Traces That Remain

Sabīne Šnē

A conversation with the Latvian artist Konstantin Zhukov

The connections we share with one another and with places. And quieter ones within them, the ones that connect us to silenced histories, erased stories, untold memories. A conversation with Konstantin Zhukov (Konstantīns Žukovs), a Latvian artist whose practice unfolds in spaces where hidden intimacies gain visibility and marginalised queer histories are given room to breathe. His most recent solo exhibition, Black Carnation: Case Study No. 2, curated by Goh Wei Hao, was on view at outhouse gallery in London until December 15.

Zhukov’s research-based practice centers on recorded and oral histories that explore different forms of attachment and sexuality, drawing on sources ranging from the homoerotic poetry of the Islamic Golden Age to Oscar Wilde’s love letters and Michael Foucault’s writings on desire. His ongoing project Black Carnation brings together photography, installation and archival fragments to revisit the scarcely documented queer histories of twentieth-century Latvia.

Fifteen years ago, Zhukov moved from Riga, Latvia to London to study at Central Saint Martins and the London College of Communication. Today, he works between the two cities and has presented his work internationally through solo and group exhibitions and art book fairs in Latvia, the UK, Slovenia, Lithuania, France, Spain and China.

Black Carnation: Case Study No. 2, outhouse gallery, London, 2025

This conversation takes place while your solo exhibition is on view at outhouse gallery. How do queer histories from Latvia inhabit a gallery space in southeast London?

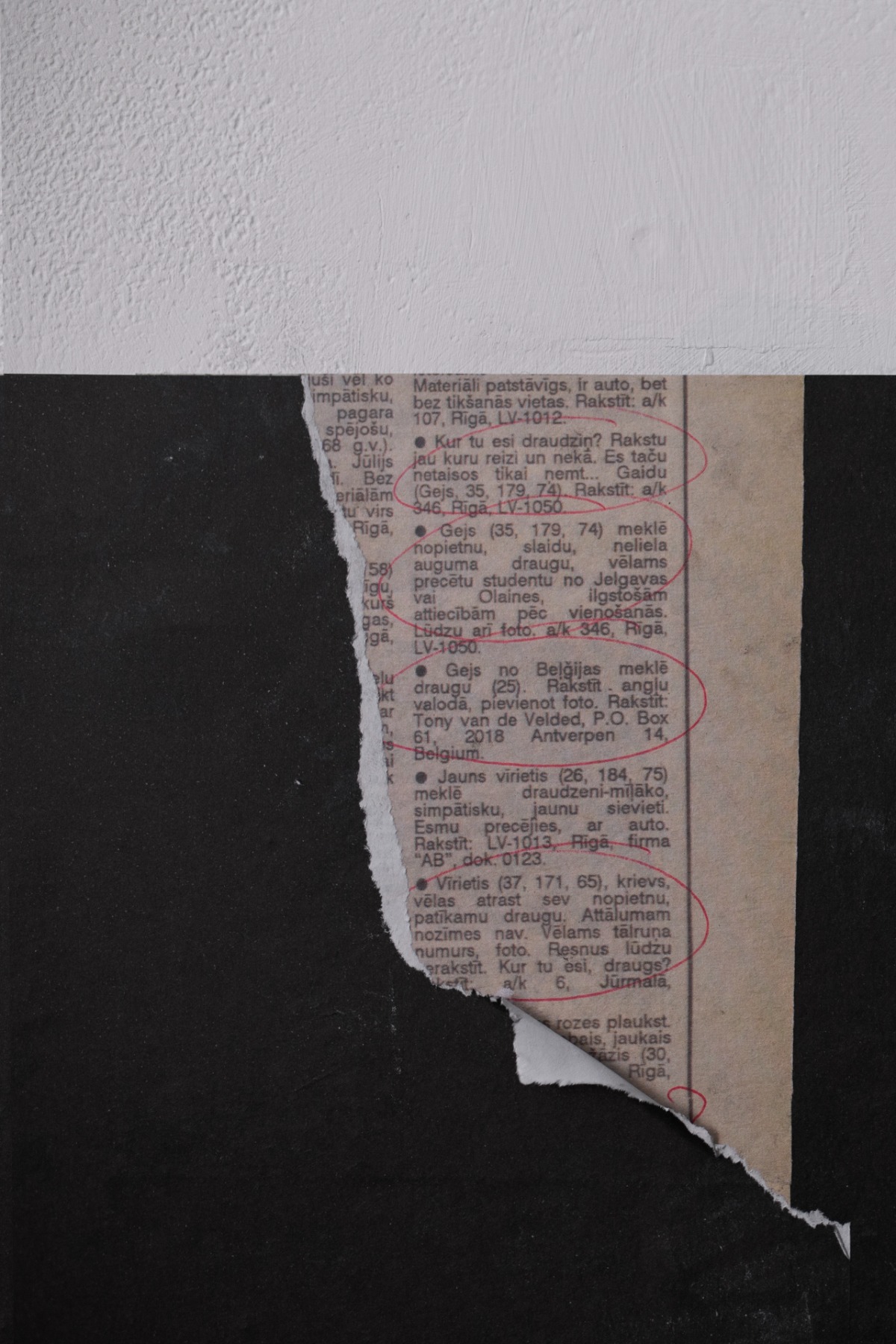

I am showing Black Carnation: Case Study No. 2, an installation that looks into the first gay parties organised in Riga straight after the independence from the Soviet Union and subsequent decriminalisation of homosexuality in the early 1990s. Drawing on conversations with the attendees of these parties I create a tableau of memories and impressions set against the historical background of newspaper clippings, same sex dating ads of the time mixed with my original and archival photography.

These semi-legal gatherings were organised in the basements, flats, and newly vacant factory spaces of quickly crumbling industries. In particular, my attention was drawn to the party organised in the Museum of Medicine. For decades, medicine was a tool of control and oppression of queer people, and suddenly a museum of this very discipline became an enabler of the newly found freedoms. As the curator Goh Wei Hao put it: ‘Surrounded by medical instruments once used to classify and pathologise queer bodies, partygoers transformed the museum into a site where they could experiment with touch and desire.’

I am very much interested in how people adapt spaces to their needs, shifting their meaning and function. That’s why it felt fitting to present this work in the outhouse gallery, a former Victorian public toilet. Now a white cube space, this building is typical of ones which would have lent itself to cottaging, or cruising, a space for seeking anonymous sex between men. A space within a space within a space…

Black Carnation: Case Study No. 2, outhouse gallery, London, 2025

By now, the Black Carnation project has evolved into several parts, or “cases,” as you call them. Why have you decided to show this particular one now?

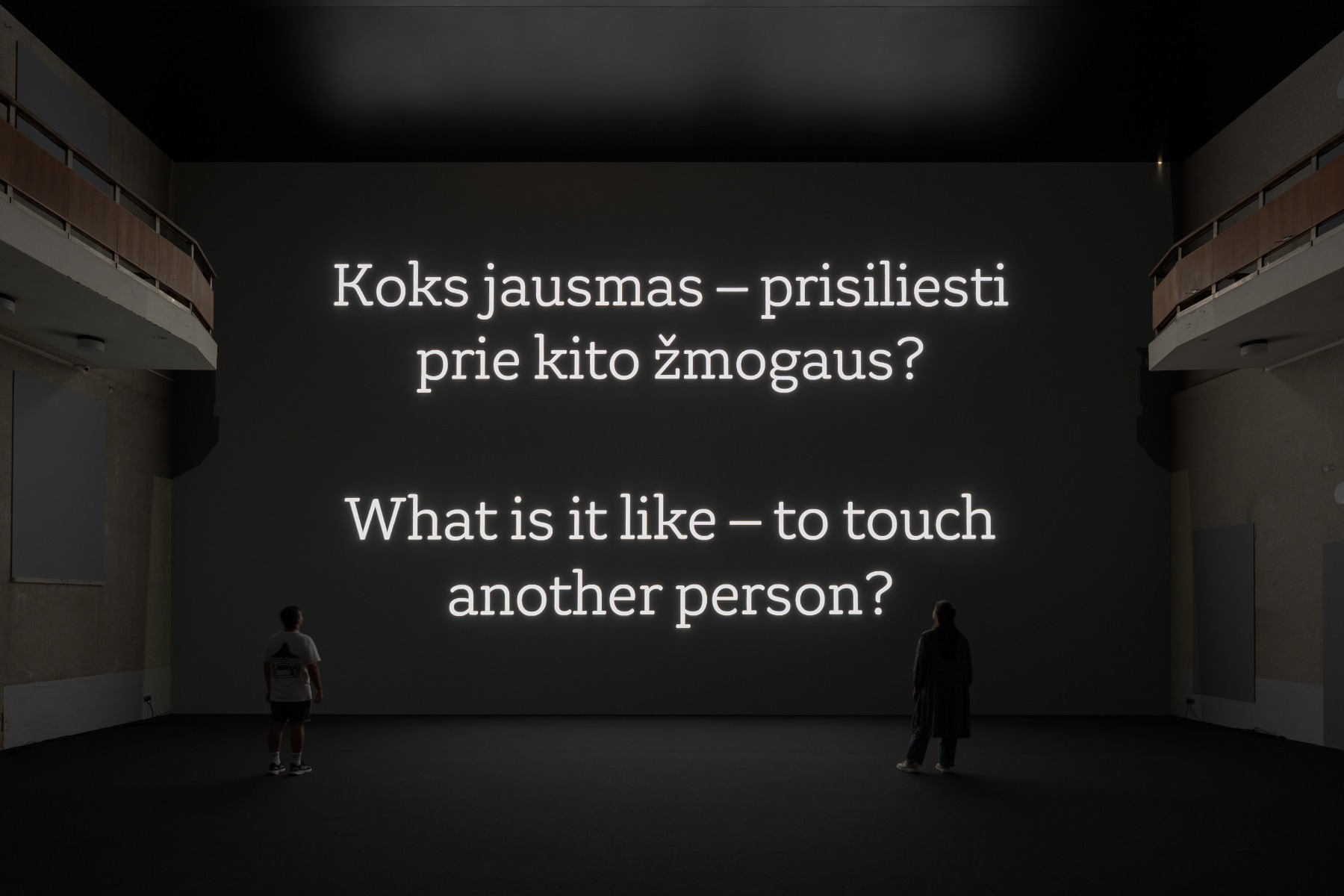

These parties are too fresh for the historians, but too old to be organically recorded on the Internet – I saw an opportunity to fill the gap. I feel like these stories represent an often unmentioned yet vital aspect of the broader liberation and freedom in the Baltic context. There is a common thread going through all the interviews – touch. Desire to touch, inability to touch, not knowing how to touch… But touch has a political potential too – think of the Baltic Way, a seminal protest action on the way to Latvia’s independence from the Soviet Union and subsequent freedoms it brought, including to dance and desire.

It is also my most complex project to date that involved many people – from the interviewees, a sound designer, research and production assistant to the people organising queer nightlife in Riga today who voiced-over the words of the original partygoers.

Black Carnation: Case Study No. 2, outhouse gallery, London, 2025

The experiences you explore in this work feel like the first cracks in the silence that once shaped public life in Riga. They offered a breath of fresh air after a Soviet occupation regime that forbade anything outside the accepted norm, anything that men in suits believed did not serve to build communism. How do you approach public and private spaces in your work?

Public versus private as well as outside versus inside are important themes in my work. In the previous iterations of the Black Carnation project, I have spoken of the inverted nature of public and private spaces in many Soviet queer life stories. Domestic spaces were often shared, so queer people had to look for intimacy outside and away from the neighbours’ watchful gaze – at a cruising beach or a public bathroom. In turn, in Case Study No. 2, exhibited at the outhouse gallery, the focus is on the inside versus outside. Speaking of the semi-legal underground parties and closeted lives of the 90s, I’ve left the gallery’s metallic shutters down (visitors enter through a side door), covered the walls with black wallpaper and papered the windows, leaving just one illuminated. A single flashing light and the muffled beat of a soundtrack leaking through the brick walls into the darkness of the public park outside.

And how do you deal with privacy and protect those who trust you with their stories?

Privacy is an integral part of my work. While many people are happy to be interviewed or photographed, some ask not to mention their names or professions, others request total confidentiality. I really do appreciate the trust of my subjects. I don’t take it for granted.

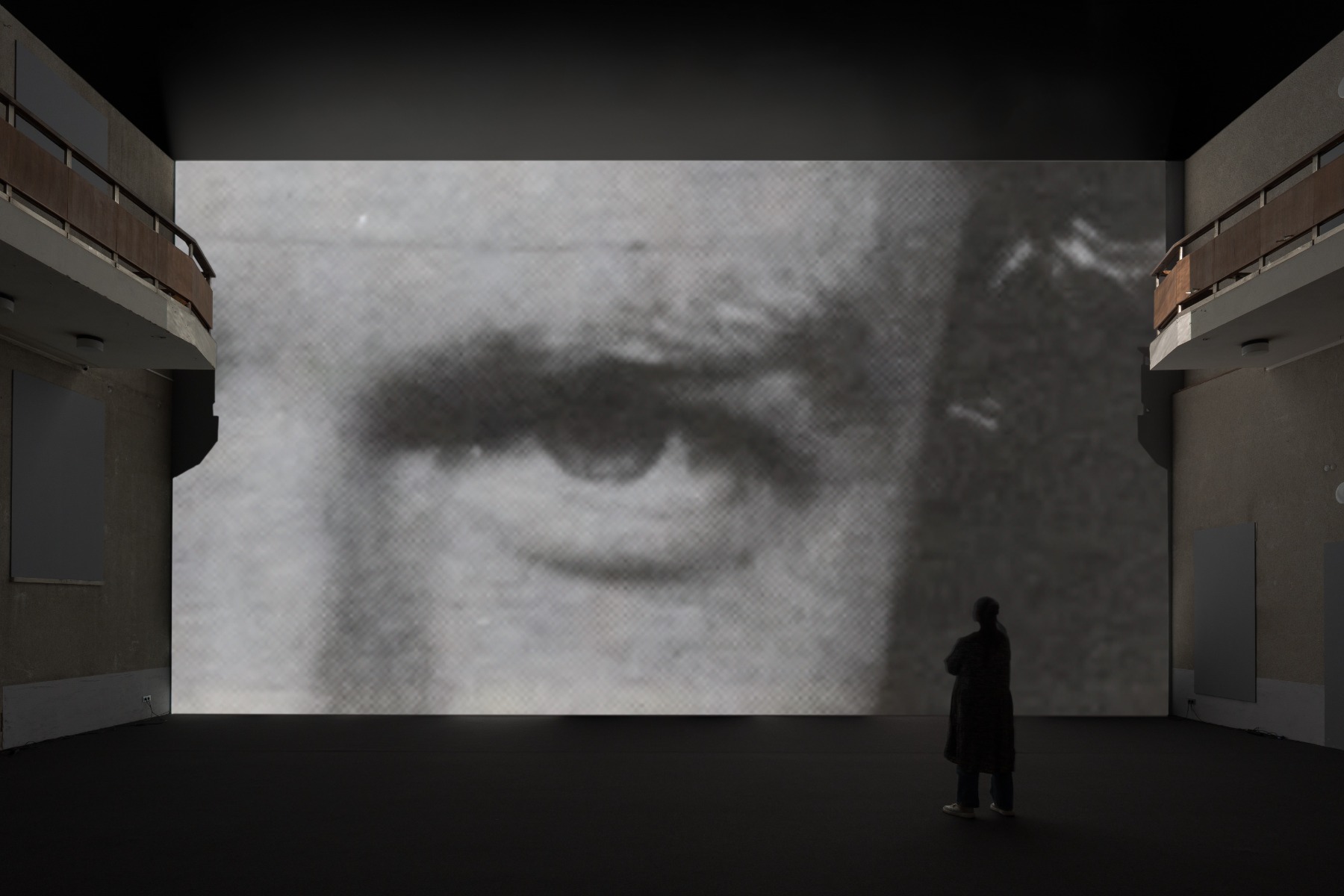

Banguoja audiofestival, Radvila Palace Museum of Art, Vilnius, 2025. Photo: Andrej Vasilenko

What first sparked the Black Carnation project? I imagine part of it came from a desire to fill gaps in social history, but there must also be more personal reasons, no?

I’ve started working with the historical texts dealing with same sex desire well before I turned to Latvian histories, and initially it did feel like a form of self therapy to accept my own sexuality. However, I’d say curiosity and wanting to celebrate the everyday human stories is the main drive for developing my work now.

Can we talk about the term “queer”? It carries many meanings, and people relate to it in different ways. I’m personally drawn to the idea of queer ecologies, which challenge binaries and celebrate diversity. Or anything connected to Derek Jarman’s gardening journey. What does queer mean to you?

For me, queer people are those who actively challenge the status quo, who are political, who are passionate about human rights and freedoms – it’s not just about who you sleep with. I always say that some of the queerest people I know are in the heterosexual relationships. I do see “queer” as a badge of honour.

Banguoja audiofestival, Radvila Palace Museum of Art, Vilnius, 2025. Photo: Andrej Vasilenko

If you don’t mind sharing, what have been some of the most surprising or affecting discoveries while exploring queer histories in Latvia?

Loneliness is a big part of it – a common thread going through the decades and many stories. But talking about the 90s parties, I do find the mafia thing the most telling. The club nights had to have a bouncer who could deal with a local mafia. Back in the 90s, every business in a post-Soviet country had to have a “roof”, a local mafia one had to pay for “protection”. Apparently, some of the party organisers knew someone from the presidential security service, so the bouncers to one of the gay nights were the same people that were guarding the country’s president! Isn’t it great!? It does show how messy, dangerous, yet exciting the 90s were.

When you transform archival material into artwork, how do you choose what remains from the original source and what to let go of?

Oh, editing is the hardest, isn’t it? It is always walking a tightrope – embracing the poetry of an artwork, developing a captivating story, while staying true to the sources. It’s a constant process.

Banguoja audiofestival, Radvila Palace Museum of Art, Vilnius, 2025. Photo: Andrej Vasilenko

Your practice spans various media. For your first solo exhibition at ISSP Gallery in Riga, you created a mixed-media installation combining photographs, found objects, bathroom tiles, a poem by Kārlis Vērdiņš and text from a Soviet-period health book. Last year, for your solo exhibition at NEVEN Gallery in London, you presented photographs alongside a folding Soviet bed frames that those from the former Eastern Bloc immediately recognized as a raskladushka. What guides your choice of medium? And what is your ongoing love story with photography, which seems to remain a constant throughout your work?

Photography is one of the most accessible and immediate mediums for both, a creator and a viewer. But photography is only one part of my work as I am always interested in the spaces they live in. How can I adapt and occupy a space to communicate my ideas? How can I transport a viewer somewhere else, immerse them in the stories I am trying to tell?

You are also self-publishing zines and catalogues.

As an artist, I’ve started off from making zines and taking part in the book art fairs. It’s an incredible way to meet people and talk – the number of references, reactions and feedback I’ve got from conversations at my self-publishing stall is invaluable! If you are in Paris during Paris Ass Book Fair at Palais de Tokyo – do go!

Black Carnation Part Two, ISSP Gallery, Riga, 2022. Photo: Ingus Bajārs

What responsibilities do you feel when working with queer histories? Because you are working with queer archive and by doing so, you are making one yourself, and you are showing that history and present contains queers.

I think we have to distinguish between artwork and a document. Through my research I do generate the historical records and I really do need to find time to prepare the transcripts of my many interviews for inclusion in the National Oral History Collection at the University of Latvia. However, in my art I strive to depart from “illustrating” the history, but use it as a starting point to ask an age-old question – what is it to be human? I do think that great art touches some strings within us that are hard to put a finger on, to describe or document. Hopefully one day I will succeed.

Black Carnation Part Three, Neven Gallery, London, 2024. Photo: Dominique Cro

Your work is politically and socially charged. It reminded me of a book I read a couple of years ago, Radical Intimacies by Sophie K Rosa, in which she explores different forms of intimacy, from family and self-care to friendships. In a chapter on sex, she argues that sexual relationships are shaped by the conditions of people’s lives, such as where they live, how much they have to work or whether they have access to contraception. She concludes that “who gets to experience pleasure is a political question.”

That reminds me of a guided tour of an exhibition at MO Museum by its co-curator Rebeka Põldsam. Standing in front of my work on Latvian cruising beaches she asked the tour visitors why women didn’t cruise? Well, perhaps, because women often feel unsafe just being outside…? I see it in my research too, there is a recurring absence of female voices when talking about Soviet queer experiences and it can still be difficult to get women to speak on record, even if anonymously.

Black Carnation Part Three, Neven Gallery, London, 2024. Photo: Dominique Cro

Having exhibited internationally, what differences have you noticed in how audiences in different countries engage with your work?

I feel because of Latvian communist past and preconceived conservatism of Eastern Europe, it is very easy to slide into a simplistic and frankly quite bland narrative of oppression when talking to the western audiences. But people are superbly inventive and have an amazing ability to adapt to the most dire of situations and find joy. Cruising, for example, can be viewed as a story of oppression or a story of resilience. I want to celebrate resilience!

You’ve called London home for many years. The current political climate, combined with the high cost of living and lack of arts funding, makes it hard to survive there as an artist. Materials, studio space, time, energy, it’s a constant hustle. What keeps you motivated to continue creating?

Curiosity.

It’s the end of the year, so it only feels appropriate to ask a question about your future plans. What’s on your agenda for next year?

Next is Paris – Circulation(s) photography festival in spring. Apart from that, I really need to get some proper studio time – there are so many more stories to tell!

***

Black Carnation: Case Study No. 2 was initially commissioned by the Latvian Centre for Contemporary Art (LCCA) for the contemporary art festival Survival Kit 15 in 2024. In spring 2025, it was shown at the Radvila Palace Museum of Art as part of the Banguoja audio festival in Vilnius.

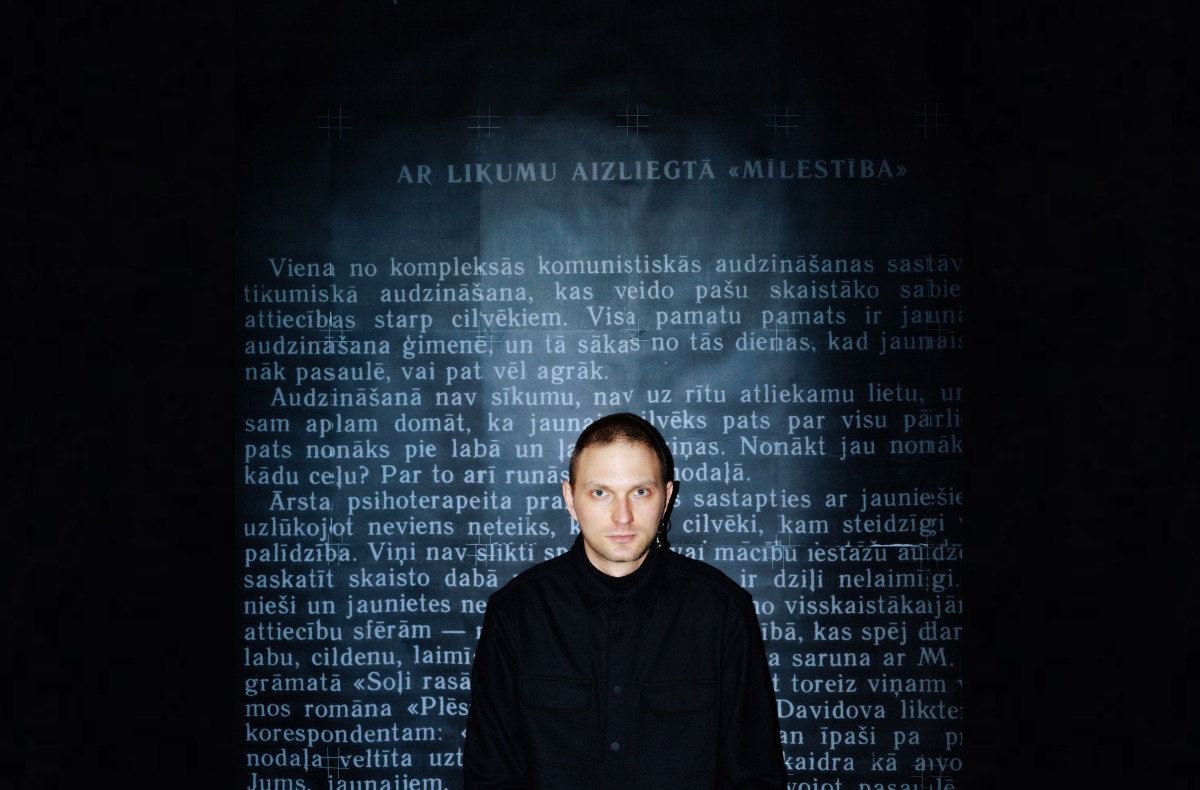

Title image: Konstantin Zhukov. Photo: Ģirts Raģelis