Centrifugality as a Guarantee of Harmony

Review: The Bergen Assembly 2016

28/09/2016

There is a certain aura of mystification surrounding the history of the Assembly set in the incredibly beautiful Norwegian port city of Bergen. If we look at materials dating back three years, posted, for instance, on the Russian Colta culture portal, we learn that, apparently, the inaugural edition of the Bergen Assembly contemporary art forum took place in 2013 as a triennial, the brain-child of curators Ekaterina Degot from Russia and the American-born David Riff. Today, there is no mention of 2013 in the press releases on the 2016 Assembly, and the word ‘triennial’ is conspicuously absent from the available materials as well. We are told that the Bergen Assembly exists in the format of a conference since 2009. And, most intriguingly, the reason for convening it, the reason behind the summit within the assembly is identified as an attempt to understand what the format of biennial stands for today, subjecting it to critical analysis.

Effectively, it is the polemic on the format of the forum of contemporary art that is the structure-forming element here. It is like a centrifugal force enforcing the intention of the centripetal one. How extraordinary and paradoxical. The surprise here lies in the fact that this built-in contradiction postulated by the forum, this excess of multi-vector forces does not lead to destruction and collapse. What it does is create a complex space for reflection and a unique integrity of polemic.

In 2013, Ekaterina Degot and David Riff came up with the theme ‘Monday Begins on Saturday’, borrowed from the title of the famous Soviet-era novel by the sci-fi writers, the Strugatsky brothers. The first edition of the triennial was dedicated to a very complex and interesting idea, aiming to find out how viable today are the utopias of the ideal society ‒ to establish how susceptible they are to the bureaucratisation of consciousness exposed so brilliantly by the Strugatsky brothers in their novel. The exhibition was dispersed throughout the whole city of Bergen, hosted by a number of imaginary ‘institutes’ – a fact that may have underlined the curators’ fascination with the topical concept of ‘research’ while parodically annihilating the pretentiousness of the theme.

This year, there is no key theme, and the dynamics of the divergent vectors of the Assembly is more intensely evident. The polemic nature of the format is articulated as a method now. The festival is comprised of three platforms. The first one is named after its principal ideologist, the famous sound artist Tarek Atoui. The second one is FrEEthought, bearing the image of a complexly structured leftist philosophical summit dominated by the subject of Infrastructure. The third platform is Praxes. It is the one that is the least tolerant regarding the institutional format of biennials, triennials, etc. It is a sequence of free expressions by artists, performance artists and musicians, not embedded in the bureaucracy of various institutions.

All three parts of the Assembly complement each other perfectly well, helping comprehend the potential for prevailing over stereotypes, clichés, routine rules and regressive dogmas by the individual and the society alike.

End of Oil. Bergen Assembly 2016. A view of the installation. Photo: Thor Brødreskift

The leftist intellectuals’ Infrastructure programme has commandeered Bergen’s Gothic-style former fire station. At the Partisan Café, where the walls are lined with firemen’s ‘bunker gear’ and helmets, the ascetic interior hosts gatherings of publicists, journalists, artists and philosophers. They debate problems related to those defined by the series of exhibitions on view in the towers and passages of the fire station. For instance, one of them goes under the somewhat provocative title of 'End of Oil’. The curator Mao Mollona proposes a scenario of a hypothetical crisis of the oil industry, which plays a role of utmost importance in the Norwegian economy. One of the films depicts the final days of an unprofitable oil drilling station. Its workers have been made redundant. The film is a hyper-realistic portrayal of the life of various attributes ‒ everyday evidence of people being incorporated into an impeccably fine-tuned production cycle. A space lined with dressing-room lockers; canteen passages; cranes; hazmat suits... The body of this material evidence creates an illusion of a relentless uninterrupted chain of labour, life cycles, material benefits... And then comes the day when a memo is received: the station is being closed down. A drama of collapse ‒ but simultaneously a challenge: a recognition of the truth that, even at the best of times, we should never succumb to the hypnosis of stability; we should always stay flexible and farsighted when we are planning the life ahead of us ‒ of the truth, if you will, that nature (even more so if it is as fabulous as the Norwegian one) must not be used thoughtlessly, exploiting its resources. The solution comes when man is no longer greedy, opening up to the world. Only then the traumas of the oil crisis (increasingly obvious in Russia as well) will not be as unpredictable.

The leftist intellectuals’ Infrastructure programme has commandeered Bergen’s Gothic-style former fire station. Photo by Thor Brødreskift

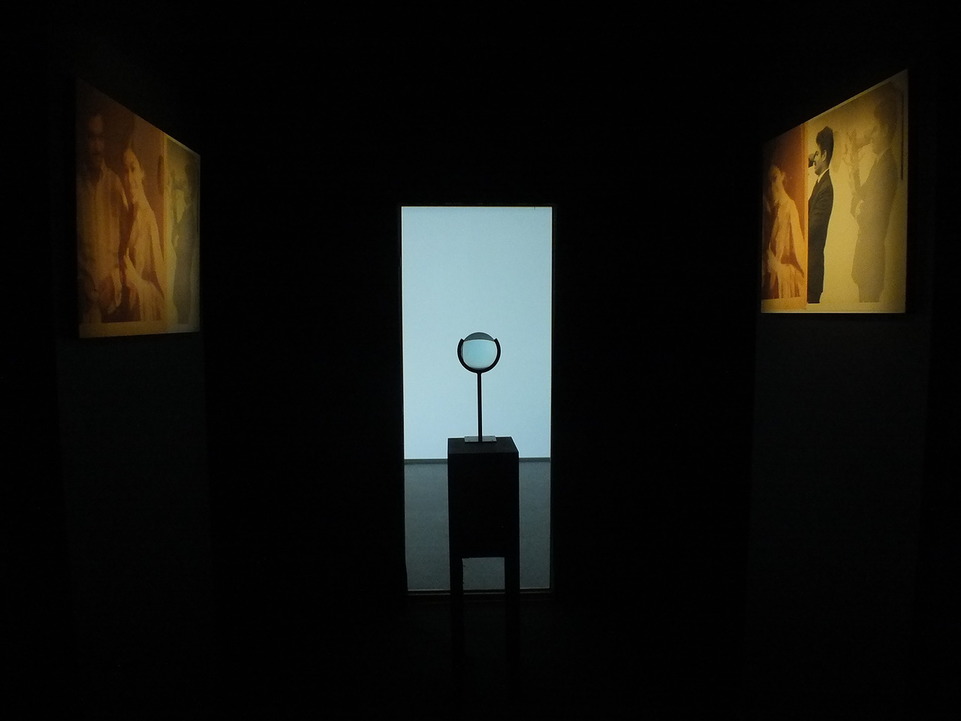

The other one of the frEEthought programmes is entitled ‘Shipping and the Shipped’. In the semi-darkness of the tiny office rooms of the old fire station, portraits of seafarers and freight forwarders communicate between themselves. They are reminiscent of photographs in family albums or adventure novels with ancient pictures. The video of port seascape is revealed to be turned upside down inside the big lens placed in front of the screen. I had the opportunity to speak with the curator of the programme, the economist and political scientist Stefano Harney. His study is centred around the problems of logistics (rational infrastructure of goods movement) in the capitalist world. The old photographs are a reference to the dawn of the capitalist era. According to Harney, it was in the 17th century that the system of logistics started to incorporate slave trade as an efficient economic principle.

To tell the truth, the project is focusing on logistics as a kind of fiction of the global capitalism. Based on a rational approach to labour and trade, commodity exchange and freight transportation, logistics involves nevertheless an inherent systemic error regarding the rights and freedoms of the individual, occupational safety, profit and efficiency. Therefore, logistics is perceived as something similar to a mythical werewolf or a mirage. Stefano Harney’s project captures these inherent logical glitches of logistics quite elegantly. The brainstorm atmosphere in the old fire station forces the viewer to adapt accordingly: to stay alert and employ their skills of critical analysis to full capacity. This is no place for relaxation and complacency.

Fragment of the ‘Shipping and the Shipped’ exhibition. Photo by

The Praxes platform is probably the one that is most vulnerable to criticism. The direction postulated as the central one in the performances, exhibitions and ‘spontaneous-creative-gesture’ type of films could be described as trash art: the cruder and more intolerant towards normative aesthetics, the better. Except for some reason, the reaction to the installations by artists like Lynda Benglis at the Bergen Kunsthall was mostly disappointment. The brutal style and slimy chaos of the fake materials, sadly, have lost all of their charm on the long road from post-war modernism and informalism. Today, as you look at some sort of amorphous gloopy heaps and shapeless bags, the image that appears in your mind is one of old people’s homes and infirmity. In the absence of a vivid artistic will (like the one present, for instance, in the works dealing with imitation materials by the Russian artist Irina Korina), you are left with the unpleasant feeling that you are simply being had – and some toothless mumbling is being sold as rebellious futuristic poetry.

Marvin Gaye Chetwynd. Bat Opera. 2014. Courtesy Massimo De Carlo, Milano/London/Hong Kong. Photo: Alessandro Zambinachi

The joyful world of gibberish and oddities created by the British artist Lali Chetwynd, currently appearing as Marvin Gaye Chetwynd, stands in striking contrast to this pretentious take on brutalism. She is, in some respects, a successor to the medieval street theatre, in others ‒ to the Fluxus performances and hippie happenings; in a way, it is also a continuation of the good old English nonsense rhymes and the tomfoolery of schoolchildren’s skit nights ‒ in any case, an altogether very cool and very funky experience. Made of plywood, cardboard and various other handy materials, her turtles, cats, toads, bats, chimeras and goblins create a sort of total theatre that will just suck you in, kicking and screaming ‒ even more so because the papier mâché masks are sported by Chetwynd’s thespian friends dressed up as fantasy characters. The carnivalesque hurly-burly and spontaneous mummery make Chetwynd’s programmes somewhat akin to the happenings by Andrei Bartenev, who frequently works in Norway and with whom the British artist, sadly, is not acquainted. A multi-level principle of dialogue is characteristic for both artists. Children and people looking for entertainment will simply have an excellent time at this funny carnival. Those in the know will understand and appreciate the subtle forays into the areas of social anthropology (Chetwynd holds a degree in anthropology), collective myths and taboos. Both Bartenev and Chetwynd can be considered real interveners ‒ saboteurs ‒ in the nomenclatorial world of the contemporary art institutions. They are brilliant at breaking conventions, making trouble and having a riot of a time. Chetwynd has populated the City Hall with throngs of bats of various colours and characters. Admittedly, what we are talking about here is a show of her paintings on view in the City Hall passages, all of them featuring bats ‒ scowling at us from all sorts of outlandish landscapes. It was nice to see that the artist’s brochure dedicated a whole page to the Russian semiotician Mikhail Bakhtin’s outstanding book on the medieval carnival and the upside-down world of parody.

The carnivalesque motley crowd of Chetwynd’s helpers. Photo by

Last but not least, the headliner of the festival ‒ the sound artist and expert of electroacoustic music Tarek Atoui. His WITHIN project seems to be an aggregate of every possible way of collaborating with the conventional systems of cultural interaction while simultaneously demonstrating the need to transcend conventions, to transgress boundaries and break down barriers. What is hearing outside the context of listening? How do the deaf understand music? Subjects like these have brought together whole institutions and consolidated teams of professional musicians and volunteers alike, including students of schools and institutes for hearing-impaired people.

Sound artist and expert of electroacoustic music Tarek Atoui. Photo by

All performances take place on the floor of an empty pool, a product of the 1960s communal architecture. The resemblance of a scientific laboratory instead of a concert is deliberately enhanced – even more so due to the fact that the adjacent space is housing artefacts that help make sense of the history of music without any music: ancient blueprints of siphon-like water devices; gloves for touching various surfaces; stroboscopes, etc.

Photo by

The collection of instruments for Atoui’s sound performances are simultaneously reminiscent of the noise-making devices used in the ancient theatre, a studio of electric musical instruments and a collection of various minerals, fabrics and samples of different species of trees. The percussion tables featuring various materials help feel the sounds in a tactile way. The Ouroboros creates sound before it has escaped the mouth of the performer. With the help of resonators and amplifiers, the vibrations of the larynx are transformed into an instrumental sound...

The pieces performed by chamber ensembles with appearances by Atoui contain references to the experiments with interpreting various musical texts by the noise orchestras of the Russian musician Peter Aidu ‒ who, incidentally, is also a frequent guest at Norwegian festivals.

Aidu, however, is better known for using an assemblage of hand-crafted instruments, without any electronic elements. The Russian noise orchestras value live sound above anything else. In the performances by Atoui, on the other hand, we witness the metamorphoses of sound as it moves through various media, from actual physical environment to a computer-generated one. In both cases, the resulting image is outstanding ‒ but very different. The noise exercises by Aidu & Co refer us to the Russian visceral mimetic tradition of world perception through arrangement of specific associative sequences, through landscapes, monumental scenes and classic catharsis. Programmes by Atoui & Co are often hard to listen to. The substance of the sound does not bother to be pleasing to the ear and does not promise to be recognisable through being rooted in any sort of tradition. The terms ‘informalism’ and ‘brutalism’ come to mind once again, as does the image of desperate wanderings through psychic landscapes by the abandoned human being, wrapped inside the cocoon of its own scream. Munch? Yes. Also, Jean Dubuffet with his rough folds of collective neuroses.

It came as a surprise then that the symphony, performed by an orchestra of hearing-impaired and deaf musicians, brought enlightenment. The music lived as a sense of the sacred in life, as blood pressure or the noise of the beating heart. The guest conductor both guided the orchestra and gave signs to assistants sitting in the audience and performing the role of sign language interpreters. A strange and beautiful friendship was born, based on care, mutual help and complete harmony. The knot of contradictions, so skilfully knitted by the ideology of the Assembly, was untangled – if only for a moment.