Soft fabric frozen in shape

Elīza Ramza

An interview with Estonian artist Rebeka Vaino

This week, Estonian artist Rebeka Vaino opens her first solo show in Paris – Honey en Route [21.10.–02.11.] in nomaadgalerie (9, rue Commines 75003 Paris). Rebeka’s practice is process- based and encompasses painting, sculpture, performance often blending together into in-situ installations.

In Honey en route she presents a series of “frozen knit” – ambiguous forms that weave together personal and collective experience, synthetic and natural materials and opposing binaries, creating webs reflecting the complexity of human existence.

Last summer she graduated from Goldsmiths, University of London and has just moved back to Paris.

We caught up with her a week before the opening of Honey en Route to talk about what has shaped her in these past hectic years of studying, moving around and dealing with navigating the anxieties of contemporary life.

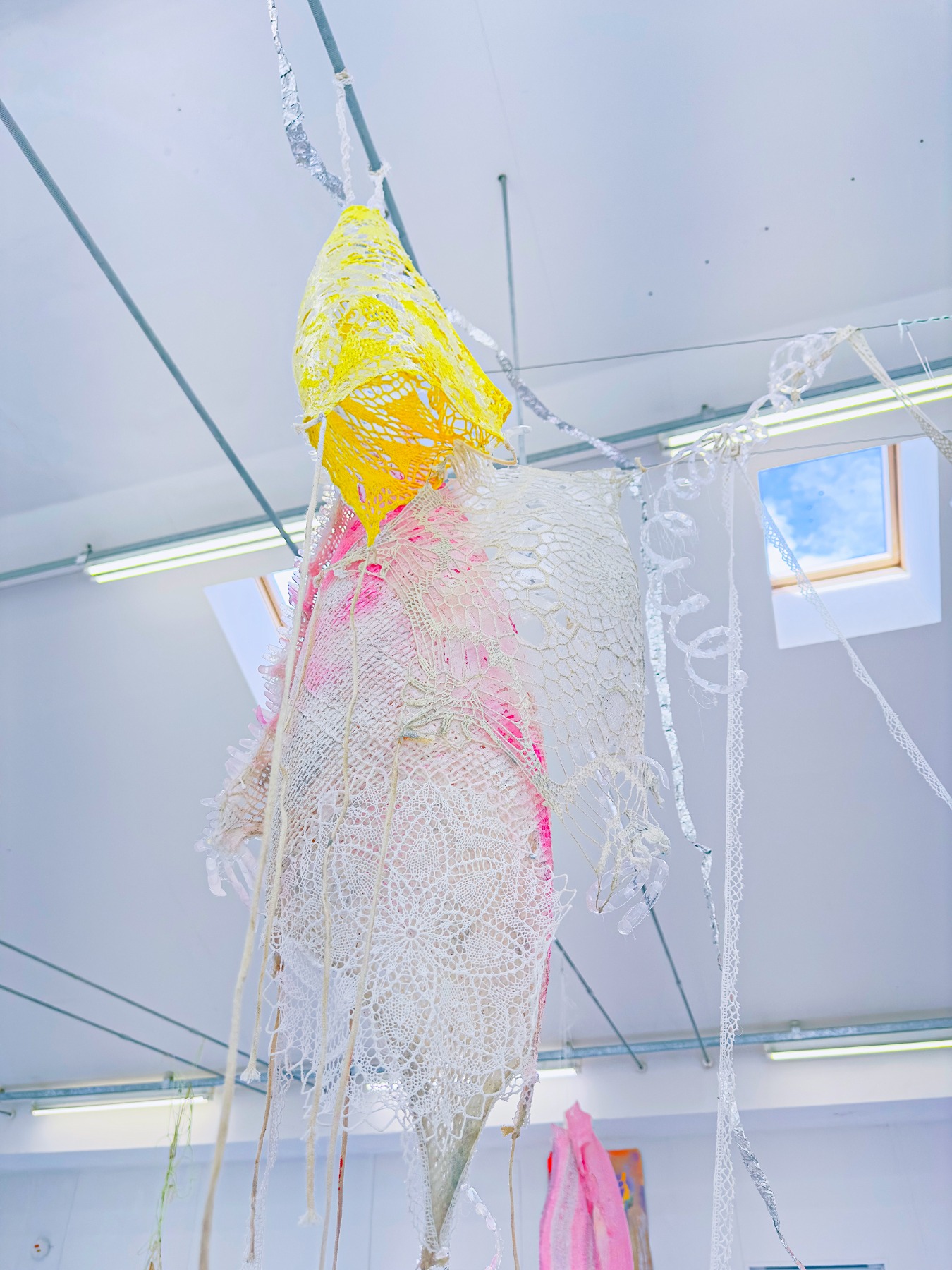

Detail of “Oh beautiful moment, please remain” from exhibition “A Portable Paradise: What would you pack in your case of emergency kit?”, Goldsmiths University, London, England, 2024. Personal archive

It feels like your practice lately has embarked on a re-discovery of your roots. Let’s start with two of Your installations for Goldsmiths graduation show last year - that was genesis of knitted sculptures. I have never heard it from Western European, but in Latvia in school we had this class literally called “housekeeping”, it was very gendered, I hope it has changed today as girls are drilling and hammering the art world pretty hard today (both laughs), was it also mandatory for you? How did you learn it?

Yes, it was the same for us – the boys did like woodwork and then the girls did the knitting, sewing and all these things. Then I was always such a tomboy, I didn’t care and never went to that class and I never really fully figured it out then. When I had to submit something at the end of the year, it was my grandmother who helped me pass the class so I learned many tips and tricks from her.

The beauty of passing on a skill to the next generation feels like something fading as a practice, but what brought you back to knitting after all these years?

A lot of the work I think is informed by everything that’s happened, I guess in the past 3 years, both in the world and in my personal life. Even before I went to Goldsmiths, the occupation of Ukraine started, which was a turning point I think for everyone from our region.

I took up knitting again, without any sculpting in mind, quite the opposite – to escape the constant thinking about work, war and to just soothe my anxiety. Through having to relearn all these knits, remembering what my grandmother had taught me became a way of reconnecting with my roots and more traditional heritage of Estonian pagan culture, I could say. But it started as this physical necessity to just calm down the nerves.

In Estonia during preparation for performance “The World Is Spinning Too Fast, I Need

Something To Hold On To”, Goldsmiths University, London, England, 2024. Personal archive

I found it interesting also because objects and activities associated with childhood become more precious and relevant when our mind and mental stability is threatened - we tend to return back to the core. Part of your graduation show featured a Soviet era carpet cleaning structure – which all of us who grew up in Soviet block houses remember as something that, in a child’s eyes, simply begged to be climbed and conquered. You repurposed it in your performance The World Is Spinning Too Fast, I Need Something To Hold On To, how did that come about?

Yes, it’s exactly as you said – there was this uncertainty happening both in the world and in my personal life and so you are drawn back to the time, moments or objects that make you feel safe and remind you of a simpler time or a happier time. Knitting was one of them for me, and then I noticed it was turning into something more than just a calming process.

I was also painting a lot at the time, on loose canvas, and started wondering how I could exhibit those works. Around then, I discovered pole dance, as a hobby next to knitting, which was already turning into work, and somehow, subconsciously, thinking about our post-soviet childhood days led me to the carpet-cleaning structure. At first, I only saw it as a shape to hang my paintings on.

Eventually, I realized I’d probably have to make it myself since there weren’t any like it in London and it wasn’t exactly possible to take one from public space in Estonia and ship it over (laughs). At first, I began “travelling” through Google maps - some of them have been replaced by really fancy ones, but the one in front of grandmother’s old house is still standing, exactly the same one I used to climb on as a child. I got this old soviet blueprint from the National Archives of Estonia for the structure and eventually built an exact replica in London. Repurposing, reconquering – relating to this object in a completely different way, coming back to it with new skills to climb it.

Funny enough, the diameter of the dance pole is actually almost identical to that of the carpet- cleaning frame. So I could see what was happening and started to train on the pole with the idea of the structure in mind.

I realized there was no real difference between what I do on the pole or what I could do on the carpet cleaning frame and what the sculptures themselves do in space. The sculptures twist and turn in the same way that I twist and turn – we are all fragments of those knitted webs.

So the need to hold on to something or to protect something – in the end, it’s all the same. The world is spinning too fast and you need something to hold on to.

Close-up from from exhibition “A Portable Paradise: What would you pack in your case of emergency kit?”, Goldsmiths University, London, England, 2024. Personal archive

Yes, I really enjoy that analogy of the protectiveness that evolved around knitted works which were present in your other installation at Goldsmith A Portable Paradise: What would you pack in your case of emergency kit? and now appears in a more extended form in the Paris exhibition. Those were the beginnings of cocoon-like sculptures.

At the time when I was preparing for the Goldsmiths degree show, Estonian households started to receive these leaflets, probably in Latvia, too, literally instructing people on what to pack into emergency bags “in case it happens” and you know it hit deep because we all understood what it could mean. As I’d been living abroad for quite a while, each time visiting got me on this sorrowful note – of course, we can have these practical emergency kits prepared, but what does this survival mean if you can’t bring with you the things that actually make life worth living? Those irreplaceable things that hold warm memories – the essence of feeling home, the soul’s survival kits, like the beach and the trees around my summer house – settings you cannot evacuate physically. So if I just could lay down this great net and pack the special places with me.

That’s when portable paradises were born as these gridded, knitted cocoons that carry all the fundamental souvenirs. There is also this poem by Roger Robinson A portable paradise, where he describes this necessity of carrying your grandmothers’ green hills in your pocket to look at them for a sense of fresh hope. But it all came together when I asked my mom to bring me some sand from our summer house for one artwork and she literally brought me a handful of sand in this pocket-size baggie, like a drug baggie – which also is a touching metaphor. So that was the starting point for pretty much everything that made me realize that maybe I can bring the beach with me.

Exhibition view. “Honey en route” at the nomaadgalerie, Paris. Photo: Juan Garcia Couder

It reminds me of Nicolas Bourriaud altermodern manifesto, where he described culture becoming portable, and artists as “homo viator”, contemporary traveller. Mobility gives rise to new “journey-forms” passing through signs and formats, made of lines drawn in space and time, materializing trajectories rather than destination. Your being on the road art practice feels like part of this movement.

In so many layers… The traditional patterns of crochets and knitting, using all these natural yarns already carry embedded folklore and culture of Estonia and Baltic region in general. Knitting itself happens all around Europe while being on the road to the next destination.

Also they are a form of time keeping and energy channeling. On a third level, the formal quality itself - even gauze to keep the scars protected is a delicate grid or when making casts, fiberglass grid holds everything together. It has these protective qualities. So all the layers piling up created that metaphysical portability.

Close up from exhibition “Honey en route” at the nomaadgalerie, Paris. Photo: Juan Garcia Couder

You mentioned timekeeping - they could be shapes of time, making the passage of time palpable – would you agree?

Absolutely, you know in London, compared with Paris, it takes so much time to just move around the city from point A to B. On the tube, there is often no internet connection so over time I learned to measure my daily routes in rows of knots. One row equals one stop on the overground for example. It’s similar to hair or making of yarn - memories are stored in that repetitive movement of expanding.

“Changeling” from group show “Embodement in nature”, 2025, Othelandz, London, England. Personal archive

You do translate these universal human existence enigmas into sensual language spoken by materials. Besides knits and paintings, which you aptly call - sculpted canvas, in your sculptural work horsehairs are often used, snakeskin, beeswax now horseshoe is entering the scene – how did you choose the medium you work with?

I guess you can never really separate yourself from where you come from and from your lived experience. I presume for many people from our region – part of our strength lies in the ability to build or create things out of seeming nothingness, to build a house ourselves. I think grooving up in the Baltics ingrained recycling as something natural and obvious, you just wouldn’t throw things away so easily. Of course, it reflects perspective shaped by modest economic conditions, but it also gave me a skill of reimagining objects and their purposes. Most of the time it’s not even conscious, but it has deeply formed how I approach my practice.

I grew up around horses and we still take care of some on and off in my summer house so just from combing their tails, I came across the qualities of horse hair. For Honey en Route show I used them for embroidered drawings, their characteristic elasticity forms patterns similar to the tiny fences around flower beds in the Luxembourg Gardens – a place where I spent countless days during COVID. What I want to say is most of the time it comes together as an unconscious collage, I do like the surrealist idea of psychic automatism: I don’t preformulate, I try to follow intuition without overthinking. That isn’t always easy – to perceive these archetypal codes that are all around us. And of course it’s influenced by so many factors – like working with beeswax just came from a nomad lifestyle where you wouldn’t use something as toxic as polyester resin in your bedroom studio.

Definitely being brought up in a place where we didn’t have his excessive consumption possibility has formed my choosing compass – if you grow up with warmest socks knitted by your grandmother it implants a sense of safety, peace of mind and warmth of home. And snakes – my ex-partner has snakes so observing them shading their skin gave me a sense of lived life, like patterns of existence, the same goes for honey. All of these materials carry embedded histories and memories that inform the work.

Speaking of bees, I think it was at least 10 years ago when the first wave of concerns about endangered bees began and all the research started to fill the news - how crucial they are as pollinators for our food chain and how ecosystems could collapse if they disappeared. I did look it up again and it is fascinating, the story of their colonies, a system run by females with such a profound web of relationships, which again is an invisible structure that plays a more important role in our lives than we might imagine.

Yes, there is also a strong sense of community. That brings me to another aspect that just clicked in our way of title choice for the exhibition. At the beginning of 20th century and through the First World war in Paris, there was this artist’s kind of residency, kind of shelter – that hosted many Eastern Europeans, Jews, also many important Estonian artists like Konrad Mägi and Nikolai Triik as well as Soudine, Zadkine were there. It was called La Ruche – The Beehive. The building still exists and its form evokes the structure of a beehive. I’m of course grateful and feeling lucky that we are here because of choice, but reading about it brings the admiration of the artist’s supportive systems and the history that I share with these previous artists in this town.

Exhibition view. “Honey en route” at the nomaadgalerie, Paris. Photo: Juan Garcia Couder

Can you tell more about what led to the title of the show in Paris, Honey en route? – en route in french means “on the road”, “during the journey”.

First of all, of course, it comes from the way that the works are made – the most time consuming part of the process is the actual knitting. It accompanies me everywhere I go. The past years have been in constant moving that escalated this summer with partly leaving London and moving my studio to Estonia and now in autumn moving all my life back to live in Paris again. In the meantime, visiting close friends in Italy and South of France. So this all made me wonder what does home mean finally? And what if my state of home really is being on the road?

The honey comes from this idea of a honey tree (mesipuu), which is an important symbol in Estonian culture representing freedom. There is a song by Juhan Liiv “Ta lendab mesipuu poole” ((s)he flies towards the honey tree) which is one of the most important songs that we sing at the singing festival, which is a major tradition in Estonia and as you said also in Latvia – where people come together once every five years. In Estonia it happened this summer and I was living in Estonia for a few months in the summer, which hadn’t happened for a long time, so I went to the festival and that song and the analogy of honey tree and us as bees just allured me and stuck with me as I was thinking about and making the work for the show.

Honey has a very rich symbolic heritage in many cultures. The coating layers of your knit sculptures have a visual similarity to honey. Some of them are bee-wax coated, others in resin or latex. Your practice seems full of these polarities between natural and artificial – mohair yarn with resin, appearing soft and fragile like frost flowers, yet mostly firm.

“Catharsis” [2025, crochet, beeswax] from exhibition “Honey en route” at the nomaadgalerie, Paris. Photo: Juan Garcia Couder

Yes, some of the works are a bit more rigid than others, and some are slightly more pliable depending on whether I use acrylic, latex or resin. But when force is applied, they can withstand that. They keep their shape, bending without breaking – like a boat out in a stormy sea, able to sway here and there, yet emerge strong. That’s the quality that I really like about them. They remind me of soft fabric frozen in shape.

Yes, the ability to withstand storms is what we as individuals need - to survive without breaking under the pressures, like waves come over us nowadays.

Exactly. How to stand your ground without braking, being flexible, being resilient – I guess that’s how Baltic people have got through all the mess. The singing revolutions, which can sound a bit absurd – fighting with singing – but there is that softness that makes you incredibly strong. We will never have the strongest military of all of the world, but that’s not the only thing that you need. Sometimes you do need to just keep going. Singing probably maintains the sense of togetherness and belonging, there is something magic in ways of resilience.

Multiple “Le Galop Crescendo” from exhibition “Honey en route” at the

nomaadgalerie, Paris. Photo: Juan Garcia Couder

Speaking of magic, it seems that spiritual ideas are increasingly shaping society’s perception of reality. That brings me to the horseshoe multiples You are presenting in Honey en Route, could You tell me how they came along?

I was listening to this podcast and researching work by Marcel Duchamp and I got carried away with the idea of La boite en valise. His situation of course was different since he needed to flee Paris, that’s what powered the idea behind those artworks – sort of little museums presented in luggage cases. But still I’m aware that my large scale sculptures not everybody can afford, even if it’s not the financial issue – You need space for them, much more than for a wall hanged work. Reflecting around this “on the road” concept – which actually many culture scene professionals experience constantly, I wanted to offer something more accessible, more tangible, something that viewers can take with them besides memories and pictures. I decided to start a series of multiples in the form of horseshoes. In pagan cultures horseshoes symbolize good luck. Traditionally, they are hung over the doorways, though there is a debate about which way they should face, ultimately, that’s up to You. I was inspired by their form back in Estonia, but I thought it would be silly to take up weight in luggage. By chance, I came across one here in France, which I felt auspicious, as folklore says you should find it by chance. So hopefully that good luck carries on into the multiples. (laughs)

In the end I’m making 2 versions – one that you can put on your wall or above a door. And another with a carabiner to hook onto your belt or bag or however you want to carry it with you. It’s like a lucky charm, a portable talisman. These multiples continue the idea of turning to relics or pagan traditions, deeply embedded in collective consciousness. The horseshoes also continue the theme of protection, one of their symbolic forces.

Besides knitted sculptures and multiples, Honey en route includes paintings as well. Your painting practice involves working on canvas off-frame, forming sculptural configurations and fragments linked together. You call these sculpted canvas, how do they take shape, is it dismantling one piece or attaching many?

There are several reasons why I gave up using frames, but one reason I stuck with it is again travelling, not to leave them behind which would mean going into waste, something I hate. The desire of shaping canvas, cutting and forming it comes from the wish I had as a teenager – to become a fashion designer. I just realized I wasn’t interested in the fashion business, yet the creative side of that stayed. Sometimes a piece doesn’t go where I want it to, so I choose the freedom to just cut it up. It may seem destructive, but in that destruction there is creation. I never throw anything away; after some time, sometimes years, I can revisit these fragments and they make sense. Combining them allows new forms to emerge. So this approach relates to collage, transformation and portability. Nowadays I always have one suitcase that’s literally full of these rolled up pieces – fabrics and canvas. I guess there is a solace in being able to break, but also fix it. That you can put things back together again. It’s transformative, like the Tower collapsing card in tarot, followed by the Star, the card of hope. A phoenix rising from ashes. Experiencing trauma involves that horrible collapse, but bit by bit You will rebuild Yourself. That’s how a sculpted canvas emerges from piles of painting fragments. It all intervenes in transformation – death, rebirth, death, rebirth, death, rebirth. My take on making is this kind of a collaging, which is simultaneously creation and destruction. You can’t remove them from each other, at least I cannot. That’s why in Honey en Route the threads are highly present, they could be called a thread of life. I mean, it’s the same as people wanting to cut their hair after a significant event – the weight of experience is stored there. Everything is stored there.

“La route qui se merge” from exhibition “Honey en route” at the nomaadgalerie, Paris. Photo: Juan Garcia Couder

Title image: Rebeka Vaino at her solo show “Honey en route”, nomaadgalerie, Paris. Photo: Juan Garcia Couder