A call to a more humanist relationship with the world

An interview with Gary Carrion-Murayari, Kraus Family Senior Curator at the New Museum, on the occasion of the opening of In a Bright Green Field, an exhibition organized by the New Museum and the DESTE Foundation in partnership with the Benaki Museum in Athens

Greek artist Nefeli Papadimouli’s magnificent, magical, and meditative 30-minute performance—at moments reminiscent of a mystical Sufi dance, aiming to transcend the self, time, and space—took place in the lobby of the Benaki Museum in Athens and symbolically marked the beginning of a weekend filled with art, conversation, new encounters, unprecedented sensations, and fresh ideas. In the second half of June, immediately after Art Basel, all art paths lead to Greece—first to Athens, then to the island of Hydra. The tradition established by Greek collector Dakis Joannou and his DESTE Foundation has become an integral part of both the local and international cultural landscape. Within the local community, the event has already earned the unofficial name “DESTE Art Week.”

Athens’ art scene is thriving these days, with numerous exhibition openings in galleries across the city and strong institutional shows. It is undeniable that Dakis Joannou’s contribution to the development of the Greek contemporary art scene and its growing international recognition is invaluable—and has already inspired many others to follow in his footsteps, helping to make Athens’ art scene truly exceptional.

The exhibition In a Bright Green Field, on view at the Benaki Museum – Pireos in Athens until 13 September 2025, marks the third collaboration between the DESTE Foundation and the New Museum. Like the two previous exhibitions—The Equilibrists (2016) and The Same River Twice (2019)—this show highlights the work of contemporary Greek and Cypriot artists, engaging with the passage of time and its challenges. Through art, it builds bridges of ideas and knowledge between the past and the future, provoking a deeper reflection on how we might imagine and find possible solutions.

Installation view, In a Bright Green Field

Benaki Museum, Athens (June 11–September 13, 2025)

Photo: Giorgos Sfakianakis

In a Bright Green Field presents the work of twenty-nine emerging artists under the age of forty. Together, they explore the complex narratives of today’s world—the tensions and differences that seek resolution within the shared fabric of the time and space we all inhabit. The exhibition envisions possible futures in which renewed relationships with the natural world may emerge and expansive forms of community can flourish. In doing so, it seeks a deeper understanding of what it means to be human, and how we might preserve and nurture our humanity in a world where instability and madness have become the new normal. Featuring a wide range of media—including painting, sculpture, installation, digital, and video art—the exhibition showcases some of the most exciting and dynamic young artistic practices in Athens, Nicosia, and across Europe.

Many of these artists come from diverse disciplines—such as architecture and anthropology—and this interdisciplinary background makes them keen observers of the world around them. They register the dramatic transformations in labor, landscape, and social relations accelerated by technology, while also illuminating emergent forms of collectivity across both urban and rural contexts. Their works explore the poetics of infrastructure, pastoral science fictions, the unnoticed beauty of small, ordinary things and materials, questions of identity and belonging in times of global unrest, urban animism, mythology, generative collaborations, and new models of coexistence. Ranging from lyrical, almost spiritual painting and sculpture to experimental documentary film and digital visions, In a Bright Green Field presents artistic practices that—grounded in local knowledge, history, and a deep sense of community—serve as prototypes for myriad possible futures.

Installation view, In a Bright Green Field

Benaki Museum, Athens (June 11–September 13, 2025)

Photo: Giorgos Sfakianakis

Similar to Nefeli Papadimouli’s performance—which manifests a desire to engage both the bodies of dancers and spectators through action, impulsive gestures, stimulated behaviors, and heightened senses—the exhibition illustrates that the individual cannot exist without the collective. The beauty of a pattern lies in the synchronicity of its diverse elements. In this way, the exhibition becomes a manifestation of the idea that the “I” and the “We” are far more interconnected than we often imagine.

The exhibition is curated by Gary Carrion-Murayari, Kraus Family Senior Curator at the New Museum, who noted in our conversation: “If I do have hope, it comes from these artists. I think that if change is possible, it’s going to come from the imagination of a better future.”

Installation view, In a Bright Green Field

Benaki Museum, Athens (June 11–September 13, 2025)

Photo: Giorgos Sfakianakis

I would like to ask if the exhibition title In a Bright Green Field refers to a kind of metaphorical place—a place we all arrive at after personal and communal loss and recovery, after all this transition and transformation?

Yeah. I mean, I think any title for a group show needs to operate on multiple levels—especially with this show, which is both thematic and also meant to be a kind of survey of this generation. I think the title addressed a lot of things I had been thinking about outside the show, but also the specific concerns of the artists in relation to what’s happening in Greece and Cyprus in particular, and how those issues might help us think about larger global questions.

So I think, yeah, you can read it on a more specific level—in that the show is, in some ways, about landscape, and in some ways about the environment—but it’s also a kind of metaphor for how we might come together in a space to imagine the future in productive ways.

Installation view, In a Bright Green Field

Benaki Museum, Athens (June 11–September 13, 2025)

Photo: Giorgos Sfakianakis

How would you characterize this generation of Greek artists, all of whom were born in the 1980s and 1990s and are now approximately in their late 30s?

You know, for this particular show, I wanted to look at the artists who have emerged since I did the first show ten years ago—which was a very different moment in Greece, especially in Athens. It was a completely different landscape, in the depths of the crisis.

The generation that has emerged since then has had both different opportunities and a different kind of relationship with the broader contemporary art world in Europe. There’s obviously much more attention paid to the Greek art scene now than there was before.

So I was looking at artists under 40, but really, the idea was to offer a kind of survey of what has happened in the years since, and how the approach of artists working today might differ from those who emerged a decade ago—when opportunities were more limited, and the outlook on the future in Greece was very different.

Installation view, In a Bright Green Field

Benaki Museum, Athens (June 11–September 13, 2025)

Photo: Giorgos Sfakianakis

But what’s your gut feeling about the Greek art scene right now? For me, after attending DESTE events for almost ten years, the change is remarkable. In the beginning, it was a tense time—Greece had just come through a deep crisis—but now the scene feels genuinely vibrant. The whole ecosystem is booming.

I think one thing that came out of the first show was how surprising it was to people just how much was happening here—even during the crisis. The infrastructure and institutions have changed a lot since then. Back then, EMST hadn’t even opened yet. Since the first show, projects by foundations like Onassis and Stavros Niarchos, among others, have become more active, especially in supporting younger artists.

But even during the crisis, there was a lot happening. Artist-run spaces were thriving, which has always been a strong part of the art ecosystem in Athens. Many of the artists who are now in their mid-40s had studied in London or elsewhere in Europe and were starting to come back to Athens. Some split their time between those cities and Athens—it was cheaper to produce work here, so often the production happened locally, while they continued showing internationally.

I think part of the surprise at the time was because that generation was so dispersed. What’s happened since is that many artists—even from that generation—returned during COVID. And importantly, in recent years there’s been more support for young curators and writers too, which has really elevated the scene.

Of course, after documenta, when more people began moving to Athens from across Europe, it also became a more attractive place for galleries to open. We’ve seen younger galleries—both Greek and non-Greek—setting up here. Many are incredibly smart, exciting, and bring real enthusiasm to the scene. All of that has contributed to this sense of vibrancy.

But at the core of it, I have a strong belief in Greek artists. Even during the toughest times, they sustained the scene. Without that committed effort by those who stayed and kept things going through the crisis, the art scene here wouldn’t be what it is today.

Installation view, In a Bright Green Field

Benaki Museum, Athens (June 11–September 13, 2025)

Photo: Giorgos Sfakianakis

In your opinion, what makes Greek artists different? There’s definitely something that makes them stand out—I don’t know if it’s history, culture, or something in the DNA, but it’s there.

I think for both Greece and Cyprus, the number of good artists is kind of surprising given the size of the cities. I’ve said this to many people—I’m not sure I could put together a show like this in many other European cities, where you could have a full exhibition made up entirely of local artists. And Cyprus is even more surprising. There are so many great artists from there—some of my personal favorites, actually.

Education definitely plays a role, but history is also really important. Though I wouldn’t necessarily point to ancient history. In fact, I think ancient history has been a bit of a burden for Greek and Cypriot artists—it created an expectation that their work had to engage with that legacy. What I think really shapes these artists is modern history—recent history—in both Greece and Cyprus.

These artists are often more politically engaged and aware than many others working in bigger, more stable, or wealthier centers. They're very conscious of their geographical position in the world. In this show, for instance, you see themes like ecology, climate, migration, and the nature of community—questions that are deeply embedded in what it means to be Greek or Cypriot today. These are issues they’ve been dealing with for decades, and the younger generation is especially aware of them.

They’re also actively seeking connections outside their immediate environment. One great example is the collective Latent Community, which does projects across the Mediterranean. Cypriot artists in particular are very attuned to how their history differs from that of Greek artists—they understand their position as distinct. Cyprus is geographically closer to Lebanon than to Greece, and I think that fact alone shapes how Cypriot artists view themselves and their place in the world.

So I think it’s all these material conditions—education, politics, geography, history—that make these scenes so vibrant. Beyond that, I’ve just been really lucky to work with such amazing artists. They’re incredibly collaborative and supportive of one another. And because, for a long time, they didn’t get much attention or support from the outside, that sense of connection and care really comes through in their practices. It all ties back to a deep understanding of the histories—recent histories—of the places they come from.

Installation view, In a Bright Green Field

Benaki Museum, Athens (June 11–September 13, 2025)

Photo: Giorgos Sfakianakis

Did you already know all the artists beforehand, or was it a research and discovery process for you as well?

No, it’s very much research. I come to Athens often anyway, so I try to keep up with what’s happening here. I have many friends who are artists and curators, so I’m somewhat aware. But the real fun of the show is doing that research over an extended period—coming to Athens multiple times, discovering new spaces, and finding out where things are happening.

There were a handful of artists whose work I knew, maybe a bit superficially or from seeing them in shows elsewhere in the world. But most of the artists I encountered through the research process. That’s the best part.

What’s really exciting about these shows is having the chance to build an extended relationship. When you do research at a museum in New York, for example, you might visit a place once and try to get as much done as possible in one trip. But here, I could come multiple times, developing deeper connections.

Also, having connections from previous shows helps—I don’t enter this process alone. There are many voices and dialogues that feed into it. I think that’s what brought out some names that might have been less familiar even here in Athens, because the larger community contributed to the show.

Installation view, In a Bright Green Field

Benaki Museum, Athens (June 11–September 13, 2025)

Photo: Giorgos Sfakianakis

It was also interesting to discover that some of the artists included in the show are interdisciplinary, with backgrounds in fields like architecture—for example, Nefeli Papadimouli.

Nefeli Papadimouli, like many of the artists, went to architecture school. That’s actually a very Greek kind of thing, I would say. Greek artists tend to be more highly educated—they often hold advanced degrees in fields outside of art, more so than in many other parts of the world. Everyone probably has their own reasons for that, but from the conversations I’ve had, there seems to be a kind of practicality behind it. It’s often about proving to your parents that you have a set of practical skills to fall back on if your artistic career doesn’t take off.

But what’s really interesting is how those other fields of study feed into the work in meaningful ways. Nefeli’s practice, for example, is very much in dialogue with architecture. Theo Triantafyllidis creates these immersive digital environments, and many of the technical skills he uses came through his background in architecture. Konstanza Kapsali, one of the filmmakers in the show, studied archaeology and anthropology—and you can see that in the way she uses anthropological methods in her collaborative, socially engaged documentary work.

So all of those tools—their prior studies—really enrich the themes the artists are working with. They have a strong sense of how their work relates to the world, not just through object-making, but through broader intellectual and social frameworks. I'm always surprised to learn what each artist studied—it’s rarely what you’d expect—but that interdisciplinary curiosity really does feel like a particularly Greek characteristic in this context.

Installation view, In a Bright Green Field

Benaki Museum, Athens (June 11–September 13, 2025)

Photo: Giorgos Sfakianakis

Nefeli Papadimouli’s performance in the hall of the Benaki Museum was a mind-blowing experience. It evoked the magic of Sufi dance and revealed her deep sensitivity to space and movement—how the dancers felt and responded to the architecture through their bodies.

Yeah, it was beautiful. In her work, the dancers are truly collaborators within the piece. She develops the choreography together with them, and it’s not always the same group—sometimes it includes people who aren’t professionally trained, depending on the project. She’s very responsive to the relationships that develop during the process, as well as to the architecture of the space itself. It’s a really fascinating approach, and as you said, the result is always quite beautiful.

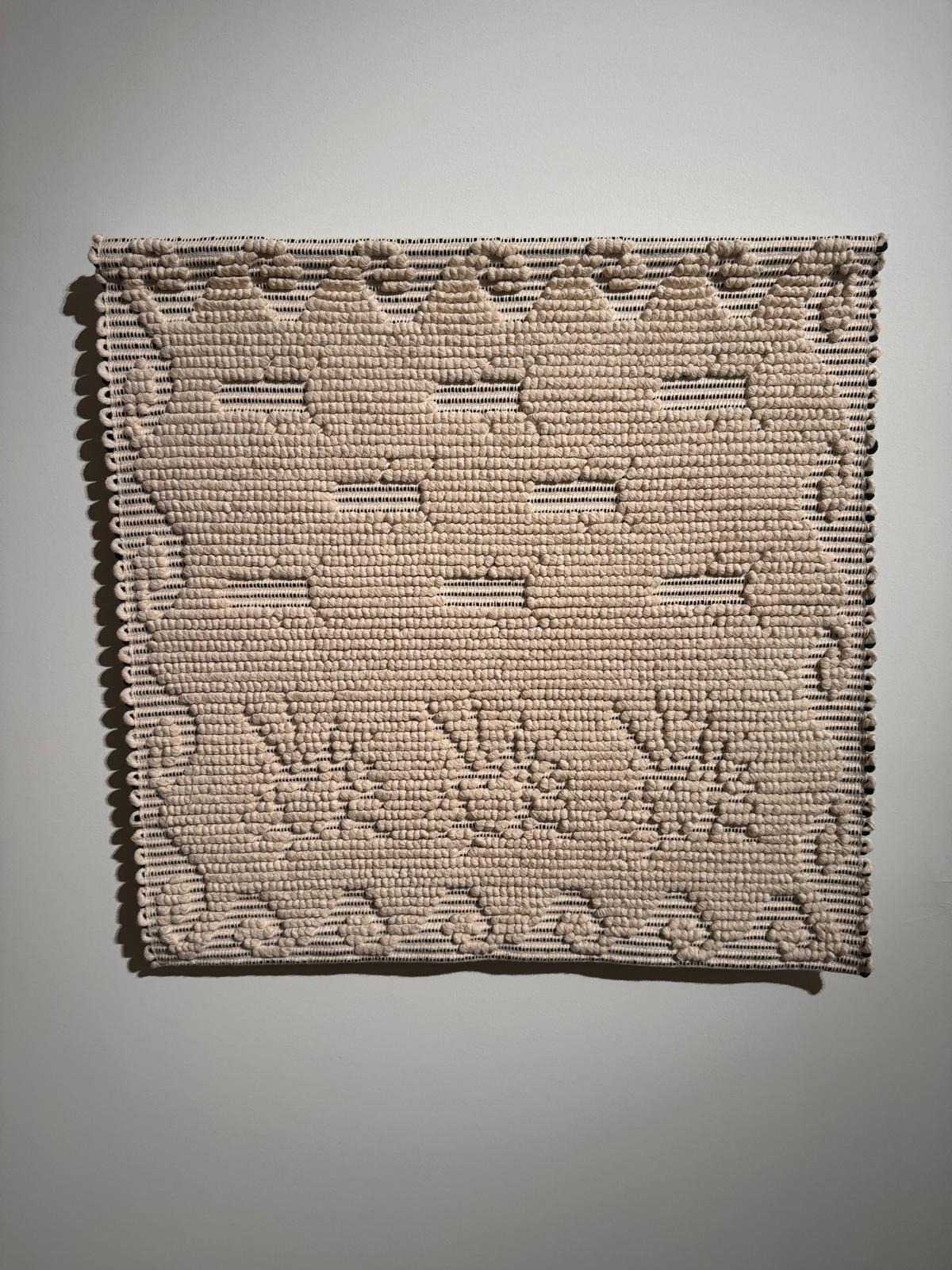

Latent Community. Pibiones (War Rug #2), 2024. Handmade Woven Tapestry.Photo: Arterritory.com

I also find Latent Community's work really interesting, especially the textile pieces titled War Rugs. In a way, they reminded me of the history of Afghan war rugs from the time of the Afghan-Soviet war. Afghan carpet weavers reflected on the conflict by incorporating images of tanks and other military hardware into their designs.

For those specific pieces, they were made in Sardinia, using traditional Sardinian rug-making techniques. Of course, textile traditions span the entire region, but this was a particularly interesting process. For Latent Community, their work is always deeply rooted in dialogue with a specific community. They use both technological and non-technological tools to reveal how that community functions—socially and politically.

In the accompanying video, they use actual military technology to document landscapes that have been transformed by military testing and overtourism—issues that are pressing not only in Sardinia but also in Greece and now Cyprus. These are global patterns. But what made the project special was that they spent extended time in Sardinia, meeting with local craftspeople who were traditionally making rugs with pastoral imagery and age-old patterns. Together, they developed a new visual language—creating a 'war rug' using traditional methods.

Textiles have always functioned as tools of communication—they carry tradition, but also convey values, memory, and lived experience. That’s what made this aspect of the work so beautiful and important. The video installation is visually stunning, and their use of technology is clearly masterful in showing geological and topographic transformations. But pairing that with something so collaborative, simple, and handmade, yet equally powerful in its message, is really brilliant. It speaks to how thoughtful and attentive they are to the lived experiences of the communities they engage with. I was genuinely excited when they suggested including the rugs.

There is a notable return to the practice of making, particularly through handwork, as many artists are rekindling this connection. Why is working with hands important, and why are so many artists returning to it? What is the deeper meaning behind this?

There are a few ways of looking at it. In the larger art world—particularly in the U.S. and Western Europe—there's definitely been a growing recognition of craft traditions over the past 10 to 15 years. But for many artists, these practices have always been part of their work. For example, at the New Museum we recently organized exhibitions with Judy Chicago and Faith Ringgold, two American artists who have engaged with craft from feminist and African American perspectives going back to the 1960s. So it's not new—but there’s a renewed interest in elevating artists who were historically overlooked, and re-evaluating the role of craft in contemporary art.

Here in Greece—and across many parts of the Mediterranean—craft traditions like ceramics and textiles are much more integrated into everyday life. You see it not only in historical artifacts but in living practices: people still make ceramics, weave textiles, and carry forward these techniques. That changes the context. I think artists here are drawing on those traditions not simply to preserve them, but to push them forward—often in non-traditional, experimental, and highly political ways.

Take someone like Eleni Odysseos, a brilliant painter from Cyprus. She works with raw silk and jute—materials that are deeply connected to the island’s past. Silk refers to an industry that’s vanished from Cyprus. Jute is tied to potato farming, another disappearing economic activity. So her choice of materials isn’t just about aesthetics or tradition; it's about labor, memory, and ecology. It’s a commentary on disappearing industries and a vanishing connection to the land. By painting on these surfaces, she makes us reflect on what it means to use natural materials from a place where that very material culture is fading.

So yes, craft is part of the conversation—but it’s not just about reviving the past. It’s about how artists relate to materials, to land, to labor, and to lived history. That’s why I find it so exciting to see how these artists—especially here and in Cyprus—engage with those ideas in ways that are layered, rigorous, and deeply personal.

Installation view, In a Bright Green Field

Benaki Museum, Athens (June 11–September 13, 2025)

Photo: Giorgos Sfakianakis

Also, the beeswax shirts by Maria Louizou...

Beeswax—yes, beautiful. And that’s also part of it—those works are very skillfully made, but they’re also very contemporary. Maria works a lot with performance and dance, so while the objects aren’t used directly, they suggest a kind of use value. Beeswax is also a very ancient material—fragile, yet capable of lasting an indeterminate amount of time. I think having that sensitivity to the history of a material, and using it in new and surprising ways, is always exciting to see. And this was something she hadn’t done before—she had just started working with that material. That’s also what’s exciting about the show: giving an artist the opportunity to follow a train of thought, to explore a new idea. When you give them a good platform to present something like that, you often see some of the best work an artist produces. So it was really wonderful to see how many of them chose to take that chance and do something a bit beyond what they had tried before.

Installation view, In a Bright Green Field

Benaki Museum, Athens (June 11–September 13, 2025)

Photos: Giorgos Sfakianakis

I think that, compared to the previous shows—The Equilibrists (2016) and The Same River Twice (2019)—the word or notion that emerged most strongly from this exhibition is community.

Yeah, I think it’s a different way. So, you know, this is the third show. The first one was in 2016, which was, again, about young Greek and Cypriot artists. The second one, in 2019, was one that I didn’t curate—it was curated by my colleagues Margot Norton and Natalie Bell—and it wasn’t just about young artists; it included artists of any age, but only those based in Athens. So it was really about how the community in Athens had changed in recent years. There were even artists in that show who were no longer living, so it gave a kind of different picture of community.

I think, as much as this current one is also a show about younger artists, a kind of intergenerational dialogue is really important to what’s happening in both Greece and Cyprus. And that plays out in the show in different ways. So, you have someone like Theodoulos Polyviou, the artist from Cyprus with the fiberglass architectural molds—those come from a dialogue he has with a man in Nicosia who makes all of the decorative elements for churches in Cyprus. Their work is very different, their worldviews are very different, but there's a shared attempt to create an archive of that knowledge and history.

Or take Konstanza Kapsali’s film “Elsa and Olga”, with the two older women who swim every day. That’s a casual, unstructured kind of community that emerges in space and amidst the landscape, and Konstanza is invited into that community through the generosity of these women.

So, I think community is always an important theme. What’s interesting is how different artists at this moment are choosing to highlight it in different ways. Those are maybe more direct examples. But even, you know, Vera Chotzoglou’s film about the queer community here in Athens and how they’ve experienced the changes in the economy over the past few years—that’s a really important perspective. It presents an alternative to just thinking that everything is amazing and wonderful and that there's a boom happening. There are also challenges here, and the landscape is changing in ways that someone like me—who comes maybe once a year—won’t experience the same way as someone who’s living here every day and navigating different pressures.

So yeah, all those ideas about community are really interesting to me. And to see them showing up in painting, in digital work, and in projects that are more directly socially engaged—it’s a really exciting and fascinating trend for this moment.

Installation view, In a Bright Green Field

Benaki Museum, Athens (June 11–September 13, 2025)

Photo: Giorgos Sfakianakis

It is also fascinating how Sofia Rozaki blurs the line between the real and the surreal, combining personal and collective experiences to speak about alternative narratives surrounding the body, gender, memory, trauma, and sexuality.

I think, you know, imagined community is such an important thing—thinking about an expansive community. It feels even more vital at a moment when, certainly in the US but also in many other places around the world, people are trying to fracture communities and make them smaller and more exclusive. So, to approach that in Sofia’s way—with this kind of exuberant, surreal vision where communities can extend beyond gender, or even beyond species, or across history—is really powerful.

She’s creating community with historical figures from the past in those paintings, and it’s a beautiful, expansive, and genuinely utopian way of looking at the world. I think that kind of thinking is deeply needed to counter the more cynical and reductive ideas about who belongs in a place, which we see playing out elsewhere.

And then, you know, even Teo Triantafyllidis’s digital work—it’s this imagined community of machines and biological organisms working together to restore an environment. I think that’s also a really interesting way to think about community. Digital work is often seen as detached from those issues, or somehow blind to them, but Teo’s work uses technology to imagine possible worlds that are beautiful and expansive, and that explore how relationships—of all kinds—can form and be sustained.

Installation view, In a Bright Green Field

Benaki Museum, Athens (June 11–September 13, 2025)

Photo: Giorgos Sfakianakis

I really like the metaphorical title of Byron Kalomamas's work, If you want to know about change, first look at the rivers. It makes me wonder—where should we look to understand change? What is your opinion?

That’s a very, very tough question at this moment, because the change we’re seeing often feels quite destructive—and goes against some of the values we’re talking about. One of the hardest things, in conversations I’ve had with artists, is hearing how many of them are struggling with the idea of making art right now—given what’s happening not only in their own countries but also in other places very close to them.

But if I do have hope, it comes from these artists. I think that if change is possible, it’s going to come from the imagination of a better future. That’s what I find so inspiring—these artists are not only incredibly politically active—protesting, organizing, engaging directly with what’s happening—but what they create is also a kind of bulwark against hopelessness.

It’s a call to a more humanist relationship with the world. And that’s where I think real change can come from: an imaginative, hopeful view of the future. As much as we have hard work to do on the ground, I think we won’t succeed unless we also hold on to the hope for the community and future we want to build.

Installation view, In a Bright Green Field

Benaki Museum, Athens (June 11–September 13, 2025)

Photo: Giorgos Sfakianakis

Do you see the role of the curator also changing these days?

I think it's changing everywhere. I’ve been working in museums for more than 23 years now, and yes, the role of the curator has changed. But also, the role of the museum has changed. There’s much more interest in contemporary art. You might imagine that in New York everything is happening—but in many ways, New York can actually be quite provincial. Museums there don’t always pay attention to what’s happening in the rest of the world.

That, too, has started to shift during the time I’ve been working in New York. Now, most museums here are much more engaged with international artistic dialogues. So I think the curator’s role has had to evolve with that.

I started my career at the Whitney, and I love the Whitney—I still do in many ways. But its focus on American art, which is its historical mission, becomes more complicated when working with contemporary art. That distinction doesn’t hold as much weight anymore. Certainly, if you’re an artist working in America, you’re influenced by what’s happening around you—but as the artists in this show demonstrate, those dialogues are much broader. They’re more generative of new work and ideas the more they connect to conversations happening beyond their immediate scene.

So as a curator, you really have to be more attentive and open to what’s happening around the world.

At the same time, institutions are facing new challenges. European museums are dealing with reduced government funding—something American institutions have been grappling with for years. And in general, there’s just less funding and rising costs. So, we have to think more creatively about where to direct our resources. That’s become part of the process.

When I first started as a curator, you already had to think about budgets. It was never just about doing whatever show you wanted—you always had to ask, given the resources you have, what kind of exhibition will make the most impact? How can we imagine different kinds of collaborations that allow more to happen, even within economic and political constraints?

I think that’s true across the board—there’s no job that isn’t affected by what’s happening in the world. But especially for curators working in contemporary art, you have to be creative, collaborative, and sensitive. And the best part of it is having discussions with artists—seeing how people are doing things differently here versus elsewhere—and finding ways to share that through whatever knowledge, resources, and platforms we have in the museum.

***

In a Bright Green Field is on view at the Benaki museum in Athens from June 11 till September 13, 2025

Participating Artists: Niki Analyti, Raissa Angeli, Ileana Arnaoutou, Vera Chotzoglou, Anna Housiada, Danae Io, Byron Kalomamas, Konstanza Kapsali, Ismene King, Kyriakos Kyriakides, Latent Community ( Ionian Bisai & Sotiris Tsiganos), Ioanna Limniou, Maria Louizou, Marietta Mavrokordatou, Polina Miliou, Eleni Odysseos, Nefeli Papadimouli, Theodoulos Polyviou, Sofia Rozaki, Despina Sanida Crezia, David Sampethai, Marios Stamatis, The Post Collective (Mirra Markhaëva & Elli Vassalou), Theo Triantafyllidis, Maria Toumazou, Marina Xenofontos, Damianos Zisimou

Title image: Gary Carrion-Murayari. Photo by Christine Rivera