Manifesta 10. The Narrow Door

03/08/2014

My colleague Gleb Yershov finished his first article on the international art festival Manifesta 10 with some lamentation regarding the complete absence in the city of St Petersburg of information or publicity of any description dedicated to the world’s most prestigious forum of contemporary art. I can now attest personally to the fact that, half a month later, the city, including the metro, is awash with posters and billboards celebrating Manifesta. With their purist design (tiny words and numbers on yellow background), they are reminiscent of some kind of announcements by the revenue service or technical safety instructions. However, they do exist, and hopefully will last through the official closing day on 31 October 2014.

Unlike the Moscow International Biennale for Young Art, the events of Manifesta 10 in St Petersburg are not underpinned by a single clearly defined theme; rather, they are united by a shared trend of thought, a mood or a vibe of ideas, as yet undefined to the stage of a dogma or a cliché. The viewer is groping his way through clouds of emanations and radiations, intuitively setting his own route. The main part of the main programme comprises works by distinguished masters. A wise and much-experienced festival of young (by definition) art is akin to Michelangelo Antonioni’s ‘Beyond the Clouds’ (‘Al di là delle nuvole’) film. The current – tenth – Manifesta was likewise mounted by a much-experienced master, the curator Kasper König. He has described the main exhibition as ‘counter-cyclical’: rejecting both chronological and linear order and based on a conversation between various eras and traditions. All of these intuitive shout-outs across centuries call to mind the oeuvre of another master curator, Jean-Hubert Martin, who loves staging confrontations between objects from some of the greatest treasuries of civilisation and freshly-made works of art.

‘The Institute’ by Louise Bourgeois: a cage with mirrors containing a mock-up of the New York Institute of Fine Arts

The unfocused centre has activated peripheral energies. Where do the borders of said centre lie – now, that is a big question. Formally, everything collected at the General Staff Building and described by Gleb Yershov is the main project. Then again – some of the works at the Winter Palace, agents of intervention into respectable museum halls, also are part of the main project. Even the distant Razliv museum complex, the place where a certain V.I.Lenin was hiding in a shed from the persecution of the provisional government in 1917, is now home to a small part of the main project of Manifesta – to wit, the Shed Museum in which the mechanism of political memory regarding events from the Bolshevik and Soviet past undergoes deconstruction.

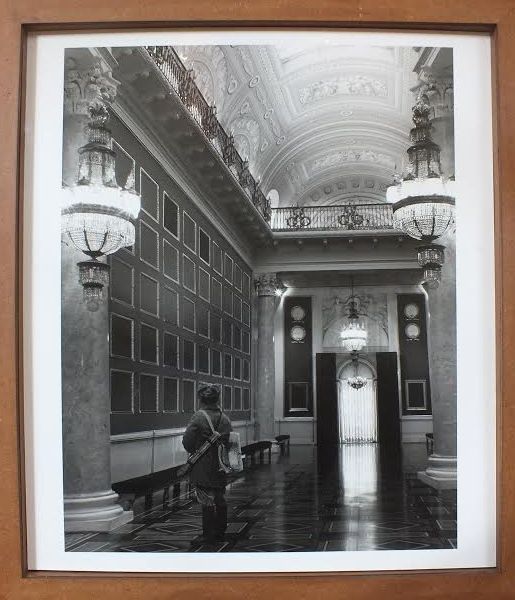

Theabundant nature of the main programmegives complete freedom when choosing the priorities of the festival and deciding which part of it is central and which – peripheral. From all of the things on view in the Winter Palace and the rest of the Hermitage buildings, what I liked most were the pieces where the site specific principle is applied wisely and sensitively. Among them, the one I rate the highest is ‘The Hermitage. 1941–2014’, a project by the Japanese artist Yasumasa Morimura, comprised of a number of stands placed throughout the museum. They feature photographic replicas of drawings by museum employees Vera Milyutina and Vasily Kuchumov made during World War II when the Hermitage had been evacuated. The huge halls with empty frames and museum attendants dressed in sheepskin coats are so much more impressive than Hirschhorn’s impressive ruins at the General Staff Building: the collapsed façade and exposed flat interiors where originals by Malevich, Filonov and Rosanova languish. Hirschhorn’sruin melancholy is all superficial; Morimura, on the other hand, has captured the moment of birth of the first shoots of conceptual art at the old museum. Let us turn to history. What Morimura did was essentially recreate the real display of empty frames that existed during the Siege of Leningrad. It was created by the then director of the Hermitage Museum Joseph Orbeli to ensure eventual efficient replacement of the evacuated paintings. The photographs of this display of empty frames create a striking impression with their phenomenal combination of the presented ‘text’ and the context produced by it. In this case, the text is the actual content of the photographs that we see: wartime reality, tragic in its forced anti-aestheticism. The paintings are gone, the frames are left behind, the museum is empty. And yet, even as the photographs point at the undisguised tragedy of the historical fact they have captured, they also make us contemplate other conceptual spaces. Basically, their message is about the difficult yet necessary task of linking together multiple worlds of knowledge about art – about the fact that empty frames – in the permanent exhibition of the museum, at that – become as significant as the traditional masterpieces normally displayed in them. There is evidence that one of the blockade winters saw the empty frames transform into the subject of an unusual tour. A museum guide before the war and the head of the museum security service during the Siege, Pavel Gubchevsky treated the soldiers who had helped clean the museum after an artillery attack to a tour of the Hermitage halls. There were stories of the paintings and there were the frames – but not what was supposed to be inside the frames.

A proof of the full-bloodied life of the museum in the consciousness of people loyal to it, the fact also speaks of the incredible significance of communicating with works of the free arts on a number of levels. Gubchevsky’s tour of the exhibition of empty frames was essentially the first conceptual action of contemporary art, albeit an uber-significant and super-serious one. Now, this is where language, word, text and commentary justified their presence in the world of art to the full! And Morimura remembered the fact and tied the threads of two different times tightly together.

Works by the Japanese artist Yasumasa Morimura deal with the life of the Hermitage halls during the Siege of Leningrad

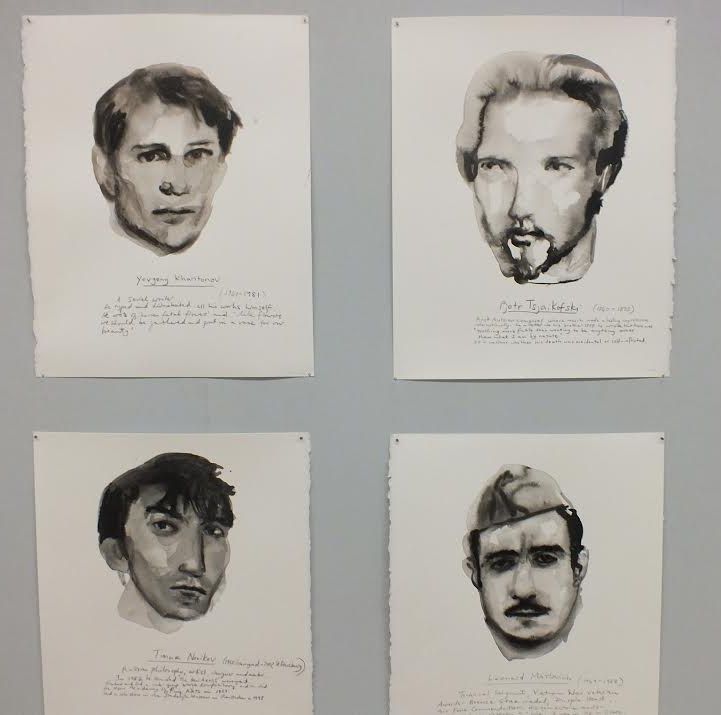

With the official Russian policy of discriminating and humiliating the minorities in mind, the ‘Great Men’ project by Marlene Dumas comes across as very topical and profoundly tender. It is a series of light, mostly watercolour,portraits of famous homosexual men who have contributed greatly to world culture, including Nureyev, Diaghilev, Tchaikovsky and Tennessee Williams. Airy, light and mobile, almost like patterns of reflected light on glass, the faces are nevertheless extremely memorable – not least due to the fact that the protective layer of official pretence has been peeled off from the features. They are now trusting and vulnerable and meet with lively response from the viewer (who is hopefully responsive and alive himself).

Marlene Dumas has immortalised a number of great Russian gays in a series of light portraits

Susan Philipsz’ sound-art installation is an excellent example of the architecture of sound.Tall and slender like note staves in a musical score, Corinthian columns line the Main Staircase of the New Hermitage, designed by the great Bavarian architect Leo von Klenze on commission from Nikolai I. In the space between the columns, acoustic pockets are formed, filled with sounds of piano music. The museum space has acquired a new dimension of visible sound. The piece stirs and inspires. Also, like all things of true genius, Philipsz’ work is simplicity itself.

It is exactly this sort of wise simplicity that makes the installation by Lara Favaretto, a young Italian artist and heiress to the ideas of arte povera, so convincing. Favaretto has brought a dozen or so crude concrete blocks to a hall housing antique sculptures. The contrast is very obvious but the very fact of this idiotic concrete rubbish transforming itself into something that also can carry some sort of light of the living creative thought remains intangible. It is born in the consciousness of each individual viewer.There certainly is trash so much worse than this that gives rise to verse without a tinge of shame. To see the ‘secrets of trade’ defined by the Russian poet Anna Akhmatova put to practice, you have to leave the Hermitage and head for the former Cadet Corps No. 1 on Vasilievsky Island. Its elongated time-worn rooms from various eras house yet another segment of Manifesta 10. And that’s a perfect opportunity to check out the ‘bright dandelions by a fence’, as well as ‘burdock and [..] cocklebur’ – not to mention ‘an angry shout, the bracing smell of tar’, ‘mysterious mildew on the wall’…

The entrance to Manifesta 10 at Cadet Corps

The Cadet Corps has been commandeered by Russian artists. One of the keynotes of the exhibition is the subject of a traumatised memory. In the formerly beautiful column hall, there is a half-human half-globe by Irina Korina on the floor. It has fallen to the ground through a polythene hole. The little smiley-face is wearing an expression of slightly stupid infantile submission. The globe has come rolling all the way from the officially optimistic 1960s. It is sporting a sign that says‘Eurasia’, which, of course, is the catchword of the official optimism of the twenty-teens.You feel like crying from pity for the tiny fragile world that, for the umpteenth time, has once again become a toy in the hands of callously ambitious politicians. In the hall that hosted the First Congress of Workers and Soldiers’ Deputies in 1917, Ivan Plyushch has hung a red carpet from the floor to the ledge, placing pieces of broken deputies’ chairs underneath it. Next door there are some overlapping sonic fields of different sound-art projects and frowning bed sheet faces flapping in the wind (a piece by the MishMash Group). A separate exhibition is dedicated to ruins of old buildings and flats in the city landscape (the ‘Sketches of Optimism’ project). This sort of ruin archaeology and relishing the disintegrating substance of Existence suit the City on the Neva down to the ground: so many of the local intellectuals deliberately prefer escapism and contemplation of time-worn surfaces to social engagement and taking an active stance.

The MishMash Group. ‘Until They Tell Us STOP’. Frowns of winds, choruses of ventilators and notes from popular opera arias

What they also love in this city is erecting monuments to their own art mythology, foregoing any attempt at a detached look at an art phenomenon. An extremely interesting show, ‘The Life of the Wonderful Monroe’ (part of the Manifesta 10 Parallel Programme at the New Museum), as well as the exhibition catalogue are both based on the principle of mythologizing certain art critique maxims. The curators Olesya Turkina and Victor Mazin have meticulously and brilliantly retold the postulates of the mythical science of ‘monrology’ made up in conjunction with the artist Vladislav Mamyshev-Monroe. What the product of their labour amounts to is a lengthy folkloric epic that keeps returning to its initial theses (reflection; binarity; system of signals), rolled into an opulently decorated vignetted scroll. The design of the catalogue with its big print and continuous text divided into chapters, its eye-catching pictures and Bilibin-style ornaments also bears a likeness to a fairytale book.The first big exhibition project dedicated to Mamyshev-Monroe has turned out very sincere, kind and, in some ways, also quite naïve – in fact, just like his art. We are now looking forward to the next attempt, hopefully using some clearly defined research impartiality to contemplate the intersection between the oeuvre of the wonderful Mamyshev-Monroe and art of certain affinity by other contemporary artists (not least by Cindy Sherman mentioned in the catalogue).

Aslan Gaisumov. ‘Elimination’

The Parallel Programme’s projects I found most convincing were all referring in one way or another to the subject of the birth of new aesthetics – the ones giving hope that the new world will be fully accepted after all while still remaining responsive to the old culture. In this context, I liked many of the projects at the START programme of young artists at Cadet Corps (works by Tatiana Akhmetgalieva, Kirill Makarov, Igor Samolyot, Taisia Krugovykh et al). Making a virtuoso connection between the old and the new, the paintings by Yegor Koshelev – hoping to be frescoes in some giant domed hall, and with good reason at that – part of the ‘Art of Translation’ programme, were impressive as well. The ‘Domestication’ photo installation by Olga Chernisheva was wonderful. I have to agree with the curator Yekaterina Andreyeva about the artist’s magical way of finding a new energy of life in the nondescript process of the construction of a new residential complex, instilling soul into the insipid mundaneness and transforming it. Just like Anna Akhmatova’s ‘Secrets of the Trade’ poem cycle.

In front of Sergei Prokofiev’s ‘Obstruction’

For some reason, the entrance to the Manifesta 10 exhibition at Cadet Corps No. 1 has stuck in my mind: two giant numbers and a very modest door that would not be out of place in an ordinary flat or class-room. The, as yet, very contemporary art is making itself at home in St Petersburg very cautiously; and you would not call its resonance in the public particularly strong. Still, the appearance of such a door to contemporary art, however narrow, is a joyful thing indeed.