Unseen Layers: Edwin Schlossberg on Art, Perception, and Discovery

An interview with American artist Edwin Schlossberg

Edwin Schlossberg is an American artist and designer whose practice moves between language, science, and visual art. For more than five decades, he has explored how words, materials, and images shape the way we understand the world. Trained in both physics and literature, he has consistently worked across disciplines – from pioneering interactive environments to creating paintings that invite viewers to question what they see.

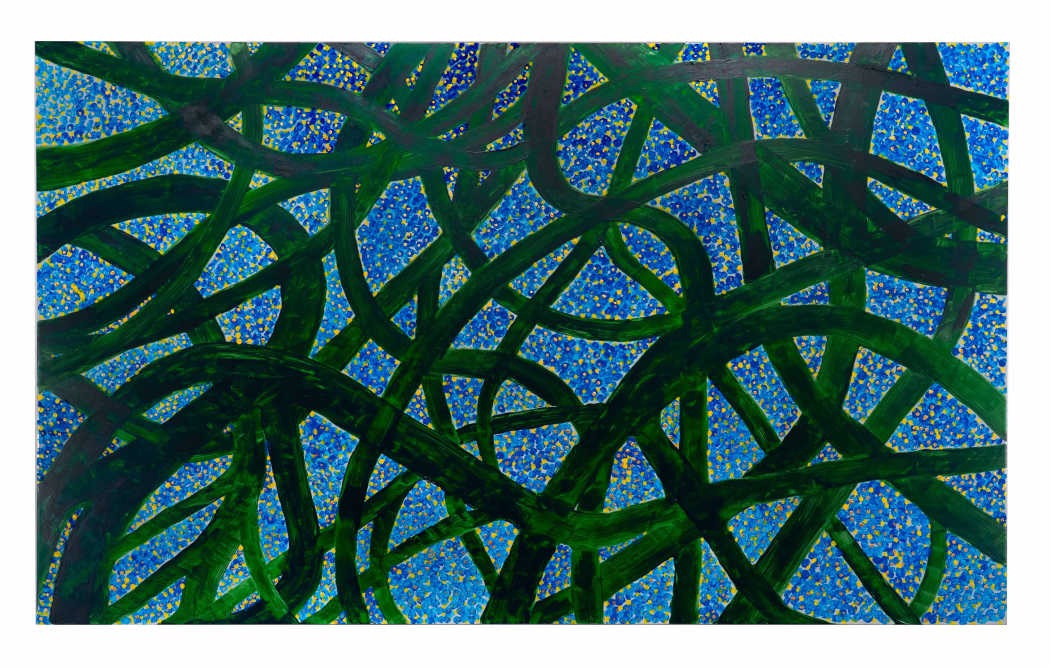

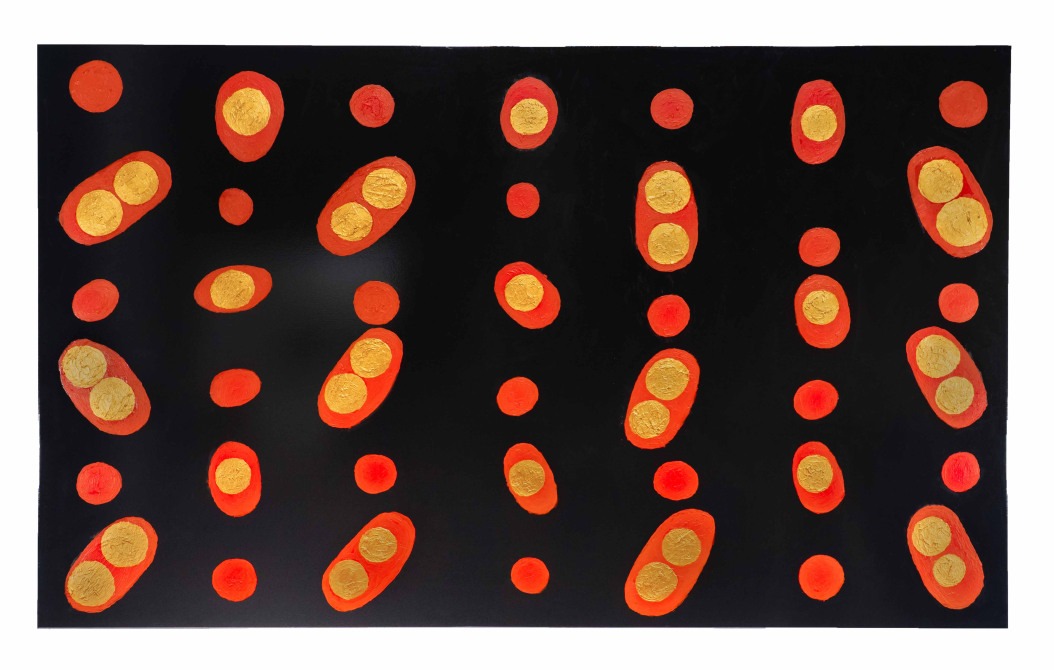

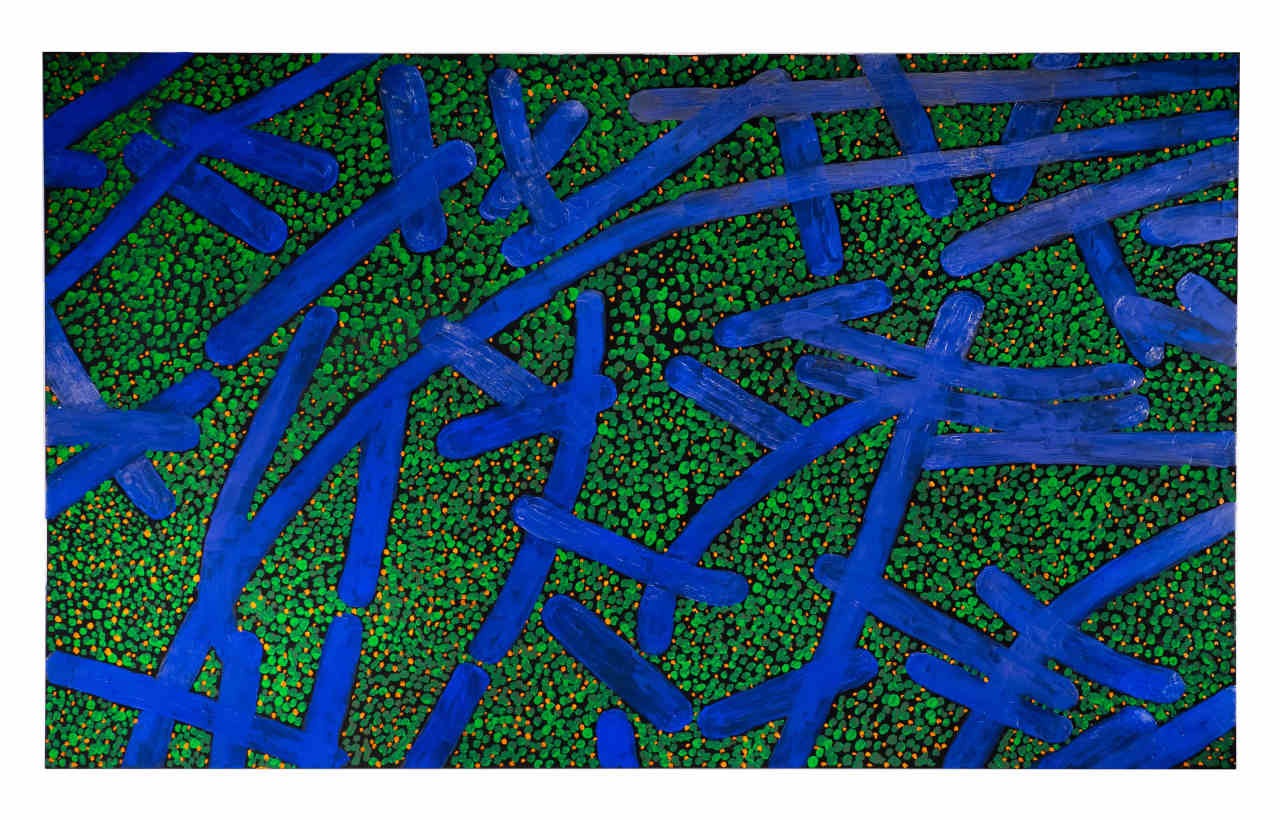

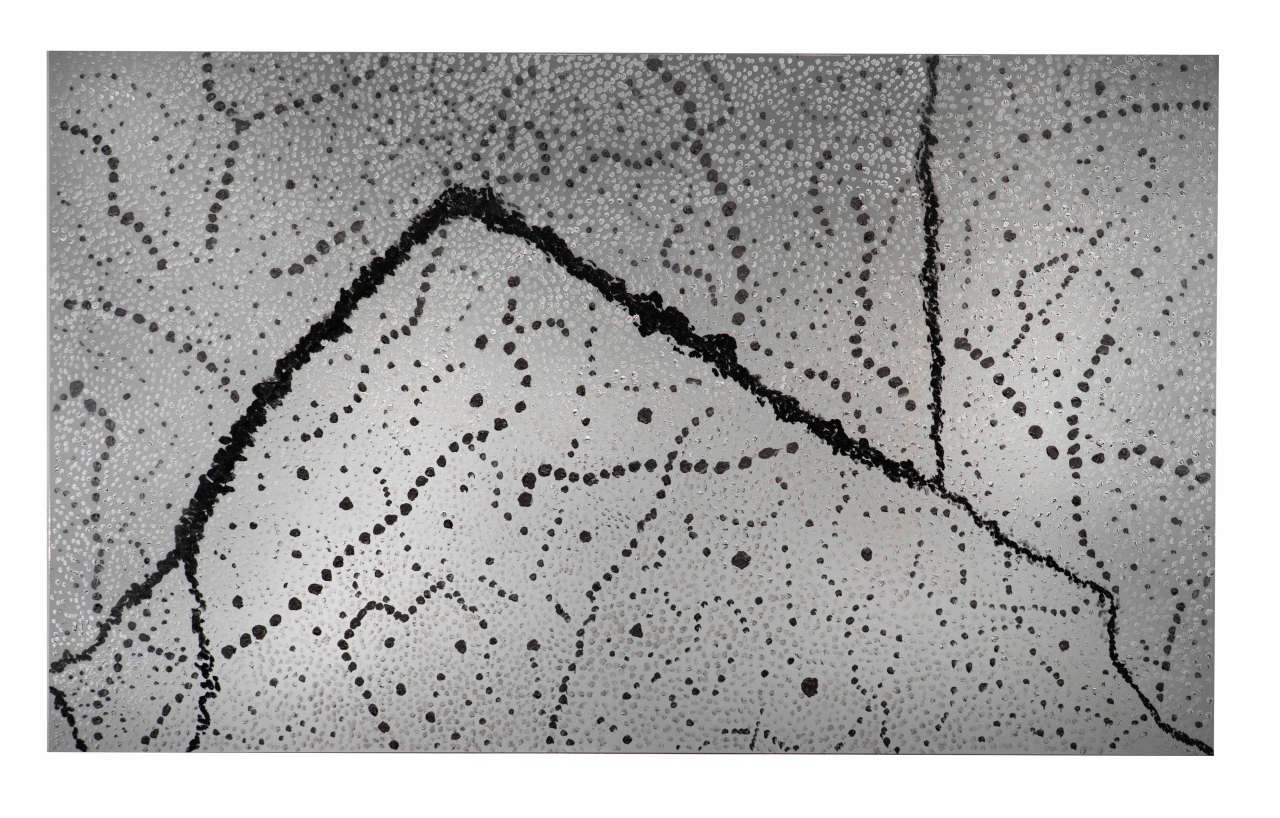

In his upcoming exhibition Unseen Layers at the Ronald Feldman Gallery in New York (March 5 to May 21, 2026), Schlossberg turns toward the microscopic and the cosmic at once. As writer and researcher Lara Pan writes in the exhibition catalogue, these works function as portals bridging “the realms of the microcosm and macrocosm,” revealing forces and patterns that pulse beneath the visible surface.

Using reflective materials and layered compositions, the paintings shift as the viewer moves, creating optical depth that mirrors the complexity of the universe itself.

Schlossberg’s intellectual rigor is paired with a distinctive sense of humor. He speaks of art as “irritation” – not in a negative sense, but as something that unsettles perception just enough to make us look again. Beneath the playfulness of language lies a sustained philosophical inquiry: how do we see, how do we understand, and how do we live within systems far larger than ourselves?

In this conversation, Schlossberg reflects on interdependency, discovery, interactivity, and the ongoing challenge of learning not just to see – but to truly look.

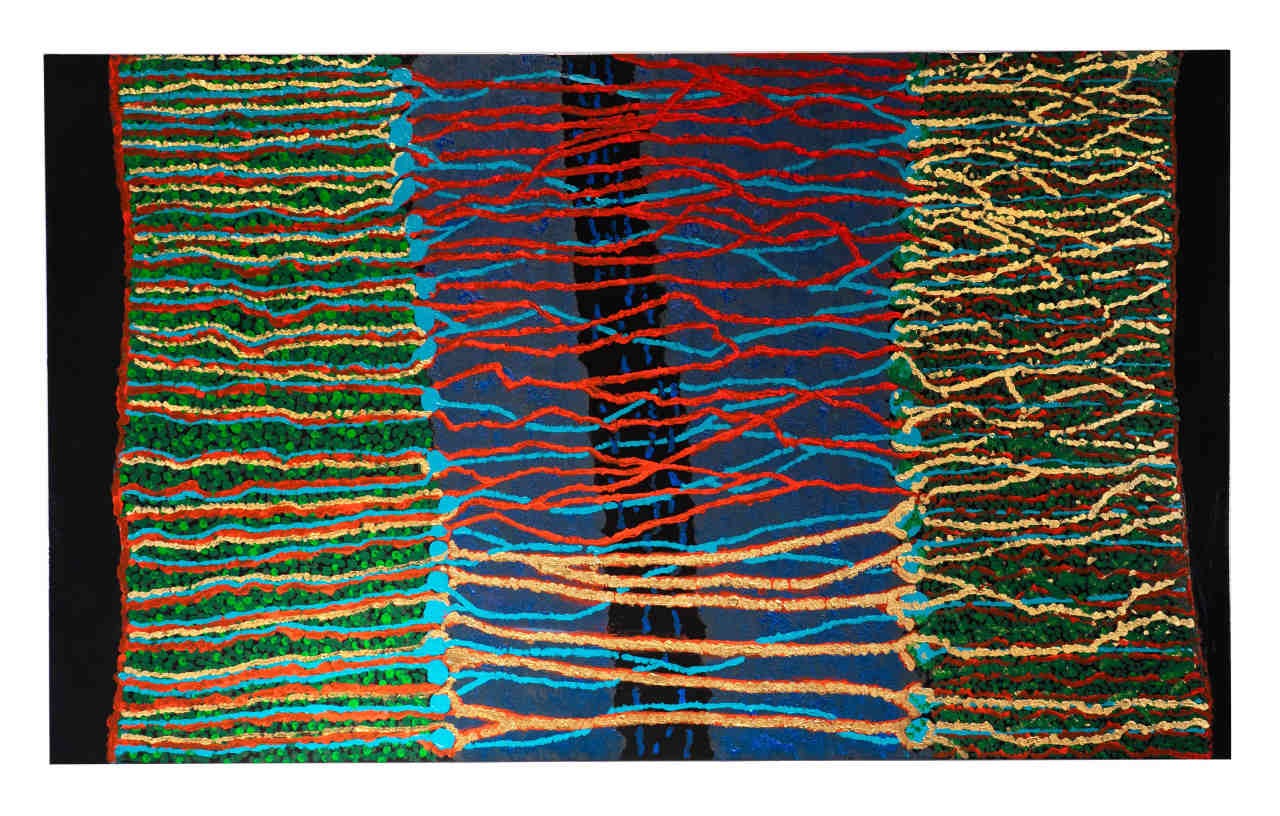

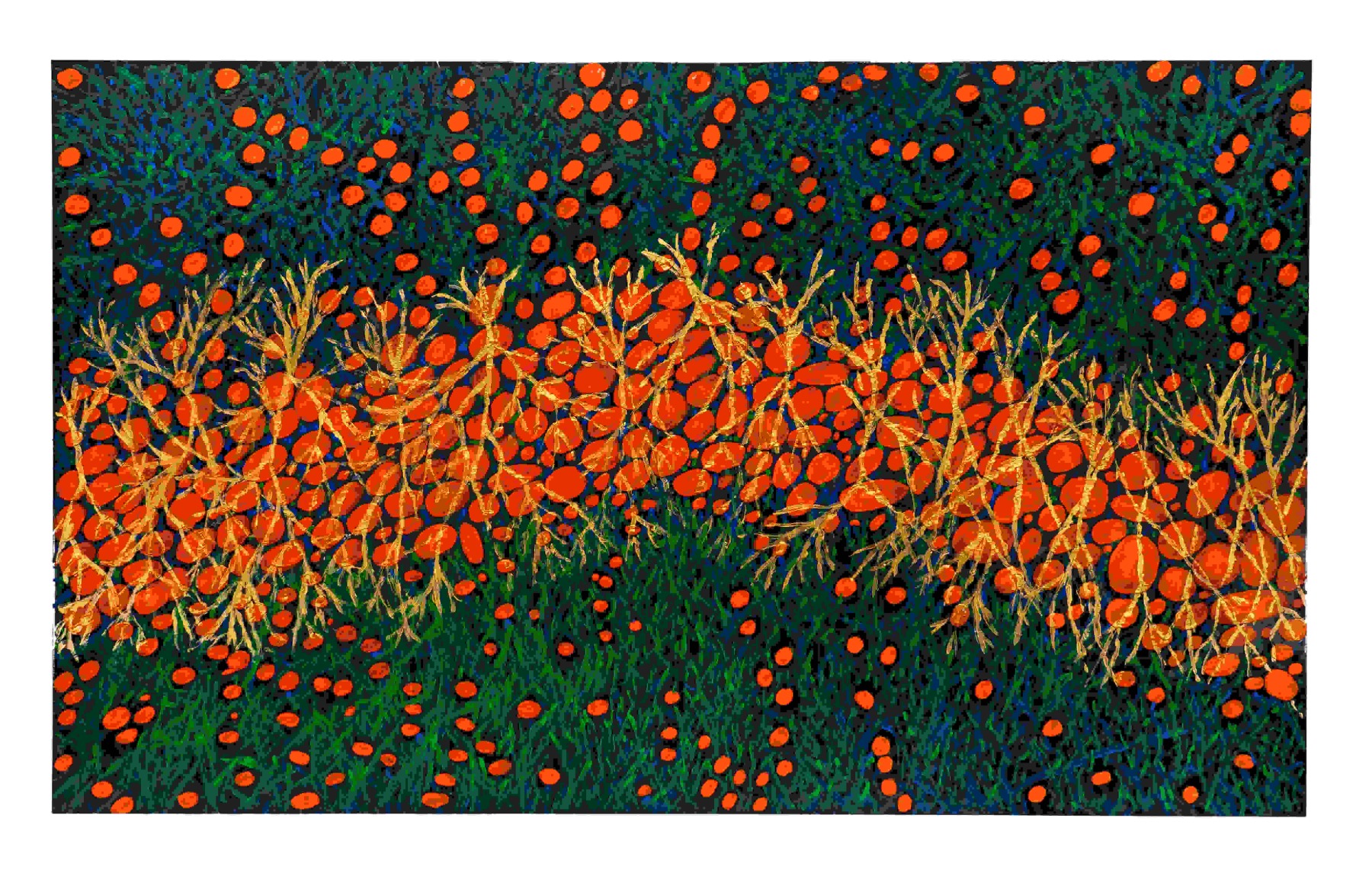

Edwin Schlossberg. Portrait of a New Filter, 2025. Aluminum with scotchlite and acrylic, 36x60 in. © Edwin Schlossberg. Courtesy the artist and Ronald Feldman Gallery, New York

As we sit here for this interview, I’ve been thinking about words. You’ve worked with them throughout your life – not just as content, but as a way of thinking. What do words mean to you?

Well, I think I’ve always loved thinking about words, because every word comes into being for a reason: people wanted to say something. They wanted to make a sound that could communicate an idea or a feeling – or, you know, a number, a size, all kinds of things. Without a language to talk about the world, it would be very difficult for people to have any real understanding of one another.

In that sense, the paintings I’ve just done are the first paintings I’ve made that don’t have words in them. All the earlier ones, in fact, were built around a word – not necessarily as a metaphor, but more as a kind of context.

But I felt that these paintings now live in a space where very few people understand the words usually used to describe it. So I wanted the colors and the positioning to invite you to think in words – to bring your own words to it – rather than having me write the words for you.

The reason I was thinking about this so much is that very few people have the vocabulary to understand science, and especially bioscience. People don’t really want to know how their bodies work, because it’s frightening.

So the idea of talking about scale – about what is actually happening – felt limiting if it stayed only in words. Instead, I tried to carry that into the transitions between colors, so that what you see is something real in the world, but so small that enlarging it becomes a way of translating it from a feeling into a reaction. I found that compelling.

Right now, biochemistry, biophysics – biology of every kind – has these new tools: dyes that can be introduced to identify tiny things that were never really visible before. But knowing whether something is a glial cell or whatever no longer felt essential to me. That wasn’t the point. What mattered was the feeling of interdependency.

I wanted to place the work on this material, Scotchlite, because it makes everything dynamic. As you move, the colors change, and in a sense the distance to what’s happening changes too. It feels almost like a living thing, because the act of seeing it unfolds within an environment – it isn’t just flat on the surface of the painting.

That’s what makes it exciting to walk past: it keeps changing color as you move in any direction. It’s probably the closest thing I could make to a kind of movie – not literally, but something dynamic. Even the angle of the lighting alters it, so the lights have to be positioned in a way that allows everything to stay in motion.

In that sense, it isn’t a reproduction of life, but a real moment – an invitation to see something in many different ways. The colors, the balance, the relationships between them are always shifting as you move around. It’s not life itself, but it’s a good experience of something like it.

And when it came to choosing the imagery, I looked through thousands of pictures and selected those that had the least resemblance to familiar objects. I wanted to avoid anything people could easily name – something that looks like a tomato, for instance. They might recognize it, even while knowing it isn’t one, and I wanted to move beyond that.

All of this made me think about the discovery process itself. When you can’t quite know what you’re looking at, you end up making metaphors in your mind anyway – we do that all the time. If you stand still, you get a kind of show, and as you move around, the show continues. That’s what I was trying to do.

I wanted to avoid a projected environment, like a movie or a film, and instead make something closer to how life actually works. It does ask something of you: not effort in order to find it beautiful, but effort to understand what you’re really looking at. I found all of that deeply engaging.

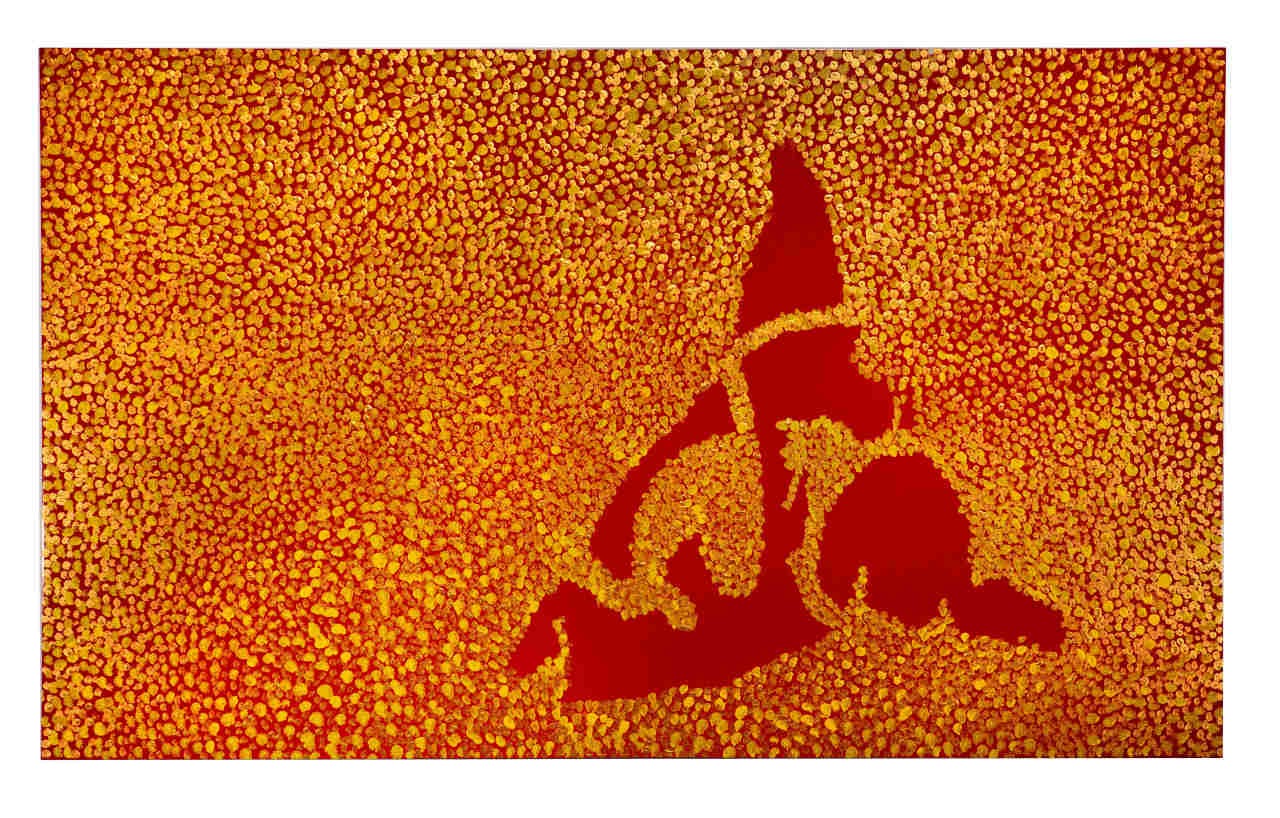

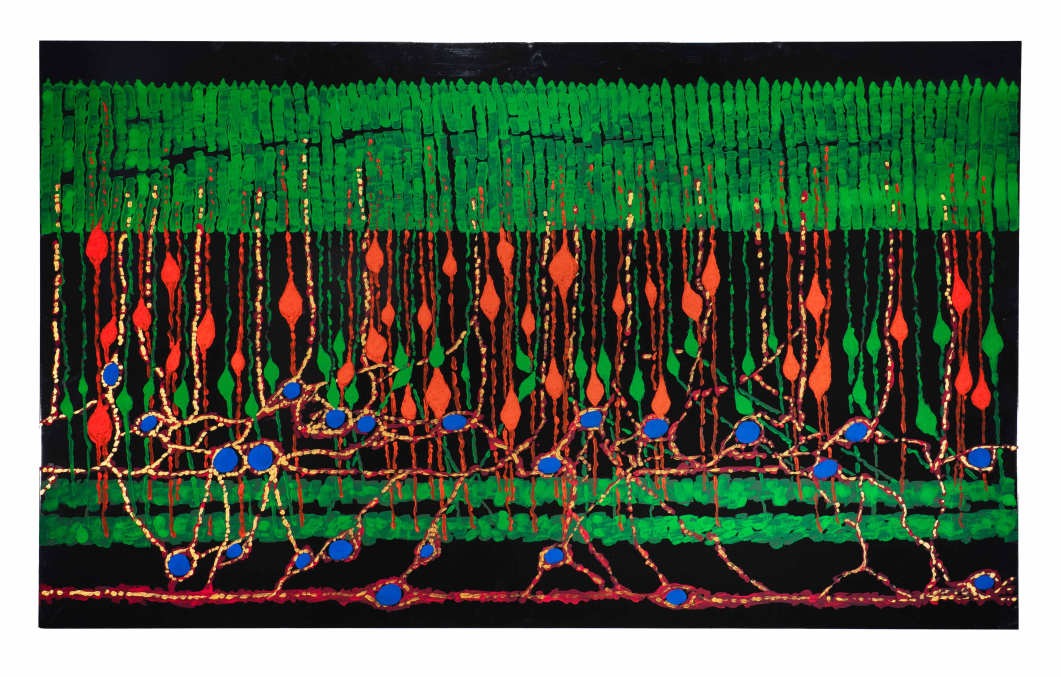

Edwin Schlossberg. Portrait of New Metal, 2023. Aluminum with scotchlite and acrylic, 36x60 in. © Edwin Schlossberg. Courtesy the artist and Ronald Feldman Gallery, New York

You mentioned the word life and the idea of what life is. Have you thought about that question yourself – what life is? After all, life isn’t only human life.

Well, the idea is, you know, that we really don’t have very good words for what life is. Interdependency is a good word. And I think a lot of people have been exposed to art and have been puzzled by it. The puzzle is usually, you know: why did someone do this? Is it sloppy? What is it?

So I thought it was really interesting to make something that is an unknown thing that has actually been seen – but then the question becomes, what does it mean that anything is being seen at all? In other words, it feels much more, in a sense, true to a more advanced understanding of what life is.

And I thought it was really an accomplishment to try to make that happen. It’s been great to work on it over the last three years, making these paintings.

But when you think about language, what matters most to you: the words themselves, or the silence and the space between them?

Yeah, I think it’s like the process itself. Process is like when you’re young and you don’t know what something is, but you know what you see. And then you start to say, well, that’s the orange thing, or that’s the, you know, and you accommodate by adding different words, so you can carry out the discovery.

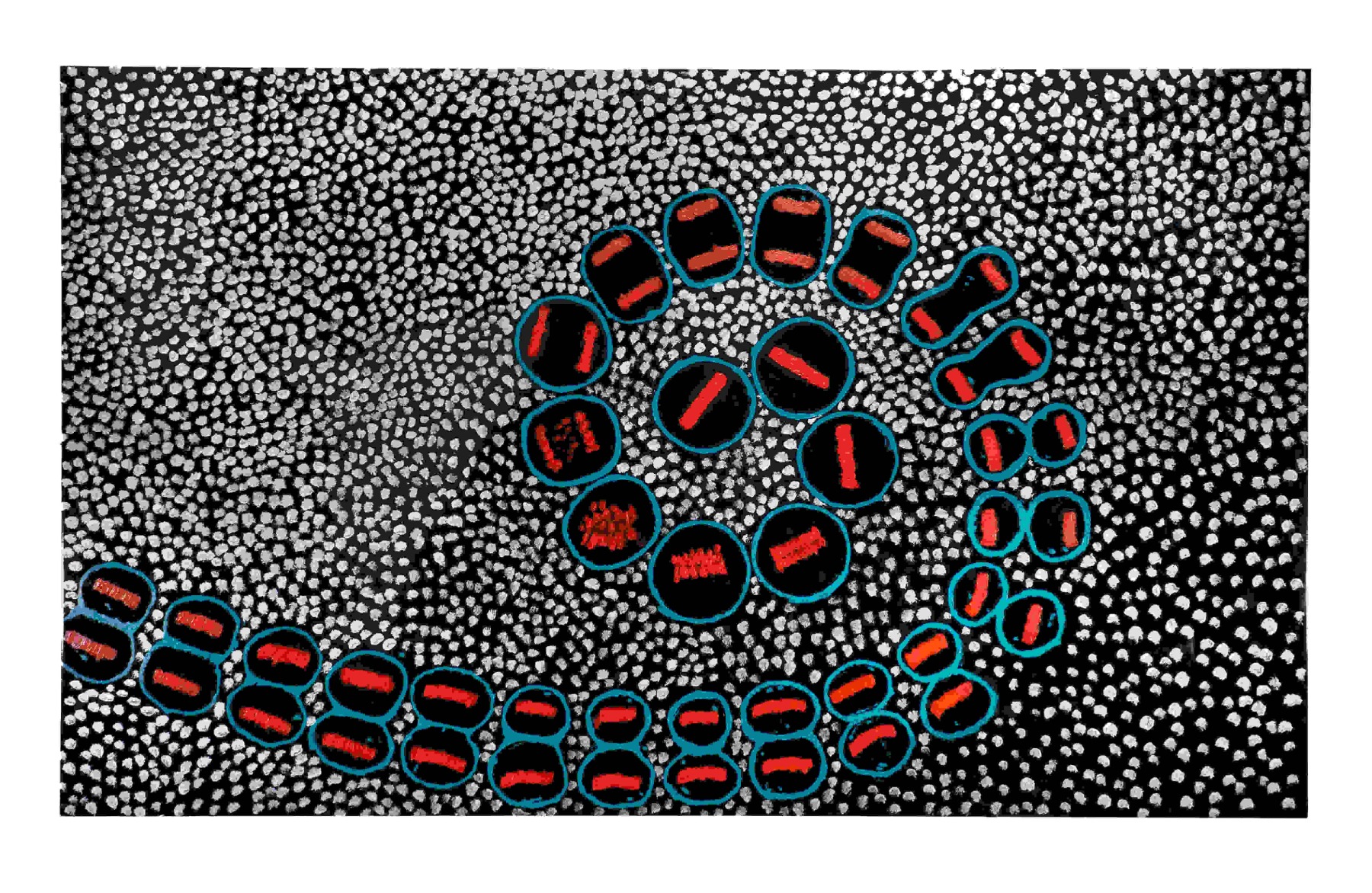

So this is the same thing – or a similar thing, but it’s also not. The part that’s really spectacular for me, in terms of intention and challenge, is imagining that this is going on inside you. That it’s you. Everybody is at this level; everybody is the same. I mean, not identical, but the structures are the same.

I think that’s one of the things that often happens: you look at a woman’s face, a man’s face – it could be anything. And then you brush that away and think, well, this is a good one, this is the interesting one. But in this situation, you have no idea whether there’s a good one or a bad one or anything like that. What matters is that this is the necessary thing for all the other things to exist.

So I like that. I like that way of not making it obscure, but making it a little bit challenging. But if we think about reality today, it feels really complex. In our everyday lives, we only grasp a small fraction of it, right? It’s very layered.

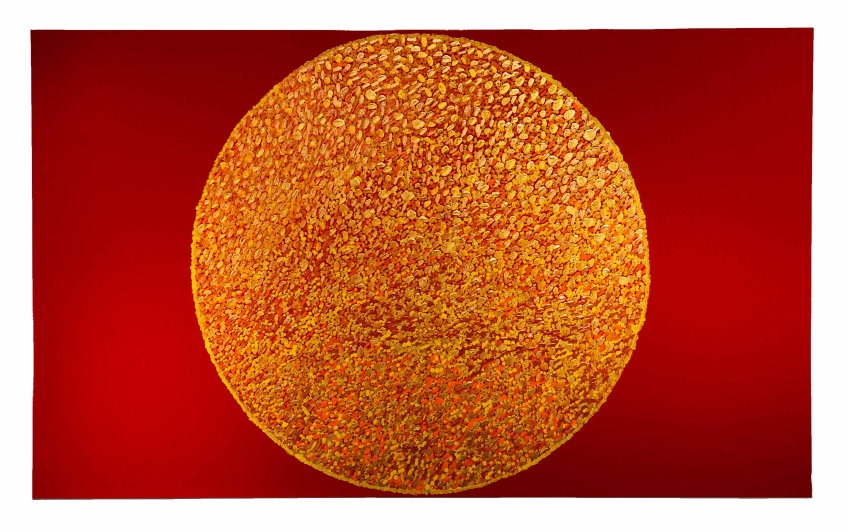

Edwin Schlossberg. Portrait of an Atom, 2023. Aluminum with scotchlite and acrylic, 36x60 in. © Edwin Schlossberg. Courtesy the artist and Ronald Feldman Gallery, New York

Do you think that through your paintings you somehow open – or can open – those layers for us, so we can discover the complexity of the reality we’re experiencing right now, in this moment? Because there is a reality behind me that is present, but I’m kind of not seeing it.

And also, you said that it’s difficult to speak in the language of science, because people usually don’t have enough words for it, and because we’re quite scared to look inside ourselves. Of course, intellectually, we know all this. We know that we’re made up of a huge number of atoms that are constantly moving. We know it – but we don’t really recognize it in our everyday lives. If we did start to recognize it, maybe it could change us as humans.

I mean, it’s sort of like a celebration of how complex the ability to live really is – and of the fact that you might want to know more about what that is, what that complexity actually means.

One of the paintings is based on a phenomenon in the world of photons. This comes from a scientific project where people decided to contain photons in one place to see how they behave with one another. What they discovered is that every time you put photons together like that, they form the same pattern. The little photons always make the same pattern.

So I made a painting of what that looks like, because to me it was extraordinary to think that photons – which we usually think of simply as light, or as the medium of light – have a behavior that’s set, that actually has a form. I think that’s just incredible.

Edwin Schlossberg. Portrait of Bacteria, 2023. Aluminum with scotchlite and acrylic, 36x60 in. © Edwin Schlossberg. Courtesy the artist and Ronald Feldman Gallery, New York

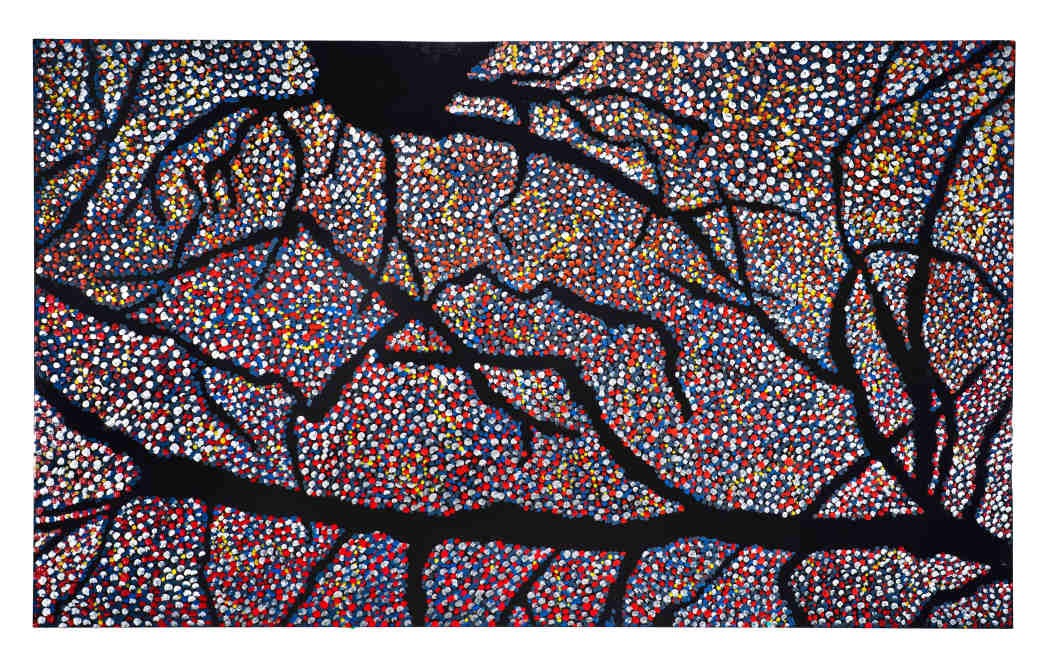

In some of the paintings in the exhibition, you can kind of glimpse references to sacred geometry and Aboriginal art. Do you think those codes are similar to the ones science is discovering today – ones our ancestors knew a long time ago?

Yes. I think that if you didn’t have words for things, you would use their forms to express something – like a circle, for instance. So I think it’s really interesting that Aboriginal work often looks like stars in the sky, or bubbles, you know, things like that.

The fact that they chose to paint in those forms feels both very sophisticated and, at the same time, very unsophisticated. And I think that’s why many of the paintings take on a kind of anthroposophic quality – in the sense that they resemble Aboriginal work – because being able to see the human body and its cells is like entering a new world.

When did you first discover Aboriginal art, and when did it start to interest you?

My wife, Caroline Kennedy, was the ambassador to Australia, so we lived there for three and a half years. And Aboriginal work really influenced me. You know, the jacket you’re wearing has a dot pattern, which references things like alligator skin and a variety of other elements.

So it’s always interesting to see that, and then to encounter it again on the smallest level of discovery. It gives everything a completely different meaning.

Edwin Schlossberg. Portrait of Brain Cells, 2024. Aluminum with scotchlite and acrylic, 36x60 in. © Edwin Schlossberg. Courtesy the artist and Ronald Feldman Gallery, New York

You’re talking about science through the language of art. Do you think science can be poetic?

Well, if it isn’t completely purposeful, in a sense, it can be. I mean, if there’s an aspiration toward communication beyond just structure, then it becomes, I think, artistic – and very important.

Because, you know, we’re all really grateful for how much we’ve discovered over the last even fifteen years about how life works at different scales. And it’s interesting that many of those discoveries were first made by looking at things like the stars – things that are very big, but that can also be understood as patterns, almost as if they were small.

Do you believe that we, as humans, will ever be able to understand human consciousness, or is it something that will remain a mystery forever?

I have no idea. I mean, I think about having read a lot of books about history and things like that, and I find it very difficult to imagine what people in the past were actually seeing – and what kinds of metaphors they were using to describe it all.

I think that’s what makes me really excited: the idea that I could make this kind of leap – to try to communicate, to try to bring together the visuals of the very small in a way that helps people understand what’s happening, and then to place it on a material that makes it dynamic. That makes me happy.

And I’m sure all of this will move into an entirely different dynamic, because when you look through micrographs and other tools, you’re going from something like a pencil all the way down to the atoms in a piece of lead. That’s really astonishing.

At the same time, I was trying to work in a way where no one was excluded. So that, in a sense, someone in an Aboriginal community could also find something to look at – and make metaphors from it, too.

Edwin Schlossberg. Portrait of DNA Unraveling, 2023. Aluminum with scotchlite and acrylic, 36x60 in. © Edwin Schlossberg. Courtesy the artist and Ronald Feldman Gallery, New York

So that means the viewer – the person who looks at your work – is very important to you?

Yes.

In a way, the viewer makes the artwork come alive. Is art alive if no one sees it?

You’ll never know.

I’d like to ask you about knowledge. Have you ever thought about what true knowledge is, and how it’s transmitted? And could it also be transmitted through art?

Yeah. I mean, I don’t know if you know this, but I earned my doctorate in both physics and English and American literature. So I was always moving back and forth between different tools of communication.

That’s something I really wanted to do, because I didn’t find it interesting enough to focus only on storytelling and metaphor. I also wanted to understand what the underlying structures of things were.

And when one looks at your work, sometimes you see a glimpse of pure abstraction. Sometimes there are references – like we mentioned earlier – to Aboriginal art or sacred geometry. But there’s never a moment when it feels fixed or categorized; it always stays open. Was that something you did intentionally – to blur that line?

Yeah.

Also, what I wanted to ask you about was the earlier period, when you were still using words in your art. Your first book was Words, Words, Words, and the introduction was written by Robert Rauschenberg.

I’m wondering – at that time, did you discuss these kinds of issues with him? Life, language, words, meanings?

Yeah, I mean, Robert Rauschenberg, Jasper Johns, Buckminster Fuller, John Cage, and Merce Cunningham were all sort of my pals when I was eighteen. And they were always asking me questions about physics or biology or whatever.

But it was really interesting to see how each of them related to language – you know, whether, when they looked at a scientific book, they were terrified, or whether they just never looked at it at all.

They were always interested in anything – in seeing things in any possible way. And in college, a lot of people were only interested in Latin or French or statistics.

I find artists much more interesting to talk with and to be around, because they don’t come with a fixed position about what the physical world means.

Edwin Schlossberg. Portrait of a Neuron, 2024. Aluminum with scotchlite and acrylic, 36x60 in. © Edwin Schlossberg. Courtesy the artist and Ronald Feldman Gallery, New York

I would also like to mention your early film Making Visible (1969), which feels strikingly relevant today. In many ways, it anticipated our current condition of technologically mediated perception. In the film, you spoke about invisible patterns – and in your current works, you reveal unseen layers connected to life in nature. As you said at the time, “In order to make this image visible to you, it had to become invisible.”

Your present exhibition continues this exploration of invisible structures, language, and hidden causes. There is a clear continuity between your early practice and the work you are creating now. That connection is informed by science, yet it feels increasingly organic – even spiritual. In a sense, it is about building bridges.

I think the interesting thing about that statement – about building bridges – is that, for me, that’s really what I’m looking for. If I’m searching for something, that’s what it is. I’m trying not to irritate people in the sense of making them feel they don’t know what they’re seeing, but rather to move them toward something more interesting.

I mean, everything I’ve been working on is about trying not to rely on the usual way of seeing things, but to disturb it slightly. “Irritate” isn’t the right word – it’s more that it unsettles you, or confuses you just a little. But it’s still real enough that you know you’re looking at something real. And that’s what’s interesting to me.

Edwin Schlossberg. Portrait of Neurons Bridge, 2025. Aluminum with scotchlite and acrylic, 36x60 in. © Edwin Schlossberg. Courtesy the artist and Ronald Feldman Gallery, New York

You’re looking at something real – but it’s not just what you think you’re looking at, because you’re constantly uncovering more and more layers?

Right – that’s exactly why I call them unseen layers.

What do you remember most from your work with Buckminster Fuller? How did it shape your thinking – and perhaps even the film you made? As I understand it, Andy Warhol also appears in it in some way.

Well, Buckminster Fuller was interested in everything, but in a way he was much more of an engineer. I mean, he wasn’t formally an engineer, but he was always thinking about how to make things – how to construct them. I think his aspiration was really about developing materials and ways of building that could create new kinds of structures.

At the same time, he was very interested in anything that differed from the usual ways people saw the world. He loved geometry, and he also cared deeply about materiality – about how materials could create different kinds of places for people to inhabit. And he was also, in a sense, a poetic historian, because he used poetry almost as a tool of discovery.

Jasper Johns and John Cage, on the other hand, were more interested in the experience of seeing something they hadn’t seen before – that moment of “whoa.” They weren’t focused on specific content so much as on the experience of themselves in relation to objects.

So I was very fortunate to bump into all of those people and to become friends with them.

Edwin Schlossberg. Portrait of Photons Gathering, 2023. Aluminum with scotchlite and acrylic, 36x60 in. © Edwin Schlossberg. Courtesy the artist and Ronald Feldman Gallery, New York

Did you also work with Buckminster Fuller when he was working on a dome?

Well, by the time he was working on the dome, it was already a product. So there wasn’t anything fundamentally new about it – it was more a question of what materials to use.

The problem with domes, which still exists today, is that there isn’t really a material you can use that won’t expand when the sun shines on it. And when the material expands, it can create leaks in the structure. So it wasn’t originally the most efficient solution. It became more efficient with the invention of adhesives that can stretch and adjust under different conditions.

It’s like different people have their own kind of radar – they pick up on certain problems they want to solve. And that was interesting to watch.

But it was fantastic to meet all those people and become friends with them.

Edwin Schlossberg. Portrait of Mouse Brain, 2023. Aluminum with scotchlite and acrylic, 36x60 in. © Edwin Schlossberg. Courtesy the artist and Ronald Feldman Gallery, New York

Materiality has always seemed very important in your painting – the surface, the texture, the way the material itself alters perception. Is that your way of expanding the boundaries of painting, of making it feel limitless?

I don’t think I’ve really thought about it that way. I just knew that if I could figure out something to do with the material, then I could work with it. But I don’t know whether that’s interesting for a lot of people. It becomes a different kind of communication, and also a different kind of purpose.

You know, people have very different ideas about what we call art – painting or sculpture. And I’m not sure people really think about it in those terms. Some of the really great work is still done simply with materials and with a kind of metaphor, or a characteristic the artist wants to express. They’re not necessarily looking for something beyond that.

Edwin Schlossberg. Portrait of Cell Division, 2023. Aluminum with scotchlite and acrylic, 36x60 in. © Edwin Schlossberg. Courtesy the artist and Ronald Feldman Gallery, New York

If I asked you what painting is, what would your answer be?

Well, it’s about creating something you can see that takes you into something you couldn’t see before. It’s about making something attractive enough that it makes you puzzle over what it is – giving it enough geometry and color and familiar elements to draw you in, and then turning it into a kind of puzzle about what you’re actually looking at.

I think that especially nowadays, for many people, it’s important to relearn how to look. When we go to museums, we often feel we don’t have enough time to really stand in front of an artwork – so everything just passes by. What would you advise? How can we train ourselves to look more carefully – and what should we really be looking for when we stand in front of a painting?

Yeah, I think that question really comes down to what’s important to you. If something feels important, you go to a museum with the intention of spending time. If you don’t have that intention, you might as well not go. I don’t mean that in the sense of wanting to be a scholar or anything like that – but you have to want to see something.

Gertrude Stein once suggested something like “all art is irritation,” and I’ve always liked that idea. Art should make you see differently. It should make you work a little — make you ask: Is this a story? Is this a context that’s asking me to understand relationships? What is it?

I think if it’s art, it unsettles you in some way.

There’s one more aspect of your work I’d like to ask about – the idea of interactivity. It’s such a common term today, but in the 1970s it meant something very different. How do you remember the first time you began to use it? And how was it received?

I don’t know. I think it really began when I was working on the first job I ever had – designing the Brooklyn Children’s Museum. That was probably the first time I consciously wanted to create experiences that were engaging – experiences where people discovered things together, formed connections, and did things they couldn’t do alone. And all of that became revealed through the work.

So I guess that’s when I first articulated that interactivity was very important to me. Buckminster Fuller also talked about interactivity, but what he really meant was the interdependency of materials, rather than people.

Edwin Schlossberg. Portrait of Glial Cell, 2023. Aluminum with scotchlite and acrylic, 36x60 in. © Edwin Schlossberg. Courtesy the artist and Ronald Feldman Gallery, New York

Is it still important to you – perhaps on a different level?

Yes, always. When I was eight years old, I went to a summer camp where we were taken into the woods. We had to build our own space, put up our tents, and cook together. I went back to that camp for several summers, and I think that experience shaped me early on.

I had to work with ten other boys and a counselor just to live in the forest. And I think that’s when I began to understand how important that kind of shared experience is.

When I look at your work, I also think about the word discovery. We use it when something new is found in science or in other fields. But for me, it always has a connection to the past – because when we discover something, it has already existed. It’s already there.

There are so many things still to discover, and each time we discover something new, we realize how much we didn’t know before. What does discovery mean to you – especially in your art practice? How do you think about it?

Well, going back to what I said about “all art is irritation” – the idea is that irritation, which sounds like a negative word, is actually a positive one. It means you’ve created something that doesn’t simply soothe you or make you think, “Oh, that’s a nice picture of a lake,” or “That’s a pretty woman,” or something like that.

Instead, there’s something that isn’t quite right, or not quite organized – something that unsettles the eye a little. And that irritation makes you look again. In a way, that’s why photography as an art form is very difficult. I mean, it is an art, of course, but it’s challenging because, with modern tools, it’s very easy to produce an image.

Edwin Schlossberg. Portrait of a Retina, 2023. Aluminum with scotchlite and acrylic, 36x60 in. © Edwin Schlossberg. Courtesy the artist and Ronald Feldman Gallery, New York

From one side, yes. But from another side, there is the photographer’s special gaze – the ability to catch a particular moment. And that happens in other forms of art as well. It’s about a way of seeing. There are many things you could capture, but you choose exactly this one – and then that image resonates.

Yeah, but again, it’s like picking someone’s face out of a crowd, you know. Or looking at sixteen flowers and choosing one of them. It’s about sensing that something stands out – that this is different from that, or somehow more compelling. And then you begin to understand that there’s always a kind of irritation involved.

I was really astounded when I saw this image of photons gathering in exactly the same place, organizing themselves in exactly the same way every time they were enclosed. I found that irritating – in a good way – because I kept thinking, why would they do that?

And then you start asking: what forces are making them behave that way? There must be something shaping that pattern, something drawing them into it. And that’s when it becomes very, very interesting.

Yes, because it’s always a question of perception. If one day we were able to see everything – the movement of photons, fractals, all of it – but we couldn’t organize it in the way we do now, through our own eyes and our experience, it might feel like a completely different world. And yet, perhaps that world already exists somewhere, in parallel.

Yeah, but I think when you begin to see that, you realize that the universe is this vast thing, with everything going on inside it. And the idea of being able to understand even a small part of it – or to see a pattern that gives you some solace – is very powerful.

It could be something like watching a group of people playing beautifully together, or even looking at something that feels unsettling. I mean, I don’t necessarily want to focus on what’s awful, so I wouldn’t include that – but those are the kinds of experiences that make me want to think about how I could present them, so that someone else could discover them too.

Have you ever thought about what your mission in life might be – why you came into this universe in human form?

No, I haven’t. I remember a quote – I can’t recall who said it – something like, “Don’t think about something too big, or your head will fall off.” I’ve always liked that idea.I can only go as big as I’m able to go. And then the challenge is to go a little bigger. Always.

Edwin Schlossberg. Portrait of the Sun Shining, 2023. Aluminum with scotchlite and acrylic, 36x60 in. © Edwin Schlossberg. Courtesy the artist and Ronald Feldman Gallery, New York

What will your next exhibition be after this one?

I don’t know. You know, there are so many fantastic sources of communication in science now that produce extraordinary material – mostly in photography, but also in writing. I read the best science and technology magazines all the time. Nature, for example, is an unbelievable source of discovery and inspiration.

The scientific world also has a real sense of dignity and aspiration. There are many people who work in it, in different ways, who are truly admirable – because they want to discover things, to make things better. They’re deeply opposed to cheating or causing harm or simply trying to make money for its own sake.

It’s a very aspirational institution. And it’s astonishing how valuable science is – and how important a publication like Nature is. When you see political leaders attacking it, you realize just how significant it must be. And that’s difficult to witness.

I also think art is very important – especially in times like these. And art has always been important, since the very beginning of humanity.

Yeah, I agree. After all, my middle name is Art – Edwin Arthur Schlossberg.

Thank you very much.

Title image – Courtesy of Edwin Schlossberg