How much radical softness is there in Estonians?

An interview with psychologist Jüri Allik

On June 26, fifteen Estonian artists opened a joint exhibition titled "Radical Softness"* at the Lisbon Contemporary Jewellery Biennial. The jewellery and exhibition design conceptualise a world where artists explore how to soften prevailing cultural clichés.

Estonian jewellery has become a mark of quality in the jewellery world, a meaningful and sensitive statement in the fast lane of superficial ideas. "Radical Softness" brings together artists with the backbone and suggestiveness to address significant themes that touch on the fundamental principles of being. In an era of cultural and identity wars, a thoughtful pause holds increasing weight. Fifteen jewellery artists make an existential statement through their material, inviting us to pause and seek answers — and the resilience to remain true to oneself — more from within than without.

I asked psychologist Jüri Allik to shed some light on the interconnections between nationality and personality. Jüri Allik is the author of many articles and monographs, a member of the Estonian, Finnish and European academies of science and professor of experimental psychology at the University of Tartu.

I invited 14 other Estonian jewellery artists over for a visit. Over some pie, we tried to articulate the common features. We winnowed it down to “radical softness". That phrase seemed to capture something intrinsic to being Estonian, tending to be introverted and stoic, contemplating the ways of the world with empathy and (after some reflection) relating to it.

Tanel Veenre, “Please”: brooch, seashell, carved camel bone, gold.

As a psychologist, how do you view this phrase we came up with, “radical softness”?

Radical softness seems like a nice metaphor with good resonance. In physics, tough softness might be called elasticity: a body’s property to change shape when a force acts upon it, and in the absence of the force, to return to its former shape.

Could that phrase be translated into a personal psychology context?

Perusing the literature quickly, I'd be hard-pressed to come up with a personality trait that could be called elasticity or tough softness. Years ago, Suzanne Kobasa constructed a parameter called hardiness that measured people’s ability to tolerate stress. But I wasn’t able to find a precise match for “tough softness”. It’s definitely not a unique trait but some combination of other well-known qualities.

There is quite a broad consensus among researchers that there are only five major, non-interdependent personality traits: these are neuroticism (N), extroversion (E), openness (O), agreeableness (A) and conscientiousness (C). These big five traits consist of more specific facets. Neuroticism is expressed in anxiety, vulnerability and anger. Extroversion is signalled by cheerfulness, a love of crowded settings and a desire to self-actualize. Neuroticism, whose opposing trait is called emotional stability, could indeed also be called tenaciousness, if we see it as the ability to withstand strain and stress.

But a possible shade of meaning of tenaciousness is conscientiousness. Its prototype is the ability to withstand temptation, which would appear to require willpower.

I should also mention that one source of modern personality theory is a lexical approach. One of its founders is considered to be Gordon Allport. In 1936, he and Henry Odbert went through the Webster dictionary and wrote down all words that suggest some general and constant behavioural tendency that helps a person cope in life. There were 4504 words like “sad”, “happy”, “conciliatory” or “determined”. People were asked to rate themselves or good friends of theirs as to how aptly the words described them. As it turned out, out of those thousands of words, there were only five adjectives completely independent of each other, which can't be expressed in terms of other ones. Although there are nuances and variations, there are a limited number of building-block words with all the others around them.

One might think that the discovery of only five major personality traits might make the whole discipline very boring, but its significance is comparable to the development of biological taxonomy. No longer are there thousands of adjectives that can be arranged in alphabetical order. Instead there are major classes, which are divided into smaller orders, families, genera and species.

Can conscientiousness also mean movement along the axis of closed-mindedness? It’s only a few steps away from fundamentalism, which is a rigid fixation on principles.

Tenacity can be thought of also as mental rigidity, which instead points to another trait characterised by being closed-minded: resistance to changes, conformism and clinging to traditions rigidly.

The meaning of terms in everyday language does not always match how psychologists use them. We say meelekindlus (literally resolve or determination) in Estonian to refer to the Big Five trait of conscientiousness is most certainly not related to Openness (or closed-mindedness), because that is another one of the Big Five and independent of conscientiousness. At its core, conscientiousness is the ability to withstand temptations. It is above all the ability to maintain discipline, be consistent and finish what one started. That can largely be summarised with the word “willpower”, which appears to be the main goal of education science to cultivate. Very many studies have shown that conscientiousness and openness to new experiences are independent of each other. Among people with high conscientiousness, there are equal numbers of those who are open and closed to new experience. Conversely, people with high openness include both conscientious people and ones who cannot withstand temptations and urges.

I recently watched a great performance at Von Krahli Theatre, Fundamentalist, which seemed to be very much in the zeitgeist. Extremism is more clearly rearing its head, maybe it’s not so much quantitatively predominant but it’s very vocal, almost cartoonish, on (social) media. I was gripped by the question of how to tell where the boundary runs where conscientiousness becomes blind faith and fundamentalism. How to recognize if I am becoming a fundamentalist, sealed in his own information bubble, and nodding along with proponents of other extremist views in my echo chamber?

Right after the end of WWII, Theodor Adorno wrote The Authoritarian Personality, which posited an independent personality type that is fixated on traditional family values, obedient to a strong-armed leader, sincerely believes conspiracy theories and thinks people are inevitably against each other in war and some definite group of people are to blame (Jews, communists, Freemasons, homosexuals etc.). Today, scholars tend to believe that authoritarianism is not one specific type of person but a set of social attitudes and core values that has taken shape over time. In that sense, it is more a characteristic of society and culture, not so much a person’s position in the cultural matrix of attitudes and values.

After Estonia regained independence, people there were mainly concerned how not to go hungry, how to ensure safety and physical security. Perhaps the only good thing the Soviet era did was that it fostered deep distrust in any authority figures. That scepticism helped us survive – but at the cost of a very low trust level, but trust is considered the stuff that oils the wheels of a society. Over the last 30 years, we have moved to the other edge of the map of values, the side where all the Nordic countries are found, led by Finland, the world’s happiest people.

How accurate is the notion that Estonians don’t rush to be early adopters of anything? That they instead let more fervent folks have their rush and learn from their triumphs and failures.

Yes, one of the favourite Estonian proverbs is that wise man doesn’t rush. Impulsive action, leaping without looking isn’t part of our national stereotype, like it is for some of our neighbours. But that doesn’t mean that Estonians resist everything that is new. For some years now, Estonia has seven prominent tech companies with a value of over a billion dollars. Estonia has more start-ups per capita than anywhere else in Europe.

If you were to compare Estonians to Nordic peoples (i.e. Scandinavians and Finland), what does our mindset have in common? What are the differences?

National character has long been at the centre of interest for psychologists and anthropologists. To the common person, it seems that every nation has its own distinct personality. Everyone “knows” that Italians are hot-blooded, Finns are taciturn, Germans lack a sense of humour and Greeks don’t follow rules. Researchers were sure that national stereotypes were exaggerated nevertheless national character traits that really existed.

We managed to be a part of the international project “National character does not reflect mean personality trait levels in 49 cultures”, which showed that national character is nearly always a diction, nor does it reflect the actual mean personality traits of a people. For instance, the peoples in Russia’s neighbourhood have developed their presumptive national character on the basis of what they think of Russians. For neighbours, though, Russians are seen as intrusive, noisy and lazy, and thus Estonians are above all, not-Russian: they are introverted, quiet and hard-working.

Erle Nemvalts, “Anatomy of Anxiety”: crown, cast iron.

Our exhibition is being held in Lisbon, which is not just by chance. The intangible bond with the artist community there has evolved over the years. I was surprised to sense that the Portuguese mindset was very similar to the Estonian one. A small country on Europe's periphery on the sea, in the shadow of a large neighbour. Tending to be introverted, melancholy (the Portuguese word saudade – longing, and the folk music genre fado), unlike their neighbouring country, people rarely shout on the street. Might there be some scientific truth to my impressions?

When we last compiled a map of world distribution of personality traits, Estonians and Portuguese could not be more different. Portugal has a high level of neuroticism (emotional instability) while Estonians are tougher withstanding stress. The discrepancy on other axes was not as great, although the Portuguese did appear slightly more closed-minded and introverted compared to Estonians.

But that doesn’t mean that we might not have a spiritual kinship with the Portuguese. I have been to Portugal many times and felt very comfortable there. There is probably something in the culture and way of interacting in Portugal that strikes a chord with Estonians.

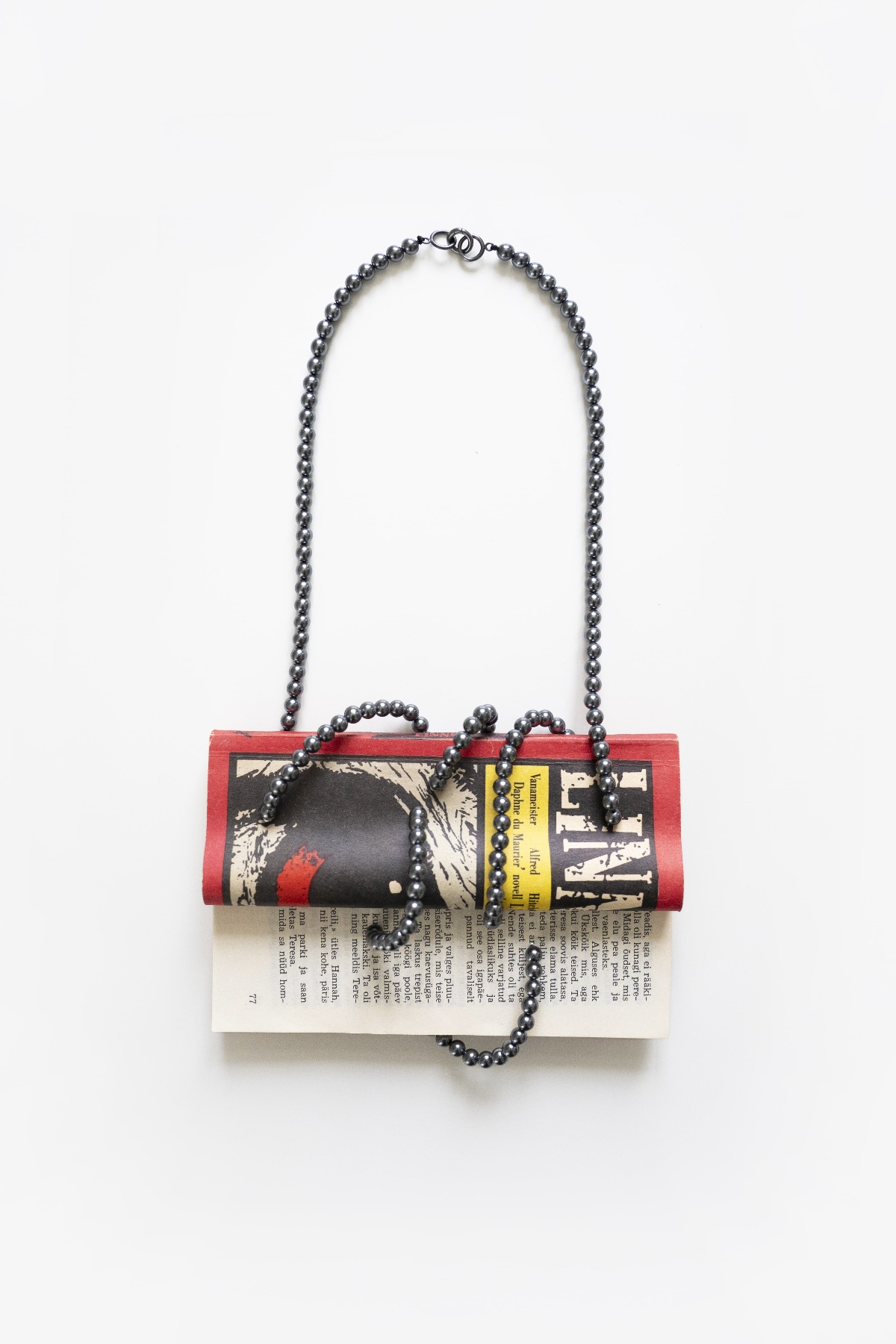

Hansel Tai, “Vintage Book Entitled ‘Linnud – Daphne du Maurier’”, necklace: mother of pearl, thread, oxidised silver.

Is the “Estonian mindset” a thing? How much can we draw generalizations along ethnic lines when assessing a certain group of humans? You’ve noted that intercultural differences are nearly eight times lesser than the differences within a single culture. But societal and social influences are mainly related to countries and peoples.

One observation that I haven’t noticed before was revealed in our research: the average differences between cultures or countries are many times less than what separates two randomly selected people living in the same place. In other words, the identity or personality of one Estonian varies from that of another randomly selected Estonian much more than an average Latvian’s personality differs from that of an average Estonian. The differences between cultures are minor compared to the great intercultural differences.

You’ve also concluded that the climate does not affect the emotions and national character stereotypes do not align with mean profiles. But we see stereotypes come into play every day: Demonstrations in Paris, even ones that spill over into riots, are common, while Estonians tend not to take to the streets to speak their mind. A handful of people standing on the government hill in Tallinn carrying signs are regarded with indifference, perhaps even seen as cranks. Why don’t Estonians usually show their political sentiment on the streets?

Sitting in an armchair, it occurred to Baron de Montesquieu that in a cold climate, men become confident, strong and industrious. A warm climate makes people lazy, weak and complacent. Since that time, there have been various attempts with different degrees of success to demonstrate the climate’s influence on people. But the evidence is uneven; the effects of climate, if any manifest at all, are quite miniscule. It’s commonly believed that sunny weather makes you happy and rainy weather makes you downcast.

At the time, we were working on a study where over a two-week period, at various intervals we asked test subjects what they felt. On the roof of the physics building in Tartu was an automatic weather station, so we could check whether a change in the weather was somehow tied to fluctuations in mood. Contrary to the popular myth, happy and sad moods didn't depend on sunshine, barometric pressure or rain. The only thing that did slightly depend on the weather was fatigue. Older people became more tired than younger people in rainy weather.

That of course does not mean that climate can’t have some influence on people’s attitudes, values and activities. For example, Evert van de Vliert from the University of Groningen noticed that climate is best characterised by distance from the equator. In the warm climate of the tropics, cultures have a tendency toward collectivism and greater power hierarchy. But in addition to warmth, our mindset is also affected by means of subsistence. Rice cultivation is twice as labour intensive than wheat growing. It’s hard to grow rice without help from others. It has been remarked that Chinese rice growers have a more robust social network than wheat growers.

Scepticism has been highlighted as a stereotypical Estonian personality trait. It can be treated as a reaction to lack of trust. To simplify, it isn’t hard to discern Estonians’ attitudes toward foreign rulers, the trauma of the Soviet occupation, the deprivation of peasant origins… Has joining the capitalistic democratic fold with greater social trust reduced Estonian scepticism? You’ve written that democratic institutions and traditions favour the development of personality traits related to openness and, in particular, the ability to trust strangers. How do you perceive the relationship between trust and the Estonian identity and how it has changed in society?

Anyone can consult the World Values Survey database and see how Estonians responded compared to 89 other countries to the question of whether most people can be trusted. The question of what is meant by “most” might cause confusion, so the eighth wave of the study asked additional questions distinguishing between perfect strangers, people with different religions and different appearances. Trust is something that societies can allow themselves starting from a certain level of human development (affluence, education and life expectancy) and thus trust among people is Estonia aligns with what could be expected based on the theory. Our level of trust is still lower than Denmark, Sweden or Finland but at the same level as Italy, Belgium and France. In short: following the restoration of independence, Estonians' trust has grown even faster than might be predicted by human development.

As a culture-centred artist, I am likely to seize on cultural influences. I often use the reference “Protestant” when describing Estonians: people who forgo gratification today for the sake of tomorrow (i.e., working through the summer to prepare for the winter), a practical and coolly rational outlook on life. Protestantism is reflected by Estonians’ view of what a “proper” person is. I think you tend to have reservations in this regard: “/…/ the average conscientiousness measured for countries (the trait that indicates people’s industriousness, motivation, propriety and self-discipline) should be related to the country’s affluence, the accuracy of clocks in banks and the speed of its postal service. In actuality, the connection seems to be inverse: countries in which people see themselves as a bit sloppy, undisciplined, where people are not workaholics, the quality of life is in fact better and the post is impeccable.”

Coming back to an even more simplified view of the big picture and projecting Protestant practicality on to the map of the world, it is obvious that nearly all successful economies – from the boundaries of colonial empires and the map of Europe – have Protestant roots. How much do you perceive this kind of Protestant outlook on life as being present in the attitudes of Estonians?

On the World Values Survey map, Protestant Europe stands quite separate from the rest of the world, including from Catholic Europe. The three Baltics are moving in the direction of Protestant European values, passing through the Catholic countries' zone on their way there. As to where Estonia will hopefully end up soon, these are values related to self-expression and self-actualization. On the other values dimension – secularism and rationality – we are already close to the top. We have thus realized that instead of blind belief in religion or party dogma, it is wiser to organize our affairs on the basis of rational, comprehensible rules. This axis of secularity and rationality could easily also be called a Protestant attitude to life.

Piret Hirv, “Convention”: object, cast iron.

One cliché that people relish using when describing Estonians to foreigners is our specific type of village structure. Around the Lake Peipus shore (and incidentally this type of village is seen in other places in Europe) people live in a tight cluster, along a single street, but in the rest of the country, a traditional Estonian village is one where you can only see the neighbour’s chimney smoke. Homes were very far apart, households had minimal contact with each other. What does this say about us? How many of these attitudes rooted in peasant life have spread to the city and how fast has urbanization changed us?

A work by Geert Hofstede (1928–2020), who held an honorary doctorate from the University of Tartu, Culture’s Consequences (1981) became the gold standard for cultural studies for many decades. Comparing cultures with each other, the greatest differences are almost always found in attitudes and values, which can be characterized by the opposing poles of individualism and collectivism. In collectivist cultures, people put family, clan, people, religion or state higher than personal interests. In individualistic cultures, people proceed from personal life goals which do not presume subordination to external authorities.

A village community is structured on the principle that no one has private land. Everything belongs to the community in common. If so, there is no reason to establish dispersed villages where people build a farm in the middle of their private lands. Individualism without private property is an oxymoron.

For a long time, it was believed that individualism had its dark side, egotism, which would gradually destroy the cohesive force in a community. That force could also be called social capital, which in everyday language is called trust. Sociologists have noticed that without mutual trust, no economic or other transactions would function. So individualism was seen as a danger that undermines the foundation on which modern society is built. To us, the fear seemed unjustified, since it turned out that individualism does not destroy social capital but on the contrary, individualism presumes people have the autonomy and responsibility needed to form social bonds.

* The exhibition "Radical Softness," curated by Tanel Veenre and showcased at the Igreja da Madalena church, features: Darja Popolitova, Ketli Tiitsar, Erle Nemvalts, Eve Margus, Hansel Tai, Julia Maria Künnap, Kristi Paap, Kristiina Laurits, Maarja Niinemägi, Maria Valdma Härm, Nils Hint, Piret Hirv, Taavi Teevet, Tanel Veenre, and Villu Plink.

Title image: Taavi Teevet, Ultima Fides I, 2024.