Painting is not a Sacred Cow

10/08/2011

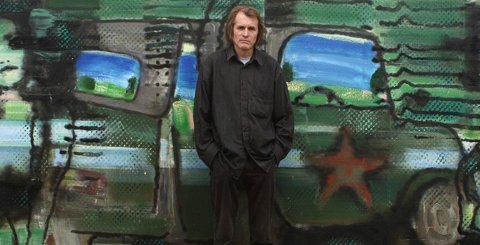

An interview with Lithuanian painter Jonas Gasiunas (1954), whose series of paintings Northwestern Wind will be on display at the Cēsis Art Festival’s exhibit Interstice in the Old Cēsis Brewery through August 14.

In Latvia, the general public first saw your works only in 2009, during an exhibit of artists nominated for the Swedbank Award, at the Riga Art Gallery. You won the award that year. But what did you do before that?

I’ve been working since the 1980s. Even before perestroika. I was born in 1954, so a pretty long time.

How did you arrive at your painting technique, which every viewer marvels at? [Gasiunas uses candle smoke and soot to draw dwindling, quivering lines on canvas.]

There isn’t anything miraculous there. Thought is important, not the technique. I didn’t chose the technique for aesthetic reasons. It grew on its own. As a form that reflects thinking. Painting isn’t my craft. Style, beauty, and narrative intrigues are only the surface; the main thing is what hides behind it. Behind it is my personal story and my trust in reality.

I’ve read in interviews that your story is about memories. How can a candle flame, smoke, and ash express your memories?

Memories always romanticize the past. Even to the extent that they turn into some sort of fairytale. It seems that a story is the truth, but with every year it changes and acquires a nostalgic form. In the end, memories are hidden in part of that truth which I want to express in painting. My doubts hide there too. Though I don’t want to have doubts, what was once real, now is no longer.

Are these memories from the Soviet era?

I’ve never thought that the signifier “Soviet” could in some way relate to reality. That was a fictitious country, a fictitious politics—everything was fictitious. The entire Soviet period is more like a Kusturica film than reality. Nevertheless, that [life] is a real fact which I don’t want to forget.

Do you turn your attention to the present day, too?

I do both one and the other. Let’s say that it’s like me flirting with the viewer. But if we analyze the theme in its entire formal size, then we must understand that the solutions are the present day. The composition, all the formal techniques are taken not from classic painting, but by my becoming interesting in the things done by designers, for instance. Or by contemplating certain stages of art history which have created new forms. I think that painting… I agree with Luc Tuymans that painting has always spoken about one and the same thing: about the time in which the person lives. You can also say this about art as a whole. Painting is an artist’s specific, individual activity, which will never be repeated.

You mentioned historical periods when new forms have been created. Do you have a historical style that you tend to turn to?

I am very skeptical about historicism as a style; I don’t like it. For example, I have painted a work called The Great Duchy, which is dedicated to a historical event. But on the other hand, it is absolutely comical. I don’t paint any romantic scenes.

What is your relationship like with expressionism, which has been more influential in Lithuanian art than in Latvian art?

It is simply a historical legacy. Fifteen years ago I was in a group of expressionists who have already become classics. When I was young, and had recently graduated from the academy (back then it was the institute), German painting left a strong impression on me—Baselitz and others. After three years, my generation and I got over our expressionism, because we understood that we had missed the train. I saw how the former grand names in expressionism, like Kiefer, conceptualized. I put aside painting for a while too, and began to do installations, objects, and video. Until I returned again to painting, when I had gotten to know a little bit about other cultures. I first saw Tuymans in Helsinki in 1995. And purely ideologically, he seemed much fresher than other artists who worked with installations. But I no longer wanted to paint like an expressionist, though individual elements have been preserved—large formats, strokes—because I can’t take a stand against myself. Yet I began to look for narratives in photographs.

An interesting combination: painterly expression and photographic impressions…

Not quite photographs. I simply collected printed images, all of the visual filth that’s in, say, the provincial press, because they have strong narratives. When they publish news, regular publications don’t tell everything through to the end. So I can process it in my own way. An image tells one thing, but I can attach my own version to it and, paradoxically, it turns out that precisely these images have give me impulses.

Right now almost all painters work with a stream of recycled images.

This is determined by life itself. It is no longer possible to be like an impressionist and find yourself in a world in which you study nature.

Is there still a place for nature studies in art?

Yes, of course. That which your eye sees is still an important factor. In the backdrop of my works, I often use direct observation. I have three-meter canvases, and I often paint backdrops in the place where I happen to be. I don’t have a stationary studio. For me, traditional artists’ studios are too small; they don’t suit me. That’s why I become like a parasite somewhere in old factories. My studio is everywhere. Right now, for instance, it’s in a former hospital, an architectural monument that they’re getting ready to restore. But for three hundred years it has been a healing place for mentally ill monks. Old rooms and five-meter-high ceilings. The arches wonderfully reflect the light, scatter it in all directions. If you stand in the middle of the room, there are no shadows. Light is the most important thing for a painter. And a buried, but still living, historical material.

From a purely technical aspect, how do you work?

I think through everything very meticulously. I don’t even begin working until I’m convinced of how it will all look.

How do you combine this contemplation with impulsive expression?

Expression itself is a mental category. I don’t hide temperament. But I choose the coloring so that it looks like a painted photograph.

Both in the Cēsis Art Festival and in the aforementioned Swedbank exhibit, one could see how differently you and the renowned Estonian painter Tõnis Saadoja use photography.

He is very talented; he reprocesses photography with a specific understanding of surface. We don’t know what he has added or subtracted from the photographs, but the light in them is particularly painterly. He doesn’t copy; he adds much of his own.

You also teach at the Academy of Art. Do your students imitate you? What do you teach them?

The department I head has changed very much over the last five years. Now, painting is no longer something clear unto itself. It is just a means for creating art. In our program the foundations of painting are taught only in the first year. In the second year students learn all the key stages in the history of painting—all the modernist styles such as fauvism, constructivism, and so on. After that they get to me; I teach new figurative art. Alongside this, students take a serious “multidisciplinary course,” which is what we call it. All the mixes that are possible by using painting and enhancing painting. Beginning with the understanding of what is collage and assemblage, and continuing with installations and video. The department has its own art historian, ideologue. He assigns students to write papers on contemporary art and introduces them to the experiences and texts of the most renowned artists.

You said that you teach figurative painting. What do you think: is a depiction of the human figure topical right now in art?

Right now—very. Because pure abstraction is very weakly connected to its time. It can’t say anything new, though that doesn’t mean good works aren’t created. Figurative art itself doesn’t hide the fact that it doesn’t even want to say something new. It changes along with reality. This is interesting, unlike abstraction. What is more, the vision of the human body has changed quite a bit. Sharper and more serious narratives are possible. New topics are offered both by feminism and by gay art. For example, the Dresden school offered a new vision of the human being, based on its East German experiences. In any event, there are perspectives. Figurative is also special with the fact that, with it, you can even depict completely awful things. But, for example, it is hard to call abstract art “social.”

Contemporary art has the tendency to infinitely expand and blur the boundaries of painting, even to the point where it is possible to call anything “painting.” All of this enriches, yet obviously a center is preserved, some unique characteristic without which painting is unimaginable. What do you think this is?

What makes painting actual as a genre: a static image. Ever since images were set in motion, like in the cinema, the view has been raised that painting must leave the stage. But everyone forget about the hypnotic effect of paintings. In order to understand, you must study philosophy. Painting visually analyzes those same questions that are put forth theoretically by Lacan, for instance. They enlighten anew the art of Rembrandt and Velasquez.

An unexpected answer. Latvian artists would definitely have answered something about color.

Color is just a means. For me, painting is not a sacred cow. The main thing for me is truth.