“I’m not an art therapist”

12/04/2013

“Art gives an outlet. It creates a safe space. I believe strongly in art therapy, except I’m not an art therapist. That’s what I usually try to say to people – I’m not a therapist, I am just a painter,” explains Rosa Ibarra, the Puerto Rican artist, who is visiting Riga as a part of the Art in Embassies program that for the last five decades has been organised in the United States Embassies all over the globe.

Born in Puerto Rico, Rosa Ibarra spent her childhood in Old San Juan and went to high school in Paris, France. Now she holds a degree of Fine Arts in Painting from the University of Massachusetts and has done advanced art studies in Paris. Her paintings mainly focus on the magnificence of women and children and she believes that the inspiration behind these art works “is born out of subtle beauties: a soft expression on a child’s face, the radiation of strength, a quiet moment of contemplation.” In addition to being a painter, Rosa Ibarra has also taken an active role in social projects – creating a children’s illustration books with male prisoners, teaching painting to recovering cancer patients and looking after young girls in a detention centre.

I understand that your father, painter Alfonso Arana, encouraged your first experiments in art. Is that correct?

I was born into a family of artists. My father was an artist and my grandmother was a writer. I discovered art when I was still a child. By then my father was already an established painter. He was giving art classes to children and I was one of the children, who took them. When I was growing up I was always in his studio. Then I went to an art college in the United States and after graduating travelled to France to work with him as his assistant.

Did you struggle to find our own signature after having such a close connection with your father?

That’s a good point. It was very hard, because I was working on his canvases. So much of my time and inspiration went into his paintings that I could not work on mine. I talked to him about it and we decided that I shouldn’t be working for him full time. By then I was already able to imitate his brushstrokes. He was commissioned to do a portrait of the governor of Puerto Rico, but, as he was so busy preparing for his own shows, he intrusted me to fill in some areas of that painting. It came out so perfect. He could not tell the difference between my brush strokes and his.

So when did you become involved in these social projects – teaching painting in prison, working with teenage girls in detention and painting with cancer patients?

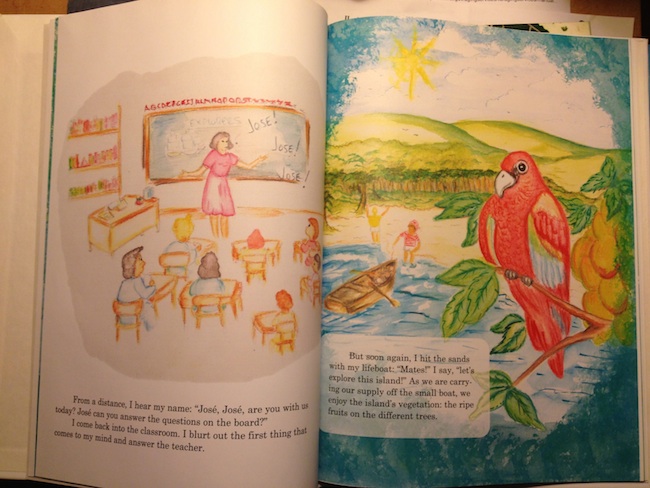

It just happened. Regarding the prison, I was invited to give a small talk. One day I visited the prison – I went and I just loved the place. There I met some guys, who were interested in painting and decided that I want to do a project with them. It was a children’s book. They wrote stories for their children and illustrated it. It was not premeditated. It was just a great experience.

Did you not feel uneasy when entering this environment – the prison?

On the contrary. When you meet people that have been detained, they are very receptive of anybody coming to them. The adults I was dealing with were already improving. They were in another stage. They wanted to better their lives, to start a new life. So when people from the outside came to them in order to help them, they were very appreciative. It was an exchange that was very meaningful. I didn’t expect it. I did this one project with them and by the end of it one of the men had decided to go to an art school. Later on I met some of them in a reception at the jail. It was so good to see these people in their new lives. They were all doing well. We hugged and felt like friends. But they do have to deal with a lot of prejudice. Once you have been in jail, people are very reserved towards you. It hurts, especially when one is trying to do better.

José’s Book: José’s Long Awaited Vacation

How close were you allowed you develop the bond with these prisoners?

You cannot get too close. There are some rules that you cannot ignore. They tell you all about it, when you go there. There is a clothing code – you cannot show your toes, for an example, because it might be a fetish for some men. (Laughs) You cannot tell the prisoners about your private life either. You can listen to their private lives, but you cannot talk about yourself. There should be no physical contact. Also, you have to count your brushes as they can be used as weapons. I have already forgotten other rules. I was, however, in another category, because I am an artist – I was not en employee of the jail. I was there as a guest. I was not paid to be there. It was just something I decided to do on my own. But as I said, that was only a project; now I work with teenagers, who are in detention.

There must be a big difference – working with men or with young girls.

Yes, the girls are difficult. (Laughs) They are very difficult. I cannot generalise, but, as the men in the prison were older, they treated you with respect. There was also a willingness to please. When there was a lady in the room, they wanted to be seen as gentlemen. Many of the girls, however, have an attitude. They don’t want to be there and they tell you that. They are only there because they have been stealing, fighting or doing drugs. Many of them are members of gangs. Some of them want to be helped and they want to do better, but there are also girls, who are waiting to get out, so that they can hit the person from before they were locked up.

So how do you deal with them?

I deal with them through art. The group is small – 12 girls is the maximum. I started drawing them and it developed into a different relationship. Now I am Rosa, the one who draws them. (Laughs) That’s why they don’t really get angry with me. I have a different relationship with them. Maybe it’s because I’m Puerto Rican and many times I don’t understand what’s going on. It’s a different culture – the gang and the street culture. Did you know that the girls are not supposed to draw stars, because that can link to a gang? They are also not allowed to wear specific colours, because some combinations might again mean that they are gang members. I don’t know too much about it and somehow they respect it. Not long ago there was a new girl in the program and the head supervisor asked the other girls to explain what their number one rule was. That’s when they replied – don’t mess with Rosa. (Laughs)

I draw them when they are angry and it makes them peaceful. Sometimes I draw them when they are sad. Many of them have children and they miss their babies. That’s when I go to them and ask, if they would like me to draw their baby.

How did it all start – you drawing these girls?

It all started with this one girl, who was very angry. The staff told me that I have to watch her, because sometimes they hurt themselves. So I started drawing her and she calmed down. That was the first time when I thought, “Wow! This works!” That’s how I started drawing other girls as well. I usually do it at times, when they were feeling strong emotions. And somehow they calm down. I guess it’s because they need to be still for me to draw them, so they must shift these emotions and relax. Then I make them pretty. (Smiles)

There was once a girl, who at first I found difficult to draw. Many of these girls don’t take care of themselves, but I need to make them pretty. It was going to be a challenge. I was really asking help from the universe. But somehow with a few lines and not much shadowing I was able to capture her. The drawing came out really beautiful. The girl was astonished. She was showing it to everyone. She loved it so much that she wrote her name next to it. She needed to put her name on the paper. That never happens.

Are they allowed to keep these drawings?

Yes. I draw them in my notebook and then I give them photocopies. Sometimes they ask me for two or three copies and they give them away to their family. Moments like these really prove that drawing is magic. The girl recognised herself. It was her – those were her eyes, her lips and her hair. It was 100% her in a pretty form. She felt beautiful.

How often do you visit them?

I am an employee, but I only work per diem – when they need me. I choose my time. I am a painter. Sometimes, when I am inspired, I cannot work there. But I am there a lot, because I enjoy working there. So, when I go there, I always have my drawing book with me, and, whenever I see that there is a situation, when one of the girls is feeling sad, angry or hurt, I draw her. It comes naturally. Of course, I can only do that when I have time, as there are days when I need to be watching the girls in a classroom. You have to watch them very closely as they can become violent. But otherwise they are really sweet. It’s a good place for rehabilitation – for them to get better and work on their problems.

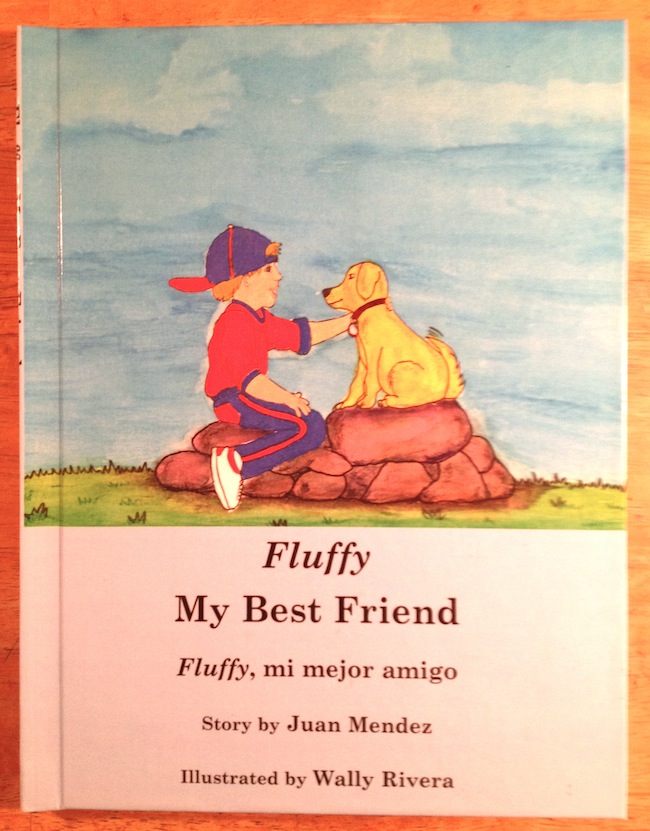

Juan’s Book: Fluffy My Best Friend

What interests you in these places – the prison and the detention centre? Why do you feel the need to go there?

I know that it’s weird. (Laughs) I think it’s the human aspect of it – I get the satisfaction and they are satisfied. It has to do with giving and sharing. I think that art is such a gift. It’s a talent. We all have our talents and when we share them, it becomes such a rewarding thing. So why not? I guess it’s has to do with sharing the talent with people, who have not been necessarily exposed to it. We have had people, who come and teach these girls how to write, so that they can put their emotions on to paper. They now write these beautiful poems. We are giving them a tool of a positive self-expression. It’s as simple as that.

In the beginning I didn’t know that it was really making a big difference. I started noticing it with the girl I was telling you about. Afterwards I started drawing other girls in other situations and it was very effective. Recently I began painting a landscape on the wall of the detention centre. The wall is located where all the girls have to stand in order to make a transition, like they do in the movies when they line up. During this line up they are facing a plain wall. So I asked the director, if I could paint the wall and she agreed. So I painted it. It is just this simple landscape, but every time I am there, when everything is calm, I work on that wall. The other day one of the psychologists told me that the staff feels the difference. That’s what art does. Even if there have been moments when the girls have their attitude, they all say, “Oh, it looks nice”. They always have something good to say. It’s amazing.

Do you think you would be doing this, if you hadn’t chosen art as your career path? Would you still be visiting these kids in detention?

Yes. I would prefer to work with women, with mothers who are locked up. I think that womanhood is so special. I think the specie continues to be because of women. I have three daughters and then I had a boy. That’s when I told myself that I have to learn that boys are also important. (Laughs) Of course, they are important, but I think that women are really special. I think it’s a special gift to be a woman in this life. That’s why I think that women would have so much to tell as well. They have to deal with so much. I would like to do it all the time, but I have to leave time to being an artist.

How do you switch from being an artist to working with the girls?

Sometimes it can be a little tiring. If I work a lot with the girls, when I come home, I need a day or half a day to get back into my space. The good thing about working per diem is that, if I am working on my paintings, I can tell them that I will not be able to work for a few days. Usually I base my schedule around my paintings. It’s not the other way around. I am an artist at first.

It is now a part of my life – I go to the market, make dinner for my children and visit the jail or the girls. It enriches me. I have also worked with the survivors of breast cancer. These old ladies are sweethearts. Often they are low-income women and they don’t speak English. They are shy and many times they don’t contact the social services to get as much treatment as they should. When we are working together, it’s a way of making them feel good about themselves. If they do a pretty painting, they feel so happy and so proud. A lot of these older ladies are holding the brush for the first time in their lives. There was this one lady, who did a beautiful painting, but then her cancer came back and she passed away. But before it happened she told me that her pride was that her grandson, who she was very close to, had her painting on the wall. He had placed in the living room, in a significant place. It was important to her. Art is good for the spirit. So it feels so food to put a little bit of that into their lives.

I also went to a place here in Latvia – we were with teenagers, who are dealing with some addiction problems, in rehabilitation centre “Strautlīči”. That was amazing. I wanted to teach them how to draw portraits, but that did not happen. I started helping them and ended up drawing their portraits. They all wanted me to draw them. It was fantastic. I did four or five portraits, but I will be going back to do the rest. We did this workshop in the morning and then they invited us for lunch, afterwards their shared their stories. It was interesting to hear them, because I had felt their pain even before I heard it. Then I just wanted to go back so that I could do them better. I want to to re-do these portraits so that they can have them forever. The kids here were very receptive.

What do you want to teach the people in these social programs?

I am just trying to teach them how to do something simple so that they can pass their time. They could also be reading or doing something else. When these kids sit down and pose for you, they become so peaceful. You can still feel the pain in their eyes, but they are in piece with whatever the reality is. So that experience of posing is something similar to a meditation – you find peace in your reality. Maybe that’s what they learn in these portrait sessions. Maybe at some point they might try to find that place again in their reality. I think that’s what they are trying to find through drugs and alcohol anyway. I just realised that. It’s interesting how we don’t plan for these things, but they just come to us.

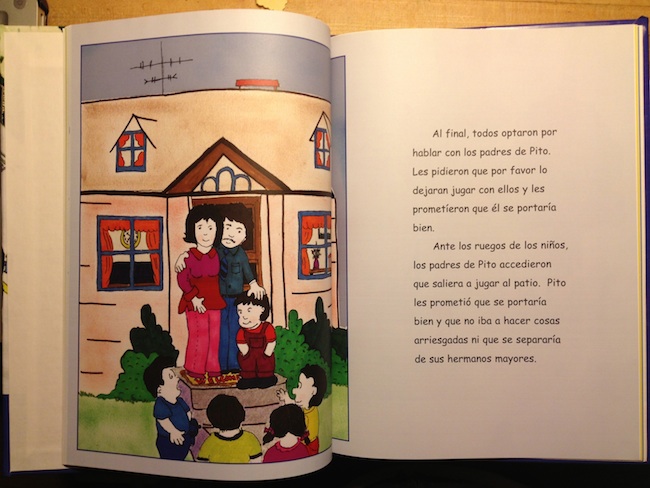

Danny’s Book: Pito, un niño encantador