The éminence grise of Russian art

29/10/2012

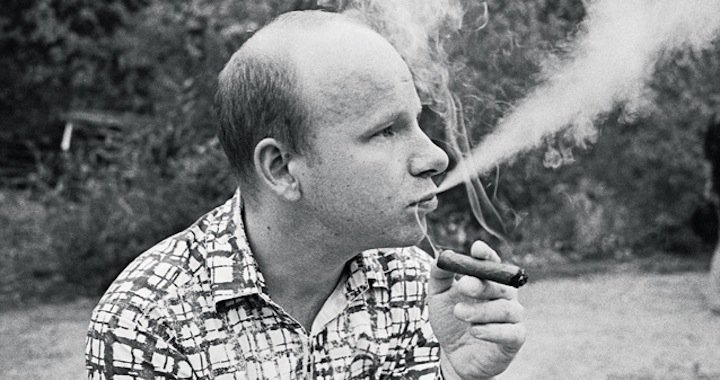

Nikolai Palazhchenko, also known as “Spider”, is a notable figure on the Russian art stage (the Russian magazine Snob ascertains that he is the art scene’s true éminence grise). He is intuitive and knows just which levers to pull at the right time. In 2007, Palazhchenko was part of the group that opened the Winzavod contemporary art center in a former wine factory. In the autumn of 2012, he actively turned his gaze to education. Under his initiative, Moscow’s Business School RMA has added a new program of study: Art Management and Gallery Business, with the participation of international lecturers and local professionals.

During the 1990s, Palazhchenko graduated from the Moscow International Film School and studied at the St. Petersburg State Theatre Arts Academy in the “experimental program”, which dealt with performance and multimedia art projects. At the beginning of the new century, he curated festivals such as Unofficial Moscow and Unofficial Capital City, among others.

In leafing through Russian media sources to prepare for this interview, I come across an article in which Palazhchenko sharply responds to a journalist’s question on how he rates the new Art Management program in comparison with other courses of study: “I piss on other programs, I’m not about to dissect them.”

Was an education in art management the missing element for a unified Russian contemporary art scene?

We realized that art is not just a market for art per se, but rather for all the involved fields. If ten years ago the art society was like a big family – only about 200 professional people worked in Moscow’s art institutions, then now it is a much larger field, with a great amount of newcomers. In addition, some of these earlier institutions have morally aged over the last ten years. There is a high turnover in personnel and as a result, the quality of work is suffering. Clear and professional standards have been dropped and the people who work in galleries, museums and auction houses no longer know what is really going on; there is no common platform anymore. Our idea was to create an opportunity for those new people who wish to work in the sector, either as employees of already existing institutions or as creators of their own business or noncommercial organisation; so that they gain an understanding of the context and a basic knowledge of the requirements.

Hence, the courses are not meant for curators only?

No, they are not meant so much for curators, but specifically for art managers, the gallery business and for those who organize and ensure art processes. Although the courses are usefull for future curators as well. Our cooperative partners are both commercial and non-commercial institutions, and that completely mirrors my notion of how the art sector is structured, because I don’t see any big differences between these two zones. The artists are one and the same, the people are one and the same, the press is one and the same and the rules of the game are one and the same. Some restrictions must be understood, such as whether you work in a gallery or a non-commercial institution. These details are the only thing that divides these two sectors. Often professional gallery personnel later take on positions in museums, or institutional personnel move to the commercial sector. That’s nothing terrible. But without some unified educational base, conflicts of interest could arise between the various art institutions and a real mess could result.

What’s behind the decline in importance of the annual Art Moscow fair these last few years? Is it a reflection of Russia’s art market as a whole?

There are both objective and subjective factors behind the stagnation of Art Moscow. The objective reasons stem, first of all, from the fact that Russia’s tumultuous economic growth has come to a halt and secondly, from the contradictious political situation. Also, a large portion of energy has shifted from the art market to the non-commercial sector because new institutions, in which the State is investing, are popping up. In terms of subjective factors, the collecting boom in Russia has subsided. Collecting is no longer fashionable, the situation has stabilized and those who really do love art continue to buy it. Those for whom it was only a status symbol have practically disappeared. In any case, they are decreasing in number.

The second subjective factor is Art Moscow’s financial situation. It is a small art fair in a city that is expensive enough. But an art fair consists of a market, business, profitability and financing, which is primarily dependent on the scale of the fair. Of course, a fair like Arco Madrid, which is gigantic, or Art Basel can afford a great deal, because as the size of the fair increases, earnings grow faster than expenditures. Therefore, the ability of Art Moscow to become a serious player in Europe has been reigned in by its size and budget.

How do you think the Russian art market will change in the future?

New dealers and galleries will appear and there will be a changing of the guard in the current generation of gallery owners. The circle of collectors has already differentiated itself greatly, with greater diversity than before. Previously, practically all of the collectors were known personally; that is no longer the case. Contemporary art will come alive in the Russian regions, and that is a huge market. An interesting way of life is arising in Perm and in the south of Russia. In any case, the story of everything happening only in Moscow will soon come to an end. That, I think, will be the main trend in the next ten years.

Nevertheless, a lot of new art spaces just opened up in Moscow in 2012. What does that indicate?

Yes, an upsurge is definitely noticeable and the State is playing a role in that. However, this type of growth is not the kind that Muscovites should wish for. Because after the crazy economic explosion in this post-Soviet city, when there was a massive change in lifestyle – for instance, the sudden emergence of sex and money into the foreground – everybody became used to such dynamic development. It’s beginning to look as if the process is slowing down again and that frightens many people.

However, I believe that fluctuations are only natural and if the tempo slows down for a while, then that gives the opportunity to finish certain details. New art spaces will always be appearing, but I think that the main issue here is not quantity, but quality. I never worry about the number of institutions. I am more concerned about how professional they are. If a city has at least one good institution with five employees, then that is surely much better than ten incoherent museums with random fifty employees each. And this issue is directly linked with the human factor: how well is the staff prepared?

Here I must mention another positive trend in Moscow – an overcoming of prejudices. In the last 15 years, Russians have begun to get their education outside of Russia. At first, many were frightened of a foreign education, especially those whose subconscious minds were still poisoned by the KGB. “What do you think you’re doing – living here, but studying over there?” But now there is an influx of European consciousness, and that is really wonderful. If something is to be changed, then there will be no need to count square meters and “heads”. It is enough to have just a few bright people who are blessed with energy, charisma, money (and the means to attract more money), along with the ability to form a team around themselves. Therefore, numbers are not the important thing; what is important is that people who have received quality educations in the West come back, or even just make periodic visits. That gives fast results to Moscow.

What about the audience? Is its size – its numbers – of no consequence?

Art institutions in Moscow have done very little to change the audience. The audience has done everything itself and in this sense, revolutionary changes have taken place. The audience has grown a hundred-fold, many times over! Exhibition halls such as Garage, Winzavod and the Moscow Biennale of Contemporary Art no longer have just hundreds, but ten thousands of visitors. Don’t forget that Moscow is the largest city in Europe. I don’t believe that this is not only thanks to some institution, but simply due to the development of society – an awareness of today’s processes. Art may not be interesting enough to be an object of property, but it is very intriguing to young people as food for thought. In addition, this sort of awareness is encouraged by the fact that nowadays, people spend a lot of time using internet resources. Also, a lot of people have their own artistic pursuits, like photography, for instance. It seems as if all of today’s young people take photographs and it follows that the creative process is not something completely foreign to them. This gives me a 100 percent assuredness that, in terms of art, everything will be alright here. And I wouldn’t restrict this subject to only the art market, which is just a part of the art world. At times it is important, but at other times, it is not a priority.

What were the main reasons for opening the Winzavod art space?

One of the objectives in 2004 was to change Moscow, and indeed Winzavod has instigated changes. It was also important to show the society and the State that such businesses are feasible. The State has money, but it doesn’t have the courage or the foresight of a business person, who makes increased earnings at the expense of both others’ mistakes and their corrections. So, the first motivator was to change the city. Another objective was the wish to support art. At Winzavod, Moscow’s main galleries suddenly came together in a much more qualitative space. They gained a larger audience, which no longer went to see something specific, but now went to Winzavod, where visitors could see several exhibitions at once. Some of the galleries acquired more space than they had before and that gave them the opportunity to expand their businesses. For some, it worked; for others, it did not. But in any case, it gave the whole city a useful impulse.

[Some changes occurred in the autumn of 2012: two galleries left Winzavod – Paperworks and Meglinskaya – thus raising discussions over whether this spelled the beginning of the end for Winzavod. The spaces, however, will not remain empty, since the respectable Frolov gallery will be moving into the space once occupied by Meglinskaya – ed.]

One should never forget the motivation and personal ambitions of certain patrons. [Winzavod’s patrons are Roman and Sofia Trotsenko – ed.] By making money through a business, it is possible to become known in public circles and to make new contacts – a new circle of people, a new level of status. And that is wonderful. In my opinion, every normal society should have such a system, so that people who make money aren’t restrained in their ambitions; so that their ego – in the good sense of the word – is interested in such largesse, that is, in supporting artistic processes.

What do you think about socially proactive art in Russia? Would it be possible for the Kandinsky Art Prize to be awarded to something that is completely removed from political life?

In my opinion, social activism in art is simply a period, a fashion, and not only in Russia, but internationally. It is a trend. My reaction to it is very normal. To me, it doesn’t matter if art is about a socially relevant theme or if it deals with social problems, or whether it is turned inward and concerned with composition and texture. For me, the deciding factor is the artist’s talent. If one looks carefully, then very similar processes are occurring in other fields; for instance, in theater, literature and poetry. The subject of a poem is not important – relationships with power, a political party’s propaganda, or love – because it is simply a joy to read well-written poetry, period.

The same applies to the visual arts. In my opinion, artists must simply be given more freedom. You have to learn to listen to an artist, not lecture him about what his works should or shouldn’t be about. Believe me, artists well get by on their own. At the same time, we should look and think about why so many artists have turned to political themes. Because art already authorizes itself in terms of what will be important tomorrow. That is why artists must be respected. We have to relate to what is going on with an extreme sense of piety, because the whole art world, the art market, all of the numerous contemporary art institutions, everything should devoted to just one thing – the artist.

Do you try to teach this to the students in your program? That art management is set up to serve the artist and not the other way around?

Our first event in the program was titled “Who Is Most Important in Art – the Artist, the Curator, or the Manager?” It was a public round-table discussion, and more than 200 people showed up to watch it. Two artists, two curators and two managers took part in the discussion. They all answered unanimously that the main person is, of course, the artist. That is also my conviction and so, those who are learning under me already know the starting point. (Laughs.)

However, this is not being understood everywhere. There is still the same old story about curators who get on their high horse and select only those artists who carry out the curators’ ideas.

In my opinion, that is only a fad. Before, this could also be seen in Moscow, but it is passing. This issue, like elsewhere, is dependent on powerful personalities. If a curator oppresses an artist with his powerful personality, then maybe the curator himself is an artist? (Laughs.) You have to react to this calmly, as everybody is creative to some extent. And no one sees this from the sidelines. All of these trivialities of the professional world – who played the greatest part, who made the most money, who slept with whom, who was using drugs – the viewer has nothing to do with these things. He is only interested in the art itself and how good it is. Over time, these trivialities are forgotten.

Why are you nicknamed “Spider”?

That’s a long story.

Will you share it?

Next time, for sure!