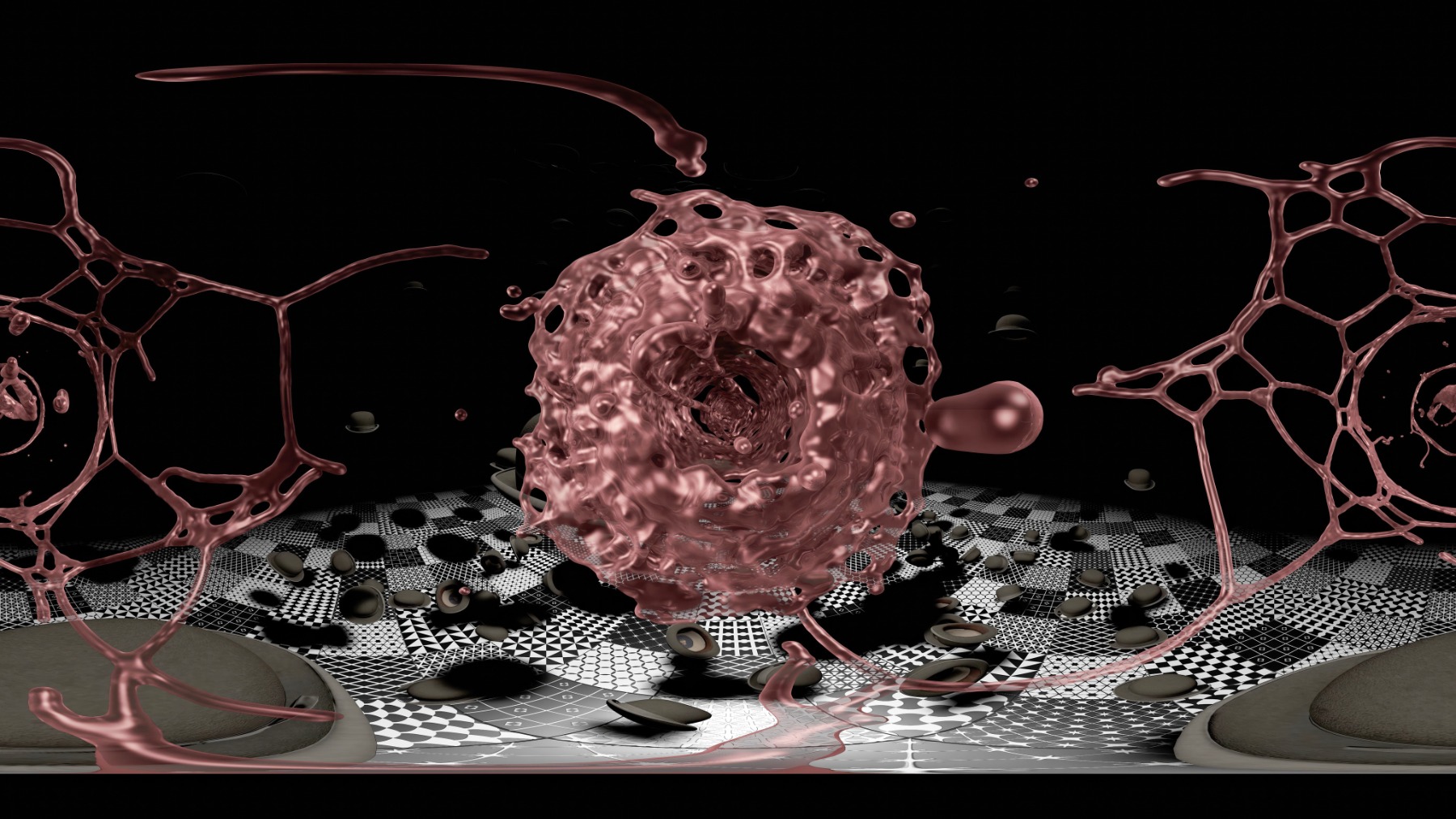

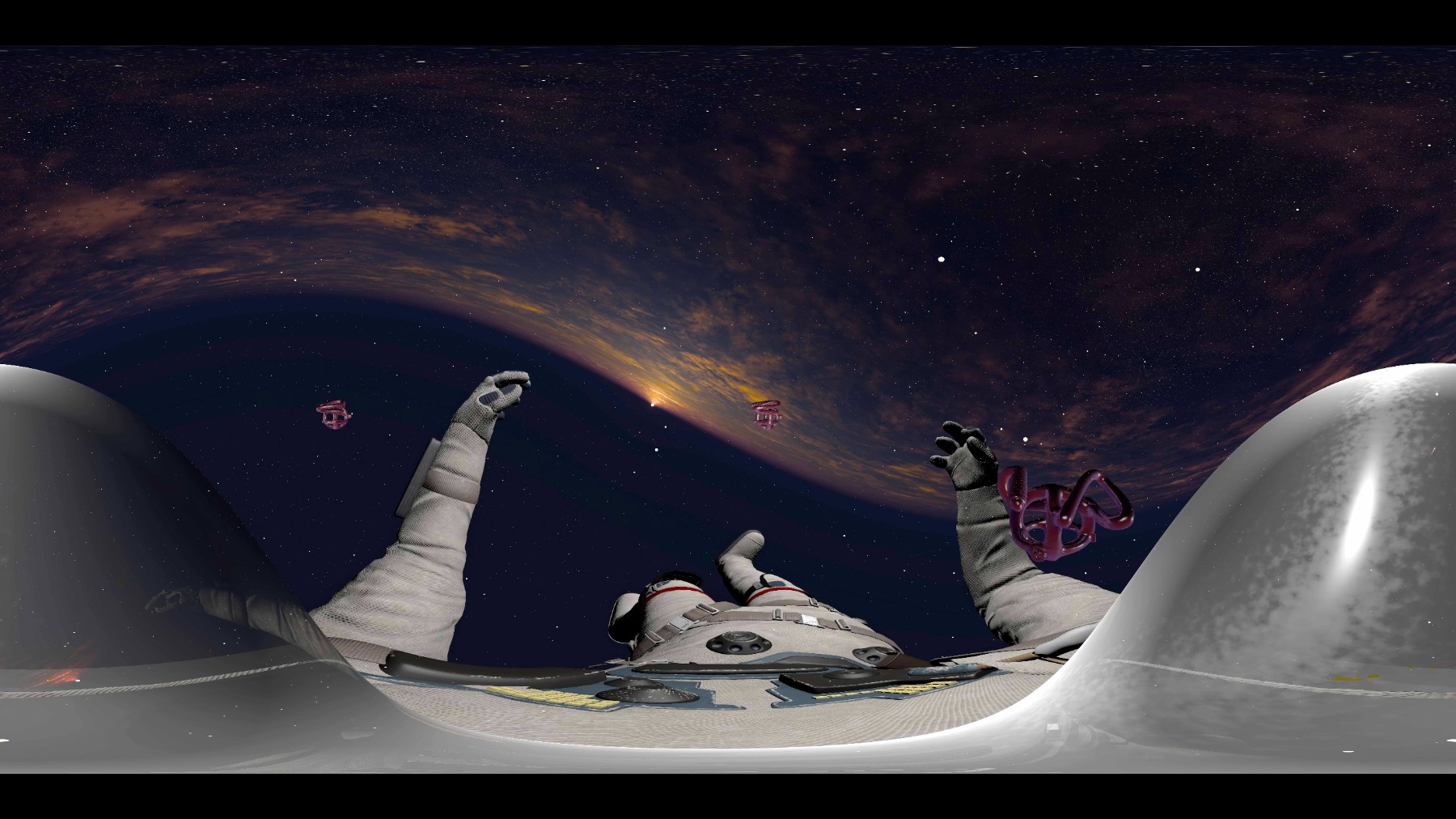

Lindsay Seers, Keith Sargent.

Vamp(yre) Reality. VR

Lindsay Seers, Keith Sargent.

Vamp(yre) Reality. VR

You speak a lot about your interest in consciousness, and the exhibition statement makes references to the French philosopher Henri Bergson – how has he been influential to your work?

I was already making work in which I became a human camera when I was at the Slade School of Fine Art in 1994. The Braziers connection with the Triangle International Workshop at Braziers led me to another Triangle residency in Asuncion, Paraguay, where I read Bergson every day for a month. I also attended another Triangle residency in Mauritius, which is where I grew up.

Bergson has a very specific relationship to the unique quality of each individual. He speaks of how when we touch one of our hands with the other hand, we have the the sensation of our interior and exterior simultaneously – we fold in on our selfhood.

Bergson, however, thought that the photograph would never be able to convey the intensity of being present; he writes about how, no matter how many photographs of Paris you take, you will only know Paris when you step out and smell the air and move through the streets. He insists that we need to assess things through quality (subjectivity) not through quantity (measurement).

I reconsidered the three rules suggested by Bergson: quality, quantity, and Élan vital (vital force). I used a method by taking an action – creating a method to challenge the coherence of storytelling.

It would take too much writing space to talk about the point of methods, but I took a policy that was derived from chance and a set of what seemed like coincidences. In brief, at the time, I was in the British School of Rome at another residency, and I was chasing down Queen Christina of Sweden, who was heralded as an alchemist (thinking of alchemy in its true sense – as raising consciousness). During the Renaissance, the world was considered to be a stage in which we are all actors. At the BSR, I was reading an esoteric book with a foreword by Rudolf Steiner about alchemy. In the text, Steiner spoke of how the spider works alone and will never be enlightened, but the bee has a hive mind, and through this shared mind, bees can raise the consciousness of the hive. At this point, a huge bumble bee came into my studio and later died on the windowsill. From this, I decided on an artistic policy: whenever I found a dead bee, I would collect it and then label it by drawing it. I would ensure that the thought that I was having at the time would appear in the work. The intention was, ultimately, to fracture the nature of consciousness – of storytelling – as something not coherent but in a constant state of flux.

Lindsay Seers, Keith Sargent.

Vamp(yre) Reality. Exhibition view, 2024. Photo: Kristīne Madjare

Vampires appear in this exhibition, and they’ve been a subject in your art before. What draws you to these very symbolic creatures?

The connection to vampires came from both the artist John Hilliard and the writer Jean Fisher, whom I have met. Fisher uses the metaphor of the vampire when speaking of the effect of photography – sucking the blood out of life and sustaining a presence as eternally dead but still omnipresent. When I take the photographs in my mouth, they are red due to the light passing through the blood in my cheeks. What we found interesting was that we have been using AI for the Riga show to make the photographs have a voice. In the program we used, the AI says it’s ‘revamping reality’ while the file is rendering. Hence the title, Re(vampyring) Reality.

Lindsay Seers, Keith Sargent.

Vamp(yre) Reality. VR

The role of photography in everyday life drastically changed from the moment that smartphones and social media became ubiquitous. Do you think that has influenced it as an art form, and if yes, in what way?

Dopamine – a pleasure hormone – is a driving force for our subjectivity; it is the drug that shapes our emotional states that remain unanalysed. I believe that the iPhone mirrors the way that the brain functions in the way that it feeds off an incoherent stream of ideas that are quickly consumed and unchecked against reality.

I am currently reading a fantastic book called Thinking Fast and Slow, by Daniel Kahneman. Incidentally, I was following a ‘bee find’ in the street just outside the Waterstones bookshop that was across the street from where I had studied at UCL. I walked into the shop, ended up in the stationary section, and there, shoved amongst the craft kits, was this book. The book shows how we construct our beliefs with very little evidence. In fact, a monkey throwing a dart is more likely to be correct than a financial analyst, and an algorithm will almost always be more correct than a human. We believe completely unfounded truths on the slightest of evidence. This is then made even more concrete by being amongst others who also hold utterly unsubstantiated and irrational prejudices, and so we are constantly reinforcing these ‘truths’.

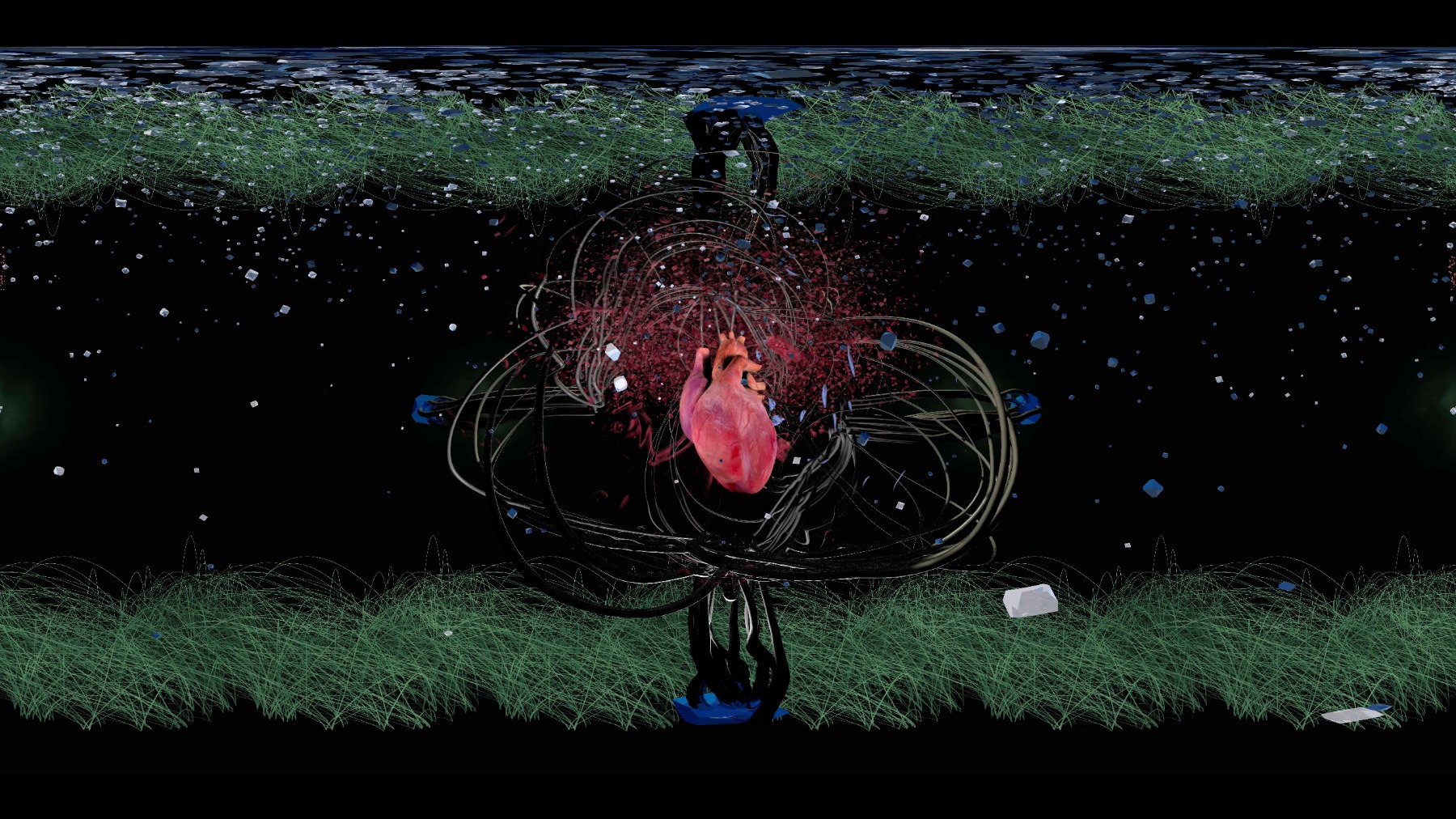

Lindsay Seers, Keith Sargent.

Vamp(yre) Reality. Video still

You and Keith Sargent work together as an artistic duo. What is your process like? How do you collaborate?

We work to our strengths. We constantly talk and challenge one another – we search down the conceptual ambitions of the work. Our principle position is to break down the duality of fact and fiction; this duality does not exist. We try to avoid tropes (unless for comical reasons), and question every choice regarding the installations and types of technology. We consider that content and form should be in balance. We have often made huge structures in order to contain the works that we have constructed. In these structures, everything matters – the light levels, the sound, the image, the seating, the temperature...

Lindsay Seers, Keith Sargent.

Vamp(yre) Reality. Video still

What is your next project?

It is hard to say, with the cost of living crisis looming and the constant threat of escalating world-wide wars and unrest… And climate change is also terrifying. I have been campaigning for fair pay for artists for about 15 years. The National Galleries, which we work with, rarely pay the artist for their labour. I would like to change things for the next generation, but it is a hard nut to crack. The UK government has an exceptionally poor relationship to contemporary art; in fact, both visual literacy and even literacy itself are shockingly poor – theatre and sport are at their focus for funding. We can only aspire to more art-centred economies, such as those in Norway.

Lindsay Seers, Keith Sargent.

Vamp(yre) Reality. Video still

You have exhibited work internationally in large institutions and museums, and have also been a lecturer at several art schools. What would be your advice for artists who are just starting out?

The non-fungible token is not an answer and relies on the super rich artists who can make more money for a single artwork. The National Portfolio Galleries, which are publicly funded spaces, will generally pay for technical staff but not for artistic labour. The general idea is that we, artists outside of the gallery systems, are grateful to be shown at all – that it is an honour. The artist is at the bottom of the food chain, leaving artists like me – from a working-class background, with no chance of using nepotism or having the luxury of being independently wealthy through family money – having little chance of an income through art. As Hito Steyerl has so eloquently shown us: art is where the super rich hide their wealth in warehouses at secret locations.

A whole new way needs to be established, with artists working with other artists who do not come from wealthy backgrounds. Perhaps this can be achieved by collectives that can demonetise art as an object but create it through a process. This means finding an economy that can stand as a proxy. Perhaps the Braziers model is the answer? That is, the drawing together of diverse participants that learn from one another, and where each participant has a voice.

Lindsay Seers, Keith Sargent.

Vamp(yre) Reality. Exhibition view, 2024. Photo: Kristīne Madjare