Painting and life are very interrelated

A conversation with George Condo, shortly after the opening of his exhibition at the DESTE Project Space, a former Slaughterhouse, on the island of Hydra

“You're mad, bonkers, completely off your head,” said Lewis Carroll's Alice in Alice in Wonderland. “But I'll tell you a secret. All best people are.” Despite the outer shell that we more or less skilfully hide under in our diverse and undeniably unique lives, we are all "the mad and the lonely". In this sense, the title of George Condo's exhibition, The Mad and the Lonely, is very apt. And who better to feel this than Condo – a painter who, in a virtuoso juxtaposition of form and color where reality overlaps with abstraction, brings to the outside a world which, in everyday life, lives mostly inside us. A world where words have little weight (because they are too limited); where emotions, feelings, memories, visions, experiences of this and previous generations rule; a world that is beautiful and ugly at the same time, where joy and horror are synchronous self-expressions; where neurons sometimes run at breakneck speed and where time is not linear. A world that is still uncharted, and which we continue to discover – constantly surprising ourselves – until the last day of our lives. A world where we are never able to answer the question: "Who am I?" A world in which the line between sanity and madness is fragile, if anything, and one in which humanity continues to be it’s own undoing as we cyclically lead ourselves towards destruction.

I look at the small-format paintings made by Condo – boisterous and slightly melodramatic in their brightly coloured frames/boxes where everything is seemingly wrong and yet infinitely harmonious – and I am reminded of a meditation teacher I went to many years ago. She talked a lot about Kabbalah, asked me to close my eyes, and brought me into a state where I felt I was in a world similar to those conjured up by Condo. "Don't be surprised," she said, "if at some point in your life, walking down the street, you see ghostly apparitions coming towards you. Not quite skeletons, but something along those lines." At the time, I couldn't quite grasp what she was trying to tell me, but now, as I watched Condo's sculpture The Triumph of Insanity (2008) cast surreal shadows on the floor of a former slaughterhouse on the Greek island of Hydra (which in 2009 was transformed by Greek collectors Dakis and Lietta Joannou into an art space – the DESTE Foundation’s Hydra Slaughterhouse Project), I understood. The moment we start to see, we start to notice, accept, understand and feel what we see – the diversity of ourselves in one and the same reality. Moreover, in one specific moment, because the facet of madness in Condo’s sculpture (or rather, in me, as I was looking at the sculpture) was illuminated in that one unique way and not in any other way – in those precise seconds of interplay between the sea, the walls of the old slaughterhouse, and the shadows cast on the floors by other viewers.

The exhibition on view at the DESTE Hydra Slaughterhouse Project from 18 June to 31 October includes a number of small-scale paintings and sculptures selected from the Condo's long-standing career. As Condo said in a public conversation with Massimiliano Gionni at the Open Air Cinema on Hydra the day after the opening of the exhibition: “The characters and paintings come from different periods of time – 1989, 1993, 2000 – selected from my personal collection. I kept them because I liked those paintings. They reflect a melodramatic mood, with each character seeming a bit lonely and isolated. By placing them in these colored boxes, I liberated them from their isolation. It felt like they needed to be freed from the miserable preexistence they originally had.” And with his characteristic sense of humor, Condo added: “It was kind of an anachronistic move. What would be the most insulting thing you could do to a minimalist? Add a figurative painting into one of their works. For a traditionalist painter, they would never contextualize a figurative piece within minimalist, box-like frames. Similarly, in my paintings, there’s this interchangeability of languages. I thought, ‘What if I took these paintings I have done and integrated them into a language they don't belong in, but made it feel natural?’ That’s how the boxes were created.”

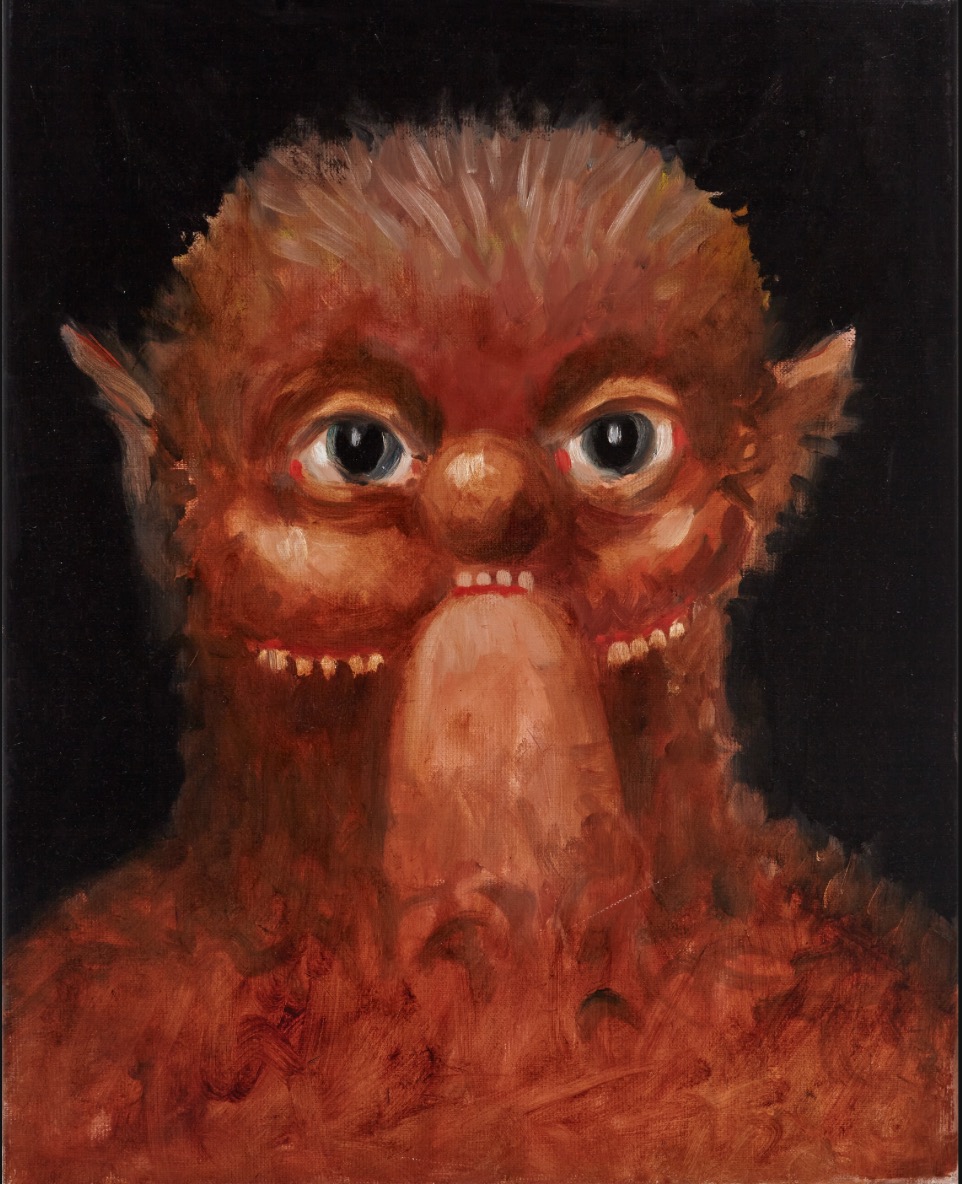

George Condo, The Mad, 2024.

Installation view, George Condo: The Mad and the Lonely.

DESTE Foundation Project Space, Slaughterhouse, Hydra.

© George Condo, courtesy of the artist and Hauser & Wirth.

Photo: Giorgos Sfakianakis.

Pursuant to Condo's signature style, the images in his work build bridges across art history – from the Renaissance and the Baroque to Cubism, Surrealism, and Pop Art – his visual language twists virtuoso loops that sometimes insidiously pull you into whirlpools of references and then, just as powerfully, eject you. At first sight, works such as Woman with Bear (1997) seem to be borrowing from the principles of Cubism in that subjects are broken down and depicted from multiple perspectives at once. In fact, however, the distorted figures in such works are composed of an array of simultaneous emotional states and are brought to life through what the artist himself refers to as “Psychological Cubism”.

“I've read a lot of philosophical writings, especially the ancient Greek philosophers like Heraclitus, Aristotle, and Plato. They were really informative about how to think and how to describe what an object is, and what being is. When I started thinking about becoming a painter in the early 1980s, I wanted to do something different. Everyone was doing multiple images – a style called New Image Painting – at the time. But nobody was combining everything into a single iconic image. So the first painting I did like that was a Madonna, and I scraped her face off, kind of like something Francis Bacon would have done. Suddenly, it was like Francis Bacon meets Raphael, and it became a new way of painting. I call them ‘fake old master paintings’ because I was thinking a lot about Marcel Duchamp and found objects. I wanted to create what I called ‘simulated found objects’. I wanted them to look like they were painted hundreds of years ago, but in fact, nobody could have painted these paintings back then because they had my name on them. (Laughs.)

“(…) I've always admired the old masters. I've mentioned before that when Warhol didn't know what to paint, he asked his mother. She told him to paint what he liked the most, which was Campbell's soup. So he painted his first Campbell's Soup can. Back in 1982, I thought about what I liked the most, and it was old master paintings. So I started with that, and that's how I began,” revealed Condo during the public conversation.

“When I was in college studying art history, I delved into the mathematical construction of Renaissance paintings, learning how they were geometrically designed to look natural. I realized that the formations you see in works by Francisco Goya or Raphael involve very complex mathematical diagrams. This understanding led me to the concept of artificial realism – the idea that realism in these works stemmed from their mathematical structures.”

“If you examine the placement of figures in these paintings, you'll see they are extremely precise mathematically. Then, of course, there's the virtuosity in painting fabrics and faces, but the positioning of figures depended on specific mathematical schematics. In 1988, I began using the term ‘artificial realism’ to describe my work.”

“To me, realistic representation is inherently artificial because if you look up ‘artificial’ in the dictionary, it means man-made. Being a realist is what I've always aspired to. A realist paints things the way they see them, not necessarily the way they look. Realist works are not just representational – they are personal. So, the idea of blending personal vision with a man-made world resonated with me. Reality exists outside our perception – a rock in the middle of nowhere exists whether we see it or not. Similarly, the people I paint exist in my mind like that rock in the middle of the ocean. When I bring them to life on canvas, they attain a kind of external existence. They aren't glamorous by any means; in fact, they are more tragic than glamorous.”

In a sense, as a mirror of the psyche and of man's multifaceted mental states, George Condo's portraits are timeless. They seem to capture a contemporary person in a specific moment, while at the same time including everything that has happened to them in a mediated and grotesque past/present dialog, thereby reminding us of the importance of empathy. This is not only considered the highest form of intelligence, but also a skill. As the philosopher Hannah Arendt said: “The death of human empathy is one of the earliest and most telling signs of a culture about to fall into barbarism.”

In a somewhat mystical and metaphysical way in which the image of the island itself and its history also play a role, the exhibition on Hydra connects us with the essence of art and painting. Moreover, in a very emotionally charged way, which paradoxically dissonates with Condo’s figures. "I think it was just the idea of keeping one’s spirits high," he says with a laugh.

In answer to Massimiliano Gioni’s question on what meaning does painting have, Condo says, “I think that painting serves as a kind of metaphysical exercise for our minds, allowing us to piece together what we think we see. I believe that the paintings themselves tell you about the person looking at them, not the other way around. When you observe a painting, whether it's a Van Dyke or a portrait of George Washington, you imagine what's on their mind, right? Whether it's a realistic portrayal of a woman or a man, you ponder what might be going through their minds. But if you really think about it, there's nothing actually going on in their minds because they're just paint on a canvas. It's like trying to understand what a rock is thinking – there's nothing there. So what we perceive as their thoughts is actually our projection onto them. I think painting helps us maintain our perception and activate our senses by engaging with art.”

My conversation with George Condo took place a few days later, over Zoom. Condo was now in Monaco and wearing a sweater... Greece's +40ºC has become an abstraction and a reality at the same time.

Installation view, George Condo:

The Mad and the Lonely.

DESTE Foundation Project Space, Slaughterhouse, Hydra.

© George Condo. Photo: Giorgos Sfakianakis.

In a way, your paintings are a lesson in emotional intelligence. One can find in them all the basic emotions defined by Paul Ekman. At the same time, they show us the infinite depth of the human psyche. They remind me of the ocean; we only know a little about the world deep down there. There is a big question of whether we will ever be able to understand the human psyche, but perhaps art is a way to get closer to this understanding...

I would agree that art is a window into the human psyche, and that the metaphor of the ocean is somewhat related to the subconscious. We don't really know what's 100% in there because it's been with us since we were children. When we finally become adults, we are somewhat preprogrammed to behave in certain ways. Then, we make conscious decisions based on our knowledge gained from reading, classes, and other experiences. When you're a painter, you try to experience your inner emotions, even if they're not entirely your own and may feel like the emotions of others. If you're a person who is very magnetic – not to the other world or to everyone else, but as a magnet for other people's emotions – those emotions stick with you. They linger in your brain along with the way things look, and you start to transcribe your emotional picture. In this case, as shown in the exhibit on Hydra, it's portraiture inside a modernistic presentation. So, I do think that you can never truly know someone's thoughts, even if a doctor were to dissect your brain. They may understand the physical matter but not the mental matter. Let's put it that way.

In your work, you like to make bridges between art history and the contemporary. I had an interesting discussion once with Professor John Bargh of Yale University, who has devoted his entire 40-year career to researching human consciousness. He says that we are simultaneously living in all three divisions of time at once – the past, the present and the future – and within each of them is a hidden part, as in a hidden past, a hidden present and a hidden future. Is this something you want to show with your art as well?

Especially on Hydra, I wanted it to represent the past, present and future. I wanted people to get a sense of ancient mythology, a kind of transition from Greek sculptures and their proportions to the Renaissance and Baroque periods – where they became obsessed with those proportions – and then to Neo-Classicist painters. Then, moving into a more Romantic period where things are freer and more realistic rather than just representational, and finally, liberating these ideas in a modern, colorful and polychromatic way.

And the combination of those two time zones, for example, the time zone of traditional painting and, let's call it the time zone of minimalism, creates a future where anything is possible. The possibilities of the future are unknown; it’s a hidden present and a hidden future.

I also think the slaughterhouse itself is a metaphor for the world today. We live in a world full of pain, anxiety and terror, much like the experience animals have in a slaughterhouse. We're living like those animals in today's political environment.

I also think the slaughterhouse itself is a metaphor for the world today. We live in a world full of pain, anxiety and terror, much like the experience animals have in a slaughterhouse. We're living like those animals in today's political environment.

But even within that, I wanted to show something uplifting and positive in this moment in time. I believe art is one of the few things that brings hope to the world.

George Condo, The Triumph of Insanity, 2008. Installation view,

George Condo: The Mad and the Lonely. DESTE Foundation Project Space, Slaughterhouse, Hydra. © George Condo, courtesy of the artist and Hauser & Wirth. Photo: Giorgos Sfakianakis.

As we can see in cave paintings, art as a form of human expression has been with us since the very beginning. Could one say that art is a primordial need – a source of unlimited creativity and a universal communication tool without the boundaries of language and race – and something that we desperately need for survival?

Yes. My theory, and it's a theoretical idea, is that most of the works done in the caves – like in the caves of Altamira, Lascaux and elsewhere – probably a lot of the art was made by women, “cavewomen”, not cavemen. They always call it caveman art, but I think it's more probable that the men were out hunting and the women were responsible for the representation of the hunt. It may very well be that all the cave drawings were made by women. It's not something that you ever hear about because nobody knows who did what. But if you think about Louise Bourgeois and some of her drawings, the red drawings look a lot like the kind of cave paintings that you see sometimes. We don't know everything that happened many, many years ago, but we do know one thing. We know that in time (which I see as a nonlinear kind of situation – I'm not a big believer in chronology), if something didn't happen, no matter what it is – if a coconut didn't fall off a tree in 1410 – maybe the whole world would be different today.

Because everything that ever happened in the past led to where we are today. But those are not necessarily the important things, you know? It's the smallest things. If it hadn't rained for one day in 1904, the world could be a completely different place. So I feel like, making an exhibition on Hydra – if I hadn’t done it, who knows what would happen to the planet in that sense. It's not about the fact that I did it, but rather that it happened, and so many people came out to see it. I think this doesn't say anything good or bad about the exhibition; it just simply says that it happened. And that's a real fact. There are so many facts we don't know.

You know, someone said to me at the opening in Hydra, "I'm going to ask you a really dumb question. I'm sorry, but what came first, the chicken or the egg?" I replied, "Well, obviously, it was the chicken." And she said, "Really? You don't think it was the egg?" I said, "No, I think it was the chicken." She asked, "Why?" I answered, "Because I believe the chicken was a kind of animal that evolved from something that came out of the water. It evolved into the form of a chicken, and other creatures that came out of the water evolved into a rooster. Then they got together and laid the egg."

I was telling Dakis (Joannou) about this, and he said, "It's like people saying we evolved from monkeys, but actually, the very first species of humanity probably came from the water." There's so much we don't know about the idea of water, you know? But back to your first point, it could be the origin of human life and it could be the end of it, if the water keeps rising and covers the world again. Those are the two unknown frontiers: space and the ocean.

Land, I think, has been pretty much explored with drones, airplanes, photography, and other technology. But we still don't really know the darkest depths of the ocean, nor do we fully understand the farthest dimensions of space. The idea of past, present, and future isn't that different from concepts someone like Stephen Hawking talked about in his ideas about space. Is space four-dimensional, for example?

Anyway, that's what I like about the boxes in my exhibition. They are four-dimensional. There's a kind of four-dimensional box with sides, a back, and a view, which is the three-dimensional painting inside. That makes it four-dimensional.

It's interesting what you said about the choice of whether to make this exhibition or not. That choice is always there. There were probably obstacles as well, and it could have either happened or not. But finally, it did happen. It has brought real joy and happiness to people; it has given them something to think about, and has created a vibration and resonance that still lingers with the audience and the place itself. In a way, art is spiritual, though not in a religious sense.

Yes, I feel as if everyone I saw – there were so many people – was smiling and happy. The characters in the paintings seem to come out of novels or stories we've read in the past. They form a constellation of cartoons and humans using an interchangeable language of painting from various time periods, all connected to create a single portrait. This portrait expresses externally what's happening internally.

The internal world of our emotions is invisible, so representing a person who is crying or laughing is complex. One person can be laughing and crying at the same time. They might put on a smile at a funeral not because they find it funny, but because they want to show sympathy. It's about empathy, understanding other people's emotions, and being empathetic towards the human race. That's why there's not really a portrait of anyone that anyone knows.

It's about empathy, understanding other people's emotions, and being empathetic towards the human race. That's why there's not really a portrait of anyone that anyone knows.

That was one of the things I was talking about with someone regarding Guattari. When Félix came to my studio, it was just a room full of portraits. He said, "I don't think there's any other painter who ever did portraits of people who don't exist. I mean, everyone in a Rembrandt or a Picasso is either Marie-Thérèse, Dora Maar, or Françoise Gilot...whoever. But in your paintings, there are nobodies – they're not people that actually exist." He asked, "So what are they?" And I said, "They're a picture of the external representation of my internal emotions combined with my technical fascination with how paintings are made." Because I'm fascinated by the way paintings are made, I like to study them and think about what's the first thing the artist did on a canvas and what's the last thing. If you can ever figure it out, that is, because sometimes in my work, the part I begin with and that I think is really great, ends up just sticking out. I then realize that if I take that part out, the rest of the painting comes to life. So I think to myself, I'll save that part for another painting someday and just knock it out, and then the whole painting comes to life.

Installation view, George Condo:

The Mad and the Lonely.

DESTE Foundation Project Space, Slaughterhouse, Hydra.

© George Condo. Photo: Giorgos

Sfakianakis.

It's often like that. It's like falling in love with someone and thinking that's how it's going to be for the rest of your life. But after seeing them and being with that face on the canvas for so long, you realize if you just took it away, you would see life in a different way. So painting and life are very interrelated. I think that's what people can understand – that there's not really a distinction between art and life.

Even if a painting doesn't feel like it's going to live forever, I think they can have an eternal life, you know. We can never be bored of a painting. Every generation will be fascinated by paintings done in the 17th century. I mean, they're going to look at a Caravaggio done in 1604 and think, "Unbelievable, the use of light and shadow." What he was able to create was this theatrical experience. Like you said, it wasn't religious; he was using real people to play the roles of religious characters.

Even if a painting doesn't feel like it's going to live forever, I think they can have an eternal life, you know. We can never be bored of a painting.

In a lot of ways, I'm using imaginary characters, kind of like those from literary sources. Like, a million actors have played Lady Macbeth, and a million people have read Balzac. These characters seem so real, but they don't actually exist. It’s sort of paradigm of reality and existence, you could say.

For me, it's also interesting how a painting starts – does it begin with the first brushstroke, or is the brushstroke just a final action that makes it physical or real?

It just starts where it starts. It's like when you jump in the water and start to swim; you know you don’t want to drown. You just take a brush and go to a canvas. I follow my hand, and I believe my hand follows my mind. So I don’t start with a set thought because I don’t want to know what I’m doing. I want to be lost in a jungle and find my way out in the clearing. I like to be in a painting where I have no idea where I’m going or how I’m going to get out of it. The more complicated they are, the more interesting they are to me.

In a talk with Massimiliano Gioni on Hydra, I was talking about music. I was thinking about, for example, jazz and someone like Thelonious Monk. He intentionally make the most complicated chord changes, maybe three chord changes per measure. Each measure might have three, four, or five chord changes, modulating from major to minor, then suddenly shifting to a completely different section. The more complicated those chord changes are, the more masters of improvisation enjoy it because they can showcase their skill navigating through them. I mean, they can improvise over those chord changes, whereas in classical music, you have just as many technical chord changes, but you can’t improvise. You’re not allowed to have improvisational sections. You have cadenzas, where composers like Sibelius leave a section for the violinists to come in and do a cadenza. At that point, they can improvise a little, but most of the cadenzas are worked out in advance.

George Condo in conversation with Massimiliano Gioni. Hydra. Photo: Arterritory.com

In jazz, someone like John Coltrane would take a song like My Favorite Things, and everybody knows that song. He played it from the first time he recorded it until the day he died. He played it at every single live concert, and each time, other than the theme, he improvised everything else.

And that’s what I like to do. I like themes and variations. When Bach wrote the Goldberg Variations, there was a motif, and each variation developed from that simple motif. With someone like Beethoven and the Diabelli Variations, you have just four notes twisted and turned in many ways. You can take 12 notes and organize them in an infinite number of ways.

With painting, it’s the sense of infinity that comes along with it. It’s not finite but infinite. Hegel talked about positive and negative infinity. He said positive infinity doesn’t have the finite aspect, whereas negative infinity starts and stops, becoming finite. Positive infinity has points leading out into endless space. I think of art as states of mind that lead to an endless journey. You want to keep the mind active even after seeing the work, so people go home thinking about it.

With painting, it’s the sense of infinity that comes along with it. It’s not finite but infinite.

Like, you can never figure it out when you look at a Vermeer painting such as Woman Reading a Letter. It’s so beautiful. There are many beautiful things happening in it, but you keep wondering, what is that painting truly about? Is it about the way he painted? What he wanted to paint isn't really just about the woman with a letter – what did the letter say? The light coming through the window, how it affects the atmosphere in the room – all these different things make you think. They’re kind of metaphysical, like De Chirico's idea of tangible things juxtaposed irrationally. Everything is extremely rational in Vermeer, yet completely imaginary. It’s like a dream; you can’t fully understand it.

I'm curious – have you ever experienced synesthesia, especially coming from a musical background and having music as a constant presence in your life? Wassily Kandinsky had it and wrote about it; he literally saw colors when he heard music and heard music when he painted.

I never did. Personally, I know about it. I think Vivaldi was one of those composers who was very much into synesthesia. You know, like, certain chords represent certain colors. And certain musicians, when they play notes, see sort of passages of color. But in terms of painting, I work with color, and I work with the idea about how to create black. Is it blue, brown and green? And then adding some other color to get 20 different shades of black, you know, or 50 different shades of black or 50 different shades of brown. I can't be bothered with the idea that brown represents this chord, or black represents that chord, or white or green represents this or that. I can only think about them in terms of spatial placement. So it's a kind of spatial relation that I'm more concerned with – the use of color in relation to other colors.

So, for example, if I want to put purple and orange together, I might mix a little purple and orange in another place in the painting so that the harmony of the painting will somehow come together. It's very much about harmony and dissonance. I think you need dissonance in music in order to create relief when it becomes harmonic and melodic. I'm thinking of Bach again, and his violin piece for a chaconne, where there's a moment when it changes from minor to major. At the point where the minor key starts to converge, and major notes are introduced, it sort of slips together like that. And then, the next thing you know, the entire passage is in a major key. I think it's in A or something; it goes from B flat to E. Then, again, the same thing happens – a B flat suddenly starts to seep into the major key. It ends in a very triumphant, flourishing way, almost flamenco-like. It's kind of based on the idea of a flamenco motif. I think there's a lot of beauty in the idea of dissonance and harmony.

With painting, in order to create dissonance, I think Picasso was amazing at it because there were so many disturbing aspects in his paintings. But somehow, he was able to harmonically make it cohesive, and I learned from that. It wasn't so much about cubism or his theoretical ideas about bringing negative and positive space together and fusing those two elements. It was more about how to work with positive and negative colors and dissonance.

With painting, in order to create dissonance, I think Picasso was amazing at it because there were so many disturbing aspects in his paintings. But somehow, he was able to harmonically make it cohesive, and I learned from that.

The interesting thing is if you take Picasso's rose period, for example, it's almost more sad than the blue period. Even though rose is a color you’d think is happier, the characters are despondent harlequins, or leftover figures from some aspect of humanity. Whereas in the blue period, everybody's in blue – they're either absinthe drinkers or people shivering by the water. It all makes sense. But with a color as beautiful as pink and rose and those variations, why is everybody so depressed? (Laughs.)

Actually, I wanted to ask you about Pablo Picasso. He once said, “Art is the lie that tells the truth." Is there such a thing as a “lie” or “truth”? Maybe both of them are just different aspects of the underlying reality?

I think so. I think they are. I think the art is the truth, and life is kind of a lie, in a strange way. That they lie to you as a person, as a human – they make you believe in a sort of everlasting life in the afterworld. Or they make you believe in certain things, depending on what kind of religious background you have. They teach you things about life that are not really true. Like, you might go to college and study chemistry, but you come out of college and you get a job working in a restaurant. You know, it just doesn't work over time with this issue.

But with art, it's really the truth. It's like, what you see is what you see; what it is, is what it is. There's no changing that. It's not going to transform from a small painting into a large painting. It will remain a small painting for its entire existence.

With art, it's really the truth. It's like, what you see is what you see; what it is, is what it is. There's no changing that. It's not going to transform from a small painting into a large painting. It will remain a small painting for its entire existence.

Is being an artist a profession, or is it an inner or cosmic calling to which you cannot say no?

For me, it's not a profession. It's the only thing I know how to do right. I mean, I can do other things – I can write about my work, I can explain it. But when I would show my writing on art to somebody who is a real writer, like Allen Ginsberg, he would look at it and correct the grammar. He'd say, "You can't say it like this, it's grammatically incorrect." That's when I realized I'm not a writer; I can write, but it's not correct in terms of what a writer would do.

But when painters look at my paintings, I don't think they can say, "Oh, that shouldn't be green, it should be red," or, "That shouldn't be pink, it should be orange." So that's what I can do. I feel fortunate that I can make a living as a painter, supporting myself through my art and continuing to paint.

But I've been doing it since I was a child. When I was young, I once drew a crucifix after leaving church one day, around age three or four. My mother found it quite morbid. She said, “My God, you have such a morbid sensibility.” It depicted Jesus on the cross with blood and a stained glass window behind him. It wasn't hyper-realistic, more like a Baselitz, to tell you the truth, but definitely not a stick figure. After that, I became really interested in drawing. I used to go fishing with my brother, and my mother would ask me, “Can you draw me a fish?” So I was always drawing; it just came naturally to me.

Studying music felt less natural because it sounds easy to the ear. When you listen to Mozart, you think, "Oh, I could just sit at the piano and be good." But when you really try to catch on, it's not natural; it doesn't happen that way. You have to follow the route. I wanted to understand music from the perspective of being able to read it, but I knew I could never play it.

When it came to painting, I could understand how by reading a lot of books about technique, starting with books on pigments and colors, and learning about how certain artists made their paintings. I could transpose that information or the philosophical concepts into how to paint. But I couldn't learn anything about painting from just trying to be representational or copying photographs. It's very difficult for me to copy a photograph; I'm better at making things up. Whatever comes easiest is best, is what I find.

It's interesting that you mentioned your first drawing. I read in one of your interviews that your mother kept it, and sometimes you include it in your exhibitions.

She did. It was funny because she kept all of these things. When I had the exhibition at the Louisiana Museum and with The Phillips Collection in Washington, I decided I could probably show those drawings. I don't think I got any better as a painter or as an artist. It's not like I became a better artist the more I painted. When I see the paintings I did in the 70s, and the drawings I made in 1970 when I was still living at home...now the Morgan Library has bought two of them, and I think they somehow lead to where I am today, you know, in art. Maybe some of the things I did wrong brought me to where I am today.

Laura Hoptman, who contributed to the catalog for your exhibition at the Hayward Gallery in London in 2011–12, said: “For Condo, ‘abstract’ is a verb; rarely, if ever, is it a noun”. Is “real” a verb, too?

I think it's an adjective. That is what I would say.

The beings in your paintings are often baring uneven and/or crumbling teeth. Are you, in a way, confronting us with the reality behind those Hollywood smiles we all fake in our lives?

I think reality is abstract, you know, to a certain degree, and it's based on an individual's perception of the world. If you look up the word "reality" in the dictionary, the definition is that which is external to us, independent of our perception. So, in other words, even if we can't see a zebra in Africa, we know it exists. It's real. This means that there are things out there – monkeys in trees, zebras in the Serengeti, and elephants in the wild – we know they exist. That's reality.

I think reality is abstract, you know, to a certain degree, and it's based on an individual's perception of the world.

But when it comes to painting, that's why I talk about it being artificial reality. Artificial means man-made. So, the idea of a sort of man-made reality is what I think painting is. And because we're able to alter it to fit our own concept of, say, a composition. A lot of art is ultimately about composition, color, form, and those kinds of things. There was always that question; even someone like Mondrian was talking about form versus function and these kinds of things. But I don't think there's such an argument, really, because I think the function of form has to do with design, furniture and architecture. In painting, I think it's freer. It's a more free world. It's an independent world that is, again, empathetic and embraces any culture, any kind of community in the world. All of them, no matter who they are or where they come from. Every child even begins by scratching drawings on paper, and people in every country in the world make paintings.

I think in today's world, it's more inclusive in the sense that people don't say, "Oh, that's a painting by someone in India," or, "That's a painting by a woman," or, "That's a painting by this person or that person of this race or that race." We're breaking those barriers now, and it's just about getting more art from different cultures and different communities in view. How the critics discuss that is where the politics of the discussion come into play. They're walking on a tightrope, like circus art; they don't want to fall or make a mistake in how they describe the quality of the artwork. At this point, nobody's taking a qualitative position on works from all these different diverse communities. When it was all a white man's world, it was easy to be qualitative. But now that it's an everyman's world, it's very different to be qualitative. You can't say, "Oh, those were the worst paintings I've ever seen in my life," because then you're not talking about the paintings anymore – you're talking about that community or that country.

We're breaking those barriers now, and it's just about getting more art from different cultures and different communities in view. How the critics discuss that is where the politics of the discussion come into play. They're walking on a tightrope, like circus art; they don't want to fall or make a mistake in how they describe the quality of the artwork.

It's becoming a political discussion in art criticism, a subliminal political position. I don't have one personally because I don't care about it. I just think whatever anyone wants to do, they should do. And I think that it doesn't matter if it's art or if it's... I don't care... a dishwasher.

Also, the people and things I paint – I don't care who they are. There are some painters that make every person look like a fashion model; every woman has to have a certain kind of body, every man has to look a certain way. In my paintings, it's anything...it can be a garbage man. I like the idea of Bruegel and earlier painters, who painted beggars, thieves and lowlifes. Painting the so-called high life isn't very interesting to me. It's one thing to live that way, it's another to paint it. I think by dignifying people who drive taxis, take out our garbage, or do the simple things in life, we can bring them to a level where they are appreciated by those who are sort of self-entitled. It's a more empathetic approach to art, let's call it.

I think by dignifying people who drive taxis, take out our garbage, or do the simple things in life, we can bring them to a level where they are appreciated by those who are sort of self-entitled. It's a more empathetic approach to art, let's call it.

George Condo, The Satyr, 2009.

Oil on linen. 51 x 40.5 cm.

© George Condo; Courtesy

of the artist and Hauser & Wirt.

The discussion about whether painting is going to die or not is equally absurd. Painting has been with us since the beginning, and it can't simply disappear. We're just trying to put everything into boxes.

It's funny, the idea that painting is dead, as Baudrillard once said. Nobody cares about what he said. You know, nobody cares about painting being dead. If painting were dead, they would take them out of all the museums around the world, bury them, and give each painting a funeral ceremony. A nice little eulogy for each painting, saying, "Now we bury this painting, and we place a gravestone here for Rembrandt's self-portrait, here for Guernica...here once stood Demoiselles d'Avignon, now buried in Avignon." You know, the idea that painting is dead is ridiculous. It’s “dead” from whose perspective, you know? Dead from the mind of one person, or maybe just that person's mind. Whoever thinks painting is dead must be brain-dead.

You know, the idea that painting is dead is ridiculous. It’s “dead” from whose perspective, you know? Dead from the mind of one person, or maybe just that person's mind. Whoever thinks painting is dead must be brain-dead.

Is a painter a lonely person? The title of your show on Hydra is The Mad and the Lonely. When painting, you spend most of the time alone in front of your canvas. You don't have a pile of assistants.

Well, I do have assistants around me, but they help with different things, like phones and other tasks. Sometimes they move canvases that are too heavy for me to lift; my shoulders aren't good enough. I don't want to risk injury while working; I used to lift heavy things and sometimes ended up injured. So now, I avoid doing that. I don't mind talking to my two assistants, but I never let anyone touch my paintings. No one ever paints on them. Artists like Giacometti, even Rubens, they needed assistants because they took commissions. Since I don't generally take commissions, I don't really need assistants. I wouldn't say, "You do the body, I'll just do the face," or vice versa. I create and paint everything myself; it's something I feel privileged to do.

And I really enjoy cooking a lot. I prefer cooking myself over going to restaurants. Let's put it that way.

I will put it this way – as a painter, do you often feel lonely?

Not as a painter, more sometimes as a person. Like, my two daughters live in New York. They live just down the street and I only see them once a week. They don't call me enough. I wish they would call me more, but they write to me all the time. And they come over for dinner and we have holidays together. We're very close. But you know, then when they want to move in with me in the countryside, they move in and I can't get them out. But then there's a moment when you just have to say: Okay, guys, I want to be alone now, I want to paint. (Laughs.)

So, I think mad would be in the sense of madness, not anger. You know, I think that The Mad and the Lonely is the title because I thought this is a world of madness at the moment. And also, it's quite lonely as a painter when you're more well known because wherever you go, you don't want to go there anymore. People say: “Hey, George, I saw your exhibition,” or you go to a restaurant in New York City and people come over with their cell phone, saying, “I have this painting of yours in my bedroom,” and I say okay, great. And then they say, “Isn't this the best painting you've ever made?” And what am I supposed to say? No, that's the worst one I ever made. It's like you become isolated as you become more popular. So it's more of a state of isolation that I find myself in, and I’m more isolated than I used to be. I used to be able to just walk around and be anonymous, you know, and nobody knew me. But now I can’t even go to the grocery store – some lady in line will say something like, “Oh, hi, George Condo. I met you at (such and such a place) in 1996, remember?” And I don't remember who they are. I'm not good at placing faces with people...and also names. You know, some people can remember everybody's face and everybody's name, but I am not so good at that. If I never really talked to them before, if they were just somebody who came to my exhibition, I don't remember them the way they remember me. I don't ever remember my own name sometimes (laughs).

© George Condo.

So, was the question of acceptance important for you in your life?

Yes, it was very important. Growing up, I had two brothers and two sisters, and we were all raised in a very traditional way. My father was a calculus and physics professor, and my mother went to medical school but then became a registered nurse. Everything was about going to college and getting a real job afterward. But I just didn't buy into that. By the time I reached college age, I had already made so much art. I wasn’t going to go there and unlearn everything I had taught myself and everything I had read.

When I got to New York and started making my paintings in the city, and when Basquiat told me to move there, and when Warhol and Keith Haring bought my paintings, I felt a huge sense of acceptance. Collectors like Don and Mera Rubell, who were looking for the youngest, newest thing, were buying my work. The critics were a bit negative – they tried to describe my work but couldn’t. I think they had limitations in understanding and couldn’t figure out how to contextualize me. They wanted to put me in a box, but I didn’t fit into any of those boxes.

But the artists appreciated my work. Roy Lichtenstein and James Rosenquist loved my paintings. To be accepted by the artists – that’s what I wanted. I wanted to be an artist’s artist. I didn’t care about being a critic’s artist. As long as the artists liked my work, I felt accepted. When collectors bought my paintings, it allowed me to buy more canvas, more paint, and pay my rent. I didn’t have to get a job. I could live as a painter and live my dream.

To be accepted by the artists – that’s what I wanted. I wanted to be an artist’s artist. I didn’t care about being a critic’s artist.

My family was very supportive. My parents were really happy about it. They got to see that I was making a living. When I first got to New York, I would say, "I have no money, please send me something," and they would send a card. I would open the card hoping to see something, and it was like $10 with a note saying, "I hope this helps."

I remember them coming to some of my very first openings. I looked over in the corner and saw my dad talking to Andy Warhol. They were talking for about ten minutes, and I was almost going to say, "Stop talking to my father." I thought he might say something embarrassing. But my dad later said, "You know, I really liked that guy, Andy Warhol. What a nice guy he was." I asked what they talked about, and he said, "Well, he had your catalog from Barbara Gladstone. He said he wanted the exact same essay in his next catalog, just change the name from George Condo to Andy Warhol but keep all the words the same." (Laughs.)

Flying back from Athens, we were experiencing strong turbulence while I was reading about your upcoming show at the Musée d'Art Moderne in Paris in 2025. You are going to exhibit there also rarely seen works from the period from 1987 to 1990, when you were losing one friend after another – Basquiat, Haring, Warhol… They were called The Unexpected Nightmare Series. Was that how you dealt with your own existential horrors? We all have them, don't we?

Yes, well, the show in Paris – if we're lucky and the Morgan Library lends the works – will go back to the seventies. We'll go all the way back to early works on paper and maybe one or two canvases from when I was still living at home. It was a wonderful time living at home because I had never heard of the art world. I didn't know anything about an art world. When I first got to New York, I just wanted to be part of the art world. But before that, I didn't even know there was such a thing. I just thought there was art and there was making art, but I didn't know there was what we call today an art world.

And the moment when Jean-Michel Basquiat died... You know, he had been in my apartment in Paris. He made a beautiful drawing for me. We watched some VHS tapes I had on Jimi Hendrix and Miles Davis. Keith Haring was using my studio, and I was living at the hotel. Andy Warhol lived uptown. I had worked as a kid for him, but I never told him that. Then, later, he became a friend. And all of a sudden, all three were gone…

I remember Bruno Bischofberger calling me to tell me the news about Jean-Michel. I said that's terrible; I can't believe he did that because he was in good shape and off the drugs. But I guess he went back and took as much as he used to, and it killed him. And with Andy, he went to the hospital and never came out. And Keith, he already had a very bad case of AIDS. It took a long time for it to develop to the point where he started getting big patches. He got very, very sick in New York. He was in bed and couldn't speak anymore. I tried to go back to see him before he died, but I was on the plane, fell asleep, and when I woke up, we were landing in Paris. I thought we were going to New York, but the plane had to turn around because something was wrong. When I got to Paris, I called Julia, his studio manager, and she said, "Well, Keith died today." I missed him. I would have seen him the day before he died just to say goodbye. He couldn't speak, but I could tell him, "Keith, I love you," and stuff like that.

I remember Bruno Bischofberger calling me to tell me the news about Jean-Michel. I said that's terrible; I can't believe he did that because he was in good shape and off the drugs. But I guess he went back and took as much as he used to, and it killed him.

It was a very sad, dark moment for me. It was interesting because after all that had happened, I got married in 1989. And then when I had children (I had my first daughter in 1990), it was like they replaced, in a different way, the sadness of losing my best friends. Having children took me in a new direction, and I wasn't so sad anymore. Before that, I was very disturbed. Felix Guattari died not long after, too.

It was fun with the kids because when they were young, they would come to the studio. They'd ask, "What color are you going to paint the background?" And I'd say, "I don't know, what color do you think it should be?" One would say purple, and the other would say blue. I'd say, "Okay, maybe I'll do a kind of blue with a little purple, I'll mix the two." They'd respond, "That's a great color, Dad!"

I'd be painting, and then they'd come running down the stairs when they were five or eight years old, yelling, "We want to see the painting!" They were like my audience. That was nice. It was different than having friends who were painters.

I think I was in my late twenties around the time [my artist friends] died. Jean-Michel was two and a half years younger, and Keith was one year younger than me. It was terrible that they died so young. They were so talented. There were so many brilliant things that happened in daily life with them. We didn't have cell phones or computers back then. You'd run into them in bars, on the street, or call on a house phone or from a payphone. It was a different world back then compared to today.

What do you think the role of an artist is in this turbulent and unstable world? Of course, art can't solve the problems we have. You once said that your paintings, in some sense, are roadmaps that lead back into the mental state of individual consciousness. Perhaps this is the role of art today: to act as a roadmap for us, both physically and metaphysically, helping us find ourselves amidst these challenges.

When you look back, there have always been really bad moments – like the Vietnam War, the assassination of John F. Kennedy. But during those times, certain exciting things were happening. Like, the Beatles were playing when Kennedy died, and during the Vietnam War, Jimi Hendrix performed, as a protest, the national anthem at Woodstock.

Today, if you consider being a political artist, it might mean creating a state of mind where people can forget about the harsh realities around them. It's about encouraging them to focus on their own internal desires for how they wish the world could be and giving them a way to contemplate that ideal, rather than dwelling on how things actually are.

Today, if you consider being a political artist, it might mean creating a state of mind where people can forget about the harsh realities around them. It's about encouraging them to focus on their own internal desires for how they wish the world could be and giving them a way to contemplate that ideal, rather than dwelling on how things actually are.

George Condo, Hydra Mayor George Koukoudakis, Dakis Joannou. Photo: Arterritory.com

My last question is a bit funny, but I think it's quite serious as well. If an alien were to approach you because of your paintings and ask, "What are humans as creatures?", what would your answer be?

Good one! I would probably say that we are aliens as well. But we just come from a different planet.

Thank you!

Title image: © George Condo.