About Potatoes?

13/09/2012

On his recent visit to Latvia, the Croatian-born, Parisian-based artist Braco Dimitrijević (1948) tried out the Aerodium wind tunnel and took an aerial tour of Cēsis in a four-seater airplane. Adrenaline-pumping activities have been the norm for Dimitrijević since his youth, when he strayed from the artistic path to that of a professional downhill skier – because in sports, it’s easier to tell who the winner is. However, he never really managed to distance himself from art, and is now deemed to be one of the first principals of conceptual art. One may doubt this, but then you must take into consideration that he created his first piece of conceptual art at age ten, when he made a World Flag from a rag used to clean paintbrushes. It was a little boy’s attempt at solving the problem of ships having to constantly change the flag they flew, which was dependent on the national waters in which the ship happened to be in at the moment. Braco’s father was a painter, which explains why the boy’s first solo show was organized at such a young age. “I was an expressionist at the time. When my parents went out, I would sneak into my father’s studio and paint. But I had to be quick about it, and finish before they came home.”

Braco Dimitrijević. Photo: Katrīna Ģelze

Braco Dimitrijević’s installation “Sailing to Post-History” is on view in The Latvian National Museum of Art, Main Building, through October 21st. This summer it was exhibited also in the Castle Barn during the Cēsis Art Festival, which is one of the most established contemporary art festivals in Latvia; the piece was shown in Venice’s International Gallery of Modern Art – Palazzo Ca’Pesaro, in 2009, as part of the 53rd Venice Art Biennial. “Post-history” is a term coined by the artist himself, denoting the time of simultaneous co-existence of different values, defined by a diversity of the points of departure on which the evaluation is based. Dimitrijević’s works have been exhibited in the world’s most notable museums and art galleries, and he has had solo shows at London’s Tate gallery, Bern’s Kunsthalle, the Ludwig Museum in Cologne, Kunsthalle Düsseldorf, Vienna’s MUMOK, St. Petersburg’s Russian Museum, Ullens Contemporary Art Center in Beijing, and the Paris Musée d’Orsay. Dimitrijević has contributed to Kassel’s documenta (series 5, 6, and 9) P, and has participated in the biennials of Venice and other world cities. I met with Braco Dimitrijević in Cēsis, shortly before the opening of the Cēsis Art Festival. He suggests we take a couple of the folding chairs that are stacked in a corner, and we sit down among the “Post-History Ships”.

“Sailing to Post-History”, in the Cēsis Castle Barn

You developed the idea of “post-history” almost 40 years ago. But in the West, most of society still trusts in history, while you are convinced that it is “a mistake” to place individual events in the forefront – because the world has always has been much more complicated than that. Do you have an idea as to why preconceptions don’t change much?

History is very important to everyone. The idea of “post-history” is to take a subjective approach, that is, an understanding that several truths exist. But in Western civilization, there has always been one dominant idea – one model – upon which history is formed.

But why does this understanding continue to resist change?

Civilization itself has not changed much. Even in comparison to that of hundreds of years ago. Once, I drove from Brussels to Geneva through the sites of ancient war-fields, where battles had raged in the 18th century and both of the World Wars. In observing the landscape, including bunkers and other types of hideouts and “traps”, I concluded that over the course of history, technologies may have changed, but the way of thinking had not. Already in prehistoric times people would dig a pit, cover it with branches and leaves, and wait until somebody fell in; in the 20th century, these were concrete bunkers, where those inside sat and waited until the enemy approached while they remained unnoticed. This is, of course, a drastic example, but there are more.

You defend the idea that time is not linear. Does this also apply to every individual’s personal experience of time, and not just to world history?

Yes, I accept that there are dimensions in which time can change its course – where it is possible to stop it, or speed it up. I’ve experienced this myself, when I used to participate in professional sports. I remember one time that there was a down-hill skiing run that had a small mogul; in going over it, you would “fly” about 30 meters. But the objective was to try and not rise above the ground, because time spent in the air would waste precious seconds. On the day of the race, I was so focused that as I approached the mogul, at a speed of 100 kilometers per hour, I felt as if I was skiing at a speed of only about three kilometers per hour. As a result, I skied over the mogul with such lightness that I barely left the ground. And that’s when I realized that there is such a thing as subjective time, because quite possibly, from the sidelines it must have looked as if I was still racing at great speed. Later, I took up other sports, and I’ve experienced something similar three more times.

If, in a utopian world, everybody believed that history is only one of many possible ways of how to interpret events, how would you see the role of the historian in this case – including that of the art historian?

Quite possibly, such a profession would loose its meaning. But I invite people to try and make their own conclusions. Everyone carries within himself a very specific perception. In one of my projects, I included historically important and, at the same time, incredibly expensive paintings. And one of the works, with an estimated worth of 10 million US dollars, was propped up against a shovel. In walking around the pedestal on which the painting and shovel were placed, at one point, the back of the super-expensive painting was visible. It still cost about 10 million dollars, but none of its intrinsic characteristics could be seen – just the back of the canvas. It’s similar to looking at a clock from the side or from behind, when you can’t tell what time it is showing. I work on a miniature scale and don’t harbor any illusions that in my lifetime, I’ll be able to change this understanding of the numerous variations of subjective perception.

Accepting that historicity is slowly loosing its status as the one and only truth – how should museums change in this context? What, in your opinion, should a 21st century museum be like?

In listening to the stories of an older generation – that of my father and mother – about visiting art museums in various cities – Milan, Munich, Paris – one has to conclude that collections back then were extremely disparate. In Italy, the futurists were represented; you’d head to Munich to see the expressionists and others. Great diversity ruled. But in the 60’s, the situation changed rapidly – museums leveled off all of their characteristic differences and became very similar to one another, almost like Holiday Inn hotels. Whatever city they may be in, the guests intuitively know that the restaurant is to the left, the lifts are on the right, and so on. Yes, I think that nowadays, museums have become too predictable. And even if they reverted to what they were just a century ago, that would be a huge step forward for humanity (laughs).

I’d have to say that I belong to that lucky generation of artists that matured at a time when there was a very special zeitgeist. Artists overflowing with new ideas appeared at the same time as curators, art critics and collectors. Whereas today, the art world seems rather flat to me. Although there still are good artists, and somewhere there are talented art critics or curators, there is no longer a palpable synergy.

But there is hope that this will change?

Yes, of course, it is a cyclical process. In every century, there are two great revolutions in art.

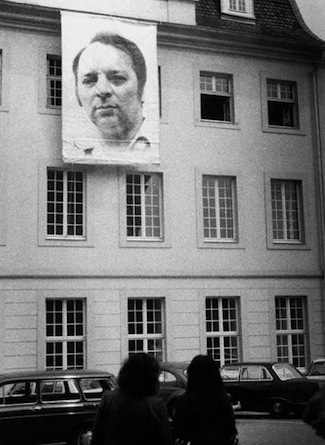

“Casual Passers-by”, Braco Dimitrijević (with long hair) and Joseph Beuys

Your art works have been displayed in places where art is usually not exhibited, such as in a zoo. Are you, in this way, trying to change the “rules of the game” of how art is viewed?

There are several reasons why I do this, but my basic interest has always been perception. And not retinal perception, but inner perception. For instance, in the project “Casual Passers-by”: seeing a huge photographic portrait on the side of a building, the viewer automatically presumes that that is some public figure, maybe a politician. The judgment is also dependent on the facade – what kind of building is it, what is the architectural context. And when you discover that it’s a stranger, a random passer-by, you must conclude that you previously made a premature assumption. If a person begins to be surprised in this way several times, then maybe by the seventh time he’ll start to think about what sort of techniques lead us to perceive images in one, definite way.

Is there any crazy idea that you have yet to realize, but would like to?

It’s hard to say, because ideas are being generated continuously. But I’d have to say that I’ve been lucky in that I’ve brought about some projects that weren’t all that easy to do. When at Berlin’s National Gallery I asked them to loan me Kandinsky’s and Mondrian’s paintings – for use in an unusual installation – the museum’s director was quite shocked, even though I was already a notable artist at the time, having taken part in bothdocumenta and the Venice Art Biennial. And even with the help of influential friends, it took six months for the museum to agree to my request.

You once said that “style is the racism of art”. But in that case, doesn’t it puzzle you that you are ranked with the conceptualists – even deemed to be one of the first conceptualists?

I’m not particularly bothered if some are aided by chronology. And it’s best to be “the first” rather than “the last” (laughs). Assigning labels corresponds to a sound mind, and as long as it isn’t done to demean, or isn’t factually incorrect, then, in my opinion, it’s rather benign.

What is your view on the internet, taking into account that it is increasingly becoming the dominant medium of communication and information dissemination – including in the field of art?

On one hand, the internet provides greater opportunity for democracy, but on the other – it’s like a floor covered in shards of broken glass, in which each shard carries just a small part of the reflection of a much more complicated whole. It’s the same way with any technology – what is important is in what state of mind you put it to use. Even a knife and a hammer can be both useful and dangerous.

What do you like most about Paris?

Paris is a city loaded with history. And the dust of history mingles with the glimmer and gold of the buildings’ facades. In some way, the Paris art scene is definitely changing – because it is no longer the most important center for art, as it once was. In the 70’s, I had a work which I recently refurbished – it’s the lecture/performance titled “The Geography of Art”. In this lecture, I have two world maps: the first is marked with dots that point out the biggest centers of art – New York, London, Dusseldorf, even Los Angeles, etc.; but on the other map, I’ve marked where potatoes are grown. There are many more dots on the second map than on the first. In comparing both maps, one must conclude that art is not like potatoes, but at the same time, it is like potatoes – because both art and potatoes are cultivated by humans.