Flags of Shifting Perspective

An interview with Indian artist Jitish Kallat on the occasion of his installation Adrift Signs, a part of the raising flags project by museum in progress in Vienna

raising flags is a long – term project by museum in progress that has been realized at various locations since 2023, including virtual exhibition spaces online and media spaces in newspapers and magazines. In addition to Vienna’s Stubenbrücke, the project was showcased in June 2024 in Ladakh, India, at the sā Biennale at an altitude of 3,600 meters, and in Bad Gastein as part of sommer.frische.kunst (summer 2024). At the beginning of 2025, a presentation was held in Ahungalla, Sri Lanka, in collaboration with One World Foundation and Raki Nikahetiya.

The first phase of raising flags, which began on May 1, 2023, was titled Nation Flags of Ideas and explored questions of social coexistence in challenging times. museum in progress has reclaimed a space for art at the Stubenbrücke, which for many years was defined by the lemur heads of Franz West. Stretching along the Vienna River to Oskar Kokoschka – Platz, this public space was transformed into an art zone. Since then, more than 35 artists have participated in this project, including Erwin Wurm, Eva Schlegel, Jonathan Meese, Laure Prouvost, and others.

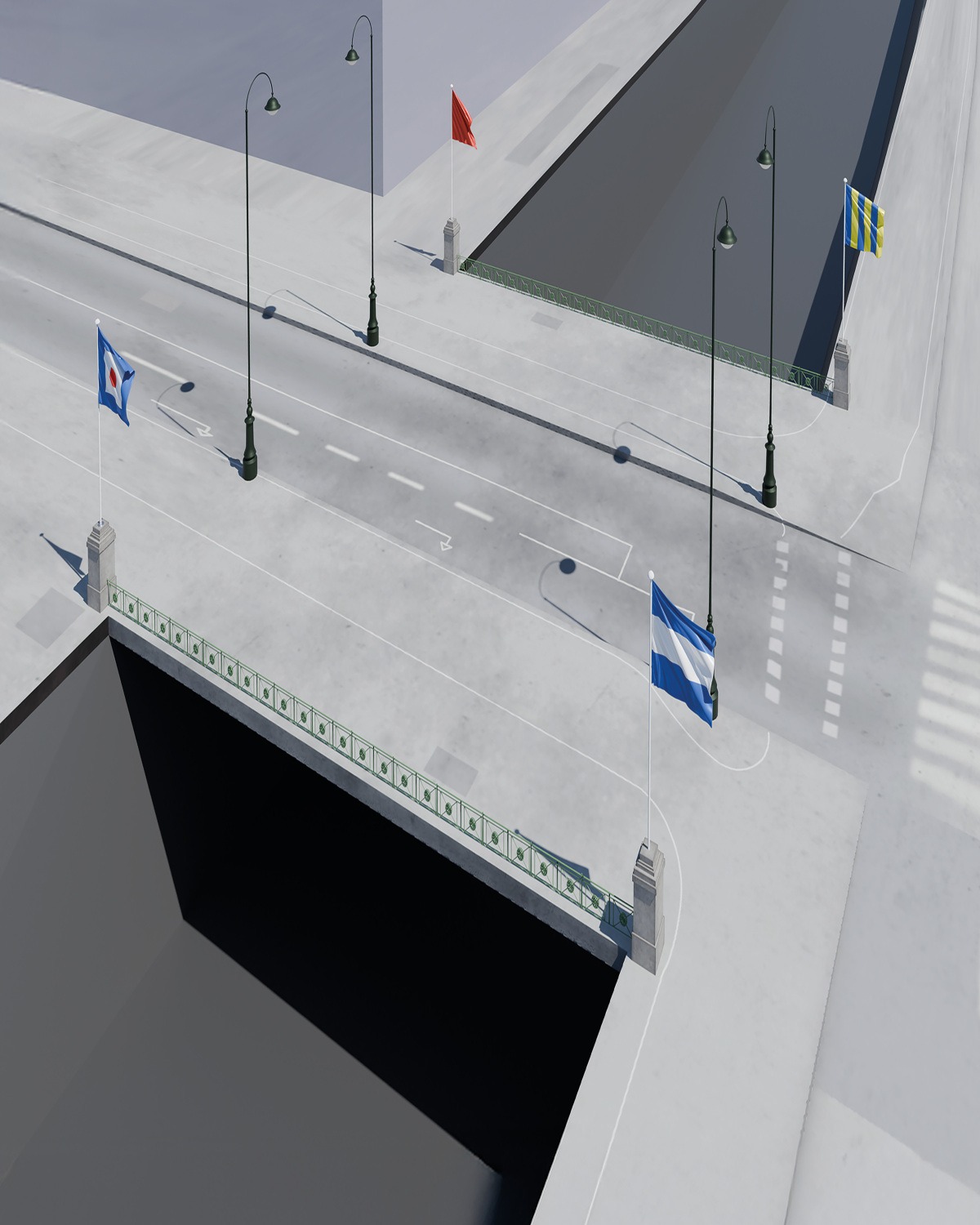

From March 10 to May 22, raising flags is hosting a solo public installation by renowned Mumbai – based artist Jitish Kallat. Titled Adrift Signs, it features four nautical flags displayed at Vienna’s historic Stubenbrücke. Their cryptic maritime codes extend beyond the sea, standing on land as signals from the larger planetary vessel on which we move through the universe.

According to the project statement, the flag bearing the message “I require a pilot” can be read as a call for absent stewardship in a world adrift. “Keep clear of me. I am on fire and carrying dangerous cargo” speaks to an inflamed and volatile planet. “I require medical assistance” becomes a plea for urgent intervention. “I am carrying dangerous goods” signals the hazardous burdens threatening our collective survival.

Each flag is part of the International Code of Signals (ICS), traditionally used at sea to communicate urgency and survival. Here, they mark Stubenbrücke as a site of planetary reflection – a threshold between awareness and action.

Jitish Kallat was born in Mumbai in 1974, where he continues to live and work. His vast oeuvre spans painting, photography, drawing, video, and sculptural installations, revealing a constant engagement with ideas of time, sustenance, recursion, and historical recall. Weaving together strands of sociology, biology, and archaeology, the artist takes an ironic and poetic look at the altered relationship between nature and culture.

His works have been exhibited widely in museums and institutions around the world, including Tate Modern (London), Martin – Gropius – Bau (Berlin), Mori Art Museum (Tokyo), Gallery of Modern Art (Brisbane), and Institut Valencià d’Art Modern (Spain), among many others. He curated the Kochi – Muziris Biennale in 2014 and represented India at the 58th Venice Biennale in 2019.

Our conversation takes place over Zoom – between the launch of Adrift Signs in Vienna and the opening of Kallat’s Covering Letter: Terranum Nuncius project at the Kennedy Center in New York.

Jitish Kallat, Adrift Signs (I am carrying dangerous goods), 2025, four nautical flags, raising flags, museum in progress, Stubenbrücke, flag

What makes museum in progress’ raising flags initiative important to you as an artist?

The most exciting aspect for me is the real possibility of public engagement – creating something in the street that doesn’t announce itself as a conventional artwork but rather as a sign, a subtle yet powerful presence in public space. That, I think, is particularly important.

During my previous visit in Vienna, I had walked on that bridge, so I already had memories of it. It felt like those four corners could truly become a significant site. And knowing that whatever I create now as part of the project will later take on new forms – reincarnating in other flag – raising moments – makes it feel like an evolving, ongoing process.

When I was looking at the pictures of your work Adrift Signs and the nautical codes you use, I was thinking about how today we are once again trying to emphasize the importance of conversation and negotiation in many difficult geopolitical situations. We keep talking about the need for dialogue between different cultures, yet the more we try, the less successful it seems. In a way, the International Code of Signals functions as a universal language. I don’t know if that’s the reason you chose these specific signs, but to me, they feel universal – something we can all understand.

Yes. I think that’s a really beautiful observation. To me, it was about finding – well, in a sense, a flag itself is already a universal sign, right? So I wanted to match it not with an external form, but with the essence of what a flag is. The International Code of Signals isn’t just an image of a flag; it is a flag.

The only real shift here is its location. Instead of being at sea, it’s on land. And more interestingly, it’s on a bridge – a transitory space. In this first instance, it exists in that in – between space. But if we extrapolate further, the flag is ultimately on the planet itself – a kind of vessel, an adrift object in its own right. Earth follows its orbital path, yet everything on it is, in a sense, adrift.

For me, nautical codes and signals speak to the idea of navigation and journey. But by placing them in this context, the vessel becomes the planet itself, carrying different signals – perhaps four different signs. And as people walk among them, it creates a kind of transitory movement, a space for reflection. The bridge, then, becomes not just a passageway but a site for contemplation.

But why did you choose those four specific signs? The International Code of Signals has a whole system of signs – you could have chosen entirely different ones.

Yes, I mean, there are many signs within that code that could have worked. After all, raising a flag itself is already a signal – often one of alarm. When we say raising flags, it’s not just about the physical act; we raise flags because there’s something to announce. And usually, you raise a flag or sound an alarm when something urgent needs attention.

Many of the flags in the system convey different kinds of urgency. But these four, in particular, became significant – one signaling a call for leadership, another indicating hazardous materials on board. To me, that last one resonates deeply, almost as a metaphor for an autoimmune condition of the planet – the fact that we are carrying things within our world that can ultimately harm it.

Jitish Kallat, Adrift Signs (I require a pilot), 2025, four nautical flags, raising flags, museum in progress, Stubenbrücke, flag

Are you raising these flags for society to see them, or are they also meant as signals to something beyond us – perhaps to universal forces, since you mentioned that we’re living on a drifting planet?

You know, one of the recurring themes in my work is this notion of the planetary – but always within a framework that expands our focal length, both in space and time. Some of my works go back to historical moments – letters, speeches, documents. And when we reread those historical texts, we simultaneously reread the present through them.

Another key aspect of my work is a shift in spatial perspective. Just as history allows us to shift our understanding of time, I like to introduce a shift in space – where we read our terrestrial reality from a celestial distance. And when we superimpose those perspectives – when we recognize that we speak of vessels while being on a vessel ourselves – that simple realization can produce a powerful shift in intuition.

It makes us reconsider scale: the scale of this planet as a vessel, the larger cosmic journeys we are part of, our place within them, and even our urgencies and existential crises. Seeing ourselves as part of this vast system allows us to rethink the magnitude of our challenges and our role in them. This shifting perspective – this awareness of the planetary within the universe – is a recurring motif in my work. And here, in this project, it’s woven in quite subtly, but it’s still very much present.

Jitish Kallat, Adrift Signs (I require a pilot), 2025, four nautical flags, raising flags, museum in progress, flag edition

Photo: Rudolf Strobl, Copyright: museum in progress

You’re kind of pushing both yourself and the viewer beyond their usual boundaries – beyond the body, beyond the limits of perception. I remember an interview in which you mentioned that sometimes in your studio you push yourself to stare at the sky for a long time. I find that approach really interesting – it’s like you’re receiving information that’s already there, even if you don’t necessarily know the code for it. By stepping outside your ordinary frame of reference, you somehow open yourself to it.

That’s right. In fact, I currently have a solo project at the Kennedy Center in Washington, at the Hall of Nations. The installation is centered around the 116 images that were sent into space in 1977 aboard the Voyager 1 and 2 missions – a kind of summary of life on Earth, intended for an extraterrestrial intelligence.

In a way, the work reflects on the idea of creating a vocabulary – a record of a past time meant to be read in a distant and unknown future, by a distant and unknown intelligence, most likely long after we’re gone. These shifts in perspective – between time, space, and perception – allow us to reconsider fundamental questions about the self and the other. And in this case, the other is something entirely unknown, which in turn invites us to rethink how we perceive the immediate other – the people just across a political or religious boundary.

How do we reconsider these divisions when we take a step back and look at them from a greater distance? What happens when we apply the same expanded perspective we use for interstellar communication to the way we understand each other here on Earth? That’s a question that runs through much of my work. You can find this particular project on my website – it’s called Covering Letter: Terranum Nuncius – along with other works where this shift in perception is central.

Jitish Kallat, Adrift Signs (Keep clear of me. I am on fire and carrying dangerous cargo), 2025, four nautical flags, raising flags, museum in progress, Stubenbrücke, flag

It’s interesting because historically, maritime journeys have also reshaped our perception of the world. Whether driven by trade – like the spice routes in Kerala – or by exploration, they’ve dramatically altered the maps of our world. Do you feel like we’re living in a time when maps could change once again, perhaps in a less fortunate way?

It’s really interesting that you bring up maritime journeys. One of my larger curatorial projects, exactly ten years ago, was for the Kochi-Muziris Biennale in 2014. The heart of that project was an inquiry into history and cosmology through the Age of Discovery.

Much of the nautical movement in the 13th to 15th centuries was about reaching the shores of Kerala – an era we now call the Age of Exploration. But alongside exploration came colonial subjugation, and these shifting histories were central to my curatorial approach.

Beyond that, what fascinates me is that during the same period, Kerala’s mathematicians were laying the groundwork for trigonometry and calculus – about 150 years before Newton and Leibniz. Recent mathematical research has traced back the roots of these discoveries to Kerala. So, in many ways, the same shores that saw the arrival of European explorers were also producing a new way of understanding the world through mathematics.

Now, coming back to your question about maps – yes, I think we are at a moment where maps could change again, but in a very different way. We’ve reached a point where there is almost no terra incognita left; every inch of the world has been mapped. But despite all our knowledge, we are starting to realize that there are fundamental misunderstandings about our own existence on this map we’ve drawn so precisely.

We have mapped everything, yet we don’t seem to know what to do with that knowledge. In some ways, our understanding of the world is beginning to harm us – it’s an autoimmune condition of sorts. So perhaps the new maps we need to draw are not geographical ones, but maps of resetting – maps of protocols, of conduct, of stewardship. Maybe what we need are maps that guide us toward responsible ancestry – toward a way of living that acknowledges our role as caretakers of this planet.

Jitish Kallat, Adrift Signs (I require medical assistance), 2025, four nautical flags, raising flags, museum in progress, Stubenbrücke, flag

That’s a powerful idea. And it brings me back to the notion of the flag. For a long time, flags have symbolized national or regional identity – something we take pride in. In Latvia, we also raise flags on specific dates to mark moments of mourning, commemorating events such as the Communist genocide and the genocide of the Jewish people. But with the flags you place on the bridge, it feels like you’re suggesting a new kind of flag – flags of urgency. That completely shifts the paradigm of how we are used to seeing flags, especially in times of peace.

That’s right, yes. And you bring up an interesting point – most traditional flags represent a smaller circle of belonging, tied to national identity or cultural affinity. But the flags I use exist in the in – between spaces. They are not national flags but signals—flags of the ocean, where ships from different nations use the same visual language to communicate.

At sea, regardless of where a ship comes from, it can send a message that will be understood by another vessel using the same code. In that sense, these flags represent a kind of yearning – for a shared language, a way to communicate across boundaries. That’s something we need now more than ever.

Looking back at your work, you’ve always been interested in big questions – birth, death, mortality. Are you still searching for answers?

I think I’m searching for better questions. I don’t believe I have answers – perhaps just slightly more refined questions or more meaningful pointers.

One of my projects from 2021 was a suite of 365 drawings. These drawings, called Integer Studies: Drawing from Life, were created one per day from January 1st to December 31st, 2021. Each carries three numbers: the estimated number of people alive at the moment I began drawing; the estimated number of people who had passed away since midnight the previous day, and the estimated number of births.

These numbers became a kind of device – almost like a thought experiment – through which I could reflect on life, death, and existence. Between my first and last drawing, the global population increased from 7.8 billion to over 7.95 billion. And while working with these vast, abstract numbers, I sometimes found deeply personal moments – like a number ending in four, which matched the number of members in my family.

At times, writing out these figures felt like reducing “humanity” or the “human race” to pure abstraction. But that abstraction allowed me to see it differently, to grasp something intuitive about our collective existence. These kinds of rituals continue in my studio practice, constantly shifting my perspective.

Have you managed to answer what is perhaps the most fundamental existential question: Who am I?

That is the fundamental question. And precisely because of that, all one can really do is point to it.

Art, philosophy and science all operate within the relative, where meaning is created through relationships and contrasts. But this question – Who am I? – exists in an entirely different space. At best, I think art serves as a tool that points toward it.

For instance, if I say, I am adrift as the planet is adrift, there’s a resonance between the self and the world. Perhaps if I weren’t adrift, the planet itself wouldn’t be adrift. It’s a kind of extrapolation – moving from the self to the cosmos, from the personal to the planetary.

Jitish Kallat, Adrift Signs (I require medical assistance), 2025, four nautical flags, raising flags, museum in progress, flag edition

Photo: Rudolf Strobl, Copyright: museum in progress

A journalist once asked you, “What is art for?” And you answered, in my eyes, very beautifully, saying that art is a device for seeing the world. But I’m wondering – how can we learn to use this device most efficiently? We have many devices available to us, created to help us, yet we use them for a while, then discard them when we get bored. But art has been with humanity since the beginning, and still, especially in these times, we struggle to understand its value and how it can help us, even in situations like this. What would be your advice?

You know, yeah, this is actually interesting that you brought it up because, you know, I often say that art is not something you look at, but something you look through. So even when I curated the Biennale – the second edition of the Kochi Biennale – I often said that the Biennale itself is an observation deck. It is not something you merely look at (though you might), but something you look through. It is best used as a viewing device rather than an object of viewing.

I hold that belief, and I think anything of value that I’ve created, in terms of meaning, tends to repurpose itself and find new meanings. Let me give you an example from this morning. I just received a message from a curator friend, who was previously at MoMA and happened to be in Chicago last night. So I woke up to his message. He was at the Art Institute of Chicago, where I currently have the solo project Public Notice 3 on view [until September 2025 – Ed.]. The risers of the museum’s steps display a speech delivered on September 11, 1893, at the first Parliament of Religions. The speech is installed on the steps of the museum – exactly where the Parliament originally took place. So, the speech overlaps both site and date, but it is also coded in the five colors that U.S. Homeland Security once used to indicate threat levels after 9/11.

Now, interestingly, this friend of mine from MoMA sent me a message saying that my work couldn’t be more urgent today. He sent me a screenshot showing how the five Homeland Security colors – red, yellow, orange, blue, and green – were originally used to indicate terror threat levels in the United States. But he also included another screenshot showing how the Trump administration has now applied these same colors to categorize visa applications: yellow for certain countries, orange for others, red for others. The codes I originally used in my work were actually discontinued ten years ago by the Obama administration, after being introduced by Bush 20 years ago. But now, a new administration has brought back the same color–coding system, applying a completely new layer of meaning to those same colors.

And yet, my artwork’s embedded speech calls for an end to fanaticism, fundamentalism, bigotry, and intolerance. It’s a long answer, but it’s exactly what I woke up to today – how an artwork does not simply produce meaning once, but rather, reorients and readjusts itself to the meanings that the world projects onto it. For me, anytime I’ve created an artwork with intrinsic meaning, it has continually rephrased its meaning over time.

And if we see art as a viewing device, it will always point beyond itself – it will always be a lens through which we look at the world.

Thank you very much!