A knife, an axe, and a piece of firewood

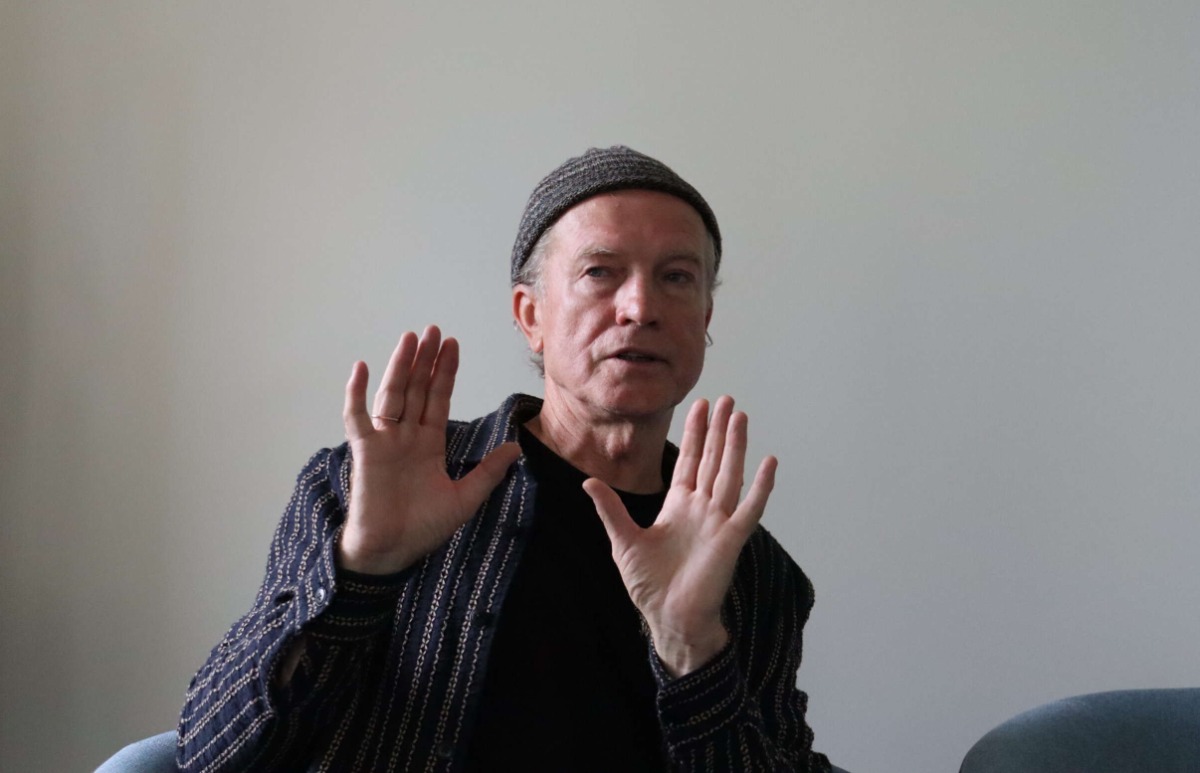

A conversation with artist Andris Breže

The exhibition by Latvian artist Andris Breže will be on view at the Riga Contemporary Art Space in Riga from February 6 until April 5, 2026. This exhibition is the first event in the series Milži (Giants), which is dedicated to significant figures in the history of Latvian contemporary art. The exhibition features works of art that characterize the cultural landscape of their time. The cycle is characterized by an archaeological approach, i.e., searching for fragments that have been forgotten or lost somewhere. These “lost classics” comprise a story not only about art history, but also about the times and events of that period. The artworks on display in Milži have been sourced from the collections of the Latvian National Museum of Art and the Latvian Museum of Contemporary Art, private collections, artists’ studios, attics and basements, while some have been lost to eternity. Opportunities to see them are few and far apart.

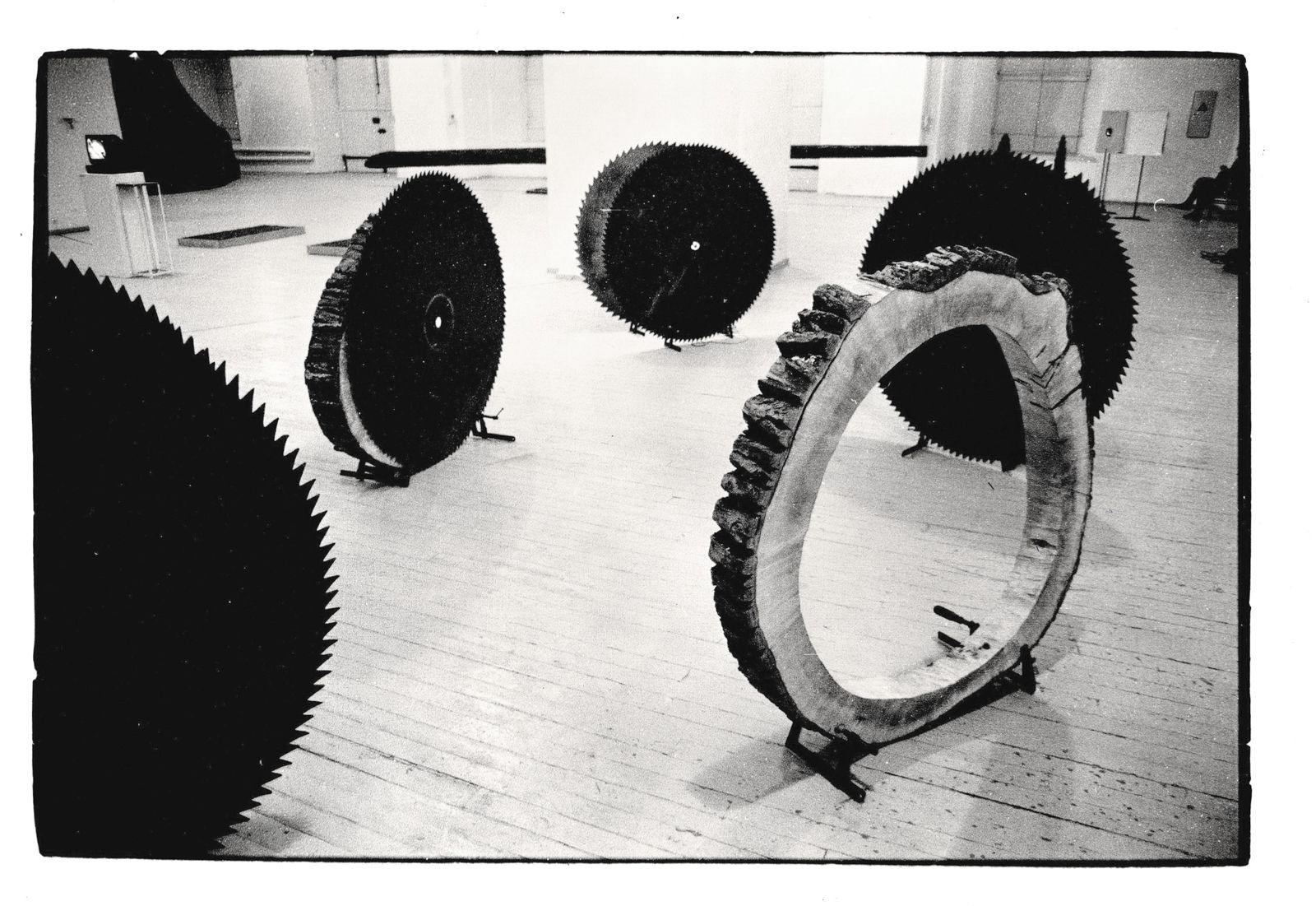

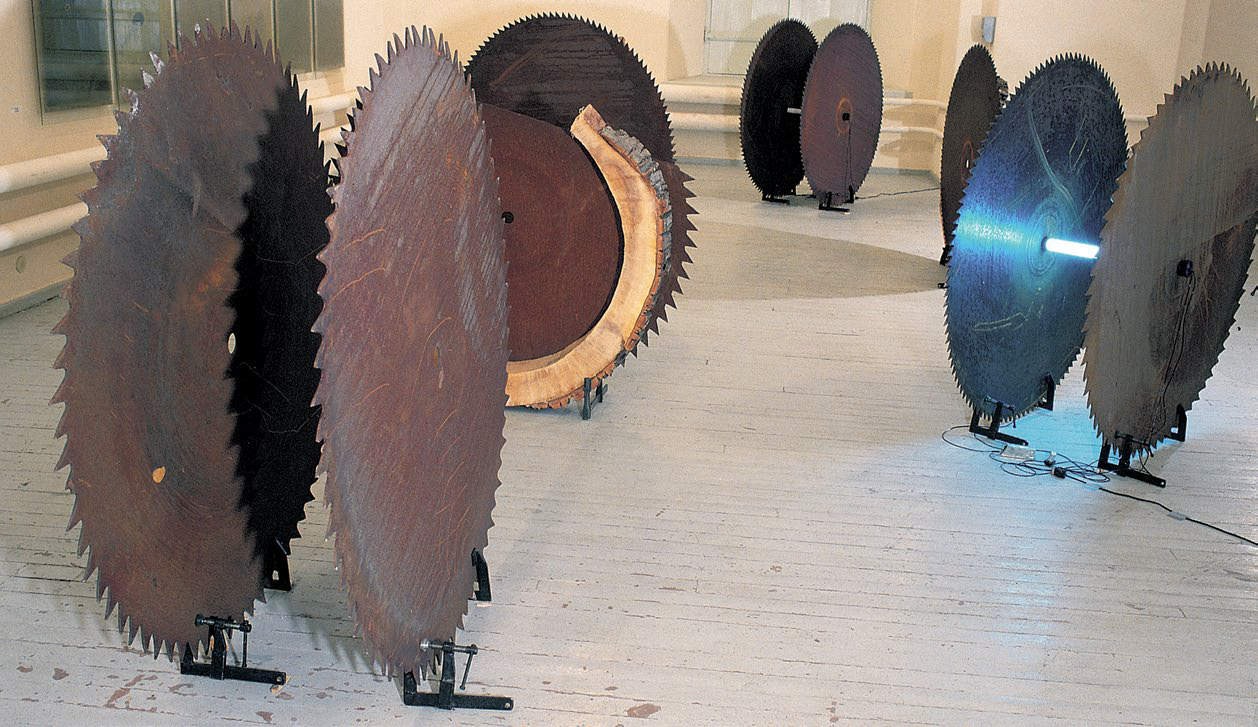

Andris Breže’s object Aploks (Enclosure) was exhibited in 1994 at the Soros Contemporary Art Center’s annual exhibition Valsts (The State), curated by Ivars Runkovskis, which was held at the Arsenāls exhibition hall.

The starting point for this exhibition at the Riga Contemporary Art Space is your work Aploks, which was exhibited at the Arsenāls exhibition hall as part of the Soros Contemporary Art Center’s annual exhibition Valsts (curated by Ivars Runkovskis). It’s a rather impressively sized composition consisting of rough wooden tree rings and ripsaw blades.

Anything that we express...comes from our very beginnings. How you grew up, how you developed, what your childhood was like, what you did back then. This is an extremely important stage, which, in fact, determines your whole life. And a small child has creativity. He does things. He has a knife and he has an axe, and he makes something out of some firewood. That was my case. Yes, he gets cuts on his hands, yet he expresses himself somehow, he has this drive that accompanies him. And your whole environment, the kids in your neighborhood, what happens to them... When you look back, you see that you have lived out your whole life through playing.

The life of a small child is the same as that of an adult – if the same collisions are there. There is both courage and moments of weakness. There is analysis of why things are the way they are – what makes “him” stronger, what is “his” character like. You see how your surroundings are changing. In 1965, when I was seven years old, 20 years had passed since the end of the war. Newcomers had already moved into the workers’ housing on Cēsu iela, but there were still people there from the older generation. There was the street sweeper, the people in line at the shop, one of whom in front of you knows how to meow like a cat...visual memories of them.

At the corner of Cēsu iela, there were horses wearing feedbags of oats, waiting for the goods to be unloaded from their carts. Back then, butter and cottage cheese were wrapped in paper, cream was poured into a jar and topped with paper. They also had cod, which is no longer found in the Baltic Sea, but was a common fish at the time. And they put it all in your little net bag. We lived so ecologically, whereas now we throw away bags of plastic packaging every day. Back then, plastic was not even a thing. I remember the band “Čikāgas piecīši”[1] singing about sausages in cellophane, and then those sausages in cellophane appeared in our country, too. A ballpoint pen was a luxury item. My father bought me one from a sailor – a very nice one, with four colors. By way of that pen, I discovered that I was color blind. I was coloring what I thought to be a blue sea, but it turned out that I had colored it green. That’s how we found out that I couldn’t see colors. I wanted to be a sailor, but I couldn’t because of this.

All these things... You had to have a constant supply of firewood. I, for example, have been stoking various stoves for about 35 years of my life. I kept the stove going on Cēsu iela, then I did the same at the art school – there were shifts, and I had to come early so that it would be warm when the others arrived. Then I stoked the fire at Neiburga’s (Andra Neiburga, writer and artist – Ed.) flat on Zeļļu iela.

So that’s how firewood and wood became an organic part of your work.

Well, yes. A scene from childhood: the firewood was delivered, and then shortly thereafter, two legionnaires arrived on a motorcycle. They then somehow reconfigured the motorcycle so that there was a saw instead of a sidecar. For larger pieces of wood they used a “mega” saw, and they used it to saw firewood for everyone. All of this seems completely unimaginable to people today. And it is.

On Sundays, walking down Cēsu iela, where every window was open, you could hear someone singing in every apartment. There were no fancy recordings. They played records or people got together and sang in groups. People made music themselves. They sang, played the accordion or violin – you could still hear all of that. There were also other expressions of creativity, such as decorating windows in winter – people would put woolly insulation along their windows, and then arrange toys or dolls to “sit” on it. That was people’s creativity. It was a generally accepted thing. You can still see this in Tallinn.

Andris Breže’s object Aploks (Enclosure) / exhibition The State, 1994. Photo from the archive of the Latvian Centre for Contemporary Art

Still?

Yes, in the old town. A few years ago, I saw windows like that there. People expressed themselves naively and sincerely; it’s etched in my memory. Like frost flowers on a window. There will never be anything like that in double- or triple-glazed windows again, will there?

All these things create something, and you can’t escape those memories. That’s how my art is, too... Whatever it is, it’s not rational; there’s this poetic “background” to everything, this poetic feeling. The rational gets in the way. Most Western art is very rational, and poeticism is even disruptive. People sneer or laugh at it. Even a prudently conceived conceptual thing can, of course, be poetic – you just have to look at it differently. But in most cases, what I express is very... Well, I haven’t been able to get rid of this naive poeticism. It mostly follows me around like a dragging tail.

You mentioned poetics and poetry. How did you get into poetry?

Well, it happened one particular day in art history class, in my third year, when we were studying surrealism. The art history teacher “brought together” various creative expressions by illustrating them all with one line of Breton’s poetry. And somehow it all tied in with that day – a sunny day. Through the window I could see the light playing among the leaves of a tree. Somehow, that one line suddenly opened up a different understanding. The fact that what you do in art, you can also do in your head – without doing anything with your hands. You can resolve these situations, get the boost that is caused by good, creatively resolved work that surprises and uplifts you, the artist. And then you understand – damn it, I can do all of this quite easily; I don’t need anything, just a piece of paper to write it down so I don’t forget. Because what’s important is the combination of the line, the right arrangement of words. You just have to mark them down. Put it aside, and after a while you can simply look at it to return to that moment. Because that’s how it is. You begin to understand that you can arrive at this in a very simple way. I have abandoned many ideas in art because I can realize them in this way – in a different way, and get satisfaction without doing anything with my hands. When something pops into my head, I write it down and I end up going into another portal.

But you do not sign your poetry as Andris Breže.

Through my posters I had gained some recognition among a small circle of society, and I didn’t want others to know this discovery of mine – my other form of expression. I wanted it to have its own separate “line”. And then I simply noticed that when I rearrange the letters of my surname [Breže → Žebers – Ed.], this also sounds quite Latvian. I must admit that no one connected the two for a long time. It’s like a parallel line.

Andris Breže’s object Aploks (Enclosure) / exhibition The State, 1994. Photo from the archive of the Latvian Centre for Contemporary Art

A parallel life.

Yes, a parallel life because it’s different; and the two are contradictory. The contradiction is that in art, you can’t be illustrative. You have to do your own thing, but you can’t be too narrative. Of course, whatever it is and whatever the case, you are telling some kind of story, but there must be a secret in there. Whereas in poetry, you also have to reveal something. These kinds of phonetic and visual thinking differ from one another. For me, when I’m working on something... Well, for example, I recently had to submit a collection of poetry. I’ve pretty much done it – I just need to organize it – but I can’t right now because my head is focused on the exhibition right now, and I’ve pushed poetry to the side. It’s difficult to combine these two things. I have to finish one and then go back to the other. That’s how my world works.

But can poetry even exist in today’s reality? Do people still even write poetry?

A tremendous number of people write poetry. They do it, and the less they read, the more they write. I think we’ve reached a point in history that has never been seen before. Gadgets and screens have completely changed people. They take away their ability to concentrate. I don’t know where this will lead. Have you seen anyone on a park bench or on public transport with a book in their hands?

Actually, yes, quite recently on a train to Jūrmala. But I must admit, and I don’t know why, it seemed strange to me.

It used to be that parks were full of people with books in their hands.

Society has lost the ability to read and comprehend. The magazine Avots[2], which began publication in 1987, had circulation numbers unimaginable in today’s world. I suspect that it would be difficult to sell even 200 copies now.

The reason for Avots’ success was its content, because the authorities had kept a lot of things under wraps. And when they started printing all those things that had been banned, people read it because up to then, it had been inaccessible. That was the main thing. Later, it was no surprise that Avots naturally faded away, because people had satisfied their curiosity. Everything started to come out – censorship was lifted and everything became possible. The “forbidden fruit” effect disappeared, which, in my opinion, was very significant. And the desire to read also suddenly disappeared. The last issue of Avots, which was printed in Finland in 1995, was small and thin. Yet the Estonians still publish their “Avots”, which is called Vikerkaar (The Rainbow).

In Latvia, the overall cultural scene of the late 1980s and 90s was characterized by enormous energy, daring, and uncontrollable enthusiasm. I have a feeling that we have never experienced such a degree of frenzy (in a positive sense) since. It was...a “golden age”? How did it begin, why did it end, and how did it differ from our time?

Speaking about us back then... In my opinion, a strong generation emerged in the mid-1980s, and in all areas – art, poetry, music. In short, a strong group of creative young people had formed, a critical mass had been reached, and perhaps the motivation was the atmosphere of change. Although in the mid-1980s there was not yet any talk of any change, it seemed to me that I would never travel to, for example, Poland, or to any other foreign country in my lifetime. That I would never leave this environment in which I had grown up; that it was predetermined. Unless, for example, you joined the Communist Youth League, but that wasn’t our path. That was the feeling of the mid-80s – fatal. At the same time, our generation had already grown up very skeptical of everything around us and was looking for paths that diverged from those who still operated within the previous framework. The 80s and 90s were a time of great formation –when our generation came out to manifest itself.

But at the same time, it was not a rejection of the work of previous generations. It was simply that a generation that had begun to think differently had grown up, and there were enough of them. When they realized that so much of what they wanted to do was possible, it opened the floodgates and they began to pour out. The guild principle was at work – there was painting, graphic art... in short, there was fine art and there was applied art. It was completely impossible to jump into fine art from the applied arts. If you came from the applied arts and didn’t want to just make tables, chairs and pots, you had to get into fine art. While still in art school, Ojārs Pētersons and Ivars Mailītis had started participating in poster competitions and invited me to join them. These poster artists were a very egalitarian group who were interested in bringing in new blood. They treated us well. To a large extent, this was thanks to Kirke [Gunārs Kirke – Ed.], who led this group. He was very good at getting along with the authorities, but that didn’t affect us in any way. For example, he would organize competitions for designing posters promoting nature conservation or firefighting or something like that. We participated in them, and we were enraptured. We had good ideas, and we often won those competitions and received monetary prizes. For a young person still studying at art school, it is very important to gain some recognition – as well as some money. Through these posters, we entered the sub-category of graphic design, which included posters – in other words, we had entered the fine arts.

But the big break was Ojārs Ābols’s proposed and submitted exhibition Daba. Vide. Cilvēks (Nature. Environment. Man), which took place in 1984 in Riga’s St. Peter’s Church. Ābols had conceived it as something where other kinds of art could also be included. Different kinds of work. We understood immediately; it was to be a real break with tradition. Ojārs showed an object, and I, Valdis Ošs and Andra Neiburga submitted the object Brauciens zaļumos (Trip into the Greenery). Leonards Laganovskis, Hardijs Lediņš and Juris Putrāms also participated. Indulis Gailāns had a distinctly conceptual and innovative work. Moscow television came to film it, because it was the first time that something like this had been exhibited at an officially approved exhibition in the USSR. In Moscow, they had held the so-called “bulldozer exhibitions” and all sorts of other things.

Andris Breže’s object Aploks (Enclosure) / exhibition The State, 1994. Photo from the archive of the Latvian Centre for Contemporary Art

But that had been illicit, underground.

Yes, and here the underground was accepted. That’s where the dividing line was. Of course, the exhibition as a whole was one huge cacophony, because everyone participated – some of them just wanted to do something different, but without understanding how and why. For them, it wasn’t an organic breakthrough but rather a contrived one. Whereas we had been watching what was happening “there”. As in the Polish art and design magazine Projekt. There wasn’t much else. Maybe Kunstforum. But the breath of the [free] world was already coming in through them. At that time, thanks to the Solidarity movement, the Poles were strongly oriented towards the West.

Why did we do this? We were young, and each of us had absorbed our zeitgeist from some kind of mystical cloud. Once you had connected to it, you gained an understanding of your direction and had a plan of action. After a couple of years, we and our objects were accepted. It turned out that there was nothing terrible about them, just something different, and the world would not collapse because of it. In my opinion, a number of people suddenly felt that they belonged to this movement.

A sense of community. And those who belonged to it, and also the time itself, did not seem to be characterized by an attempt to fit into some conjuncture, narrative, or Western art scene. The driving force was to enjoy freedom; to do what seemed important – without thinking too much about the financial aspect. The support system for art is undoubtedly one of the cornerstones of cultural strategy, but the most important thing when writing funding proposals is not to lose sight of the art itself.

To a large extent, when the writing of proposals began when there was some possibility of receiving financial support. They understood how to write these proposals. Over time, they became very complicated and bureaucratic. But in the end, there arose the impression that if the artists didn’t get the money, they lost their inspiration and excitement – nobody did anything, nobody made anything. I’m not saying that all of this support isn’t necessary. It is, but it’s also a double-edged sword – it makes you start calculating. None of our projects came about because someone gave us money.

Returning to Nature. Environment. Man, where our Trip into the Greenery was exhibited... That car had been sitting in Valdis Ošiņš’s yard. Together with Valdis, we decided – let’s do this. In the same yard, we dug up the soil, mixed it with cement and smeared it over the car. We called a taxi and hooked up the car with a towrope. I got behind the wheel and steered to St. Peter’s Church. We pushed it inside and set it up for exhibition. That’s how we did things. We had to consider what you can procure yourself, what you can do with it, and who you can ask for a favor.

Those “men” [the sculpture “Masters of the Land” – Ed.] currently standing in the museum are not made of some kind of superior material, you know – they’re simply made of paper. Nothing is stopping you from picking up some newspapers, buying some PVA glue, and getting to work. Glue a formation together, take it apart. It was all about newspapers, because if you wanted to make something big, you had to take into account that you had to lift, move and deliver it yourself. If I had made it out of some other material... I need to know where I’m going to put it, what I’m going to do with it, I have to be able to lift it, put it down, move it, replace it.

There were, of course, some lucky breaks. Ojārs Pētersons, Juris Putrāms and I worked on Henrihs Vorkals’ crew at the “Māksla” conglomerate. This gave us access to a workshop in the former Kuznetsov factory, where the conditions were right for the creation of our first supergraphics. Without this, there would have been no supergraphics.

Andris Breže’s object Aploks (Enclosure) / exhibition The State, 1994. Photo from the archive of the Latvian Centre for Contemporary Art

Excitement and craziness dominated everything.

Yes, it seemed like you were doing something important. It was a necessary feeling – that what you were doing was important, new and interesting. Affirmation. That you were breaking new ground. But life went hand in hand with the economy and everything else. Interest in art waned in society. And artists also felt unappreciated. Apathy set in, the excitement disappeared. People involved in art began to be perceived as oddballs, fools.

The artist’s status disappeared.

Yes, which was also significant. Because if you didn’t have money, at least you had some kind of status in society. The fact that you had some kind of role in art was quite important. In a way, your recognition fed you, warmed you, and allowed your engine to keep running. When that disappeared, everyone became marginalized, and that was that... If marginalism in art has always been present in Western society, then here, in our oppressed society, artists had relatively greater freedom, some opportunity to express themselves, and flexible working hours. But later, when freelancing had the side effect of not being able to earn anything, artists slipped into the lowest economic strata of society.

In the West, financial coverage is provided through a well-organized cultural support system.

Yes – the art market, grants, mandatory percentages of construction budgets allocated to art purchases. They have a vision of what they want to see in their surroundings, what good exhibitions should be like. Every self-respecting small town comes up with some kind of biennial. And so our non-existent Latvian Museum of Contemporary Art has put us in an unequal position with Vilnius and Tallinn. The Estonians even have museums and centers in Tartu and Pärnu. The Lithuanians, meanwhile, have a number of internationally renowned artists. We, in my opinion, have none.

Why are art and artists necessary?

You might as well ask why people need poetry, for example. It doesn’t really matter...

But in reality, when you see an expression of creativity... A builder or a welder can also be creative; the most important thing is how their mind works, that they are not just a slave to their task. That they have a creative drive, which means there’s an opportunity for extraordinary solutions. Art is a driving force that gives people the opportunity to discover their creativity, find it, and apply it in completely different situations and things. Art affects you – it is an impulse that triggers creativity. And it is in every person. For some, it manifests itself more, for others – less. But when you come into contact with art, it is awakened and begins to work. And creativity is nothing more than the ability to look at things differently, more freely. That is the most important reason why art is necessary.

***

[1] “Čikāgas piecīši” (“The Chicago Five”) was a popular Latvian musical group in Chicago in the 1960s—2010s, its members having fled from Latvia during WWII. Their music was banned but very popular in Soviet Latvia, as bootleg tapes were widely available on the black market.

[2] The magazine Avots (The Source/Spring) was a literary magazine aimed at the youth audience.

Title image: Daina Ģeibaka