The Chaos of Russia’s Contemporary Art

30/10/2012

“Curator of Scandal”, “Superhero Curator” – these are just a couple of the epithets that have been given to Andrei Erofeev, PhD in art history. In 2010, Erofeev stood in front of a court of law because of two art exhibitions that were held in 2007 – “Forbidden Art – 2006”, at the Andrei Sakharov Museum in Moscow, and “Sots Art. Political Art in Russia from 1972 to the Present”, held at the exhibition hall Maison Rouge in Paris; he was immediately fired from his job at the State Tretyakov Gallery. Having escaped a threatened three-year prison sentence, but receiving a $5000 US fine, Erofeev is not even close to leaving the room known as Russia’s contemporary art world. In the summer of 2012, Barcelona’s Arts Santa Monica featured the Erofeev-curated Kandinsky Contemporary Art Prize exhibition – In an Absolute Disorder. The show was a collection of works by finalists for the national award (which is comparable to the British Turner Prize), and encompassed all of the years since the founding of the prize, i.e. the years 2007 – 2012. Dmitri Gutov, Alexander Brodsky, Blue Noses Group, Oleg Kulyik and Igor Moukhin are just a handful of names that made up the considerable number of participants.

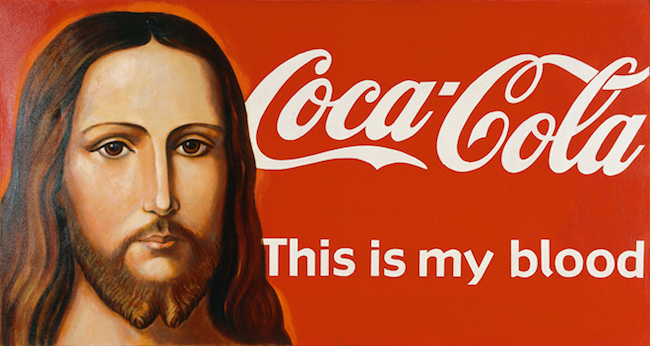

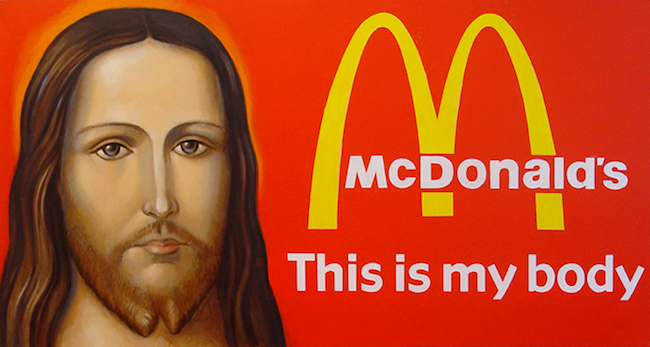

Alexander Kosolapov's works of 2001 in “Forbidden Art – 2006” exhibition

Tell me about the Kandinsky Prize exhibition that was on view in Barcelona. Did it have a unifying concept, other than its connection to the award?

I had wanted to assemble and accentuate the specifics of Russia’s contemporary art – what are its tendencies and characteristics – and also highlight the names of those artists who have had the largest impact in the last fifteen years. As a result, there were very many participants, even though there was a whole slew who were left “behind the line” – because as you know, the selection had to be linked to the Kandinsky Prize finalists. The concept for the exhibition wasn’t worked out right from the start, but rather – gradually; and I constructed it around the themes of chaos and decline. Not chaos in the sense of an explosion, like some sort of breaking of structure or order; but chaos as a slow process that is happening all over, on a wide scale, and that is uncontrollable and unable to be restrained. In addition, this process is infinitely long – a slow decline that lasts much longer than a human lifetime.

In an Absolute Disorder. Barcelona. Exposition views . Photo: www.kandinsky-prize.ru

So then, is chaos the main characteristic of Russia’s contemporary art?

In analyzing what’s been out there in the last ten to twenty years, as well my overall impressions from these years, I decided that the kind of art that is dominant in Russia could be characterized as futile – it does not play out any utopias; and even more so, it refuses any and all programs or projects. Namely, it is art that has no rational mechanism for self-control. The artist chooses not to finish the creative work to the end. He initiates the process, but thereafter, the art work spreads out, it lives its own life, and then it begins to rot and fall apart, and it usually ends up in the trash can. A similar fate has been had by many works – large installations – because in most cases, no one needs them anymore. And, I suppose that a normal person endures such a condition of entropy and collapse very badly; because the process, as I already said, is akin to a slow agony that continues long after an individual person’s death. Decline characterizes not only the material world, but also nature, societal relationships and politics, as well as the spiritual world. That’s why the exhibition was designed in three levels, namely, the materialistic, societal and spiritual levels. An average person – in terms of politics – turns a blind eye to this diseased condition; pretends not to see it. Or, he does the exact opposite – feverishly comes up with programs and irrational projects. You could say it’s happening in Russia right now: Sochi will be the first sub-tropical city to host the Winter Olympic Games; the world’s longest bridge is being built in Russia’s Far East; and Moscow is tripling in size. Our politicians are being bombarded by all sorts of irrational projects. It’s a sort of retaliation; a reply to the decline of the state and the economy.

But how does the artist view this “diseased condition”?

You see, an artist, in my opinion, views this with wonder. To him, chaos is more like a positive situation that he views lightly. In a state of chaos, it is easier for him to seek shelter and work undisturbed; for an artist, this condition is even comfortable. So, one could say that, although there was a lot of destruction in the exhibition, it was not in the sense of there being human yelling, crying and other similar emotions.

It is still essential to stress that chaos is not simply a theme. It is also the structure of the works. The creative structure. Already during the process of working, the artist has forgone the project principle, has forgone professional values, has forgone everything that could hinder his living and working. And in leading his life in this non-project condition, he creates things that are structurally similar to one another. Namely, they are in some way opened up; they are in motion. In my opinion, it is very important to understand that this kind of art is not only a concept – it is not a finished item – it is some sort of form that the artist has begun, and thereafter, it is found in a movement of change. That is an important parameter.

In an Absolute Disorder. Barcelona. Exposition views . Photo: www.kandinsky-prize.ru

How was the depiction of chaos in art illustrated in the exhibition’s material level?

At issue is life that takes place on the edge of a bottomless pit. The works of art depict survival, as well as the habitation of a tiny, homey place in this atmosphere of comprehensive collapse. In the material level of the exhibition, one could see the depiction of residency, houses, and worldly and shoddy materials – but in an aesthetically positive way. The artists attempted to aesthetically rethink it, and to change a minus to a plus. Not being ashamed of what is; not turning away in disgust as if from cheap stuff or something – but rather showing that that’s the way it simply is, and that it has its own things of interest. Practically anything could have fit in here, for instance – a sculpture cast of metal, that looks like an old rag lying in the way – that is, it is not displayed on a special pedestal. A portion of the visitors definitely assumed, at first, that it was just a regular piece of trash. The exhibition had not just installations, but also paintings; for example, panoramic paintings with scenes of demolished factories, or of bogs with fallen trees. But you can see that, at some point, the artist no longer knew how to finish the piece. The painting fades away at the spot where its creator has come to the realization that, by continuing, he will just ruin it. So, he doesn’t finish the painting. An abandoned painting. This characterizes this material level – an existential condition that is full of confusion.

What was characteristic of the other two parts of the exhibition – those dedicated to societal problems and the spiritual?

In the social level, there were struggles, conflicts and uprisings both for and against authority. The scandalous group Voina took part here. For me, it is imperative that artists not only take part in some sort of protest movement, but that they also view it with a critical eye. In the exhibit, one could see both paintings and photographs that illustrated, quite scarily, the figures involved in these protests and manifestations; it gave a sense that it was a bit scary even for the artists themselves to view. Socially pro-active art is, in some way, engaged, but it is definitely non-partisan, which is very important. That is, its aim is not to stir up and expand social drama. I’d be more apt to say that it is descriptive and critical, from afar.

The third level of the exhibition consisted of those artists that reveal themselves, firstly, through the languages of religion and faith. A portion of the art works dealt with the Buddhist concept of emptiness; another portion – with the new paganism. And then there were the works that addressed Christianity and Islam – studies on icons, frescoes, and their meanings. For example, how in Dmitri Gutov’s installation, from some sort of chaotic mass of metal – there suddenly appears an icon of the Holy Virgin. Of course, you can’t show something like that in Moscow.

What’s it like – working in the art field under such conditions with taboos that Russia (and especially Moscow) doesn’t allow to be shown, and even serves out punishment for doing so?

There is this term, “resignation” – namely, when one must simply accept the context. There is no sense in struggling; it is what it is at the given point in time. There’s nothing you can do about it at the time. However, it doesn’t hold the artist back from thinking about subjects that speak to him. If need be, he goes and works somewhere else. And then there’s the possibility that elsewhere, in another context, the artist will be inspired by completely different subjects.

Photo: aerofeev.ru

What do you think about 2012 in Moscow, when there was an uprising of sorts, as well as repression, i.e., the display of authoritative power in the Pussy Riot case? What’s your view on the possible changes – are you pessimistic, or optimistic?

It is clear that the situation in the country has hopelessly worsened. Even in terms of the final results for the Kandinsky Prize. In 2011, the group Voina won the prize. But in 2012, Pussy Riot didn’t even make it to the finals, even though they were practically the same people; or closely linked, in any case. It proves that deformities have also arisen inside the art world itself, because not only does it not support that kind of art – it doesn’t even understand it anymore, because it doesn’t recognize it as an act of art.

Maybe they’re frightened?

No, it’s much more complicated than that... because what do they have to fear? More likely, it’s an unwillingness to make an effort, to get involved – “we’ll get by”. You could say, to avoid unnecessary problems, it’s best to not get involved. And that’s a bad sign, because it indicates that the experts are becoming like the censors, like it was in soviet times – when art was judged according to strict parameters. “It offended Putin? Then it’s not good art.” If something like that was already being seen in the media environment, then the art world was still holding up. Not long ago, there was no problem in comprehending performance art, but see, now it isn’t regarded as any sort of art anymore... Something like that has a diseased effect on the development of art.

In an Absolute Disorder. Barcelona. Exposition views . Photo: www.kandinsky-prize.ru

In what sense?

By proclaiming what is – and what is not – recognized as art, the doors of both museums and galleries are shut to a whole “list”. The outcast artists begin to move into some other institutions and peculiar art spaces. A parallel culture forms – the way it was under the soviet regime. A tendency like this has appeared just this year, even though it still very faint. The thing is, the state is not ready for some sort of swift about-face right now. Because it’s not clear in which direction it should then change to. Everybody’s jumping on Putin right now, but Putin is actually just some mediocre figure; it’s not as if he were some sort of emperor now, who thought this whole thing up. No, the entire situation has grown up around him. In a sense, he’s a casualty of the situation. And this situation, of course, troubles a lot of people. But no one’s even ready for serious change. Someone’s taken out a mortgage, someone’s anxious about the state taking back everything that was privatized. People have settled in a bit; they have their own office and things like that. I have a feeling that, even though someone is rebelling, in truth, no one is ready to shout out that everything that now exists should be broken, and that we should start anew. The country hasn’t yet gone that far. And that’s exactly why the so-called “Brezhnev moral decay” is beginning to return, as well as the parallel culture that laughs it off and makes jokes – you know, like before. And in my view, that’s very bad, because it’s going to bring about the same stewing in our own juices. There are a ton of problems in all of Europe, but here in Russia, we’re going to start jabbing at each other. I think that the rise of neo-alternative art will put a strong break on the development of a unified culture. First of all, it won’t be as bright as that of the 1960’s and 70’s; it will, most likely, be much weaker. Secondly, it will be destructive to the promising talent that would have been able to shine on the horizon of all of society.

What is the assignment of an art critic in today’s situation?

First of all, a critic must describe the situation without an excess of diplomacy. The critic needs to try to understand it, and then dot all of his i’s and cross his t’s. The moral decay that I mentioned before is flourishing because of all of this uncertainty. You mentioned fear. But who is afraid? And from whom? It’s unclear. In this mess, things just get worse and they become inflated; whereas clarity would give people the opportunity to take at least some sort of position – to agree, or to not agree. This sort of clarity is lacking, and in my opinion, not only in Russia.