Difficulty in grasping the contemporary

Aiste Liuka Jonynaite

Reflection on the Baltic Triennial. An interview with Paul O’Neill, an Irish curator, artist, writer and educator

The idea for the following interview emerged from my personal interest in discourses around exhibition making and the seeming lack thereof in the context of the Baltic Triennial. As an art historian and curator who received training in England, I engage mostly with the histories of itinerant exhibitions as they appear in scholarship dominated by the English language. These histories are notably based on the socioeconomic ramifications of ‘centre’ and ‘periphery’ and consider the shifting preconceptions of contemporaneity in the globalised world. As my professional career led me back to Lithuania, I wondered how they may apply in the Baltic region. Specifically, within the context of the Baltic Triennial, described on the CAC Vilnius website as ‘one of the most ambitious contemporary art events in the Baltic region.’ While the topic of how the international art world is negotiated within the local artistic communities in the Baltic countries remains extremely broad, I decided to scratch its unexplored complexities by speaking to Paul O’Neill. Paul remains one of the most influential writers and educators on curatorial practices today. His The Culture of Curating and the Curating of Culture(s) (MIT Press, 2012) provides a profound insight into how our perception of art has been transformed by curating, and since its publishing, become one of the seminal read in curricula of many curating courses worldwide. Most importantly, Paul recently has expanded his significant career in curating, writing, and teaching to the Baltic and Nordic regions. Since 2017, Paul has held the position of Artistic Director of PUBLICS, a curatorial agency in Helsinki, and the Visiting Professor in MA Curating at the Latvian Academy of Fine Arts.

The Baltic Triennial has been a pivotal contemporary art event of the Baltic region since the early 90s. It has a distinct history as it started as an experimental exhibition of non-conformist art in 1979 before the global ‘biennialisation’ wave’ of the 1990s. However, its history, legacy, and wider impact is yet to be explored. I wanted to address the lack of reflection on the Baltic Triennial as a form of exhibition- making. Broadly speaking, what are the potentialities of biennials, triennials, and itinerant exhibitions for what is called the ‘peripheral’ geographies or locales?

Historically, the biennial exhibition-form is connected to colonial histories and their on-going impacts and legacies. They emerge in colonial centers of western eurocentric modern art of the late 19th and early 20th centuries with a national representational agenda. The first biennial was founded in Venice in 1895, followed by the Whitney Biennial in New York in 1932. They were founded with an ambition to showcase nations as networked circuits of international art at what was seen at the time as the central locations of the world. Later after the Second World War, other two large-scale temporary exhibitions made claims to power, authority of being centers of the art world, namely The São Paulo Biennial and Documenta. It is important to recognize the long history of the itinerant events. In the 80s a few events countered the supposed universal scope of this exhibition form. In the Global South biennials such as Havana presented art outside of Europe and the US and put continents such as Africa, Latin America, and Asia on the global map. This diversification allowed for smaller-scale, localized biennials to emerge in the cities of Istanbul, Gwangju, and Dakar, among many others. This moment is commonly known as biennalisation. Terms such as ‘biennial’, ‘biennale,’ or ‘mega exhibition’ no longer refer to those few exhibitions that occur perennially, every two years or so: they are now all-encompassing idioms for large-scale international group exhibitions, which, for each local cultural context, are organized locally with connection to other national cultural networks.

At the turn of the century, biennials appeared as the most fluid form of exhibition-making. They made evident wider economic developments such as the global circulation of capital and influences of the booming contemporary art market. Despite any curatorial self-reflexivity in recent large-scale exhibitions that may exist towards the global effects of “biennialization”, the periphery still has to follow the discourse of the center. In the case of biennials, the periphery comes to the center in search of legitimization and, by default, accepts the conditions of this legitimacy. The context of free trade and a reinstated market economy is perceived as a precedent for many biennials in the so-called former Eastern Europe. As with other smaller iterant events, I see the tendency in so Eastern Europe to represent the global developments in art from a local context as an epicenter. Biennials as such tend to focus on global networks of cultural production as their kind of source material and are connected to a hosting city. Regional histories, social, and artistic productions to various extents are relevant even if the biennials include artists from elsewhere. It is worth noting, that when I speak about the region of ‘former East’, I have contexts of such countries as Poland or Hungary or former Yugoslavia, Croatia, Serbia, Bosnia, Herzegovina, and Turkey in mind. I am aware of the curatorial developments in these countries. They have historically been more connected to art scenes elsewhere, curators and art historians there have access to a wider kind of network beyond their immediate locale. The Baltic region I suppose is distinct from them because it was only after the 90s that the artistic exchanges outside the region started taking place. At its inception the triennial did not function as the mediator of the global art economies within the local, rather it was an exchange platform between the artists of Baltic states. Thus the 90’s presented more challenges than exposure to the global markets, it was the moment when the region was exposed to differing systems of art historization and curation.

15th Baltic Triennial Same Day, installation view. Contemporary Art Centre (CAC) Vilnius, 2024. Photo: Kristien Daem

Most biennials reinforce the local and global dimension by leaning on the history of a certain city, which is emphasized in their name. I suppose cities always bring a multi- cultural, ethnically diverse microcosm and therefore create an apt ecosystem for heterogenous co-existence. The Baltic Triennial from the outset is not tight to a city, however, is linked to the institution operating in one place, CAC in Vilnius. What kind of perspectives of the local do you suppose it projects?

I suppose there are two ways we can think about the question; in relation to curatorial intention or to wider processes that are beyond the control of an individual or a group of curators. The organizers can choose to engage with certain themes they see relevant and invite artists to participate accordingly. Then the appointment of a curator who has a grasp on the art scenes of all three Baltic countries is important. However, the kinds of decision they make are also influenced by their training and professional exposure, which in the case of the Baltic triennial tend to reflect the local way of exhibition-making itself.

I have been fortunate to see the last three triennials, including Vincent Honoré’s Give Up the Ghost, Tallinn chapter at the Tallinn Art Hall. Also, Valentinas Klimašauskas and João Laia edition in 2021 in Vilnius, and the recent triennial Same Day. Thus, my understanding of the itinerant exhibition is based on these events as well as multiple conversations with people who are much more embedded in the local contemporary and art historical networks of Lithuania, Estonia, and Latvia than I am. I noticed that the Baltic Triennial adopts the wider practice in the region to showcase emerging and historical artists alongside each other. It speaks I suppose to the simultaneous emergence of curating and the field of art historicization after the ‘90s. I think the region is distinct by the development and emergence of curatorial practices and contemporary art history around the same time. Learning that from Baltic artists and curators profoundly changed my understanding of the triennial.

If I could draw a parallel line with the evolution of contemporary art history in Ireland, the contemporary in art history became a relatively recent subject of note after 1968. However, it was not fully contemporized until the late ‘80s, early ‘90s due to access to contemporary art discourses, its education provision and contemporary art markets widening. Ireland was a relatively poor country in the ‘70s and ‘80s. Cultural history was written from Ireland’s adjacence to its colonial occupiers and proximity to North America through its histories of migration. Ireland, like many colonial contexts was catching up and we are all still gett8ng up to speed with other post-colonial, and anti-colonial narratives in terms of global art and exhibition histories.

So, the situation of curating and historicizing contemporary art is not geographically bound to the former Soviet countries exclusively. Nonetheless, the recurrent dialogue with the way art histories have been written in the West and could be applied here as well as following trends of contemporary exhibition making is what brings a particular flavor to the Baltic triennial.

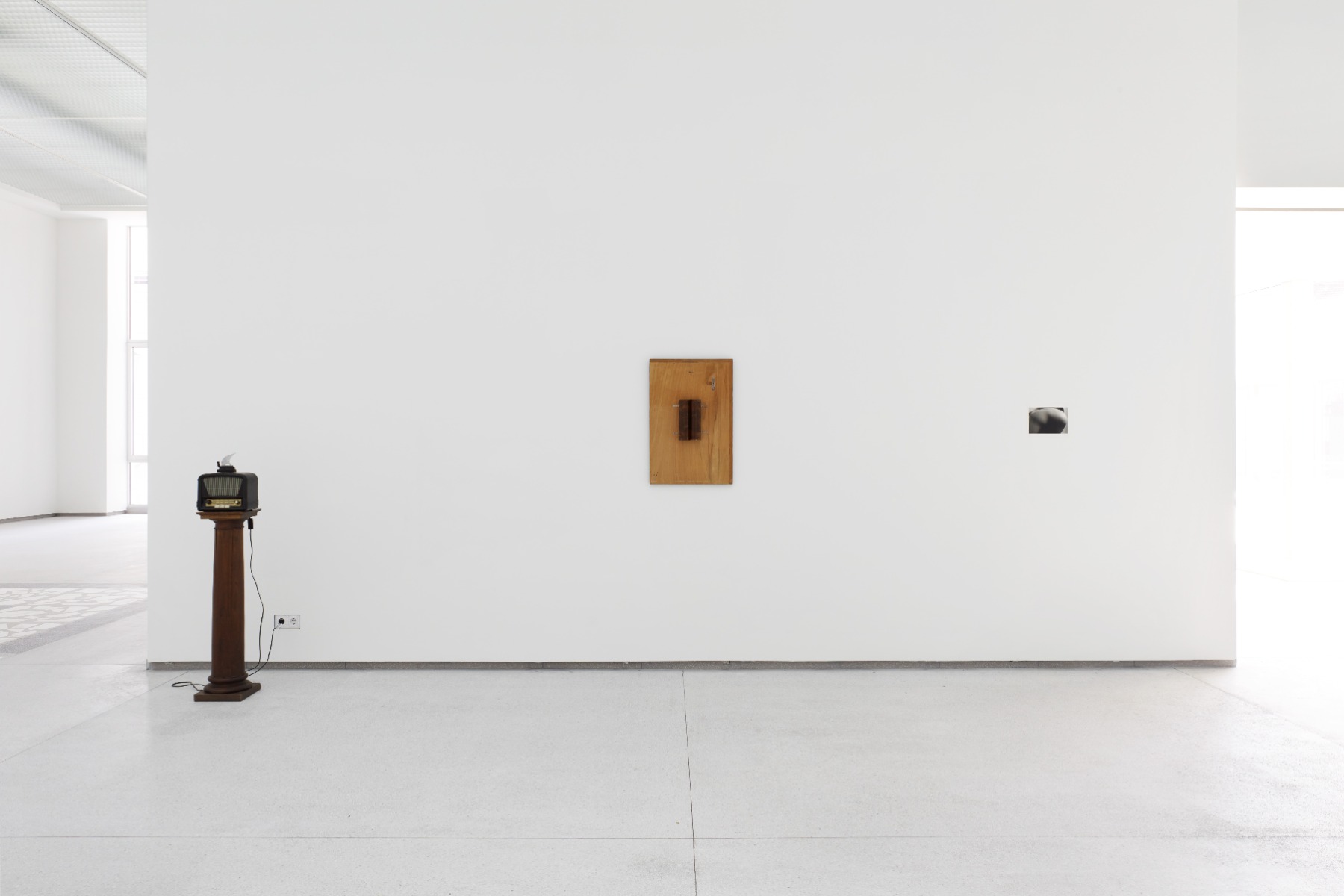

Kaarel Kurismaa, Vi king Radio”, 2001–2003. Read y-made, metal, plastic, elec tronics. Jiří Kovanda “Slip Away”, 1993. Wood, metal. I an Law, untitled, 2020. Fi bre based bromide print. Installation view,

Did you witness any examples of this in the 15th Baltic Triennial: Same Day curated by Tom Engels and Maya Tounta, currently on view at the CAC Vilnius?

I sense that Tom Engels’ and Maya Tounta’s triennial is somehow less overtly engaging with the politics behind writing a history of the Baltics. Nonetheless, the curators’ choice of pieces and method of display engage with the idea of contemporary time itself. Many works at the exhibition make use of analogue technology or obsolete technologies, which by their very nature, require a different kind of (eco)-labour, and condition a human body and artistic creativity in a certain way. More importantly, analogue language suggests enhanced attention to the materiality of time, and thus a possibility to slow it down via material disruption. It stands in contrast to accelerated global time and there is something nostalgic and slightly ideological about that. There is also an interest in lo-fi conceptual art tropes, and less material art practices and what they might offer is now as oversaturated viewers of images, information and things.

Exhibition halls in the CAC are left virtually unchanged, many pieces appear to be almost lost in the homogenizing white space. This way, it imposes a contemplative and slower viewing experience.

Josef Dabernig, L acrimosa,” 2024. 16mm film, digital transfer, black and white, sound. Installation view, 15th Baltic Triennial Same Day, Contemporary Art Centre (CAC) Vilnius, 2024. Photo: Kristien Daem

I agree with your observation that this triennial seems to connect its works around certain means of production and their intent to slow down the time. In particular, the attempt to go back in time or think about past time as the present is evident. I had this strange conviction that most works displayed on the Same Day were from the 80s and 90s. However, I flicked through the booklet, and I was wrong. Some works in the exhibition are indeed of historic neo-avantgarde, the ones by Kazimierz Bendkowski, Villu Jõgeva, Běla Kolářová, Ewa Partum, etc., however, most of them are created after the 2000s and quite a few created in the last years. Artists such as Ian Law or Bradley Kronz decisively follow in the footsteps of late avant-garde, other contemporary pieces probably appear historic because the curators decided to display them in a rather formal manner. Looking back on it I found the exhibition to be anachronistic or maybe questioning the idea of contemporary with anachronism.

What’s interesting about your analysis—or at least about pointing to an analysis of time, slowness, and production—is the idea of the contemporary as being, in a way, "out of time." It is diachronic, not fully tied to historical time, nor fully rooted in its own time. Somehow, it exists out of sync with what precedes it and has yet to align with what is to come. This notion of the contemporary as being out of sync with broader historical timelines, while simultaneously being of its immediate moment, suggests that it is not formed through historical dialecticism, historical materialism, or a Hegelian notion of forward evolution in time. When I think about it there is much to be explored in this area and this Baltic Triennial steers in that direction.

In a sense, this conception of the contemporary is itself becoming anachronistic. Given the sheer volume of wars and destruction in the world, alongside the accelerating erosion of democracy, it feels increasingly inadequate to frame the contemporary in traditional philosophical terms. This difficulty in grasping the contemporary is, I think, part of why it’s so challenging to understand the methodologies of fascism and the extreme right today. These movements are profoundly “out of time”, rooted not in continuity but in destruction, nihilism, misanthropy, and anti-humanism.

The scale of destruction they pursue is not just physical or institutional but temporal, aiming to dismantle human time itself. Compounding this is their deployment of advanced technologies— military, digital, and virtual—which render their strategies almost incomprehensible. This confluence of temporal dislocation and technological extremity makes it profoundly difficult to fully grasp or confront these forces in the present moment.

I don’t know—there’s something about it. I suppose what I’m saying is that my understanding of the contemporary is that it’s out of sync with historical time. Yet, because it’s so out of sync, it’s entirely of its present moment. It can’t be conceived as belonging to an earlier or later time because of its intrinsic relationship with the here, the now, and its sense of presentness. In art, this idea of the contemporary feels, at this moment, a bit out of sync with the world.

As for that exhibition, there’s something about it that seems to grasp at an earlier moment. It’s reaching for a time when being poetic, slow, scaled-down, minimal, and perhaps slightly abstract were seen as forms of political action or mobilization. But in this exhibition, I really felt the absence of a clear political agenda. I found myself missing the sense of purpose or direction to the point why is it important to look at the way art was thought to operate around 40 or 50 years ago. As I elaborated there are plenty of reasons why we would want to play around with ‘historic’ timelines now. A very concise curatorial statement in the Same Day just doesn’t cut it.

15th Baltic Triennial Same Day, installation view. Contemporary Art Centre (CAC) Vilnius, 2024. Photo: Kristien Daem

I appreciate your insight and thinking through the cracks in the chronology of time that are embodied by extremist political ideologies, the realities of wars, destruction, and death we experience today. To be honest, I haven’t thought of the Baltic Triennial in this context. Now that I do, the exhibition appears to be deeply nostalgic, I guess reminiscing positive things from the past is one of the ways to deal with the uncertain historicization of today. On the other hand, remembering the time when artists were more process- driven, experimental, and detached from the demands of the art market raises questions about whether this time ever existed. If it did where and when? We can talk about the welfare European state, and the strong democratic countries of the late 70s to early 2000s, where certain standards of life and strong state funding for art existed. In the interview given after the Prologue to the Baltic Triennial in 2023, curators Maya Tounta and Tom Engels express that instead of thinking thematically they curate the triennial with “intuitive methodology”1, which derives from their personal experience living in Vilnius (in Maya’s case) or working with Lithuanian artists (Tom’s case). The curators also emphasize that “we’ve both been informed by Lithuania over the years”, it is hard for me to assess but maybe the curators see the Lithuanian art scene—of the past and present—as this place where conceptual experiments in art still prevail, and the art market is not a defining force.

It is hard to argue against personal memories, intuition, and experiences, especially when the curators proposed they did not intend to create any argument or as Tom Engels says “aboutness” with this exhibition. However, I feel quite uncomfortable with the way the exhibition apparently celebrates artistic “freedom” outside the conditions of a liberal economy and simultaneously includes works created under state communism. I felt the lack of sociological and anthropological reflection and kept asking myself a question if the curators hold any responsibility to conceal the context of the works they exhibit? When does it become irrelevant and why?

I have three key reflections to share. First, I want to emphasize a positive aspect of the toning down on the contextual information at the exhibition: the air, or space between the works, the absence of overtly didactic material, and the way the architecture and natural light were emphasized. The building itself seemed to be the star, creating an environment that invited contemplation and a different kind of engagement with the art. The human-scale nature of the works and their restrained use of technology further contributed to a sense of subtlety, contrasting with the overwhelming presence of the space itself.

However, the problematic film by Joseph Dabernig in the basement stood out. It dominated the initial experience with a Western-centric, personal forms of storytelling approach situated in historical post-war identification and felt disconnected from the broader context of suffering, such as the sheer destruction of lives and lived space in Palestine and Lebanon. This work seemed misaligned with the gentler, more analytical concerns of the other pieces, and its placement made it difficult to engage with the rest of the exhibition.

Rey Akdogan,“Slit Drapes #2”, 2024. Tinsel. Tom Burr, “Dark Grey Matter”, 2011. Wool blankets and steel tacks on plywood

I want to address the issue of curatorial reflexivity. While the exhibition avoided imposing explicit meanings, this approach sometimes felt like a denial of the inherent relationships and narratives within the works. Curators, as mediators, bear responsibility for enabling connections and articulating ideas. When these connections were unclear, the experience became frustrating, and viewers were left to construct meaning independently. While open-endedness can be enriching, here it sometimes bordered on hermeticism, creating a disconnect from the immediate realities of the world.

Finally, the exhibition's broader context felt somewhat out of sync. Its aesthetic choices and conceptual approach evoked curatorial trends of the 1990s and 2000s, where works were juxtaposed like a “cabinet of curiosities”, often guided by a literary sensibility. This approach, though nostalgic, seemed detached from the contemporary moment and the specificities of the region. While the airiness and openness of the exhibition had an undeniable appeal, its investment in abstraction left me wanting more clarity and resonance with present-day concerns.

While the exhibition had moments of generosity and invited thoughtful engagement, it ultimately struggled to connect meaningfully with its context and audience. Its reliance on abstraction and aestheticized nostalgia, rather than a clear dialogue with the world, left it feeling disjointed and ungrounded. This may also have been its very point.

1 “Elusive Fissures. Virginija Januškevičiūtė in Conversation with the Curators of the 15th Baltic Triennial – Tom Engels and Maya Tounta”, CAC website, 16th May 2024. Accessed 25th November 2024. https://cac.lt/en/elusive-fissures-virginija-januskeviciute-in-conversation-with-the-curators-of-the-15th- baltic-triennial-tom-engels-and-maya-tounta/

The 15th Baltic Triennial was on view at CAC Vilnius from 06.09.2024 till 12.01.2025

Title image: 15th Baltic Triennial Same Day, installation view. Contemporary Art Centre (CAC) Vilnius, 2024. Photo: Kristien Daem