Enough as a Point for Beginning

28/11/2011

The new space for the Tallinn gallery Temnikova & Kasela—a cross between the last names of art dealer Olga Temnikova and her supporter Indrek Kasela—were unveiled with a co-exhibit of works by Latvian artist Inga Meldere (1979) and the German-born Finnish artist Mikko Hintz (1974), Enough is Enough. In the exhibit, a dialogue is created between two powerful artists, who until recently were bound only by painting, yet a meeting in real life served as a reason to begin a “conversation” in the gallery space. This, of course, is a challenge to both sides—both for Inga, who is still a relatively young artist (though in the Latvian art scene she has already earned lots of accolades) and for Mikko, who isn’t particularly well known in the Baltics, yet is an established artist in Finland. Also because both of their painting styles can be dubbed sensitive and nuanced, based on very fragile layers, autonomous and self-sufficient in the peripheries of their inner, creative spaces. In the exhibit format as it appears in the gallery Temnikova & Kasela, it is interesting to see how the equal mental worlds of both artists intertwine; different painting school traditions encounter one another, as does the desire to challenge them wherever doubts and quests appear.

Mikko’s paintings could be described as small-format layerings of chromatic fields. For example, a painting in red or a painting in black (Une and Fu), which the artists himself calls landscapes. Other works consists of different color combinations, which are clearly separated from one another and are precise in their fields (for example, Mal, Fune, Tavs). On an emotional level, these works call to mind vintage objects, particularly from the 1960s and 70s, with a design of clear and “polished” forms that, slightly tarnished and covered with the patina of time, once again regain their value. Though these are only the initial associations of feelings, Mikko’s exposition is the intermediary that reveals technical nuances which are culpable in this flow of associations. Pigments and acrylics on a surface primed with chalk were used to create the works. Layers of colors are placed atop one another, yet this is revealed not by the surface of the painting, looking at it frontally, but rather the edge of the sides, on which you find drops and drips of paint. These draw attention to the multiplicity of layers beneath the topmost, most visible layer.

The angle from the side is the main thing in perceiving these works, because it indicates that here you’ll find not some particularly notable aesthetic qualities in the surface or its finish, but rather a conceptual proposition. The beginning and end points are important for Mikko. As he himself reveals, a beginning is full of desires and illusions, put in motion by imagination; yet as you attempt to strives for these imagined “figures,” you usually suffer one defeat after another. Mikko talks about a “process full of confusion and dissatisfaction, which leads you to an impasse”[1]. The main idea, the artist says, is a union between the joyful and the shadowy side of things, or the presence of the nice and pleasant in the unpleasant.

[1] Iliana Veinberga, press release for the exhibit Enough is enough

A theme that Mikko has been working with for some time, and which is the main theme in this exist, is boredom. The artist refers to Martin Heidegger, who explains boredom as a sinking into the depths of existence, a becoming nothing. Boredom is the state in which we can begin to perceive Being. “When we are bored—really, really, really bored—we are no longer engaged with the ordinary, trivial, day-to-day things that occupy most of our time. When we are bored, ‘drifting hither and thither in the abysses of existence like a mute fog,’ all beings become a matter of indifference, undifferentiated from one another. Everything merges or dissolves into an un-distinguished unity.” [2] This state, Heidegger admits, leads us to fear and anxiety. In this fear we begin to feel that Being and Nothingness is one and the same thing.

It’s interesting that Mikko refers to Heidegger when reflecting upon the nature of painting, which certainly doesn’t have to be entertaining or surprising each time (though today’s environment demands this with its endless need for a “refresh”). In this context, the artist’s works seems to suck you into a feeling of boredom, which is not a negative expanse but, rather, a constant state of essence, of what is needed, in which a delving into and contemplation of the extant takes place.

One of the most direct, yet not the only, point of contact in Inga Meldere and Mikko Hintz’s works is the motif of the face. In Mikko’s paintings they are abstract; when they are combined, two half-circles form a certain type of facial fragment, which we imagine seeing perhaps from an unusual angle. It’s possible that the features of this gaze can be recalled from childhood, when we possessed the ability to perceive things fragmentally, instead of as a whole.

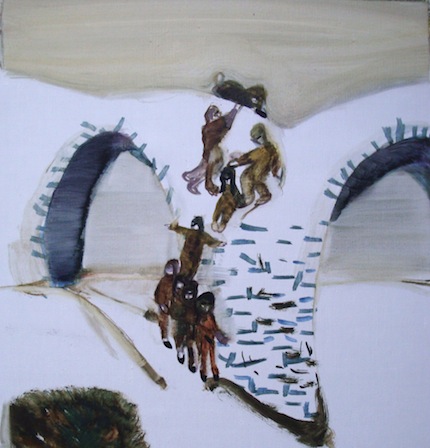

Faces, or more precisely their muting, is one of the most essential moments in Inga’s works. I know that many artists have asked why these faces are left “blank,” unspecific, like touched-up spaces, similar to photographs where an undesirable detail is covered up. If the motif of a human figure is present and to a certain extent tells a story, then the face always remains unknown, which makes the figures abstract, unspecific, and generalized. Therefore each viewer is able to identify with it or apply it to his sense and recognize it intuitively. The faces depicted by Mikko, unlike those portrayed by Inga, are not a reference to a feeling, emotion, or experience, but rather describe a certain type of viewpoint, which is also conceptually in tune with the nature of his paintings.

Knowing Inga Meldere’s work, I must say that this exhibit is a special event, because until now her works have never been displayed in tandem with another artist’s (not counting group exhibits). This format now offers a challenge not only for the artist herself, but also for the viewer, who can look at the paintings from a slightly different point of view, evaluate them, equate them, catch nuances that perhaps were muted in other solo shows and hidden beneath the aestheticizing of a convinced manner of painting.

At the exhibit, Inga’s paintings both provide an unexpected surprise (this applies most to the three works Incrimination of Truth, Pay for Attention, and The Logics of Result) and reveal the dynamics and features of her characteristic style. Speaking about the latter, I must emphasize that the artist’s creative direction has never stopped at one point, though a few of her exhibits display a sense of completion. Inga herself admits that lingering here didn’t seem interesting to her; therefore you can observe various stages—both those where the works in their completion form a closed circle and enhance one another in a combined whole; and those where you can see the artist pushing away from what she has already achieved and heading off in search of something new.

[2] Stephen Hicks, “Heidegger and Postmodernism” : read here.

This exhibit reveals two differing trends. One lingers in a manner of painting that reached maturity only recently, for example, in the solo exhibit Nobīde at the XO gallery, where, maintaining “the position of a discrete observer,”[3] the understanding of a man and woman, their roles and relationships, was approached and expounded upon, paying attention to “what is what,” “what it must be,” or “how we perceive it.” The other trend is new accents with a more expressed focus on a story, which offer a different manner of working with portrayal. This is a certain surprise, because after Inga’s last solo show in Riga it seemed as if she was turning in the direction of larger and larger abstractions and conditionality, distancing herself from an overly narrative layer and reducing the aesthetics of the painting’s aesthetic to a minimum. Yet here again we see a return to narrative.

As Inga herself says, the breaking point can be found in the painting Coming Soon, which depicts a vase, or a jug, with a face. The hands placed over it attest to tears or their approaching, an attempt to hold them back. At the same time, the existing or imagined floods of tears are the vase’s shadow. Of course, we don’t know what is being cried over, and if they are tears of joy or sorrow. Inga admits that in this new painting she feels “pure”—in the sense of colors, brushstrokes, sparseness, and other qualities.[4] This moment makes us wait impatiently for some further step in the artist’s activities, which, in her own words, possibly won’t be so soon and maybe once again will be exhibited only somewhere outside of Latvia.

Either way, the new works are just as “Meldere-like” as before: nuances in their games of colors, careful and fragile, provoking some flare-up or moment from the structures of characters and images that we save as files in the database of our memories.

I don’t know whether it is just my impression, yet it seems as if the trio of new paintings, which I mentioned before, possess that mode of understanding in which children depict the surrounding world, that is, transferring to a plane a possible activity with many small and unspecific figures, which are always found in an active process, trying to tell a definite story. Yet no matter how specific and understandable this story is to the person who depicted it, the story remains hidden to the viewer, offering just an intimation of its essence. The intrigue remains. And Inga successfully preserves it.

For Inga Meldere and Mikko Hintz, Enough is Enough is obviously a very careful step toward one another. Here you can sense both a respect for painting as such, which for both of them is the main form of expression, and a substantial amount of work and struggle with oneself, believing in an inner driving power and one’s own points of reference, without trusting much in external influences. I believe that, in the future, this collaboration will lead to many interesting twists and turns and discoveries for both artists, because here, though unconsciously and still unsurely, a valuable meeting has taken place.

[3] Iliana Veinberga, press release for Inga Meldere’s exhibit Nobīde, here

[4] From a private correspondence with Inga Meldere