“To be honest, I don’t want you to think that I am pretending”

27/07/2015

Vladislav Mamyshev-Monroe. “Archive M”

Moscow Museum of Modern Art

Through 23 August, 2015

I didn't love the death-hussars,

And not the howitzers with girls' names,

And at the end when the great days came,

I went discreetly away.

Hugo Ball

Let us imagine that we know nothing about Vlad Mamyshev-Monroe. We’ve never met this brilliant charlatan, never thoughtfully pondered the ancient nature travesty which in him found the embodiment of the ideal, never died of laughter watching his Stierlitz impersonation (a popular character in the Soviet book series written in the 1960, later adapted into film) never sang along with his languid Marilyn reenactment and effervescent rendering of “Volga-Volga”, never shied away from his materialized shadow of Hamlet's father, never lived through his sudden, tragic and grotesque death. Imagine we just came to visit the Moscow Museum of Modern Art, where his work takes up all the exhibition space, 27 rooms of the main building and also the outer building. Not distracted by memories of the fire, the adventures, the trashy moments and the frenzy that accompanied his short but stormy life, it is easier to see the point of his works. He was a shocking character of the art party, proudly bearing the gift of a name from a visiting celebrity as the “Russian drag queen”, he was a freak and a weirdo who appears to us as a marginal and hard-working artist with an enormous amount of artwork. If he were a freak, then he was one of those who hated the abridging of freedom of action and expression, in whom Frank Zappa saw direct followers of Dada art.

Photo: Orlan Duran

Elena Selina from XL Projects who was Mamyshev-Monroe’s friend and gallerist, and who is now one of the main organizers of the exhibition as she is the brain, the heart and the soul of this project, came together with Antonio Geusa (who is the primary expert on Russian video art) to gather the most complete set of works by Monroe to date, and to tell Monroe’s story of creativity and life in the most elaborate way step-by-step.

Final touches before the opening

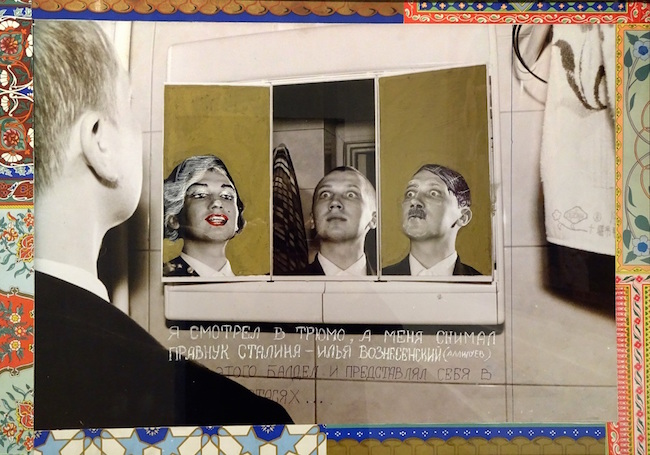

Fortunately, his grand entrance into the art scene took place during perestroika, otherwise it is difficult to imagine what would have been the fate of this special teenager who got expelled from school and from the Komsomol (youth organization in the Soviet Union) for showing interest in Adolf Hitler’s persona, the first of an endless series of characters that Monroe eventually tried on himself. Young Mamyshev drew not only on paper but also on his own face, and with an enthusiastic horror found similarities with the major villain of the 20th century. Soon after the “pole of Evil”, Mamyshev added the “pole of Good” by incorporating the image of Marilyn Monroe, who gave such an interest to the artist that it cost him an early discharge from army service (he served in the kids' club Baikonur Cosmodrome) with the diagnosis of mental illness.

Offended by the state institutions, Mamyshev returned to St. Petersburg, and took refuge under the wing of the “New Academy of Fine Arts”, underwent an elegant carving and gained a bright pseudonym, and his passion for dressing up in the intoxicated atmosphere of political and creative freedom transformed into his art of impersonation. In fact, here is where the real story of the performance artist begins, as he managed to collect a plethora of images between these two opposing poles, a dictator and an actress, which he called “the extremes that showed the face of humanity under the veil of existing civilization”. Among those there are historical characters and working politicians, literary heroes and pop celebrities, fantastical creatures and close friends. The walls of the main hall of the exhibition are densely covered in photographs documenting the diversity of these characters. There are two thousand of them, and there will be even more, as there is a special place left for newly discovered evidence which continues to arrive from the owners.

Although Vlad Monroe had a great love of a wonderfully beautiful life, he did not care much about his heritage, and therefore the curators had to make Herculean efforts to combine the exhibition of his works from public and private collections, from digital and paper archives which recently has been established in Moscow by the Mamyshev-Monroe Foundation, and a variety of artifacts deposited to colleagues and acquaintances. However, now the exposition, which was arranged diversely and capriciously, where traditionally decorated rooms neighbor theatrically decorated and lit ones, and strict showcases are replaced by stark installations, has everything: photo series, collages, albums, paintings, video, scratchings (photographs scratched with a scalpel), stained glass, and the main stages of life are filled with live testimonies.

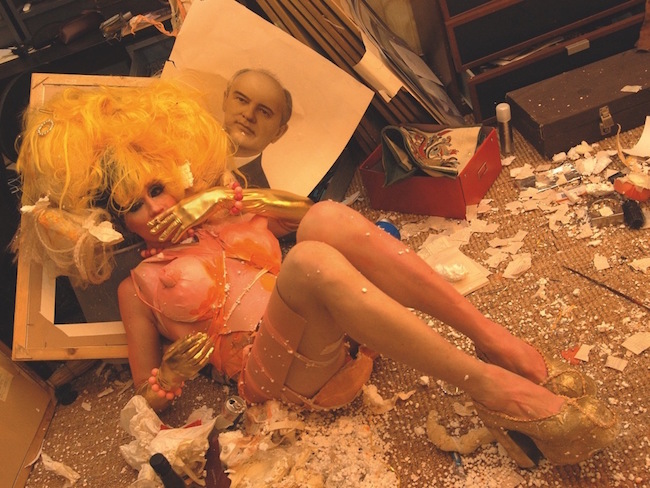

First there was St. Petersburg, with performances at Kuryokhin’s “Pop Mechanics” concerts, “Pirate TV” in the company of Timur Novikov, Georgy Guryanov and Juris Lesnik, the magazine “Kabinet” with Sergei Bugaev-Africa, Olesya Turkina and Victor Mazin. Later after soaking up the “Petersburg narcissism”, Monroe worked a lot in Moscow. On the channel REN-TV he did the “Pink Block” in Artemy Troitsky’s show “Signs of Life” and successfully cooperated with Elena Selina’s XL Gallery. The images multiply and swarm, reflecting the stream of the surrounding life. Large series appear, such as “Miserable Love”, “Life of Remarkable People”, “Russian Questions”, and, firstly only shown at this exhibition, “Barbie” and “Psycho”. And finally, the highest point of the official recognition of his lifetime was in 2007, when Monroe received the Kandinsky Prize in the category “Media Art. Project of the Year” for the film “Volga-Volga”, which was a sneering paraphrase of the Lyubov Orlova’s role in the film, another of his favorites.

From the series "Barbie". 2005. Courtesy: Archive of the Mamyshev-Monroe Foundation

But times are changing irreversibly. Only just recently Mamyshev was cheerfully decorating portraits of politicians with fake eyelashes, sequins and wigs, then suddenly the artist felt less and less comfortable when faced with reality. The first call sounded in 2003 at the exhibition “Caution, Religion”, which was defaced by Orthodox activists, and a collage by Monroe got hurt in the process. His easy and cheerful talent did not tolerate the artificial rules and boundaries. He signed more and more letters of protest and spent increasingly more time in Bali, planning his new projects there. In March 2013, during the exhibition “Polonium” at the Moscow Museum of Multimedia, came the news of his death, which initially many took as yet another trick by the artist. This time, however, everything was true, Vlad Monroe drowned in Bali in the hotel pool.

A good artist is a dead artist, and we can’t escape this principle. Last year, in the framework of the parallel program “Manifesta-10” art critics Olesya Turkin and Viktor Mazin already exhibited the first major posthumous retrospective of Monroe at the New Museum in St. Petersburg, presenting him as a “symbol of the post-perestroika era and a hero of this changing time”. Elena Selina greatly supplemented a catalogue of the artist’s little known and never gone public materials. The great thing was that she was able to show a live process of Monroe’s latest impersonation. Preparation sketches, texts, test shoots, costumes, jewelry, household items tell how exactly the artist would start from specific details, then spin the plot, surprisingly getting the accurate image and time. This wasn’t just brilliant natural histrionics celebrated by all those who knew him closely, but also close attention to the facts, a sort of stylistic perfection, and the creative courage - all there are present in his best works.

The saturation of the Moscow exhibition is breathtaking but it also starts to hurt the eye. In order to see everything that is presented to the spectators by the curators, you’d need an unusually large amount of time for a one-man retrospective. However, it gives a better understanding of the bright and free time we are unfortunately leaving behind. You can certainly speculate whether the ability to draw is necessarily an option for the modern artist, you can complain about the overly kitsch art salon of the “Scratchings”, you can find some faults in everything, but the important point will still not disappear, which is the fact that an artist with an ironic smirk passes through himself Others in order to come to terms with their personas.

From the series “Dostoyevsky in Baden-Baden”, 2004. Courtesy: Archive of the Mamyshev-Monroe Foundation

The passion for transformation and the use of their own bodies as objects of art have long been an obsession of artists. Without going too deep into history, remember Duchamp’s sweetest Rrose Selavy, or our contemporary, the English artist Grayson Perry, although most often Mamyshev-Monroe’s art is compared with the likes of the famous Cindy Sherman and Yasumasa Morimura. Regardless of these facts, the crowds of friends, colleagues and fans that filled the halls of the museum on the opening day, retained the strong belief that “Our Vlad is cooler!”