An Artist Can Stir Up the World

12/05/2011

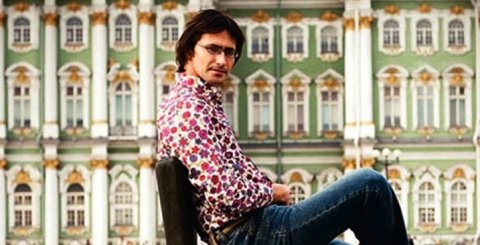

This interview with Dmitry Ozerkov, director of the contemporary art department at the State Hermitage Museum, took place in Riga a couple hours before the winner of the second annual Purvītis Prize was chosen. It was one of the coldest days in February. Ozerkov is a short, boyish-looking man between the ages of thirty and forty. On the way from the Arsenals Exhibition Hall to the restaurant chosen for lunch, it was hard not to feel sorry for him—he was dressed in a thin jacket, with neither gloves nor hat. It turns out he had just flow in from Madrid. His assistant had planned his travel itineraries, and he hadn’t paid much attention to where he was flying. Nevertheless, Ozerkov was cheerful and polite, and expressed traditional Russian compliments to Riga for the good job of its janitors. He said that in St. Petersburg he moved around only by car, in order to avoid the snowdrifts, puddles, and wandering dogs. “Russians pity every little dog, that’s why they are so fierce,” he explained.

Vilnis Vējš: Our conversation is taking place before the Purvītis Prize awards ceremony. The award is granted for the greatest achievements in Latvian art. Does this local competition seem interesting to you? And in general, do national differences still exist in art?

Dmitry Ozerkov: I think that when separate nations existed, when Europe still hadn’t united—when Germany was still divided between West and East—European nations found it important to emphasize their national uniqueness. For example, we can differentiate 1990s German art from the French art of the same period. But what’s happened is that now, when nations have united, art has somehow leveled out too. Professionalism has appeared. Looking at a work of art, first of all we see the professional level at which it was created. Before an artist arrives in the current art scene, he must reach this level. This applies to photography, video, and painting. If the required professionalism isn’t there, this can be seen right away. Of course, you can purposely work unprofessionally, so that it looks unprofessional, though this is done specially. In this situation where a unified level exists, a unified scene that moves from Venice to Basel to Kassel to Miami, a party takes place—at this level there are also projects that work directly with national differences. I looked at your eight artists, and to me they seem of equal value in a very interesting way.

You can sense the context, in which the traits characteristic of precisely this region appear. For example, I was surprised to see that an artist born in 1943 is very similar to an artist born in 1977. It’s true, they live in the same nation, the same environment, they speak the same language, if looked at in a global context. What is the common element in this? I think it’s a love for texture, for facture. A tactile perception of paper, fabric, and wood. Ecology, of course, a focus on nature. Furthermore, I undoubtedly saw a sort of political correctness, even a social correctness. There weren’t any harsh perversions—naked bodies, violence—against people or animals, the kinds of things that exist in society. It’s clear that the general problems which exist in the world are represented in any society. But these artists concentrated on the things that I mentioned before; therefore, for them art is more related to these things. That’s an indicator. To me, this seems like the virtue of Latvian art, which says, Look—our art, our school, is this like.

It’s interesting that you mention school. Do you think that school has a significance?

I think that it does. A school exists. I think that’s the next step after a general professional level. What is interesting right now—the school issue is complicated… We look, for instance, at a British artist who was born in Africa. And we see that for him the African theme supposedly dominates. But we conclude that we relate to him not just as an artist with British or African origins, but we are interested in precisely this mixture: a Brit with an African background. Your exhibit, too, has young people that have traveled somewhere, studied somewhere else, but within them is some inner “schoolchild-like”—from the word “school”—attachment to specific themes.

I recently wrote in my blog that “professionalism” and “school” have become problematic in art influenced by the avant-garde approach—to work contrary to what is taught in schools, contrary to tradition. And this in itself has turned into almost the dominant tradition in the last hundred years.

I understand the avant-garde more as a form of thinking than as a direction. We say the “Russian avant-garde” or the “Italian avant-garde,” but we are actually thinking about a form that is contrary to any tradition. I don’t know… I think that the avant-garde is always present, but it comes about precisely at the moment when a school exists, a specific position.

And I think that an avant-garde doubts a school precisely to the same extent that a school determines an avant-garde. This change takes place when a new generation comes about that negates all that has come before, rises up against the authorities and says, “They are all idiots, we will do the opposite.” That’s a normal process. In any event, I judge Latvian art based on what I know—and that is very little—and see only that which has been exhibited. This sooner shows a school rather than its negation. Because these people speak in one language and obviously understand one another.

You’ve arrived in Riga directly from ARCO in Madrid. You constantly follow new tendencies in the art world. What do they look like right now? A year ago people were speaking about the actualization of modernist forms. Perhaps because American galleries had the status of special guests, there were many abstract works.

It’s interesting that in Russia there aren’t any abstractions at all. All the painters are realists, the photographers are realists or surrealists, and the installation artists are realists too. It’s possible that for the next generations, early modernist art will be a new discovery. At ARCO there were maybe three interesting abstract works. I’d sooner say that the dominant element is a game with materials and forms, with contexts, a game with words and meanings, a sometimes hooligan-like form of expression about that which can’t be said. Many words are based on some original technique. Abstraction has imperceptibly disappeared.

Right now in St. Petersburg there are several artists who work realistically and utilize abstraction to their own benefit. For instance, Ivan Plyushch. With smeared fields and erased contours. There’s a reflection—postmodernism has gone, but what to do next? There is no unified style; there are individual projects that insinuate themselves into this empty space like wedges. They attract attention to themselves precisely because of the surrounding stylistic uncertainty. For example, a video that takes effect somehow directly, or a color arrangmenet that somehow specially detonates the perception. In these project you can recognize individual artists, but it’s not clear what to call them—not painters, not sculptors, and not installation artists. They do all three, with their own, strange techniques. In these projects the artist, gallery owner, and buyer all meet.

Does art have at its disposal the resources to shout over advertisements, the mass media, and the entertainment industry? And does it even need to do this?

To shout louder in order to attract attention—that is the essence of advertising. An artist’s goal is to express something that unsettles him. An artist does not have to do the same thing as an advertisement. An artist’s shout is intended for those who understand him. Of course, institutions—galleries and museums—can present an artist in such a way that he makes a louder noise. But that’s not an artist’s business. Nevertheless, he must be up to a certain level, in order for someone to advertise him.

Exhibits are often advertised with loud slogans and scandalous news, and organizers try to interest audiences with shocking details taken out of context. Art is associated with fame and money. Is this deception? Because when you go to an exhibit, you see that art isn’t abut that. Art is about something else entirely.

I think that art has enormous potential. And artists, of course, are capable of utilizing this potential. That is a very powerful weapon. A regular citizen has some sort of job, salary, relaxation, and perhaps some other pastime between work and relaxation. That’s it. An artist can destroy this bourgeois world, not in the sense that he can deceive, such sell a painting for a higher price or something like that—no. An artist can stir up the world so much that he makes you think: Where I am really going? Why do I work—in order to relax, or do I relax in order to spend money? An artist has this key to turn a person’s brain. A curator or someone else can’t do this. Television—yes, but that’s entertainment. An artist is capable of something more.