Where the Landscape Frames the Art

An interview with Bera Nordal, Director of The Nordic Watercolour Museum

Perched at the water’s edge in Skärhamn, on the picturesque island of Tjörn – afectionatelly called the “Island of Art” – The Nordic Watercolour Museum offers an unparalleled cultural escape. Just an hour north of Göteborg, this remarkable institution, set against a backdrop of naked cliffs and endless sea, is the only museum in Europe solely dedicated to watercolor painting. Yet, it is far more than an exhibition space – it is a hub for artistic research, education, and exploration of the watercolor medium’s infinite possibilities.

For nearly 25 years, the museum has celebrated watercolor’s extraordinary versatility, hosting exhibitions that span traditional techniques and groundbreaking modern interpretations.

The Nordic Watercolour Museum. Photo: Per Pixel![]()

At the Nordic Watercolour Museum, nature is not just a backdrop – it’s part of the experience. The architecture, named Mötet (“The Meeting”) by Danish architects Niels Bruun and Henrik Corfitsen, mirrors its philosophy of harmony between art, nature and community.

The breathtaking sea stretches before you, with smooth cliffs framing the view just outside the entrance. Inside, art and nature converge seamlessly, creating a tranquil and inspiring atmosphere. Across the bay lies Bockholmen, home to five minimalist guest studios perched on concrete stilts. Linked to the museum by a slender wooden bridge, these studios embody the balanced fusion of art, nature, and community, inviting artists to create while surrounded by the raw beauty of the island.

Guest Studios. Courtesy of the The Nordic Watercolour Museum

As the museum approaches its 25th anniversary, Arterritory sat down with its pioneering director, Bera Nordal. An Icelandic-born art historian and author with an impressive career, including director seat of the Iceland Art Museum (1987–1997), Malmö Konsthall (1997–2002), and The Nordic Watercolour Museum since 2002. Under her guidance, the museum has broken down watercolor into its elemental components – water, pigment, and paper – exploring it through the lenses of tradition, expression, and concept. By pushing boundaries, The Nordic Watercolour Museum offers a thought-provoking journey through watercolor’s history and its dynamic place in contemporary art.

The Nordic Watercolour Museum. Photo: Per Pixel![]()

The museum’s surroundings are nothing short of extraordinary – it's the kind of place where I feel my soul would reside, if it were outside of me. Is there anything that still gives you that sense of awe every time you return to the museum?

Oh, absolutely. Just recently returned from a trip, arriving at the museum late in the evening. It was already dark, but as I approached, I could hear the rhythmic sound of the sea. I thought, What a magical place this is.

When I first arrived here as museum director in 2002, it was also winter. The surroundings were unfamiliar, and I vividly recall the darkness and fierce wind. Yet, there was something exhilarating about it – a unique harmony between nature and the museum’s architecture. That feeling has stayed with me. It’s rare to find a place that integrates culture and nature so seamlessly.

Visitors feel this connection immediately. Whether it’s the light streaming through the windows or the sound of waves outside, there’s an indescribable serenity that resonates with all their senses. The museum itself provides an open, neutral space with high ceilings – a perfect setting to engage with art, connect with others, or simply be at one with nature. This indoor-outdoor connection is one of the museum’s most treasured features.

Exhibition by René Magritte "Laboratory of Ideas" / Le Séducteur 1952 © Stockholm 2022. Courtesy of the The Nordic Watercolour Museum

What has been the most rewarding aspect of directing a museum dedicated to the watercolor medium?

The Nordic Watercolor Museum is truly unique in the art world. It’s rewarding to demonstrate what watercolor can do.

While our collection is still growing, we prioritize building meaningful relationships with the artists whose works we acquire. It’s not just about owning an artwork – it’s about fostering a deeper connection so we can comprehensively present their art.

Although I’m not an artist, curating exhibitions is my form of creativity. Transforming the same space into something entirely new each time is incredibly rewarding. Sometimes, artists arrive with a clear vision, and my role is to help them realize it. Other times, they entrust us entirely with the design. Occasionally, we consult technical specialists for specific solutions because collaboration with experts is crucial. Each project brings unique challenges. What looks perfect on paper doesn’t always work in reality, and adaptability is key.

We aim to create most of our exhibitions in-house, which makes the process more personal and engaging for the whole team. It becomes a collective effort, and that’s incredibly fulfilling.

How does it feel when an exhibition ends?

It’s always bittersweet. Like after a celebration has ended, knowing you’ll never experience it the same way again. But it’s also exciting to start fresh and create something entirely new. Maintaining variety in the exhibition program is essential – you can’t follow one show with another too similar in theme or tone. That would feel monotonous and not meeting our goals.

Recently, you delivered a talk on ‘Museum Futures’. What are some of the key challenges museums are facing today?

Museums face significant challenges today. Iconic institutions like the Louvre or the British Museum attract masses eager to say they’ve been there. But getting visitors to truly engage with an exhibition is much harder than it used to be. This reflects something about our times – or expectations of what a museum visit should entail. You can’t just put a title on the wall, announce the exhibition, and say: Good luck! And see you next time! Museums today need to be proactive – engaging with audiences on social media, clearly communicating their mission, and offering educational programs and added value to enrich the experience. The landscape of art itself is constantly evolving. In the 18th century, creating a landscape painting was a groundbreaking moment in art, especially outside the traditional church or court commissions. However, today, it’s harder for younger generations to connect with such works – those endless rooms filled with landscapes in golden frames. Even through much of the 20th century, access to art was limited. The internet was a late arrival, and people primarily visited exhibitions or attended concerts in person. Today, we can access and experience art from anywhere, at any time. To stay relevant, art must be recontextualized for modern audiences. Art should still be experienced in person, except when it’s designed specifically for digital viewing.

Photo Courtesy of the The Nordic Watercolour Museum

Where does The Nordic Watercolour Museum stand in today’s world, as a relatively young institution?

We’ve worked hard to make this space inviting and accessible. Communication with the public is key for us, especially since we’re located on a remote island by the sea, far from major cities. Visitors put in the effort to reach us, so we ensure their experience is worthwhile – offering high-quality exhibitions, a fantastic restaurant, a cozy coffee shop, a unique gift shop, and educational programs for children. And, if the weather allows, you can even enjoy a swim nearby. Smaller museums often face the challenge of being perceived as elitist or intimidating, and breaking down that barrier is an ongoing priority for us.

Exhibition view. Jongsuk Yoon, "Wall Paintings", 2020. The artist in front of her work at the Nordic Watercolor Museum. Photo: Kalle Sanner

Watercolour is often seen as a casual or hobbyist medium. How do you view its significance?

Unfortunately, there’s a common perception that watercolor is a less serious medium. However, when you dive deeper, it reveals an incredible depth and versatility. Artists like Albrecht Dürer used watercolor for intricate studies and exquisite manuscript illustrations.

This summer, Norway’s National Museum held a major survey of Mark Rothko’s works on paper. The pieces were stunning and rarely seen, mainly because most museums are designed to showcase large-scale paintings, sculptures, or installations – rarely paper-based art. It’s a bit paradoxical, really.

At The Nordic Watercolour Museum, we showcase the medium’s diversity and provide a safe space to exhibit these often fragile works.

Watercolor is accessible – requiring just pigment, water, and a surface (often paper). It can be approached in classical ways or reimagined through conceptual techniques, exploring the dynamic interplay between water, pigment, and paper. The results can range from delicate washes to bold, expressive strokes.

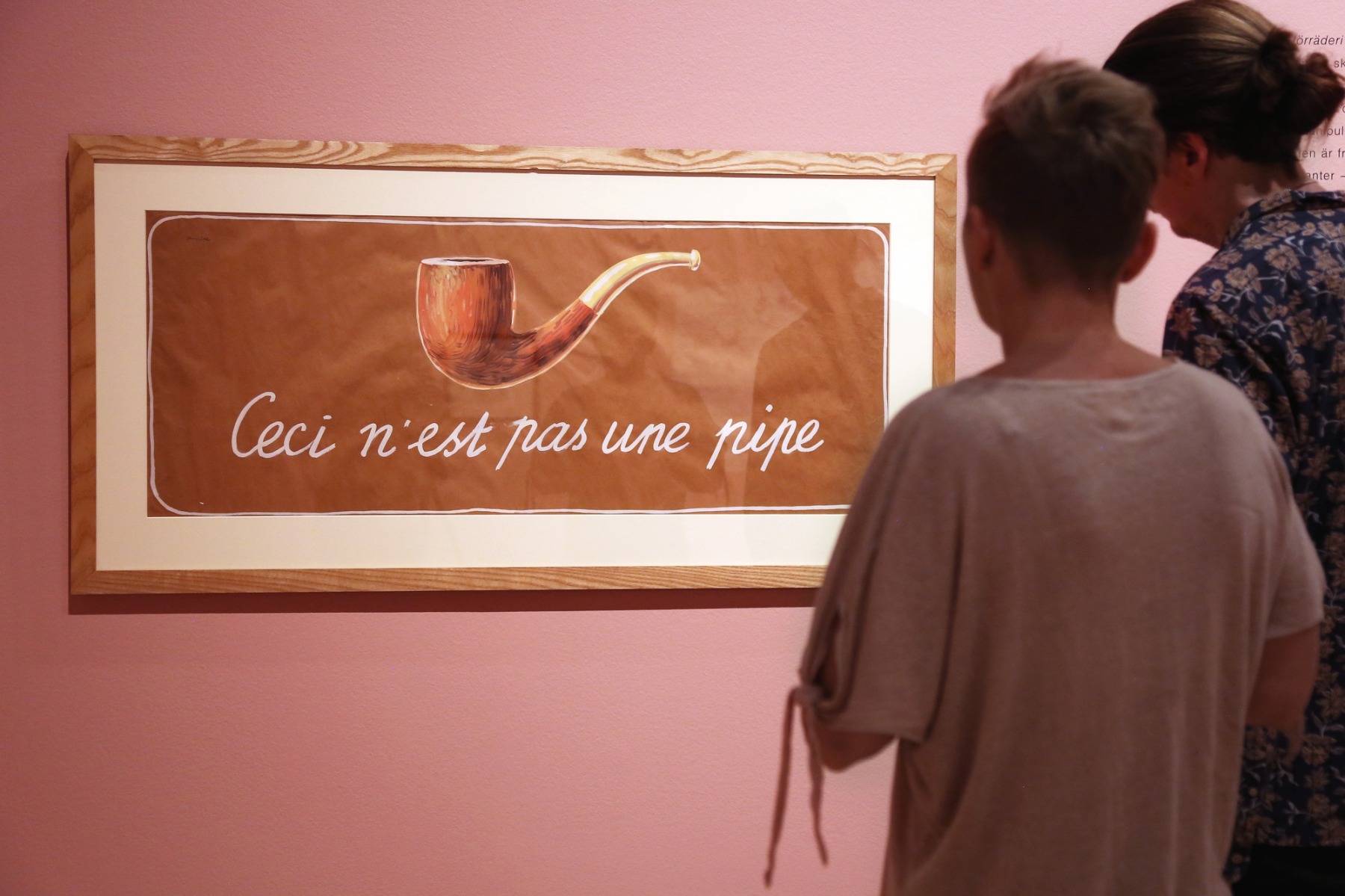

Exhibition by René Magritte "Laboratory of Ideas" / Poster for a shop window, 1952 © Stockholm 2022

Exhibition by René Magritte "Laboratory of Ideas" / L'homme et la forêt, ca 1965 © Stockholm 2022. Courtesy of the The Nordic Watercolour Museum

If you were to illustrate the history of works with watercolor, which artists would you include?

Subjectively, I would begin with Maria Sibylle Merian’s botanical illustrations, which highlight watercolor’s historical role in bridging art and science. Albrecht Dürer would naturally follow, as his precise and intricate works laid the groundwork for later developments in the medium. Moving forward, I’d include René Magritte’s wash and gouache paintings, which he often used to refine his ideas before translating them into oil paintings – his extensive watercolor works were featured at The Nordic Watercolour Museum in 2022. Alice Neel’s watercolor portraits also stand out for their strikingly contemporary quality. Finally, Andrew Wyeth’s mastery of the dry-on-dry technique offers a sharp contrast to the looser, more expressive styles of Bernd Koberling.

Christine Ödlund. Botanical Thought-Form II, 2024, Botanical Thought-Form I, 2024, Världsträdet, 2024. Courtesy of the artist & CFHILL. Photo: Kalle Sanner

Which contemporary artists stand out for their storytelling through watercolour?

Hans Op de Beeck comes to mind. His large-scale works, in deep gray tones, evoke cinematic landscapes and moments of nostalgia or imagination.

Another is Christine Ödlund, whose art explores plant communication and draws inspiration from early scientific illustrations. Her work connects sound, image, nature, and culture. Her current exhibition, This Garden and Its Spirits, is on view at The Nordic Watercolour Museum and exemplifies the medium’s conceptual potential.

These two artists boldly demonstrate how watercolour remains a relevant and dynamic medium.

Christine Ödlund, Four Dimensions of a Swamp, 2023. Courtesy of the Firestorm Foundation

Can you share insights about Christine Ödlund’s work? It sounds intriguing.

Christine Ödlund’s work is captivating, blending late 19th- and early 20th-century modernism with spiritualism, drawing inspiration from figures like Hilma af Klint. A distinctive aspect of her practice is her collaboration with scientists to study plant behavior – plants can communicate with each other in response to insects or environmental changes. Christine visualizes these hidden systems in her art, often incorporating her background in music to create intricate compositions.

Exhibition view. Christine Ödlund. This Garden and its Spirits. Photo courtesy The Nordic Watercolor Museum

Her work evokes the botanical illustrations of early natural science, recalling Maria Sibylla Merian, the renowned 17th- and 18th-century entomologist and illustrator. Merian meticulously documented plants and insects long before photography, underscoring how essential artists were to scientific progress. Historical figures like Merian and Swedish biologist Carl Linnaeus, while not traditionally considered artists, were exceptional draftsmen, trained in drawing and watercolor to document the natural world. Their visual records helped scientists categorize and understand nature with greater precision.

Christine Ödlund continues this legacy, blending artistic insight with scientific exploration to uncover the hidden connections within nature.

Exhibition view. Christine Ödlund. This Garden and its Spirits. Photo courtesy The Nordic Watercolor Museum

Where and/or when do you feel closest to nature?

Growing up in Iceland, I’ve always felt deeply connected to the sea. It’s a source of energy and a space for reflection. I love long walks – they clear my mind. Spending time alone is vital for me. After giving so much of myself to the museum and its visitors, solitude helps me recharge. I’m also an avid reader and naturally curious about many topics, from art to technology. Recently, I’ve been particularly interested in artificial intelligence, but that is very far from the natural world.

Exhibition view. Christine Ödlund. This Garden and its Spirits. Photo: Kalle Sanner

In your words, what makes water, the sea, and the ocean such a universal and timeless subject in art?

Water is a profound metaphor for life itself. Think of a young child – their body is full of water, vibrant with life. When my father passed away at 99, he looked as though he had dried up. His cells no longer renewed as they once did, but he aged beautifully. Water symbolizes vitality, change, and resilience.

That’s a moving comparison. Thank you for expressing it so beautifully. Sometimes, a gift you can give someone is a beautiful new thought.

What parallels can you draw between water’s ability to shape landscapes and art’s power to shape human thought and culture?

Water is a powerful force of nature. Growing up by the Atlantic Ocean, I saw how the sea could be both mesmerizing and terrifying. Water has always connected humanity, driving exploration and discovery. For centuries, people have ventured beyond their borders seeking something greater. The Norwegians who settled in Iceland in the ninth century, for example, brought their culture. Similarly, just as a stream smooths a stone over time, creativity shapes society. Art, as a profound expression of culture, influences and transforms civilization. While some cultural expressions may gain more prominence, who can truly determine which holds greater value? The Vikings, for instance, traveled from the North to as far as Istanbul and Yemen – just as art connects people, serving as a universal language to explore differences and celebrate commonalities.

Cultural conflicts are likely to emerge.

Yes, undeniably. However, when you explore cultures in depth, you begin to notice profound similarities at their core. These similarities – like rivers – have a way of connecting people, even when they diverge and flow in different directions before meeting again. It’s a beautiful metaphor for human interaction and cultural exchange.

Exhibition "Animal Kingdom", 2023. Courtesy of the The Nordic Watercolour Museum

I’ve noticed that Icelanders emphasize how people across nations and continents are more alike than different. Why do you think this perspective is so strong in a small nation like Iceland?

Hah, interesting. I believe it stems from our deep connection to nature and spirituality. While the church plays a role in Icelandic life, our spirituality is uniquely rooted in nature. We hold our myths dear – tales of trolls and elves that might seem naive or even absurd to others, but carry an inherent beauty. For instance, my grandfather used to say that if he lost something, it was because the elves had taken it – and that they would eventually return it. Coming from Iceland, I find the Japanese reverence for nature very relatable. We share a lot of similarities, perhaps due to our shared experiences with geology – hot springs, earthquakes, and volcanoes. Both cultures live alongside nature’s raw energy and recognize that failing to respect it comes at great peril.

I believe, that in 2018, The Nordic Watercolour Museum presented the exhibition Japan – Spirits of Nature touching these subjects.

The exhibition explored the parallels between Japanese and Scandinavian cultures, highlighting their shared appreciation for design and spiritual bond with nature. Both cultures have long used myths to explain natural phenomena. These ancient stories continue to resonate in Japanese contemporary art. While the mediums of expression may differ, the core idea remains the same: the interconnectedness of all things.

Walton Ford, La Madre, 2017. Courtesy the artist, Galerie Max Hetzler, Berlin, Paris, London

Humans are part of nature, not separate from it. Yet, driven by a fear of mortality, we often act selfishly, taking from the environment and life with the mindset that ‘we live only once’. Take and discard, take and discard and move on.

Yes, exactly. We are part of a much larger whole, a greater picture. Every action we take has far-reaching consequences, often beyond our immediate environment. Accepting the inevitability of death can help shift our focus towards the needs of future generations – those we may never meet. If we stop seeing ourselves as the center of everything, we might finally be able to do good.