There are many Amazons, coexisting at the same time

An interview with Claudi Carreras, cultural producer, photography researcher and curator of the exhibition Amazons. The Ancestral Future at the CCCB arts centre in Barcelona

The exhibition Amazons. The Ancestral Future, on show until May 4th at the CCCB arts centre in Barcelona, is one of the most powerful stories ever told about the Amazon region. It neither idealises nor romanticises the Amazon as we’ve seen in recent years, the main instigators of which being ayahuasca tourism and the focus being put on indigenous art by the Western institutional art scene, the latter failing to categorise it according to its own measures and ideals since the context and aims of indigenous art are often completely different. Nor does the exhibition dramatise or fatalise the Amazon, although it does shed a stark light on what rainforest destruction, fires, industrial cattle ranching, the struggle for resources, and the greed of global conglomerates have done and continue to do to the world’s largest tropical ecosystem, and thereby, to the planet as a whole.

The exhibition makes us think about the constructs we build in our minds and accept as truth – in this case, the constructs ‘rainforest’ and ‘the Amazon’. As the plural title of the exhibition, Amazons, suggests, there is no such thing as one Amazon. Amazonia is vast in its extension and diversity: it takes in nine countries (Brazil, Bolivia, Peru, Ecuador, Colombia, Venezuela, Suriname, Guyana and French Guyana) where over 30 million people live, 60% of them in urban areas. The region is twice the size of the area encompassed by the European Union. And, perhaps consciously or unconsciously, in the dualistic divide between ‘us’ and ‘them’ which, despite flashy decolonisation efforts, still exists in our minds, one of our greatest challenges is to respect the Amazon for what it is. We must accept what is different and distinct, and understand what we can learn from this. It is not an easy exercise, yet it is very enlightening when we recognise that the same lessons can just as easily be applied to any other geographic area surrounded by (Western) stereotypes and stigmas.

The Amazon region is home to more than 400 indigenous peoples who speak more than 300 different languages. Some of them still choose to remain completely isolated and avoid all contact with the so-called civilised world. They are aware that for them, this is also very much a question of survival and preserving their identity. The indigenous communities have survived without severing their connection with nature, their roots, their ancestors, and their ancestral knowledge. It is a unique web formed by the interaction of nature and cultures, and one in which there is a completely different understanding of time and so-called progress. For the peoples of the Amazon, the concept of memory is not an abstraction of the evidence of the past; instead, it embodies a continuum of experience and knowledge in which there are no strict divisions between past, present and future, but a continuous cyclicality in which everything is interconnected and every action triggers a chain of causal relationships.

As recent archaeological discoveries show, the region has been inhabited by humans for at least 13 000 years, and ancient Amazonian civilisations developed unique technologies for plant cultivation and food storage, their own architectural traditions, and a symbiotic relationship with the rainforest. They were highly developed long before the arrival of missionaries and the ‘rubber barons’.

The exhibition has been four years in the making, during which time its curator, Claudi Carreras, and the creative team have travelled 6 900 kilometres throughout the Amazon. They interviewed more than 300 people – indigenous community leaders, artists, farmers, scientists, etc. – thereby giving a voice to the indigenous people of this region – people who are tired of being ‘objects of study’ and ‘exotica’ to others. It is no coincidence that one of the central elements of the exhibition is the maloca, a space of conversation and ritual specially constructed according to ancient knowledge. Every community has one, and it serves as the heart of its intellectual and social life. A place where words and knowledge are honoured because words, like art, are very important to indigenous cultures – it is words that have made it possible to tell stories that are still passed down from generation to generation. Of course, sacred plants are also an integral part of Amazonian cultures, and it should be noted that the Western habit of highlighting them and taking them out of their specific context – to the point of disrespecting them and using them casually and carelessly – is also a kind of colonialism. Dreams and hallucinogenic plants have played a crucial role in indigenous cultures – through them they have have communicated with their ancestors, the great forest and its spirits, as well as received knowledge in an indirect way that helps them find the best solutions for their own survival and well-being. The exhibition offers a glimpse into different realities through sound, colour, smells, paintings, drawings, photography, and video installations, making them distinctly present while also making us think about how inclusively, openly and responsibly we each build our own reality.

The exhibition is also a unique opportunity to enjoy new work that has been specially commissioned from outstanding artists and indigenous groups, like the impressive murals painted on site at CCCB by the Mahku Collective (Huni Kuin, Brazil), Elías Mamallacta (Kichwa, Ecuador), Olinda Silvano and Cordelia Sánchez (Shipibo-Conibo, Peru), and Rember Yahuarcani (Uitoto, Peru); photographs and audiovisual montages by Andrés Cardona; and the artistic installation by Nereyda López and Santiago Yahuarcani (Uitoto, Peru).

Colectivo Água (Pablo Albarenga, Mariana Greif, Soll Sousa) with the collaboration of Raimundo “Berro Grosso,” Memorias del río, 2023. Drawing on printed digital photography. Courtesy of the artists

As Claudi Carreras said during our conversation: ‘I’m trying to create an immersive space to reflect on how we are losing our connection with nature, and to consider that there are other communities that still maintain this connection – perhaps we can learn from them. I want to show how we are drifting away from nature and how we need to rethink and relearn our relationship with it.’

With a degree in Fine Arts from the University of Barcelona, Carreras is an independent curator, editor, cultural producer, and photography researcher. As a curator, he has curated multiple exhibitions that have been shown in more than fifty countries, including Laberinto de Miradas, Cotidiano Latino, ECO, Africamericanos, and Inside the Curve (NGS).

He has curated the Paraty em Foco festival in Brazil, where he participated from 2011 to 2015, as well as the selection from Latin America at the Photoquai Biennial held by the Musée du quai Branly in Paris in 2013 and 2015. He was an advisor and curator of the Latin American Forum of Photography in São Paulo since its creation in 2007 until 2019. He has been a jury member of important competitions such as the World Press Photo Contest, POY Latam, the Sony World Photography Awards, and Spain’s National Photography Award.

Carreras is currently the founding director of the VIST Foundation and advisor to the National Geographic Society’s Storytellers Collective in Washington.

©andrés cardona / VIST

For me, it was interesting to discover that the title of the exhibition uses the word ‘Amazons’ instead of ‘Amazon’, emphasizing the plural form. People often think of the Amazon as a vast rainforest without knowing much about it. They tend to see it as a whole, recognizing its immense size, but in reality, it is a completely independent and ancient ecosystem.

Additionally, on Netflix, there is a series called Ancient Apocalypse, which, if I remember correctly, ends with an episode dedicated to the Amazon. It presents the idea that the Amazon was actually cultivated as a garden. I believe this is exactly what you are trying to convey through this exhibition – that the Amazon is something entirely different from the stereotype we Westerners tend to have.

I think you’re absolutely right. Everything you’re talking about – the Amazon – is impossible to reduce to a single concept. That’s why we refer to Amazons in terms of vastly different aspects, not just because it is a vast land with many ecosystems. The Amazon begins in the Andes at an altitude of 6,000 meters, with glaciers and freshwater rivers. Within the Amazon, you can find deserts, rainforests, and many different types of forests. It is an immense region, home to more than 400 distinct indigenous cultures, which have also mixed with cultures from all over the world.

The indigenous population makes up roughly 10% of the total population of the Amazon. Within that 10%, there are 400 different communities living in diverse environments and following different ways of life, speaking around 300 languages. The Amazon spans nine countries, making it the largest rainforest in the world. This vast complexity is why we talk about Amazons – because there is not just one Amazon, nor a single way to define it.

For me, the most important aspect of the exhibition is not simply to talk about the Amazon itself. Rather, it is about how the cultures represented in the exhibition experience their relationship with nature. If you ask a child in Barcelona to draw nature, they will likely sketch trees, animals, and mountains. However, if you ask the same question to an indigenous person from the Amazon, their perspective is entirely different – they see themselves as part of nature. For them, nature is not something separate from their existence. This deep connection makes their worldview incredibly complex, and for me, that was the fundamental guiding structure of the exhibition.

The rainforest was obviously shaped by human populations, but not only by humans. For indigenous peoples, everything is interconnected – the ecosystems, their conversations with plants, animals, and even spirits. Their mental and spiritual ecosystems are incredible because they maintain a deep, holistic connection with everything around them. That is the starting point of the exhibition: we cannot speak of a single Amazon. There are many Amazons, coexisting at the same time.

At the same time, we must recognize the impact of human populations in shaping the forest. This influence has existed from the very beginning. The Amazon is, in many ways, like a vast garden, created over time by humans, animals, and all forms of life that have shaped it. For me, this perspective is revolutionary because it challenges the way we traditionally think about tropical forests.

In English, the term virgin forest is often used, but in Spanish, the term selva virgen carries connotations of something untouched – something that can be conquered or violated. This colonial mindset assumes that if a forest is virgin, it is empty and available for exploitation. But this is far from the truth. The Amazon has never been a virgin or uninhabited forest. It has always been a populated, dynamic environment with incredibly complex relationships between humans and nature. Understanding this changes everything – it reveals a deep, symbiotic connection that has existed for thousands of years. They truly understand how to create strategies for survival and how to learn from nature. They can listen to nature. Meanwhile, we lost this connection long ago. That’s why we need to pause, reflect, and relearn. We must ask ourselves: how did we lose our connection with nature? How did we come to believe that we are separate from it?

This way of thinking has led us to treat nature as something we can exploit without consequence. But if we recognize that we are part of nature, then we must fundamentally change our entire way of thinking about life.

©andrés cardona / VIST

It’s also very interesting that there is a common stereotype that the soil in the Amazon region is very poor. However, in reality, it regenerates very quickly, especially around settlements where people have lived. In a way, parts of the Amazon forest have actually been cultivated. Many of the plants we use in our food today originate from the Amazon. This is yet another piece of knowledge that we have forgotten.

The first chapter of the exhibition is titled “The Message of the Roots”. Here, we focus on the archaeological aspect, featuring the work of Eduardo Neves, a Brazilian anthropologist and one of the leading researchers in this field. He studies how the forest was populated by indigenous communities and how they developed agriculture. For example, the Amazon is one of the earliest regions in the world where agriculture emerged. Many plants domesticated by indigenous communities are still in use today.

These communities have a complex relationship with nature. They didn’t build large structures because they were deeply integrated with ecosystems. While we don’t have many archaeological ruins from their time, we do have countless artifacts, as they used different materials to preserve the forest.

Another important concept is the black lands of the indigenous people – I’m not sure if you’re familiar with this term, but it refers to the fact that indigenous communities created fertile land for agriculture within the forest. This land is ideal for planting useful food, demonstrating their deep understanding of sustainable farming.

The first part of the exhibition features the installation of Jõao Paulo Lima Barreto, an indigenous Tucano anthropologist and researcher. Titled “Cosmologies and Cosmovisions”, it explores the construction of the world from the perspective of indigenous cultures, presenting a chronology of creation as understood by these communities. Through Barreto’s work, visitors embark on a journey into the ancestral knowledge of the Amazon, listening to more than 55 voices within the maloca.

©andrés cardona / VIST

The maloca – a traditional indigenous communal house – was built specifically for this exhibition. All the materials were sourced from Colombia, and over the course of 15 days, more than 10 indigenous people worked together to construct it. The maloquero, the indigenous leader responsible for building the maloca, traveled to Barcelona to oversee its creation.

The day before the exhibition opened, he performed a ceremony to inaugurate the maloca and formally present it. He declared, Now you have a spiritual house from the Amazon here in Barcelona. Now it is your responsibility.This is not just a decorative installation – it is an authentic maloca, built by an indigenous leader with deep knowledge of its significance.

Eighty-five percent of the population in the Amazon lives in cities. There are large cities like Manaus, Iquitos, Leticia, Belem do Parà and Rio Branco. These cities are closely connected to the forest, and many indigenous communities come to the cities to trade, exchange goods, and share their spiritual practices. It’s fascinating to think about how cities in the Amazon are structured today, not just the forest or the tropical nature. These cities are deeply intertwined with colonialism, extractivism, and the economic movements of urban life.

The second part of the exhibition addresses how the cities in the Amazon function and how they are represented. In this section, more than 20 different artists contribute their visual representations of the Amazon. These artists include African-American, European-descendant, and indigenous creators, all showcasing their unique perspectives on how they see themselves and their communities. This part of the exhibition emphasizes how the population of the Amazon is portrayed from the viewpoints of the people who live there.

The third part of the exhibition focuses on the processes of extractivism and the history of resource extraction in the Amazon. It begins with quinine, one of the first substances to drive the pharmaceutical industry in the region. The exhibition also covers the importance of rubber, which was a key commodity during the rubber boom, and the rise of agriculture, particularly soy cultivation.

Both legal and illegal mining have caused widespread destruction, while oil extraction has also played a significant role in this devastation. One powerful installation, created by Colombian filmmaker Andrés Cardona, features a representation of the burned forest. Visitors can see and even smell the charred remnants of the land. This installation underscores the devastating impact of extractivism and the ongoing connection between Europe, North America, and the Amazon.

Rember Yahuarcani. ©andrés cardona / VIST

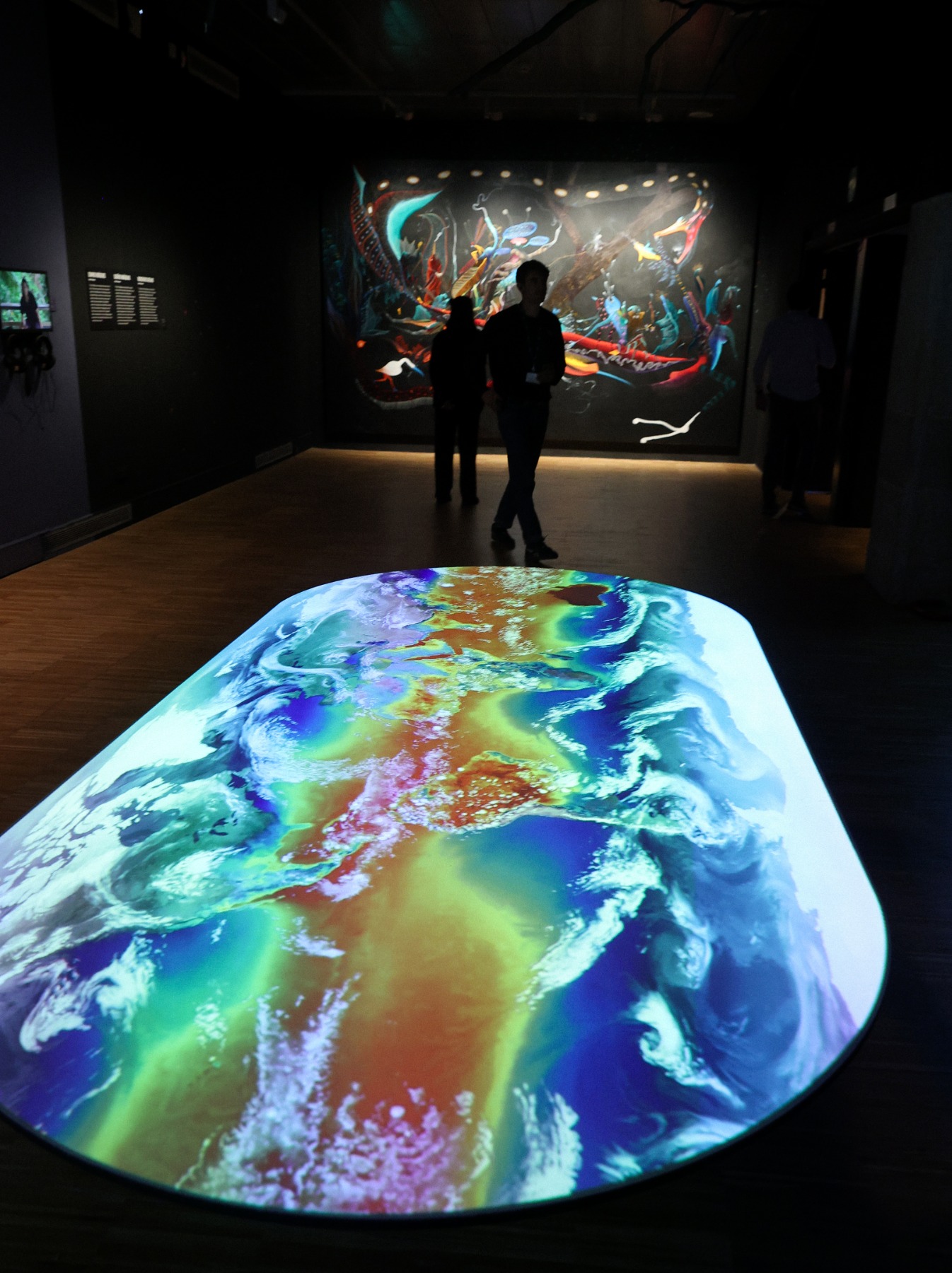

The final part of the exhibition feels like a dream. It explores the deep connection between fungi and plants, illustrating how micro-ecosystems are interwoven with the macro. Visitors can also view global maps that highlight the scientific and strategic significance of the Amazon. A key element of this section is the work of Rember Yahuarcani, an indigenous artist who was also featured in the main exhibition at the last Venice Biennale.

In this exhibition, we showcase a mural created by him, which represents a vision of the future of the Amazon. This is the concluding section of the exhibit, focusing on the theme of interconnectedness. The title of this part is We Are a Fabric, and it highlights how we can nurture these connections. It emphasizes that while everything that happens in the world is significant, the Amazon is essential for the well-being of our global ecosystem.

How long did it take to put the exhibition together? I imagine it involved many travels and was a tremendous amount of work. It really seems like a huge undertaking.

The entire process started four years ago, but for the past two years, I’ve been traveling throughout the Amazon. I interviewed more than 300 people in the region to prepare for the exhibition and traveled across all the rivers by boat. I spent six months on this journey, starting in Ecuador, traveling by boat to Peru, then from Peru to Colombia. I crossed into Colombia and then into Brazil, covering a total of 6.900 kilometers and speaking with many different people along the way.

I’ve also traveled to other places like Acre and Bolivia. I was based in Brazil for five years, and I’ve known the Amazon for about 20 years. I have a foundation in Colombia, where we’ve been working with indigenous communities for more than seven years. Our projects focus on various aspects of life in the region, approaching them in different ways. Because of this, I’m very familiar with the Amazon’s population in many areas. But, yes, it has been an enormous undertaking.

©andrés cardona / VIST

I think it was a huge journey for you personally as well. You already knew the Amazon, of course, but spending two intensive years preparing the exhibition must have led to many discoveries for you as well.

My life changed. I’m not the same person who started the journey. It’s something deeper, more spiritual. I’m in my 50s now, and I decided to cross the equator because I felt the need to stop, reflect, and connect with different ways of understanding. It’s truly impressive because you can feel nature in a new way. You feel a deeper connection to life itself. For example, I never really thought about the importance of water in our world until I was in the Amazon. Everything there is water; we are water, and we’re connected to our ancestors through it. Water is everything to us, yet we often take it for granted, using it for things like flushing toilets. It’s staggering to realize how we pollute water, using it for so many harmful purposes when it’s such an essential part of life.

When you experience the Amazon firsthand – surrounded by mosquitoes, animals, and the constant risk of diseases like malaria – you realize that we don’t have control over everything. Our culture convinces us that we have control, that we are comfortable in our routines, moving from work to home without ever considering the outside world. But when you immerse yourself in a different environment, you feel your body in a new way. During this journey, I could really feel my body, and that was incredible. You realize just how connected you are to everything – the land, the air, the water – and we forget about that in our everyday lives.

This is why I feel it’s important to express this idea in the city: we are truly connected to our environment, and if we recognize that, we can begin to grow in harmony with it. As I mentioned earlier, it’s about changing our paradigm. For me, this journey was a one-way trip. I’ll never be the same, because it gave me the time and space to truly think about things we often overlook.

Our idea was to cross the equator line by the river, which took about a month of traveling by boat. Of course, it wasn’t a direct journey – it wasn’t a straight path, as we stopped at many points along the way. We spent several days on the river, in the boat, thinking, watching the water, observing the rain, and crossing the river. During all those days, you reflect on things, and that experience was a major turning point for me. For me, the exhibition is a reproduction of this journey. And I didn’t do it alone. I traveled with Andrés Cardona, a videomaker, and Joseph Zárate, a journalist. For us, it was a one-way trip. We are still in the Amazon.

'Amazons. The Ancestral Future’ Installation image, 2024 / CC BY-SA-NC Martí Berenguer. Courtesy of CCCB Barcelona

If I understand correctly, you had a physical connection with nature – your body was connected to it, not just in your mind, but physically as well.

We took Ayahuasca several times and participated in cultural practices with indigenous communities at each stop. We spoke with them about our projects and often took part in ceremonies. The Ayahuasca ceremonies, in particular, have the power to shift your perspective, mindset, and much more. Through this experience, you become spiritually connected, and your body is fully immersed in the reality of the journey. There’s no other way to describe it.

Gê Viana, from the series 'Paridade' (2020). Primera capa: Neide Santos Cururupu, MA Photo; segona capa: dona guaycuru (Paraguai), 1843–1847. Photo montage. Courtesy of the artist

It’s fascinating how the indigenous people of the Amazon discovered how to combine these two completely different plants to create Ayahuasca. We still don’t know how they managed to figure this out, especially considering the vastness of the Amazon and the fact that the tribes lived so far apart from each other. It’s a mystery. Having traveled so much throughout the region, do you have your own thoughts on this? Of course, it remains a mystery, but it’s something I always wonder about – how did they discover this unique compound?

It’s not just Ayahuasca; they also use various other plants, like Yopo. These substances are used in unique ways, and it’s truly impressive how they can connect you to their world. I had a conversation in the north of Colombia, in Mocoa, Putumayo, where we held a workshop with 20 young indigenous people to discuss communication. On the last day, one of the young participants came up to us and said, “My grandfather wants to talk to you.” So, we went to the maloca to speak with the elder.

They asked me questions I had never thought about before – it was a surreal experience. They called me “teacher”, which took me by surprise. One of them said, “Teacher, you’re always talking about communication, but you really don’t understand indigenous communication”. They made me realize that communication for them is not the same as it is for us, the “white people”. They pointed out obvious things about communication that I had never considered. It was a moment of profound insight and a challenge to my own preconceived notions.

They then said, “We think we need to help you. If you’re going to talk about the Amazon, you must first experience our medicine. We will prepare it for you, as it is the key to connecting with and understanding the Amazon.” This was an incredible experience. They conducted a ceremony with three elders from the community to prepare me for speaking about the Amazon. It was unlike any journey I had experienced before. I felt as if I were constantly inside a bird’s egg, unable to break free. They told me I didn’t yet know anything about them and that I had so much to learn before I could truly speak about their culture. But through this struggle, I discovered many connections to different worlds, and they helped me understand various aspects of the journey from diverse perspectives.

Rember Yahuarcani, Aquells altres mons (díptic) (2024). Acrylic on canvas. Courtesy of the artist

I think we also do not know enough about indigenous art because, as the last Venice Biennale proved, from our Western point of view, we couldn’t fit it anywhere. It’s not in the Western system, and we are trying to look at it as outsiders and talk about decolonization and other things. But actually, it’s something totally different because it’s authentic, it’s pure. It existed years before our Western art was born, but we are still struggling with it. It was really interesting because, reading the reviews after the Venice Biennale, you can see that many people simply do not understand what to do with it and how to look at it. They also do not understand the spiritual aspect of it.

For sure, this is a really important point. I’m not working for the art market, nor am I legitimizing it at this time. The CCCB is not just an art space; it’s not like the Reina Sofia. In the context of the Venice Biennale, the situation is even more complex because the Biennale defines how art is perceived today and how contemporary art evolves.

The decision to include indigenous art in the market has sparked deep discussions within communities, and it’s incredibly challenging to find a balance. In some cases, like that of Rember Yahuarcani, he is a great artist who consciously chose to enter the art market. He studied for it, moved to Lima, understands the market’s rules, and navigates them skillfully.

But in other cases, it’s different. Some artists remain deeply embedded in their communities, and their artistic production is fundamentally communal. When this art is extracted and placed in a different context, it is often treated as individual art. By integrating indigenous art into the market under the contemporary art paradigm, we risk violating important cultural principles.

This is something we need to reflect on. It feels significant because it represents something new, but at the same time, I wonder if it’s just another trend – part of the art market’s constant renewal. Now, indigenous art is gaining attention, and while it is extraordinary and deeply meaningful, how this moment unfolds is critical to consider.

Ultimately, it represents a cultural divide. For indigenous communities, these artistic traditions are not merely “art” in the Western sense; they serve communal, spiritual, and cultural functions far beyond the commercial realm. Everything is intertwined because they aren’t artists in the traditional sense of the word. Of course, they are, but many different elements are being merged and redefined. That discussion, for me, is really important. But I don’t have definitive answers.

In this exhibition, we are not simply talking about art. We are talking about the Amazon and its ancestral connections, using art, science, visual discussions, and different languages. It’s a panoramic project with many layers and perspectives.

Lalo de Almeida, Protesta dels munduruku a Belo Monte (2013). Courtesy of the artist.

But it’s very interesting because indigenous art is showing us that art is part of the ecosystem. It’s an organic part. It’s not something separate, like a bubble. It’s a necessity for humans to communicate on a different level. There are no words in art; you can communicate through art about your feelings, your concepts, but on a totally different level. And I think art has also been so important in our human history because it’s essential for well-being, and indigenous people still have it integrated – it never stopped. They approach it in that way.

Absolutely, the problem is not the consideration of art. I think the friction arises when we talk about the art market, because it’s different. You have community art that has been created over thousands of years, rooted in oral traditions of storytelling and drawing. When you take someone from these communities and say, ‘Okay, you are an artist,’ it’s true that they are artists, but they are part of a different set of connections to the world. By doing this, you create many problems within that community. I think the disconnection isn’t in terms of the artists, but more in terms of the art market. It’s interesting, though, because the way the market relates to art requires this kind of inspiration, but when you include indigenous art in the market, you’re creating many discussions within the communities in the Amazon and the tropical forest.

'Amazons. The Ancestral Future’ Installation image, 2024 / CC BY-SA-NC Martí Berenguer. Courtesy of CCCB Barcelona

Yeah, it’s similar to what’s happened with Ayahuasca. We’ve taken it from indigenous knowledge and placed it into Western culture, and now it’s become a kind of hype. This commercialization has damaged the local ecosystem in the Amazon as well. We’re constantly trying to extract something and turn it into a fashion trend, but we don’t consider the deeper layers of this tradition – how it was used, what the set and setting were, and how important it is to have knowledge of how to work with it and where to use it. It’s a huge problem because we try to commercialize everything.

You’re hitting the most important point. Culture can create connections and communication with other cultures, and we need to engage in discussions on the same level. But we always seem to fall into the trap of creating extractivist processes. The colonial times are over, but we still struggle to really change. While we talk about it, we often fail to act. We need to be aware of whether we are truly engaging with other communities at the same level or if we are still using them as we always have. This is the huge discussion. The new moment for indigenous art could open our minds and reconnect us to other aspects of life, but we also have to be careful that we are not using it in the same extractivist way as always. So the question is: Are we prepared to engage with other cultures on an equal level, or are we still using them as we have in the past? This is the key question for contemporary indigenous art: Is it a genuine connection between cultures, something that can teach everyone and help us all reconnect, or are we simply using it in the same way as before?

For me, it’s the same thing. This exhibition is an opportunity for a discussion on the same level. It gives the communities a chance to talk about themselves and express their own voices for the first time, as it’s rare for communities in the Amazon to be heard. We are always looking at them, talking about them, but they rarely get the opportunity to speak for themselves or engage in discourse at the same level. We are trying to do that, but it’s incredibly complicated from the perspective of a European institution. It’s something that really breaks the norms. It’s also been difficult for me because I still carry aspects of the colonial mindset. So, I’m trying to speak on the same level, trying to do something different, to learn from them, and to provide them with the opportunity to express themselves. I believe this is absolutely necessary. The question is, in these times, with everything happening in the world, can we truly open up the discussion and talk with different communities on the same level, or are we still using them and treating them as we always have? For me, this is the most complex aspect of this moment, and I don’t have the answer. I’m trying to do it, but I don’t know if I can.

'Amazons. The Ancestral Future’ Installation image, 2024 / CC BY-SA-NC Martí Berenguer. Courtesy of CCCB Barcelona

Yes, I think it’s a long way because we need to overcome those stereotypes in our minds. Otherwise, we are always following the same pattern. You try, but you need to find new pathways. Maybe this is why we are turning to these teacher plants nowadays – they are important for our survival and for finding new ways of thinking. This is why they are coming to us.

And that’s the reason we have a curatorial community with nine people coming from the Amazon. We decided to do this, but it’s such a complicated process because in Europe, we think that we are the center of the world, and that hasn’t changed in many years. So now, we are only looking at what happens in the world, but we don’t understand much because the roles are changing, and we still think we are in the center, which is not the case. And that’s interesting.

I also wanted to ask you about the choice of the artists because some of them are really special. For example, Kitchwa painter Elías Mamallacta from Ecuador. There is a story where he claims that his grandmother became a puma, which, for indigenous people, I think, is quite normal...

But it was so crazy because he was at the exhibition explaining to everyone, “Oh, my grandfather was a puma...” And the mural by Elias is amazing because it’s made with Sangre de Drago and Ayahuasca. He brought it to Europe in bottles, but we lost the baggage for three days. Sangre de Drago is red, and its color keeps changing because it’s alive. In Elias work, each colour has its own meaning. Each of these meanings is firmly associated with events in the social life of the Amazon and the rituals that transform the subject matter of his paintings into something magical. His work is incredible, not only because of the materials but also because of his deep connection to it, and he talks about that with everyone here.

One really important part of the exhibit is that nine indigenous artists came to Barcelona to create the exhibit. This makes it truly unique because they designed the pieces specifically for Barcelona, responding to what they felt was needed. For example, Hunikuin, a shaman from MAHKU collective, said, “We need to heal you because you carry a lot of negative energy.” So, he created his work to help us reconnect with nature and live in harmony in Europe. He determined that we are really, really sick. It was crazy, indeed.

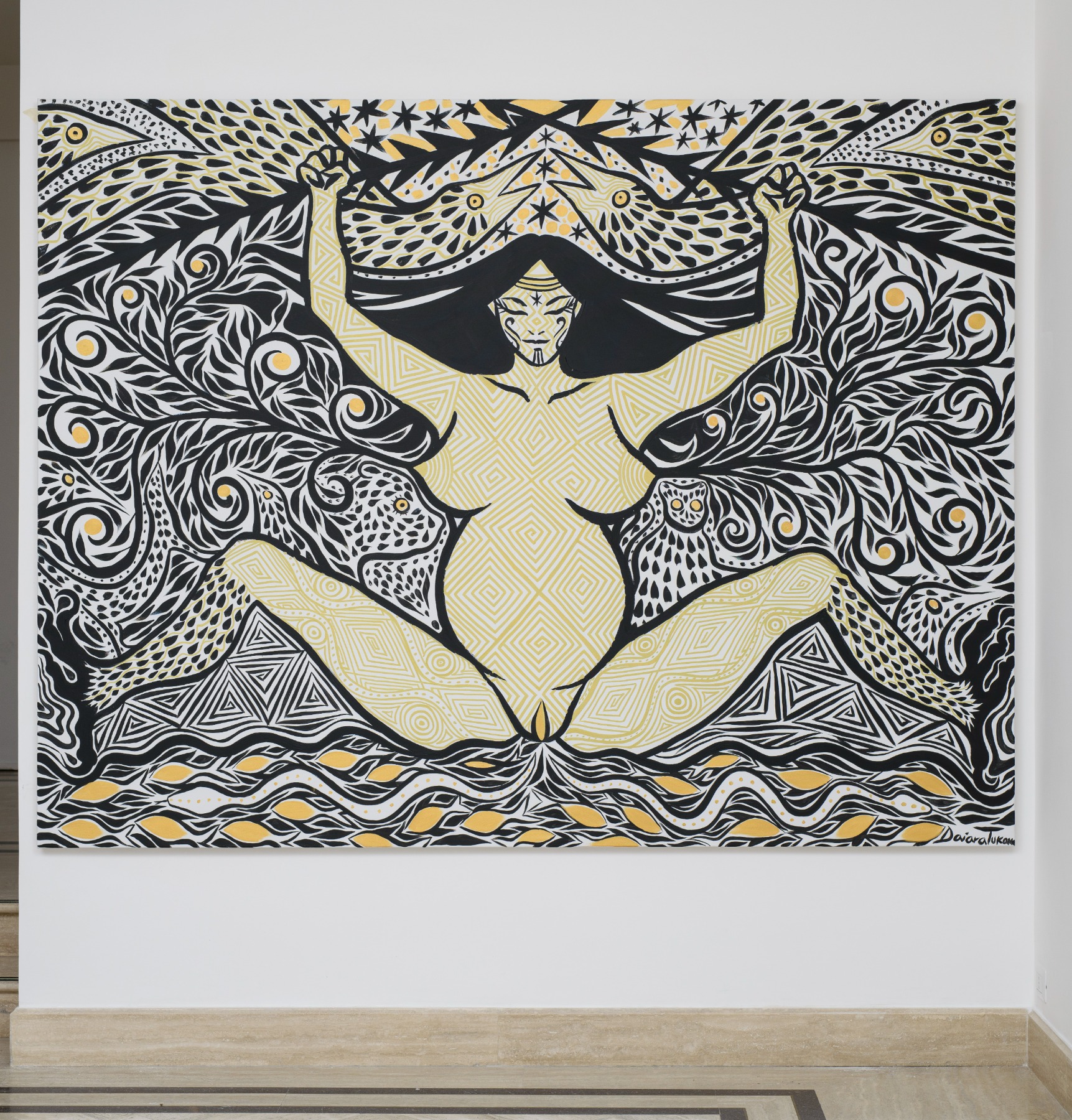

Daiara Tukano, Ohpeko Pati, món de les aigües sagrades de la gran mare de l'univers (2023). Ink on paper. Courtesy Richard Saulton Gallery, London, Rome, New York, and Millan, São Paulo

You also have Daiara Tukano, who is quite well known among those interested in indigenous art.

I think we have an interesting mix because we have some well-known artists from the Amazon, like MAHKU collective and Daiara—they are the principal voices from the region, and it was important for me to present their work in the exhibit. But then we also have other artists like Elias, Paulo Desana – people who are not really known here. We also have Olinda Silvano and Cordelia Sánchez. For Cordelia, this was the first time taking an airplane to travel to Europe or even leave Peru, and the same goes for Elias. So they are experiencing traveling outside their countries for the first time. I think this mix is interesting because we have famous artists from the Amazon alongside other kinds of artists from the region, creating a diverse and rich dialogue.

'Amazons. The Ancestral Future’ Installation image, 2024 / CC BY-SA-NC Martí Berenguer. Courtesy of CCCB Barcelona

Do you think that the exhibition could also serve as a lesson for us to go deeper into our own origins, the origins of our own cultures?

I would love that, but I’m not sure if that’s the point I started with. However, I think it could be a good direction. For me, the starting point of this initiative is to think about us, not just the Amazon. It’s important to talk about the Amazon and how we can create different kinds of connections. In the Amazon, you have the opportunity to hear the ancestral voices of many communities that have been resisting for over 500 years, facing the environmental and deforestation processes coming from Europe and the United States and China. We don’t have many other parts of the world where you can hear these voices. One anthropologist from Colombia told me that the Amazon is the last place in the world where this is still happening.

We are quickly creating a new society, but we still have the ancestral knowledge alive, combined with the influence of modernity in the same space. It’s a shock, but in this shock, we have many opportunities to change, and they can change many things as well. The idea of the exhibition is not to romanticize the life of the indigenous people or make it seem like everything is amazing and beautiful – it’s not a project based on that ideal. It’s more like: Maybe together, we can help each other as a world, and maybe we can do something for ourselves.

For us, the most difficult thing is to avoid this distinction between ‘us’ and ‘them,’ because we are all one. But it’s really difficult.

Sure, I’ve been working on that for the last 30 years, and I’m not sure if I can do it. So, it’s complicated, but it’s the only way we can continue in this society. We need to learn many things, and we need to change our paradigm. Our cultures need to move in the same direction, because right now, we are heading in the opposite direction. It’s like we’re contributing to taking away everything from the future. We’re not considering the consequences of all kinds of life. We’re not thinking about the impact of our actions. We’re polluting the world, taking everything without thinking about the future. So, I think we need to change. I was talking with Paulo Artaxo, a scientist from Brazil, and he told me, ‘I’m optimistic, because if we don’t change, our society will break. We need to change, so that’s the only way we can make it.’ So, I’m optimistic because, if not, we are heading for disaster.

Amazons. The Ancestral Future is open in the CCCB, Barcelona until May 2025.

Title image: Claudi Carreras. Photo: Nicolas Janowski